| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /məˈrɒpɪtænt/ mə-ROP-i-tant |

| Trade names | Cerenia, Prevomax, Vetemex |

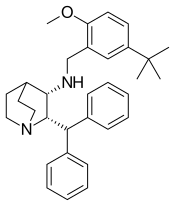

| Other names | (2S,3S)-2-Benzhydryl-N-(5-tert-butyl-2-methoxybenzyl) quinuclidin-3-amine, maropitant citrate (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, subcutaneous, Intravenous |

| Drug class | Antiemetic |

| ATCvet code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral: 20–30% dogs, 50% cats SQ: 90% (both) |

| Protein binding | 99.5% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP3A12 and CYP2D15) |

| Metabolites | CJ-18,518 |

| Elimination half-life | 6–8 hours (SQ) |

| Duration of action | 24 hours (SQ) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C32H40N2O |

| Molar mass | 468.685 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Maropitant (INN;[1] brand name: Cerenia, used as maropitant citrate (USAN), is a neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptor antagonist developed by Zoetis specifically for the treatment of motion sickness and vomiting in dogs. It was approved by the FDA in 2007, for use in dogs[2][3] and in 2012, for cats.[4]

Maropitant has mild pain-relieving, anti-anxiety and anti-inflammatory effects.

Veterinary uses

Injectable maropitant is used in dogs to treat and prevent acute vomiting; tablets are used for preventing vomiting from a variety of causes, though it requires a higher dose to prevent vomiting from motion sickness. The injectable version is also licensed for preventing and treating acute vomiting in cats.[5][3][6][7]

Maropitant is effective in treating vomiting from a variety of causes, including gastroenteritis, chemotherapy, and kidney failure;[8][9] when given beforehand, it can prevent vomiting caused by using an opioid as a premedication.[6][10] Some have claimed that maropitant is better at treating vomiting than nausea, pointing to cats with chronic kidney disease who, when receiving maropitant, had a reduction in vomiting but no corresponding increase in appetite.[4]

Maropitant has been used in acute cases of rapid or labored breathing to prevent vomiting that could lead to aspiration pneumonia.[11] It has been given in combination with a benzodiazepine to cats prior to stressful events (such as a veterinary visit) to possibly relieve hypersensitivity.[12]

When compared to other antiemetics, maropitant has similar or greater effectiveness to chlorpromazine and metoclopramide for centrally mediated vomiting induced by apomorphine or xylazine.[7] It works better than chlorpromazine and metoclopramide for vomiting peripherally induced induced with syrup of ipecac.[13] Unlike dimenhydrinate and acepromazine, which are used for motion sickness, maropitant does not cause sedation.[14]

Maropitant has been used as an adjunct treatment in severe bronchitis due to its weak anti-inflammatory effects.[11] It alleviates visceral pain and has been found to reduce the amount of general anesthesia (both sevoflurane and isoflurane) needed in some operations.[8][15]

Some believe that maropitant can be used in rabbits and guinea pigs to relieve pain caused by ileus (impaired bowel movements), though it lacks antiemetic effects in rabbits, who cannot vomit.[16]

Maropitant is given orally, subcutaneously, and intravenously.[3]

Contraindications

Maropitant is only indicated for dogs at least 16 weeks old, as some very young puppies suffered bone marrow hypoplasia (incomplete development ).[3] It should also not be used in animals with suspected GI obstruction or toxin ingestion.[9][14]

It is not recommended to give maropitant for more than five consecutive days, as it tends to accumulate in the body due to one of the liver enzymes responsible for its metabolism, CYP2D15, becoming saturated. However, there have been studies where beagles who were given maropitant for two weeks in a row showed no signs of toxicity.[14]

Because maropitant is metabolized by the liver, caution should be taken when giving it to dogs with liver dysfunction.[3][8] Caution should also be taken when giving it with other drugs that are also highly protein-bound, such as NSAIDs, anticonvulsants, and some behavior-modifying drugs;[3] such drugs compete with maropitant for binding to plasma proteins, increasing the concentration of unbound maropitant in the blood.[17] Maropitant should also not be used with calcium channel antagonists (used to treat high blood pressure) or in animals with heart disease, as it has a slight affinity for calcium and potassium channels.[18]

Side effects

Maropitant is safer than other antiemetics used in veterinary medicine, in part because of its high specificity for its target and thus not binding to other receptors in the central nervous system.[4] Side effects in dogs and cats include hypersalivation, diarrhea, loss of appetite, and vomiting.[8][12] Eight percent of dogs taking maropitant at doses meant to prevent motion sickness vomited right after, likely due to the local effects maropitant had on the gastrointestinal tract. Small amounts of food beforehand can prevent such post-administration vomiting.[7]

One of the most common side effects of subcutaneous administration is moderate to severe pain at the injection site.[6] Although the manufacturer recommends keeping maropitant at room temperature, many people have noted that keeping it in the fridge reduces the sting upon injection. Only unbound maropitant causes pain – it is normally formulated with beta-cyclodextrin to increase solubility; at cooler temperatures, more of the maropitant remains bound to the cyclodextrin, leaving less maropitant unbound.[10][16]

While there is no pain related to the intravenous administration of maropitant, pushing a dose in too quickly can temporarily reduce blood pressure.[6][14]

Fewer than 1 in 10,000 dogs and cats experience anaphylactic reactions.[18]

Overdose

Signs of maropitant overdose include lethargy, irregular or labored breathing, lack of muscle coordination, and tremors. Overdose of the oral formulation can cause salivation and nasal discharge, while overdose of intravenous maropitant can sometimes lead to reddish urine.[8] The LD50 is high, being over 2,000 mg/kg for oral maropitant in rats.[19]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Vomiting is caused when impulses from the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CRTZ) in the brain are sent to the vomiting center in the medulla. Motion sickness specifically occurs when signals to the CRTZ originate from the inner ear: motion is sensed by the fluid of the semicircular canals, which causes overstimulation. The signal travels to the brain's vestibular nuclei, then to the CRTZ, and finally to the vomiting center.[20]

Maropitant has a similar structure to substance P, the key neurotransmitter in causing vomiting, which allows it to act as an antagonist and bind to the substance P receptor neurokinin 1 (NK1).[3][21] It is highly selective for NK1 over NK2 and NK3.[6][16] Maropitant binds to the neurokinin receptors in the vagus nerves leaving the GI tract, as well as to receptors in the CRTZ and the vomiting center.[13][20] By virtue of working at the last step in triggering vomiting, it can prevent a broader range of stimuli than most antiemetics can.[21] It is effective against emetogens that act at the central nervous system (such as apomorphine in dogs and xylazine in cats), those that act in the periphery (e.g. syrup of ipecac),[10][14] and those that act in both (e.g. cisplatin).[7]

Pharmacokinetics

Maropitant's bioavailability is unaffected by the presence of food.[8] Bioavailability is 91% at the standard subcutaneous dose but 24% at the standard oral dose; the standard oral dose is higher to partially compensate for incomplete bioavailability.[3][14] It binds to plasma proteins at a rate of 99.5%; it has a low volume of distribution (9 L/kg) and is thus not extensively absorbed.[3][6] Subcutaneously administered maropitant had peak plasma concentration around half an hour after administration; the mean half-life is 6–8 hours, and a single dose lasts 24 hours in dogs.[6] Orally administered maropitant reached its peak plasma concentration within two hours.[8]

Maropitant undergoes 1st-pass metabolism by liver enzymes, mainly CYP2D15 (which has high affinity for maropitant and clears over 90% of it) but also by the lower-affinity CYP3A12.[7][8] Repeat dosing of maropitant eventually saturates CYP2D15, causing the drug to accumulate due to reduced clearance.[3] Thus, it is recommended to not use maropitant for more than five days straight, and to have a two-day rest period to allow maropitant to clear the body to prevent accumulation.[14][22] Maropitant has over 21 metabolites, though its major one (produced by hydroxylation) is CJ-18,518.[8]

Maropitant clearance is slower in cats.[14]

References

- ↑ "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN). Recommended International Nonproprietary Names: List 52" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2004. pp. 254–255. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Cerenia (maropitant citrate) Injectable Solution, Dogs" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Package Insert for Cerenia at Pfizer Animal Health (full detailed drug information)

- 1 2 3 Riviere JE, Papich MG (2017). "Maropitant". Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. John Wiley & Sons. p. 2828. ISBN 978-1-118-85588-1.

- ↑ "FDA Approves First Drug To Prevent and Treat Vomiting in Dogs". US Food & Drug Administration. 28 February 2007. Archived from the original on 2016-10-24. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 CVMP assessment report for Cerenia new route of administration (intravenous use) for the solution for injection (PDF) (Report). European Medicines Agency. 10 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Maddison JE, Page SW, Church D (2008). "Chapter 19: Gastrointestinal Drugs". Small Animal Clinical Pharmacology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 474. ISBN 978-0-7020-2858-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Plumb DC (2011). "Maropitant Citrate". Plumb's Veterinary Drug Handbook (7th ed.). Stockholm, Wis.; Ames, Iowa: Wiley. pp. 624–626. ISBN 978-0-470-95964-0.

- 1 2 Cote E (2010). Clinical Veterinary Advisor - E-Book: Dogs and Cats. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 33, 189, 208, 304, 444. ISBN 978-0-323-06876-5.

- 1 2 3 Pang SJ (2015). "Anesthetic and Analgesic Adjunctive Drugs". In Grimm KA, Lamont LA, Tranquilli WJ, Greene SA, Robertson S (eds.). Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia: The Fifth Edition of Lumb and Jones. John Wiley & Sons. p. 248. doi:10.1002/9781119421375.ch13. ISBN 978-1-118-52620-0.

- 1 2 Tamborini A (November 2016). "Maropitant & Canine Chronic Bronchitis" (PDF). Clinician's Brief. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- 1 2 DePorter T, Landsberg GM, Horwitz D (2015). "Tools of the trade: psychopharmacology and nutrition.". In Rodan I, Heath S (eds.). Feline Behavioral Health and Welfare - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-4557-7402-9.

- 1 2 Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC (2009). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine - eBook. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 200, 1513. ISBN 978-1-4377-0282-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Trepanier LA (February 2015). "Maropitant: Novel Antiemetic" (PDF). Clinician's Brief. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ↑ Swallow A, Rioja E, Elmer T, Dugdale A (July 2017). "The effect of maropitant on intraoperative isoflurane requirements and postoperative nausea and vomiting in dogs: a randomized clinical trial". Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 44 (4): 785–793. doi:10.1016/j.vaa.2016.10.006. PMID 28844293.

- 1 2 3 Le K (1 October 2017). "Maropitant". Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine. 26 (4): 305–309. doi:10.1053/j.jepm.2017.08.007. ISSN 1557-5063.

- ↑ Rang HP, Dale MM, Ritter JM, Flower RJ, Henderson G (2016). Rang & Dale's Pharmacology (8th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-7020-5362-7. OCLC 903234097.

- 1 2 "Contra-indications, warnings, etc". NOAH Compendium. National Office of Animal Health. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ Bahri L (September 2009). "Maropitant: A novel treatment for acute vomiting in dogs". dvm360.com. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- 1 2 Graham H (June 2013). "Motion Sickness in Small Animals: Pathophysiology & Treatment". Clinician's Brief. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- 1 2 Bahri L (1 September 2009). "Maropitant's pharmacokinetics and pharmacology". dvm360.com. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ↑ Nelson RW, Couto CG (2014). Small Animal Internal Medicine - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 418. ISBN 978-0-323-24300-1.