| Pyramid of Menkaure | |

|---|---|

| |

| Menkaure | |

| Coordinates | 29°58′21″N 31°07′42″E / 29.97250°N 31.12833°E |

| Ancient name | |

| Constructed | c. 2510 BC (4th dynasty) |

| Type | True Pyramid |

| Material | limestone, core red granite, white limestone, casing |

| Height | 65 metres (213 ft) or 125 cubits (original) |

| Base | 102.2 by 104.6 metres (335 ft × 343 ft) or 200 cubits (original) |

| Volume | 235,183 cubic metres (8,305,409 cu ft) |

| Slope | 51°20'25'' |

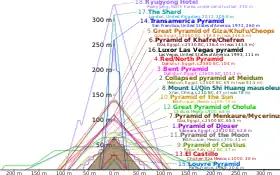

The pyramid of Menkaure is the smallest of the three main pyramids of the Giza pyramid complex, located on the Giza Plateau in the southwestern outskirts of Cairo, Egypt. It is thought to have been built to serve as the tomb of the Fourth Dynasty Egyptian Pharaoh Menkaure.

Size and construction

Menkaure's pyramid had an original height of 65.5 meters (215 ft), and was the smallest of the three major pyramids at the Giza Necropolis. It now stands at 61 m (200 ft) tall with a base of 108.5 m (356 ft). Its angle of incline is approximately 51°20′25″. It was constructed of limestone and Aswan granite. The first sixteen courses of the exterior were made of the red granite. The upper portion was cased in the normal manner with Tura limestone. Part of the granite was left in the rough. Incomplete projects such as this pyramid help archaeologists understand the methods used to build pyramids and temples.

Age and location

The pyramid's date of construction is unknown, because Menkaure's reign has not been accurately defined, but it was probably completed in the 26th century BC. It is a few hundred meters southwest of its larger neighbors, the pyramid of Khafre and the Great Pyramid of Khufu in the Giza necropolis.

Sarcophagus and coffin

Howard Vyse discovered on 28 July 1837, in the upper antechamber, the remains of a wooden anthropoid coffin inscribed with Menkaure's name and containing human bones. This is now considered to be a substitute coffin from the Saite period. Radiocarbon dating on the bones determined them to be less than 2,000 years old, suggesting either an all-too-common bungled handling of remains from another site or access to the pyramid during Roman times. The lid from the anthropoid coffin mentioned above was transported to England and may be seen today at the British Museum.[3]

Deeper into the pyramid, Vyse came upon a basalt sarcophagus, described as beautiful black and rich in detail with a bold projecting cornice, which contained the bones of a young woman. Unfortunately, this sarcophagus now lies at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, having sunk on 13 October 1838, with the ship Beatrice, as she made her way between Malta and Cartagena, on the way to Great Britain.[3]

Pyramid complex

Pyramid temple

In the mortuary temple the foundations and the inner core were made of limestone. The floors were begun with granite and granite facings were added to some of the walls. The foundations of the valley temple were made of stone but both temples were finished with crude bricks. Reisner estimated that some of the blocks of local stone in the walls of the mortuary temple weighed as much as 220 tons, while the heaviest granite ashlars imported from Aswan weighed more than 30 tons. It is assumed that Menkaure's successor Shepseskaf completed the temple construction. An inscription was found in the mortuary temple that said he "made it (the temple) as his monument for his father, the king of upper and lower Egypt."

Subsequent architectural additions and two stelae from the Sixth Dynasty suggest that a cult for the Pharaoh was maintained (or was periodically renewed) for two centuries after his death.[4]

Valley temple

The Menkaure Valley temple was excavated between 1908 and 1910 by American archaeologist George Andrew Reisner.[4] He found a large number of statues mostly of Menkaure alone and as a member of a group. These were all carved in the naturalistic style of the Old Kingdom with a high degree of detail.[5]

Queens' pyramids

South of the pyramid of Menkaure are three smaller pyramids, designated G3-a, G3-b, and G3-c, each accompanied by a temple and substructure. The easternmost is the largest and a true pyramid. Its casing is partly of granite, like the main pyramid, and is believed to have been completed due to the limestone pyramidion found close by.[6] Neither of the other two progressed beyond the construction of the inner core.[5]

Reisner speculated that the structures were likely tombs for the queens of Menkaure, and that the individuals buried there may have also been his half-sisters.[7] The archaeologist Mark Lehner argues that pyramid G3-a has a layout akin to a ka pyramid, which would have housed a statue of the king rather than a body. The fact that the structure once contained a pink granite sarcophagus,[8] however, has led scholars to speculate that it may have been reused as a queen's burial tomb, or that it served as a chapel where the body of Menkaure was mummified.[9]

Attempted demolition

In AD 1196, Al-Aziz Uthman, Saladin's son and the Sultan of Egypt, attempted to demolish the pyramids, starting with that of Menkaure. Workmen recruited to demolish the pyramid stayed at their job for eight months, but found it almost as expensive to destroy as to build. They could only remove one or two stones each day. Some used wedges and levers to move the stones, while others used ropes to pull them down. When a stone fell, it would bury itself in the sand, requiring extraordinary efforts to free it. Wedges were used to split the stones into several pieces, and a cart was used to carry it to the foot of the escarpment, where it was left. Despite their efforts, workmen were only able to damage the pyramid to the extent of leaving a large vertical gash at its northern face.[10][11]

See also

References

- ↑ Verner 2001, p. 242.

- ↑ Lehner, Mark (2001). The Complete Pyramids: Solving the Ancient Mysteries. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 221. ISBN 0-500-05084-8.

- 1 2 Hawass, Zahi. "The Pyramids at Giza: Khafre and Menkaure". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- 1 2 Lehner, Mark in: Manuelian, Peter Der; Schneider, Thomas (30 October 2015). Towards a New History for the Egyptian Old Kingdom: Perspectives on the Pyramid Age. ISBN 9789004301894.

- 1 2 Edwards, I. E. S.: The Pyramids of Egypt 1986/1947 pp. 147–163

- ↑ Janosi, Peter. "Das Pyramidion der Pyramide G III-a" (PDF).

- ↑ Reisner, George Andrew (1942). A History of the Giza Necropolis. Vol. III. Harvard University. pp. 186–187. (Note: This is the second unpublished follow-up to Reisner's work A History of the Giza Necropolis Vol. I, published by Harvard University Press)

- ↑ Verner, Miroslav (2007). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. New York City, NY: Grove Atlantic. p. 252. ISBN 9780802198631.

- ↑ Lehner, Mark (1997). The Complete Pyramids: Solving the Ancient Mysteries. London, UK: Thames & Hudson. pp. 134, 136. ISBN 9780500050842.

- ↑ Stewert, Desmond and editors of the Newsweek Book Division "The Pyramids and Sphinx" 1971 p. 101

- ↑ Lehner, Mark The Complete Pyramids, London: Thames and Hudson (1997) p. 41 ISBN 0-500-05084-8.

Further reading

- Verner, Miroslav (2001). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1703-8.

External links