| Abbreviation | MUTA |

|---|---|

| Formation | 9 October 1827 |

| Dissolved | 1837 |

| Type | NGO |

| Legal status | Disbanded in 1837 |

| Purpose | Representing workers as a class, not by craft. Advocacy for ten-hour day; engaging in political activism and workers' education. |

| Headquarters | Pennsylvania |

| Location |

|

| Coordinates | 39°56.912′N 75°8.727′W / 39.948533°N 75.145450°W |

Region served | Pennsylvania |

Official language | English |

| Affiliations | United Crafts |

The Mechanics' Union of Trade Associations (also known as The Mechanics' Union or MUTA) was an American trade union founded in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1827.[1]

Origin

During the winter of 1826–1827, more than 800 Philadelphians were jailed in a debtors' prison as a consequence of not having paid off their loans.[2]

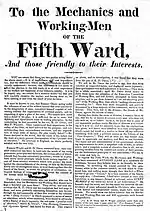

One anonymous prisoner working from his prison cell wrote an open letter, "To the Mechanics and Working-Men of the Fifth Ward, and those friendly to their Interests," describing the difficult work conditions suffered by working-class Philadelphians. The letter inspired a few outspoken writers to publish a widely circulated article demanding the workday be cut from twelve hours to ten hours. In June 1827, carpenters in Philadelphia struck for a 10-hour workday, agreeing to no reduction in wages. According to ExplorePAhistory.com:

"When [the carpenters] stopped working, housing and business construction nearly halted. By August, bricklayers, painters, typographers, glaziers, and craftsmen in other trades had walked off their jobs or threatened to do so."[2]

By October, the protesters had established the Mechanics' Union of Trade Associations, the first trade union to cross craft lines.

Activities

Almost immediately, the organization set up its own advocacy newspaper, the Mechanics Free Press, and began providing benefits for its members and political candidates, "who will support the interest of the working classes." The Mechanics' Union of Trade Associations became a proxy of the united crafts in Philadelphia, independent of the increasingly popular Jacksonian Democrats. Members of the association became known as "workies", and ran numerous candidates for local offices while forging coalitions with other Anti-Jacksonian organizations who supported educational reforms and economic regulations favorable to Philadelphia's workers.[3]

In 1837, ten years after the original carpenter protests, dozens of industries achieved their greatest victory when the City of Philadelphia passed legislation prohibiting businesses from employing workers for more than 10 hours a day.

Loss of influence

The gains of the organization, however, were relatively short lived. Soon after the 10-hour workday legislation, the Panic of 1837 caused many businesses to declare bankruptcy, and the subsequent rise in unemployment effectively deactivated the Mechanics' Union.

Legacy

Despite the relatively short lifespan of the Mechanics' Union of Trade Associations, future union leaders such as John Siney and William Sylvis looked to the Mechanics' Union for inspiration in the coal miners organizing movement. The organization also heavily influenced the idea of collective bargaining in the United States.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Staff, Bookrags (14 December 2010). "Mechanics' Union of Trade Associations Summary". bookrags.com. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- 1 2 Pennsylvania, History (20 October 2010). "Mechanics' Union of Trade Associations Marker". explorePAhistory.com. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ Pfingsten, Bill (25 July 2008). "Mechanics' Union of Trade Associations". hmdb.org. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

Further reading

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Volume 1: From Colonial Times to the Founding of the American Federation of Labor. New York: International Publishers, 1947.

- Helen L. Sumner, "Citizenship (1827-1833), in John R. Commons, et al., History of Labour in the United States: Volume 1. New York: Macmillan, 1918; pp. 167–332.