| Mauisaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Replica of paddle bones, Auckland War Memorial Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Family: | †Elasmosauridae |

| Genus: | †Mauisaurus Hector, 1874 |

| Species: | †M. haasti |

| Binomial name | |

| †Mauisaurus haasti Hector, 1874 | |

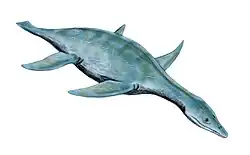

Mauisaurus ("Māui lizard") is a dubious genus of plesiosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period in what is now New Zealand. Numerous specimens have been attributed to this genus in the past, but a 2017 paper restricts Mauisaurus to the lectotype and declares it a nomen dubium.[1]

History of discovery

Mauisaurus remains have all been found in New Zealand's South Island, in Canterbury. Mauisaurus haasti was described by Hector in 1874 based on eight specimens and diagnosed by its cervical vertebrae and a humerus with large tuberosities. However, of these eight specimens, two, consisting of ribs and paddle, were lost, while another, the cast of a jaw fragment (the original fossil of which was also lost) was found to be a mosasaur. The most substantial specimen, 8a (DM R1529), consisted of fragmentary pubes, a partial ilium and hindlimbs, originally misidentified as part of the pectoral girdle.[1]

Mauisaurus gets its name from the New Zealand Māori mythological demigod, Māui. Māui is said to have pulled New Zealand up from the seabed using a fish hook, thus creating the country. Thus, Mauisaurus means "Māui lizard". Mauisaurus gets its scientific last name from its original finder, Julius von Haast, who found the first Mauisaurus fossil in 1870 around Gore Bay, New Zealand. The specimen was then first described in 1874.[2]

A second species was also named by Hector, Mauisaurus brachiolatus, based on the proximal end of a very large humerus as well as a humerus together with radius and radiale. There was some confusion regarding this species, as the description named it M. latibrachialis, while the specimen list included it under the name M. brachiolatus.

In 1962 specimen 8a was declared the lectotype of Mauisaurus haasti by Welles who further suggested that M. brachiolatus should be deemed a nomen vanum in an overview of Cretaceous plesiosaurs.[3] Later in 1971 Welles & Gregg revised the diagnosis of M. haasti and produced a detailed description of the lectotype, assigned Hector's specimen 8g as the paralectotype and rejected the remaining 3 specimen of Hector's original 8 as non-diagnostic, while themselves referring 9 new specimens (including both "M. brachiolatus" specimens) to the species.[4]

Mauisaurus was examined once more in 2005 by Hiller et al., rejecting the inclusion of the former "M. brachiolatus" material as well as several of the specimens referred to Mauisaurus in 1971, deeming all of them undiagnostic. In the same paper two more specimens are instead referred to the genus.[5] One of these specimens, CM Zfr 115, consisted of skull bones, a nearly complete series of vertebrae and bones from all four limbs. The animal was considered to be over 8 m (26 ft) in length.[5] A variety of other specimens were also referred to either Mauisaurus sp. or cf. Mauisaurus sp. during the early to late 2000s.[6][7][8][9]

It was later concluded that a hemispherical femoral capitulum, the defining apomorphy of Mauisaurus was also present in members of the Aristonectinae, which referred specimen CM Zfr 115 with its more than 60 neck vertebrae did not belong to.[1] This , together with additional information from Aristonectes quiriquinensis and Kaiwhekea katiki, was discussed in detail by Otero et al. in 2015.[10] The presence of femora with strongly hemispherical capitula in more than one aristonectine and also in non-aristonectine elasmosaurids brings Mauisaurus once again into question, with material previously referred to it now being placed in separate clades. Other anatomical features of Mauisaurus were also found amongst both aristonectines and non-aristonectine elasmosaurs, excluding them from being able to be used as apomorphies. More refined biostrategraphy furthermore questions the referral of many specimen, as the analysis showed that the various fossils attributed to this genus range from the middle Campanian to the early Cretaceous, a timespan of 10 million years (longer when taking into account referred specimens from Antarctica and South America). This longevity of a single genus is deemed unusually long by Hiller et al..[1] The paper concludes that the hypodigm of Mauisaurus consists of more than one taxon, with Mauisaurus only significant apomorphy being present in a variety of genera from different clades, rendering it non-diagnostic. While DM R1529 remains the lectotype, the genus must be treated as a nomen dubium and should instead be referred to as Elasmosauridae indet.[1]

Description

Little can be said about the appearance of Mauisaurus as the only known material is an undiagnostic, fragmentary pelvic area and flippers. The lectotype material shows some features that may indicate aristonectine affinities, but simultaneously possesses anatomical features more consistent with non-aristonectine elasmosaurs.

Cultural significance

Mauisaurus is one of the few New Zealand prehistoric creatures, and so, has had much publicity in the country. On 1 October 1993, a set of stamps was released to the general public. Although it depicted many other dinosaurs and prehistoric life, Mauisaurus was featured hunting fish on the $1.20 stamp.[11]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hiller, Norton; O’Gorman, José P.; Otero, Rodrigo A.; Mannering, Al A. (2017). "A reappraisal of the Late Cretaceous Weddellian plesiosaur genus Mauisaurus Hector, 1874". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 60 (2): 112–128. doi:10.1080/00288306.2017.1281317. S2CID 132037930.

- ↑ Gill, B.J.; Eagle, M.K. (2014). "New Zealand Mesozoic marine reptiles in the Auckland Museum collection". Records of the Auckland Museum. 49: 21–28. ISSN 1174-9202.

- ↑ Welles, S. P. (1962). "A new species of elasmosaur from the Aptian of Colombia and a review of the Cretaceous plesiosaurs". Geological Sciences. 44: 1–69.

- ↑ Welles, S. P.; Gregg, D.R. (1971). "Late Cretaceous marine reptiles of New Zealand". Records of the Canterbury Museum. 9: 1–111.

- 1 2 Hiller, N.; Mannering, A.A.; Jones, C.M.; Cruickshank, A.R.I. (2005). "The nature of Mauisaurus haasti Hector, 1874 (Reptilia: Plesiosauria)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (3): 588–601. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0588:TNOMHH]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 130607702.

- ↑ Fostowicz-Frelik, L.; Gaździcki, A. (2001). "Anatomy and histology of plesiosaur bones from the Late Cretaceous of Seymour Island, Antarctic Peninsula". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 60: 7–32.

- ↑ Gasparini, Z.; Salgado, L.; Casadio, S. (2003). "Maastrichtian plesiosaurs from northern Patagonia". Cretaceous Research. 24 (2): 157–170. doi:10.1016/S0195-6671(03)00036-3.

- ↑ Martin, J. E.; Sawyer, J.F.; Reguero, M.; Case, J.A. (2007). "Occurrence of a young elasmosaurid plesiosaur skeleton from the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of Antarctica: A Keystone in a Changing World". U.S. Geological Survey and the National Academies Open-File Report 2007–1047: 1–4. doi:10.3133/of2007-1047.srp066 (inactive 1 August 2023).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - ↑ Otero, R. A.; Soto-Acuña, S.; Rubilar-Rogers, D. (2010). "Presence of the elasmosaurid plesiosaur Mauisaurus in the Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) of central Chile". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 55: 361–364. doi:10.4202/app.2009.0065. S2CID 55767360.

- ↑ Otero, R. A.; O’Gorman, J.P.; Hiller, N. (2015). "Reassessment of the late Maastrichtian specimens from central Chile referred to the genus Mauisaurus Hector, 1874 (Plesiosauroidea, Elasmosauridae) with comments about the hemispherical femoral head among aristonectines". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 58: 252–261. doi:10.1080/00288306.2015.1037775. hdl:11336/53493. S2CID 129018714.

- ↑ "Dinosaurs". New Zealand Post Stamps. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

.png.webp)