Deities in ancient Mesopotamia were almost exclusively anthropomorphic.[2] They were thought to possess extraordinary powers[2] and were often envisioned as being of tremendous physical size.[2] The deities typically wore melam, an ambiguous substance which "covered them in terrifying splendor"[3] and which could also be worn by heroes, kings, giants, and even demons.[4] The effect that seeing a deity's melam has on a human is described as ni, a word for the "physical creeping of the flesh".[5] Both the Sumerian and Akkadian languages contain many words to express the sensation of ni,[4] including the word puluhtu, meaning "fear".[5] Deities were almost always depicted wearing horned caps,[6][7] consisting of up to seven superimposed pairs of ox-horns.[8] They were also sometimes depicted wearing clothes with elaborate decorative gold and silver ornaments sewn into them.[7]

The ancient Mesopotamians believed that their deities lived in Heaven,[9] but that a god's statue was a physical embodiment of the god himself.[9][10] As such, cult statues were given constant care and attention[11][9] and a set of priests were assigned to tend to them.[12] These priests would clothe the statues[10] and place feasts before them so they could "eat".[11][9] A deity's temple was believed to be that deity's literal place of residence.[13] The gods had boats, full-sized barges which were normally stored inside their temples[14] and were used to transport their cult statues along waterways during various religious festivals.[14] The gods also had chariots, which were used for transporting their cult statues by land.[15] Sometimes a deity's cult statue would be transported to the location of a battle so that the deity could watch the battle unfold.[15] The major deities of the Mesopotamian pantheon were believed to participate in the "assembly of the gods",[6] through which the gods made all of their decisions.[6] This assembly was seen as a divine counterpart to the semi-democratic legislative system that existed during the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 BC – c. 2004 BC).[6]

The Mesopotamian pantheon evolved greatly over the course of its history.[16] In general, the history of Mesopotamian religion can be divided into four phases.[16] During the first phase, starting in the fourth millennium BC, deities' domains mainly focused on basic needs for human survival.[17] During the second phase, which occurred in the third millennium BC, the divine hierarchy became more structured[17] and deified kings began to enter the pantheon.[17] During the third phase, in the second millennium BC, the gods worshipped by an individual person and gods associated with the commoners became more prevalent.[17] During the fourth and final phase, in the first millennium BC, the gods became closely associated with specific human empires and rulers.[18] The names of over 3,000 Mesopotamian deities have been recovered from cuneiform texts.[19][16] Many of these are from lengthy lists of deities compiled by ancient Mesopotamian scribes.[19][20] The longest of these lists is a text entitled An = Anum, a Babylonian scholarly work listing the names of over 2,000 deities.[19][17] While sometimes mistakenly regarded simply as a list of Sumerian gods with their Akkadian equivalents,[21] it was meant to provide information about the relations between individual gods, as well as short explanations of functions fulfilled by them.[21] In addition to spouses and children of gods, it also listed their servants.[22]

Various terms were employed to describe groups of deities. The collective term Anunnaki is first attested during the reign of Gudea (c. 2144 – 2124 BC) and the Third Dynasty of Ur.[23][24] This term usually referred to the major deities of heaven and earth,[25] endowed with immense powers,[26][23] who were believed to "decree the fates of mankind".[24] Gudea described them as "Lamma (tutelary deities) of all the countries."[25] While it is common in modern literature to assume that in some contexts the term was instead applied to chthonic Underworld deities,[26] this view is regarded as unsubstantiated by assyriologist Dina Katz, who points out that it relies entirely on the myth of Inanna's Descent, which doesn't necessarily contradict the conventional definition of Anunnaki and doesn't explicitly identify them as gods of the Underworld.[27] Unambiguous references to Anunnaki as chthonic come from Hurrian (rather than Mesopotamian) sources, in which the term was applied to a class of distinct, Hurrian, gods instead.[28] Anunnaki are chiefly mentioned in literary texts[24] and very little evidence to support the existence of any distinct cult of them has yet been unearthed[29][24] due to the fact that each deity which could be regarded as a member of the Anunnaki had his or her own individual cult, separate from the others.[23] Similarly, no representations of the Anunnaki as a distinct group have yet been discovered,[23] although a few depictions of its frequent individual members have been identified.[23] Another similar collective term for deities was Igigi, first attested from the Old Babylonian Period (c. 1830 BC – c. 1531 BC).[30] The name Igigi seems to have originally been applied to the "great gods",[30] but it later came to refer to all the gods of Heaven collectively.[30] In some instances, the terms Anunnaki and Igigi are used synonymously.[23][24]

Major deities

Samuel Noah Kramer, writing in 1963, stated that the three most important deities in the Mesopotamian pantheon during all periods were the deities An, Enlil, and Enki.[31] However, newer research shows that the arrangement of the top of the pantheon could vary depending on time period and location. The Fara god list indicates that sometimes Enlil, Inanna and Enki were regarded as the three most significant deities.[32] Inanna was also the most important deity in Uruk and a number of other political centers in the Uruk period.[33] Gudea regarded Ninhursag, rather than Enki, as the third most prominent deity.[34] An Old Babylonian source preserves a tradition in which Nanna was the king of the gods, and Anu, Enlil and Enki merely his advisers,[35] likely a view espoused by Nanna's priests in Ur, and later on in Harran.[36] An Old Babylonian personal name refers to Shamash as "Enlil of the gods," possibly reflecting the existence of a similar belief connected to him among his clergy too, though unlike the doctrine of supremacy of the moon god, accepted by Nabonidus, it found no royal support at any point in time.[37] In Zabban, a city in the northeast of Babylonia, Hadad was the head of the pantheon.[38] In the first millennium BCE Marduk became the supreme god in Babylonia, and some late sources omit Anu and Enlil altogether and state that Ea received his position from Marduk.[39] In some neo-Babylonian inscriptions Nabu's status was equal to that of Marduk.[39] In Assyria, Assur was regarded as the supreme god.[40]

The number seven was extremely important in ancient Mesopotamian cosmology.[41][42] In Sumerian religion, the most powerful and important deities in the pantheon were sometimes called the "seven gods who decree":[43] An, Enlil, Enki, Ninhursag, Nanna, Utu, and Inanna.[44] Many major deities in Sumerian mythology were associated with specific celestial bodies:[45] Inanna was believed to be the planet Venus,[46][47] Utu was believed to be the Sun,[48][47] and Nanna was the Moon.[49][47] However, minor deities could be associated with planets too, for example Mars was sometimes called Simut,[50] and Ninsianna was a Venus deity distinct from Inanna in at least some contexts.[51]

| Name | Image | Major cult centers | Celestial body | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| An Anu[52] |

|

Eanna temple in Uruk[53] | Equatorial sky[54][47] | An (in Sumerian), later known as Anu (in Akkadian),[55] was the supreme God and "prime mover in creation", embodied by the sky.[52] He is the first and most distant ancestor,[52] theologically conceived as the God of Heaven in its "transcendental obscurity".[56] In some theological systems all of the deities were believed to be the offspring of An and his consort Ki.[52][57][24] However Anu was himself described as the descendant of various primordial beings in various texts (god lists, incantations, etc.), and Enlil was often equipped with his own elaborate family tree separate from Anu's.[58] While An was described as the utmost god,[59][52] at least by the time of the earliest written records the main god in terms of actual cult was Enlil.[60][61] Anu's supremacy was therefore "always somewhat nominal" according to Wilfred G. Lambert.[62] Luludanitu, a multicolored stone (red, white and black) was associated with him.[63] |

| Enlil Nunamnir, Ellil[64][65] |

|

Ekur temple in Nippur[66][67] | Northern sky[54][47] | Enlil, later known as Ellil, is the god of wind, air, earth, and storms[64] and the chief of all the gods.[68] The Sumerians envisioned Enlil as a benevolent, fatherly deity, who watches over humanity and cares for their well-being.[69] One Sumerian hymn describes Enlil as so glorious that even the other gods could not look upon him.[65][70] His cult was closely tied to the holy city of Nippur[67] and, after Nippur was sacked by the Elamites in 1230 BC, his cult fell into decline.[71] He was eventually paralleled in his role as chief deity by Marduk, the national god of the Babylonians,[71] and Assur, who fulfilled an analogous role for the Assyrians.[72] He was associated with lapis lazuli.[63][73] |

| Enki Nudimmud, Ninshiku, Ea[74] |

.jpg.webp) |

E-Abzu temple in Eridu[74] | Southern sky[54][47] | Enki, later known as Ea, and also occasionally referred to as Nudimmud or Ninšiku, was the god of the subterranean freshwater ocean,[74] who was also closely associated with wisdom, magic, incantations, arts, and crafts.[74] He was either the son of An, or the goddess Nammu,[74] and is the former case the twin brother of Ishkur.[74] His wife was the goddess Damgalnuna (Ninhursag)[74] and his children include the gods Marduk, Asarluhi, Enbilulu, the sage Adapa, and the goddess Nanshe.[74] His sukkal, or minister, was the two-faced messenger god Isimud.[74] Enki was the divine benefactor of humanity,[74] who helped humans survive the Great Flood.[74] In Enki and the World Order, he organizes "in detail every feature of the civilised world."[74] In Inanna and Enki, he is described as the holder of the sacred mes, the tablets concerning all aspects of human life.[74] He was associated with jasper.[63][73] |

| Marduk |  |

Babylon[75][71] | Jupiter[76] | Marduk is the national god of the Babylonians.[75] The expansion of his cult closely paralleled the historical rise of Babylon[75][71] and, after assimilating various local deities, including a god named Asarluhi, he eventually came to parallel Enlil as the chief of the gods.[75][71] Some late sources go as far as omitting Enlil and Anu altogether, and state that Ea received his position from Marduk.[39] His wife was the goddess Sarpānītu.[75] |

| Ashur |  |

Assur[77] | Ashur was the national god of the Assyrians.[77] It has been proposed that originally he was the deification of the city of Assur,[78] or perhaps the hill atop which it was built.[79] He initially lacked any connections to other deities, having no parents, spouse or children.[80] The only goddess related to him, though in an unclear way, was Šerua.[80] Later he was syncretized with Enlil,[81][72] and as a result Ninlil was sometimes regarded as his wife, and Ninurta and Zababa as his sons.[80] Sargon II initiated the trend of writing his name with the same signs as that of Anshar, a primordial being regarded as Anu's father in the theology of Enuma Elish.[72] He may have originally been a local deity associated with the city of Assur,[77] but, with the growth of the Assyrian Empire,[77] his cult was introduced to southern Mesopotamia.[82] In Assyrian texts Bel was a title of Ashur, rather than Marduk.[83] | |

| Nabu |  |

Borsippa,[84] Kalhu[85] | Mercury[84] | Nabu was the Mesopotamian god of scribes and writing.[84] His wife was the goddess Tashmetu[84] and he may have been associated with the planet Mercury,[84] though the evidence has been described as “circumstantial” by Francesco Pomponio.[86] He later became associated with wisdom and agriculture.[84] In the Old Babylonian and early Kassite periods his cult was only popular in central Mesopotamia (Babylon, Sippar, Kish, Dilbat, Lagaba), had a limited extent in peripheral areas (Susa in Elam, Mari in Syria) and there is little to no evidence of it from cities such as Ur and Nippur, in sharp contrast with later evidence.[87] In the first millennium BCE he became one of the most prominent gods of Babylonia.[87] In Assyria his prominence grew in the eighth and seventh centuries BCE.[85] In Kalhu and Nineveh he eventually became more common in personal names than the Assyrian head god Ashur.[85] He also replaced Ninurta as the main god of Kalhu.[85] In the Neo-Babylonian periods some inscriptions of kings such as Nebuchadnezzar II indicate that Nabu could take precedence even over the supreme Babylonian god Marduk.[85] His cult also spread beyond Mesopotamia, to cities such as Palmyra, Hierapolis, Edessa or Dura Europos,[88] and to Egypt, as far as Elephantine, where in sources from the late first millennium BCE he is the most frequently attested foreign god next to Yahweh.[88] |

| Nanna Enzu, Zuen, Suen, Sin[89] |

|

E-kiš-nu-ğal temple in Ur and another temple in Harran[49] | Moon[49] | Nanna, Enzu or Zuen ("Lord of Wisdom") in Sumerian, later altered as Suen and Sin in Akkadian,[89] is the ancient Mesopotamian god of the Moon.[49] He was the son of Enlil and Ninlil and one of his most prominent myths was an account of how he was conceived and how he made his way from the Underworld to Nippur.[49] A theological system where Nanna, rather than Enlil, was the king of gods, is known from a text from the Old Babylonian period;[90] in the preserved fragment Enlil, Anu, Enki and Ninhursag served as his advisers, alongside his children Utu and Inanna.[35] Other references to Nanna holding such a position are known from personal names and various texts, with some going as far as stating he holds "Anuship and Enlilship," and Wilfred G. Lambert assumes that he was regarded as the supreme god by his clergy in Ur and Harran.[36] |

| Utu Shamash[91] |

.jpg.webp) |

E-Babbar temples at Sippar and Larsa[92] | Sun[91] | Utu, later known as Shamash, is the ancient Mesopotamian god of the Sun,[91] who was also revered as the god of truth, justice, and morality.[92] He was the son of Nanna and the twin brother of Inanna. Utu was believed to see all things that happen during the day[92] and to aid mortals in distress.[92] Alongside Inanna, Utu was the enforcer of divine justice.[93] |

| Inanna Ishtar[94] |

|

Eanna temple in Uruk,[95][46][53] though she also had temples in Nippur, Lagash, Shuruppak, Zabalam, and Ur[95] | Venus[46] | Inanna, later known as Ishtar, is "the most important female deity of ancient Mesopotamia at all periods."[94] She was the Sumerian goddess of love, sexuality, prostitution, and war.[96] She was the divine personification of the planet Venus, the morning and evening star.[46] Accounts of her parentage vary;[94] in most myths, she is usually presented as the daughter of Nanna and Ningal,[97] but, in other stories, she is the daughter of Enki or An along with an unknown mother.[94] The Sumerians had more myths about her than any other deity.[98][99] Many of the myths involving her revolve around her attempts to usurp control of the other deities' domains.[100] Her most famous myth is the story of her descent into the Underworld,[101] in which she attempts to conquer the Underworld, the domain of her older sister Ereshkigal,[101] but is instead struck dead by the seven judges of the Underworld.[102][103][104] She is only revived due to Enki's intervention[102][103][104] and her husband Dumuzid is forced to take her place in the Underworld.[105][106] Alongside her twin brother Utu, Inanna was the enforcer of divine justice.[93] |

| Ninhursag Damgalnuna, Ninmah[107] |

E-Mah temple in Adab, Kesh[107] | Ninhursag ("Mistress of the mountain ranges"[108]), also known as Damgalnuna, Ninmah, Nintur[109] and Aruru,[110] was the Mesopotamian mother goddess. Her primary functions were related to birth (but generally not to nursing and raising children, with the exception of sources from early Lagash) and creation.[111] Descriptions of her as "mother" weren't always referring to motherhood in the literal sense or to parentage of other deities, but sometimes instead represented her esteem and authority as a senior deity, similar to references to major male deities such as Enlil or Anu as "fathers."[112] Certain mortal rulers claimed her as their mother,[107] a phenomenon recorded as early as during the reign of Mesilim of Kish (c. 2700 BCE).[113] She was the wife of Enki,[107] though in some locations (including Nippur) her husband was Šulpae instead.[114] Initially no city had Ninhursag as its tutelary goddess.[115] Later her main temple was the E-Mah in Adab,[107] originally dedicated to a minor male deity, Ašgi.[116] She was also associated with the city of Kesh,[107] where she replaced the local goddess Nintur,[110] and she was sometimes referred to as the "Bēlet-ilī of Kesh" or "she of Kesh".[107] It is possible her emblem was a symbol similar to later Greek letter omega.[117] | ||

| Ninurta Ninĝírsu[118] |

|

E-šu-me-ša temple in Nippur,[118] Girsu,[119] Lagash,[120][121] and later Kalhu in Assyria[122][123][124] | Saturn[125] | Ninurta, also known as Ningirsu, was a Mesopotamian warrior deity who was worshipped in Sumer from the very earliest times.[118] He was the champion of the gods against the Anzû bird after it stole the Tablet of Destinies from his father Enlil[118] and, in a myth that is alluded to in many works but never fully preserved, he killed a group of warriors known as the "Slain Heroes".[118] Ninurta was also an agricultural deity and the patron god of farmers.[118] In the epic poem Lugal-e, he slays the demon Asag and uses stones to build the Tigris and Euphrates rivers to make them useful for irrigation.[123] His major symbols were a perched bird and a plow.[126] |

| Nergal |  |

E-Meslam temple in Kutha and Mashkan-shapir[49] | Mars[127] | Nergal was associated with the Underworld[128] and is usually the husband of Ereshkigal.[128] He was also associated with forest fires (and identified with the fire-god, Gibil[129]), fevers, plagues, and war.[128] In myths, he causes destruction and devastation.[128] In the neo-Babylonian period in many official documents Nergal is listed immediately after the supreme gods Marduk and Nabu, and before such prominent deities as Shamash and Sin.[85] |

| Dumuzid Tammuz[130] |

|

Bad-tibira and Kuara[130] | Dumuzid, later known by the corrupted form Tammuz, is the ancient Mesopotamian god of shepherds[130] and the primary consort of the goddess Inanna.[130] His sister is the goddess Geshtinanna.[130][131] In addition to being the god of shepherds, Dumuzid was also an agricultural deity associated with the growth of plants.[132][133] Ancient Near Eastern peoples associated Dumuzid with the springtime, when the land was fertile and abundant,[132][134] but, during the summer months, when the land was dry and barren, it was thought that Dumuzid had "died".[132][135] During the month of Dumuzid, which fell in the middle of summer, people all across Sumer would mourn over his death.[136][137] An enormous number of popular stories circulated throughout the Near East surrounding his death.[136][137] | |

| Ereshkigal |  |

Kutha | Hydra[138] | Ereshkigal was the queen of the Mesopotamian Underworld.[139][140] She lived in a palace known as Ganzir.[139] In early accounts, her husband is Gugalanna,[139] whose character is undefined, but later the northern god Nergal was placed in this role.[139][140] Her gatekeeper was the god Neti[140] and her sukkal was Namtar.[139] In the poem Inanna's Descent into the Underworld, Ereshkigal is described as Inanna's "older sister".[141] In the god list An = Anum she opens the section dedicated to underworld deities.[142] |

| Gula and Ninisina, Nintinugga, Ninkarrak[143] |

|

E-gal-mah temple in Isin and other temples in Nippur, Borsippa, Assur,[143] Sippar,[144] Umma[145] | A prominent place in the Mesopotamian pantheon was occupied by healing goddesses,[146] regarded as divine patronesses of doctors and medicine-workers.[143] Multiple such deities existed:

Eventually Gula became the preeminent healing goddess,[145] and other healing goddesses were sometimes syncretised with her,[149] though in the god list An = Anum Gula, Ninkarrak and Nintinugga all figure as separate deities with own courts.[149] Dogs were associated with many healing goddesses[144] and Gula in particular is often shown in art with a dog sitting beside her.[143] | |

| Bau |  |

Lagash, Kish | Bau was a prominent goddess of Lagash, and some of its kings regarded her as their divine mother.[114] She was also a healing goddess, though unlike other healing goddesses she only developed such a function at some point in her history.[150] She was the wife of Ningirsu, and rose to prominence in third millennium BCE in the state of Lagash.[151] Gudea elevated Bau's rank to equal of that of Ningirsu, and called her "Queen who decides the destiny in Girsu."[152] This made her the highest ranking goddess of the local pantheon of Lagash,[153] putting her above Nanshe.[154] During the reign of the Third Dynasty of Ur, she was the second most notable "divine wife" after Ninlil,[155] with some sources (ex. from Nippur) indicating she was exalted above Ningirsu.[147] While the original Lagashite cult of Bau declined alongside the city,[156] she continued to be prominent in Kish in northern Babylonia, where she arrived in the Old Babylonian period.[157] The city god of Kish, Zababa, became her husband.[158] She remained a major goddess of that city as late as the neo-Babylonian period.[159] | |

| Ishkur Adad, Hadad[160] |

|

Karkar,[161] Assur,[162][163] Kurba'il[164] | Ishkur, later known as Adad or Hadad (from the root *hdd, "to thunder"[165]), was the Mesopotamian god of storms and rain.[160] In northern Mesopotamia, where agriculture relied heavily on rainfall, he was among the most prominent deities, and even in the south he ranked among the "great gods."[166] In god lists his position is similar to that of Sin, Shamash and Ishtar.[167] Ishkur is already attested as the god of Karkar in the Uruk period,[161] however evidence such as theophoric names indicates that the weather god's popularity only grew in later periods under the Akkadian name.[168] Hadad is already attested as the name of the weather god in early sources from Ebla.[165] In Mesopotamia these two gods started to merge in the Sargonic period,[169] and it seems it was already impossible to find a clear distinction between them in the Ur III period.[170] While northern texts put an emphasis on the benevolent character of the weather god as a bringer of rain, in the south he was often associated with destructive weather phenomena, including dust storms,[171] though even there he was credited with making plant growth possible in areas which weren't irrigated.[172] He was regarded as the son of An,[168] though less commonly he was also referred to as a son of Enlil.[173] His wife was Shala,[160] while his sukkal was Nimgir, the deified lightning.[174] In addition to being a weather god, Hadad was also a god of law and guardian of oaths,[175] as well as a god of divination (extispicy).[163] In these roles he was associated with Shamash.[163] In Zabban, a city in the northeast of Babylonia, he was regarded as the head of the local pantheon.[38] In Assyrian sources he was closely connected to military campaigns of the kings.[164] Kurba'il on the northern frontier of the empire was regarded as his most notable cult center in neo-Assyrian times.[164] In god lists foreign weather gods such as Hurrian Teshub ("Adad of Subartu"), Kassite Buriyaš or Ugaritic Baal were regarded as his equivalents.[176] | |

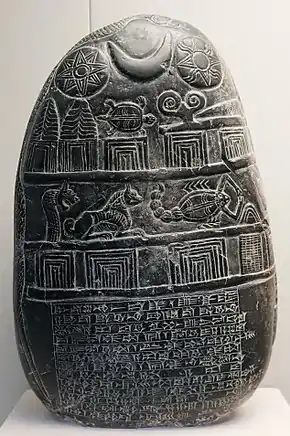

| Ištaran | Der[162] | Ištaran was a prominent[177] god, who served as the tutelary deity of the Sumerian city-state of Der, which was located east of the Tigris river on the border between Mesopotamia and Elam.[162] His wife was the goddess Šarrat-Dēri, whose name means "Queen of Der",[162] or alternatively Manzat (goddess of the rainbow),[177] and his sukkal was the snake-god Nirah.[162] He was regarded as a divine judge, and kings were said to "render justice like Ištaran."[178] A text from the late Early Dynastic Period invokes Ištaran to resolve a boundary dispute between the cities of Lagash and Umma.[162] In one of his inscriptions, King Gudea of Lagash mentions himself having installed a shrine for Ištaran in the temple of Ningirsu at Girsu[162] and describes Ištaran as a god of justice.[162] On kudurrus (boundary stones), Ištaran is often represented by a serpent, which may be Nirah[162] or Ištaran himself.[179] It is also possible that he's the god with an ophidian lower body known from cylinder seals.[177] In a ritual associated with the Ekur temple in Nippur, Ištaran is a "dying god" and is equated with Dumuzid.[179] A reference to Ištaran as a dying god appears also in a late text from Assur.[178] His national cult fell into decline during the Middle Babylonian Period,[162] though he still appeared in documents such as neo-Assyrian land grants.[180] However, in Der he continued to be venerated in later periods as well.[181] | ||

| Nanaya |  |

Uruk and Kish[182] | Corona Borealis[183] | Nanaya was a goddess of love[184] (including erotic love and lust).[185] She was commonly invoked in spells connected to this sphere.[186] Her worship was widespread, and she appears frequently in the textual record.[187] She was also involved in intercession and was regarded as "lady of lamma," a class of minor protective goddesses capable of interceding on behalf of humans.[188] She shared these roles with Ninshubur.[188] She was closely associated with Inanna/Ishtar,[189] though not identical to her as the two often appear side by side in the same texts: for example in Larsa Inanna, Nanaya and Ninsianna all functioned as distinct deities,[51] while in god lists Nanaya appears among Inanna's courtiers, usually following Dumuzi and Ninshubur.[190] In late sources Nanaya and Ishtar sometimes appear as goddesses of equal status.[191] In neo-Babylonian Uruk she was one of the most important deities, and retained this status under Persian rule as well.[192] There is also evidence for her worship continuing in Seleucid and Parthian times, as late as 45 CE.[193] |

| Nanshe |  |

Lagash[84] | Nanshe was a goddess associated with the state of Lagash,[194][49] whose cult declined with the loss of political relevance of that city.[159] She was a daughter of Enki and sister of Ningirsu.[49] She was associated with divination and the interpretation of dreams, but was also believed to assist the poor and the impoverished and ensure the accuracy of weights and measurements.[49] She was also associated with fish and waterfowl.[195] The First Sealand dynasty revived (or continued) her cult, making her the royal tutelary goddess.[159] | |

| Ninazu | Eshnunna and Enegi[196] | Ninazu was a god regarded as either the son of Ereshkigal or of Enlil and Ninil.[196] He was also the father of Ningishzida.[197] He was closely associated with the Underworld,[197] and some researchers go as far as proposing he was the oldest Mesopotamian god associated with it,[151] though it is most likely more accurate to say that there was initially no single universally agreed upon version of relevant mythical and cultic concepts, with various deities, both male and female, ruling over the Underworld in the belief systems of various areas and time periods.[198] Ninazu was also a Ninurta-like warrior god,[196] as well as the "king of snakes."[199] He was worshipped in Eshnunna during the third millennium BCE, but he was later supplanted there by Tishpak, who despite foreign origin had a similar character and attributes.[200] Ninazu was also worshipped at Enegi in southern Sumer.[196] His divine beast was the mušḫuššu, a serpentine dragon-like mythical creature, which was later also associated with Tishpak, Marduk (and by extension Nabu) and after Sennacherib's destruction of Babylon also with Ashur.[201] | ||

| Ninlil | Nippur, Assur,[202] Kish, Ḫursaĝkalama[203] | Ninlil was the wife of Enlil, the ruler of the gods.[107] She was not associated with any city of her own, serving primarily as Enlil's spouse,[204] and as such was probably an artificially created deity, invented as a female equivalent to Enlil.[107] She was nonetheless regarded as having power on par with Enlil;[205] in one poem, Ninlil declares, "As Enlil is your master, so am I also your mistress!"[205] In documents from the Ur III period, Ninlil was believed to be able to determine fates much like husband, and the pair was jointly regarded as the source of royal power by kings.[155] Sud, the tutelary goddess of Šuruppak, came to be regarded as one and the same as Ninlil, and the myth Enlil and Sud explain that Sud was the goddess' name before she married Enlil, receiving the name Ninlil.[159] However, Sud was originally an independent deity who was close in character to Sudag, an alternate name of the wife of Shamash; the confusion between Sudag and Sud(/Ninlil) is reflected in a myth where Ishum, normally regarded as the son of Shamash and his wife, is instead the son of Ninlil.[159] | ||

| Ninshubur |  |

Akkil;[206] worshipped with Inanna as her sukkal | Orion[207] | Assyriologists regard Ninshubur as the most commonly worshiped sukkal ("vizier"),[208] a type of deity serving as another's personal attendant. Her mistress was Inanna.[118][209] Many texts indicate they were regarded very close to each other, with one going as far as listing Ninshubur with the title "beloved vizier," before Inanna's relatives other than her husband Dumuzi.[210] She consistently appears as the first among Inanna's courtiers in god lists, usually followed by another commonly worshiped deity, Nanaya.[211] She was portrayed as capable of "appeasing" Inanna,[212] and as "unshakably loyal" in her devotion to her.[209] In the Sumerian myth of Inanna and Enki, Ninshubur rescues Inanna from the monsters that Enki sends to capture her,[213][214][209] while in Inanna's Descent into the Underworld, she pleads with the gods Enlil, Nanna and finally Enki in effort to persuade them to rescue Inanna from the Underworld.[215][216] She was regarded as a wise adviser[209] of her divine masters and human rulers alike.[208] In addition to being the sukkal of Inanna, she also served An[209] and the divine assembly.[217] In later Akkadian mythology, Ninshubur was syncretized with the male messenger deities Ilabrat and Papsukkal,[207] though this process wasn't complete until Seleucid times.[218] Ninshubur was popular[208] in the sphere of personal religion, for example as tutelary deity of a specific family, due to the belief she could mediate between humans and higher ranking gods.[219] |

| Nisaba | _and_an_inscription_from_Entemena%252C_ruler_of_Lagash%252C_circa_2430_BC%252C_chlorite%252C_Pergamon_Museum%252C_Berlin.jpg.webp) |

Eresh, later Nippur[220] | Nisaba was originally a goddess of grain and agriculture,[123] but, starting in the Early Dynastic Period, she developed into a goddess of writing, accounting, and scribal knowledge.[123] Her main cult city, Eresh, was evidently prominent in early periods, but after the reign of Shulgi almost entirely disappeared from records.[220] Texts mentioning Nisaba are sporadically attested as far west as Ebla and Ugarit, though it is uncertain if she was actively venerated further west than Mari.[221] Nisaba was the mother of the goddess Sud, syncretised with Enlil's wife Ninlil, and as a result she was regarded as his mother in law.[222] While a less common tradition identified her as the daughter of Enlil,[220] she was usually regarded as the daughter of Uraš, and references to Anu or Ea as her father are known from first millennium BCE literature.[220] Her husband was the god Haya.[123] There is little direct evidence for temples (in Nippur she was worshiped in the temple of her daughter Ninlil[223]) and clergy of Nisaba, but literary texts were commonly ended with the doxology "praise to Nisaba!" or other invocations of her.[223] The term "house of wisdom of Nisaba" attested in many texts was likely a generic term for institutions connected to writing.[223] Her importance started to decline (especially outside the scribal circles) after the Old Babylonian period, though attestations as late as from the reign of Nabopolassar are known.[224] | |

| Zababa | Kish[225][158] | Zababa was a war god who served as the tutelary deity of Kish.[158] His main temple was E-mete-ursag.[225] The earliest attestation of him comes from the Early Dynastic Period.[225] During the reign of Old Babylonian kings such as Hammurabi it was Zababa, rather than Ninurta, who was regarded as the primary war god.[226] He was initially regarded as a son of Enlil,[158] but Sennacherib called him a son of Ashur instead.[227] Initially his wife was Ishtar of Kish (regarded as separate from Ishtar of Uruk), but after the Old Babylonian period she was replaced by Bau in this role, and continued to be worshiped independently from him.[157] In some texts Zababa uses weapons usually associated with Ninurta and fights his mythical enemies, and on occasion he was called the "Nergal of Kish," but all 3 of these gods were regarded as separate.[228] In one list of deities he is called "Marduk of battle."[225] His primary symbol was a staff with the head of an eagle.[225] His sukkal was Papsukkal.[229] |

Primordial beings

Various civilizations over the course of Mesopotamian history had many different creation stories.[230][231] The earliest accounts of creation are simple narratives written in Sumerian dating to the late third millennium BC.[232][233] These are mostly preserved as brief prologues to longer mythographic compositions dealing with other subjects, such as Inanna and the Huluppu Tree, The Creation of the Pickax, and Enki and Ninmah.[234][232] Later accounts are far more elaborate, adding multiple generations of gods and primordial beings.[235] The longest and most famous of these accounts is the Babylonian Enûma Eliš, or Epic of Creation, which is divided into seven tablets.[233] The surviving version of the Enûma Eliš could not have been written any earlier than the late second millennium BC,[233] but it draws heavily on earlier materials,[236] including various works written during the Akkadian, Old Babylonian, and Kassite periods in the early second millennium BC.[236] A category of primordial beings common in incantations were pairs of divine ancestors of Enlil and less commonly of Anu.[58] In at least some cases these elaborate genealogies were assigned to major gods to avoid the implications of divine incest.[237]

Figures appearing in theogonies were generally regarded as ancient and no longer active (unlike the regular gods) by the Mesopotamians.[238]

| Name | Image | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Abzu | In the Babylonian creation epic, the Enûma Eliš, Abzu is primordial undeterminacy,[239] the consort of the goddess Tiamat who was killed by the god Ea (Enki).[239] Abzu was the personification of the subterranean primeval waters.[239] | |

| Alala and Belili | Alala and Belili were ancestors of Anu, usually appearing as the final pair in god lists accepting this tradition of his ancestry.[240] Alala was also adopted into Hurro-Hittite mythology[241] under the name Alalu.[242] It is possible Alala and Belili were paired together only because both names are iterative.[243] The name Belili could also refer to a goddess regarded as a sister of Dumuzi.[244] It has been argued that she was one and the same as the primordial deity,[245] but this view is not universally accepted and Manfred Krebernik argues it cannot be presently established if they were one and the same.[246] | |

| Anshar and Kishar | In some myths and god lists, Anshar and Kishar are a primordial couple, who are male and female respectively.[26] In the Babylonian Enûma Eliš, they are the second pair of offspring born from Abzu and Tiamat[26] and the parents of the supreme An.[26] A partial rewrite of Enûma Eliš from the neo-Assyrian period attempted to merge the roles of Marduk and Anshar, which Wilfred G. Lambert described as "completely superficial in that it leaves the plot in chaos by attributing Marduk's part to his great-grandfather, without making any attempt to iron out the resulting confusion."[247] In other late sources Anshar was sometimes listed among "conquered" mythical antagonists.[248] In a fragmentary text from Seleucid or Parthian times he is seemingly vanquished by Enki and an otherwise little known goddess Ninamakalla.[249] | |

| Dūri and Dāri | Dūri and Dāri (derived from an Akkadian phrase meaning "forever and ever"[241]) were ancestors of Anu according to the so-called "Anu theogony."[250] They represented "eternal time as a prime force in creation,"[240] and it is likely they developed as a personified form of a preexisting cosmological belief.[241] A single text identifies them as ancestors of Enlil instead.[250] They appear for the first time in an incantation from the reign of Samsu-iluna (Old Babylonian period).[241] | |

| Enki and Ninki | Enki and Ninki were two primordial beings who were regarded as the first generation among the ancestors of Enlil.[251] Enki and Ninki followed by a varying number of pairs of deities whose names start with "En" and "Nin" appear as Enlil's ancestors in various sources: god lists, incantations, liturgical texts,[252] and the Sumerian composition "Death of Gilgamesh," where the eponymous hero encounters these divine ancestors in the underworld.[253] The oldest document preserving this tradition is the Fara god list (Early Dynastic period).[254] Sometimes all the ancestors were collectively called "the Enkis and the Ninkis."[255] Enki, the ancestor of Enlil, is not to be confused with the god Enki/Ea, who is a distinct and unrelated figure.[256] The ancestral Enki's name means "lord earth," while the meaning of the name of the god of Eridu is uncertain but not the same, as indicated by some writings including an amissable g.[256] | |

| Enmesharra | Enmesharra was a minor deity of the underworld.[65] Seven, eight or fifteen other minor deities were said to be his offspring.[257] His symbol was the suššuru (a kind of pigeon).[65] He was sometimes regarded as the father of Enlil,[258] or as his uncle.[259] Texts allude to combat between Enmesharra and Enlil (or perhaps Ninurta), and his subsequent imprisonment.[260] In some traditions it was believed that this is how Enlil gained control over destinies.[261] In a late myth he was described as an enemy of Marduk.[262] | |

| Lugaldukuga | Lugaldukuga was the father of Enlil in some traditions,[259] though sometimes he was instead referred to as his grandfather.[263] Like Enmesharra he was regarded as a vanquished theogonic figure, and sometimes the two were equated.[264] He might be analogous to Endukuga, another ancestor of Enlil from god lists.[263] | |

| Nammu | Nammu is the primordial goddess who, in some Sumerian traditions, was said to have given birth to both An and Ki.[182] She eventually came to be regarded as the mother of Enki[182] and was revered as an important mother goddess.[182] Because the cuneiform sign used to write her name is the same as the sign for engur, a synonym for abzu, it is highly probable that she was originally conceived as the personification of the subterranean primeval waters.[182] | |

| Tiamat |  |

In the Babylonian creation epic, the Enûma Eliš, after the separation of heaven and earth, the goddess Tiamat and her consort Abzu are the only deities in existence.[265] A male-female pair, they mate and Tiamat gives birth to the first generation of gods.[265] Ea (Enki) slays Abzu[265] and Tiamat gives birth to eleven monsters to seek vengeance for her lover's death.[265] Eventually, Marduk, the son of Enki and the national god of the Babylonians, slays Tiamat and uses her body to create the earth.[265] In the Assyrian version of the story, it is Ashur who slays Tiamat instead.[265] Tiamat was the personification of the primeval waters and it is hard to tell how the author of the Enûma Eliš imagined her appearance.[265] |

Minor deities

| Name | Image | Major cult centers | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alammuš | worshiped with Nanna in Ur as his sukkal | Alammush was the sukkal of Nanna.[266] He appears very rarely in known literary texts, though in one case, possibly a fragment of a myth about Nanna going on a journey, he is described as "suitable for justice like Utu."[266] | |

| Ama-arhus | Uruk[267] | Ama-arhus (Nin-amaʾarḫuššu; "(lady) compassionate mother") was a sparsely attested Mesopotamian divinity, explained as a title of the medicine goddess Gula in one text.[268] It has been proposed that the presence of Ama-Arhus in late theophoric names from Uruk explains why Gula appears to not be attested in them, despite being worshiped in the city.[269] It is possible that she was merely viewed as her manifestation or synonym, as she is not otherwise attested in Uruk.[270] | |

| Amasagnudi | Uruk[267] | Amasagnudi was the wife of Papsukkal in the god list An = Anum[271] and in Seleucid Uruk.[272] According to one Old Babylonian text she was the sukkal of Anu,[272] and it has been proposed that she was originally an epithet of Ninshubur.[272] Assyriologist Frans Wiggermann translates her name as "mother who cannot be pushed aside."[273] | |

| Amashilama | Amashilama was the daughter of Ninazu and his wife Ningirida, and one of the two sisters of Ningishzida.[274] She is known from the god list An = Anum and a single mythical composition.[274] Thorkild Jacobsen identifies her as a leech goddess.[275] As noted by assyriologist Nathan Wasserman, however, leeches are only attested with certainty in late medical texts,[276] and the image of a leech in Mesopotamian literature is that of "a non-divine, harmful creature."[277] | ||

| Antu | Reš temple complex in Uruk[278] | Antu is a goddess who was invented during the Akkadian Period (c. 2334 BC – 2154 BC) as a consort for Anu,[52][59] and appears in such a role in the god list An = Anum.[279] Her name is a female version of Anu's own.[52][59] She was worshiped in the late first miilennium BCE in Uruk in the newly built temple complex dedicated to Anu.[280] Her elevation alongside her husband was connected to a theological trend under Achaemenid and Seleucid rule which extended their roles at the expense of Ishtar.[281] German classical scholar Walter Burkert proposed that the Greek goddess Dione, mentioned in Book V of the Iliad as the mother of Aphrodite, was a calque for Antu.[282] | |

| Anunītu | Agade[283] and Sippar-Amnanum[284] | Annunitum ("the martial one") was initially an epithet of Ishtar,[285] but later a separate goddess.[286] She is first attested in documents from the Ur III period.[287] She was a warrior goddess who shared a number of epithets with Ishtar.[288] It is possible she was depicted with a trident-like weapon on seals.[289] In documents from Sippar she sometimes appeared as a divine witness.[290] A similarly named and possibly related goddess, Annu, was popular in Mari.[291] | |

| Asarluhi | Kuara[292] | Asarluhi was originally a local god of the village of Kuara, which was located near the city of Eridu.[292] He eventually became regarded as a god of magical knowledge[292] and was thought to be the son of Enki and Ninhursag.[292] He was later absorbed as an aspect of Marduk.[292] In the standard Babylonian magical tradition, the name "Asarluhi" is used as merely an alternative name for Marduk.[292] | |

| Ashgi | Adab and Kesh[293] | Ashgi was one of the main gods of Adab in the Early Dynastic and Sargonic periods.[294] It is unclear if he was initially the spouse or the son of the goddess Nintu, analogous to Ninhursag.[151] In later periods he was viewed as her son, and her husband Shulpa'e is identified as his father in the god list An = Anum.[295] His mother replaced him as the tutelary deity of Adab in later periods.[151] | |

| Aruru | Kesh[296] | Aruru was initially a distinct minor goddess, regarded as violent and connected to vegetation;[110] however, despite lack of a connection to birth or creation she was later conflated with Ninhursag.[110] Sometimes she was syncretized with Nisaba instead, in which case the conflation was meant to highlight the latter's authority.[297] | |

| Aya Sherida, Nin-Aya |

Sippar and Larsa[298][299] | Sherida (Sumerian) or Aya (Akkadian) was the wife of the sun god Utu/Shamash and the goddess of dawn.[300] Her most common epithet was kallatum, which could be understood both as "bride" and "daughter in law".[301] She was especially popular during the Old Babylonian Period[302] and the Neo-Babylonian Period (626 BC – 539 BC).[298] | |

| Bēl-ṣarbi Lugal-asal[303] |

Šapazzu[304] | The name Bēl-ṣarbi means "lord of the poplar" (the tree meant is assumed to be Populus euphratica) in Akkadian.[303] He could also function as one of the gods connected with underworld.[303] | |

| Belet-Seri | Uruk[305] | Belet-Seri ("mistress of the steppe")[300] was a goddess who acted as the scribe of the underworld.[306] She could be identified with Geshtinanna or with Gubarra, the Sumerian name of the spouse of Amurru, Ashratum.[307] | |

| Bilgames Gilgamesh |

|

Uruk, a small village near Ur,[308] Lagash, Girsu, Der, Nippur[309] | Most historians generally agree that Gilgamesh was a historical king of the Sumerian city-state of Uruk,[308][310] who probably ruled sometime during the early part of the Early Dynastic Period (c. 2900–2350 BC).[308][310] It is certain that, during the later Early Dynastic Period, Gilgamesh was worshipped as a god at various locations across Sumer.[308] In the twenty-first century BC, Utu-hengal, the king of Uruk adopted Gilgamesh as his patron deity.[308] The kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur were especially fond of Gilgamesh, calling him their "divine brother" and "friend".[308] During this period, a large number of myths and legends developed surrounding him.[308] Probably during the Middle Babylonian Period (c. 1600 BC – c. 1155 BC), a scribe named Sîn-lēqi-unninni composed the Epic of Gilgamesh, an epic poem written in Akkadian narrating Gilgamesh's heroic exploits.[308] The opening of the poem describes Gilgamesh as "one-third human, two-thirds divine".[308] Very little evidence of worship of Gilgamesh comes from times later than the Old Babylonian period.[311] A late source states that he was worshiped during ceremonies connected to the dead, alongside Dumuzi and Ninishzida.[312] In incantations he commonly appeared alongside minor underworld deities such as Ningishzida, Geshtinanna, or Namtar and his family.[313] There are also attestations of Gilgamesh as a servant of Nergal and Ereshkigal, specifically a ferryman of the dead.[314] |

| Birtum | Birtum was the husband of the prison goddess Nungal.[315] The name, which means "fetter" or "shackle" in Akkadian, is grammatically feminine, but designates a male deity.[315] | ||

| Bitu | Bitu's primary function is that of a gatekeeper (ì-du8) of the underworld.[316] In older publications his name was read as Neti.[317] In Inanna's Descent into the Underworld, he leads Inanna through the seven gates of the underworld, removing one of her garments at each gate so that when she comes before Ereshkigal she is naked and symbolically powerless.[318] | ||

| Bizilla | Ḫursaĝkalama[319] | Bizilla was a goddess closely associated with Nanaya.[320] It is assumed that like her she was a love goddess.[321] She was also most likely regarded as the sukkal of Enlil's wife Ninlil in Ḫursaĝkalama, her cult center located near Kish.[319][203] | |

| Bunene | Sippar, Uruk, and Assur[92] | Bunene was the sukkal and charioteer of the sun-god Utu.[92] He was worshipped at Sippar and Uruk during the Old Babylonian Period[92] and later worshipped at Assur.[92] According to some accounts, he may have been Utu's son.[92] However, in Sippar he was regarded as the son in law of Utu's Akkadian counterpart Shamash instead, and the daughter of Shamash and Aya, Mamu (or Mamud) was his wife.[288] | |

| Damu | Isin, Larsa, Ur, and Girsu[322] | Damu was a god who presides over healing and medicine.[322] He was the son of Ninisina or of Gula.[150] In some texts, "Damu" is used as another name for Dumuzid,[323] but this may be a different word meaning "son".[323] Another god named "Damu" was also worshipped in Ebla and Emar,[322] but this may be a local hero, not the same as the god of healing.[322] According to Alfonso Archi, the Eblaite Damu should be understood as the deified concept of a kinship group rather than a personified deity.[324] The official cult of Damu became extinct sometime after the Old Babylonian Period.[322] | |

| Dingirma | Kesh[110] | Dingirma was a goddess from Kesh regarded as analogous to Ninhursag.[325] Her name means "exalted deity."[114] While in literary texts the names Dingirma and Ninhursag can alternate, administrative texts from Kesh exclusively use the former.[110] | |

| Dumuzi-abzu | The state of Lagash,[326] especially Kinunir[136] | Dumuzi-abzu is a local goddess who was the tutelary goddess of Kinunir, a settlement in the territory of the state of Lagash.[326] Her name, which probably means "good child of the Abzu",[136] was sometimes abbreviated to Dumuzi,[136] but she has no obvious connection to the god Dumuzi.[136] It is possible that in Early Dynastic and Sargonic sources the name Dumuzi often referred to Dumuzi-abzu and not to the husband of Inanna.[327] It is assumed that she belonged to the circle of deities connected to Nanshe.[328] It is possible Dumuzi-abzu was regarded as the wife of Hendursaga in the third millennium BCE.[110] | |

| Duttur | Duttur was the mother of Dumuzi.[329] Thorkild Jacobsen proposed that she should be understood as a deification of the ewe (adult female sheep).[330] However, her name shows no etymological affinity with any attested terms related to sheep, and it has been suggested that while she was definitely a goddess associated with livestock and pastoralism, she was not necessarily exclusively connected with sheep.[330] | ||

| Emesh | Emesh is a farmer deity in the Sumerian poem Enlil Chooses the Farmer-God (ETCSL 5.3.3), which describes how Enlil, hoping "to establish abundance and prosperity", creates two gods: Emesh and Enten, a farmer and a shepherd respectively.[331] The two gods argue and Emesh lays claim to Enten's position.[332] They take the dispute before Enlil, who rules in favor of Enten.[333] The two gods rejoice and reconcile.[333] | ||

| Enbilulu | Babylon[334] | Enbilulu was the god of irrigation.[335] In early dynastic sources the name Ninbilulu is also attested, though it's uncertain if it should be considered an alternate form, or a separate, possibly female, deity.[335] The relation between Enbilulu, Ninbilulu and Bilulu from the myth Inanna and Bilulu also remains uncertain.[335] | |

| Enkimdu | possibly Umma[336] | Enkimdu is described as the "lord of dike and canal".[65] His character has been compared to Enbilulu's.[337] It has been proposed that he was worshiped in Umma as the personification of the irrigation system, though the evidence is scarce.[336] ppears in the myth Enkimdu and Dumuzi.[338] The text has originally been published under the title Inanna prefers the farmer by Samuel Noah Kramer in 1944.[339] Initially it was assumed that it would end with Inanna choosing Enkimdu, but this interpretation was abandoned after more editions were compiled.[339] In laments, he could be associated with Amurru.[340] It has been pointed out that Dumuzi does not appear in any of the texts where Enkimdu occurs alongside Amurru, which might indicate that in this case the latter was meant to serve as a shepherd god contrasted with Enkimdu in a similar way.[341] | |

| Enlilazi | Nippur | Enlilazi was a minor god regarded as the "superintendent of Ekur."[342] | |

| Ennugi | Nippur[343] | Ennugi was a god regarded as "lord of ditch and canal"[344] and "chamberlain of Enlil."[345] Based on similar meaning of the name Gugalanna to the former title, it has been proposed that they might have been analogous.[139] | |

| Enten | Enten is a shepherd deity in the Sumerian poem Enlil Chooses the Farmer-God (ETCSL 5.3.3), which describes how Enlil, hoping "to establish abundance and prosperity", creates two gods: Emesh and Enten, a farmer and a shepherd respectively.[331] The two gods argue and Emesh lays claim to Enten's position.[332] They take the dispute before Enlil, who rules in favor of Enten.[333] The two gods rejoice and reconcile.[333] | ||

| Erra |  |

Kutha[346] | Erra is a warlike god who is associated with pestilence and violence.[347][348] He is the son of the sky-god An[347] and his wife is an obscure, minor goddess named Mami, who is different from the mother goddess with the same name.[347][349] As early as the Akkadian Period, Erra was already associated with Nergal[347][348] and he eventually came to be seen as merely an aspect of him.[347][348] The names came to be used interchangeably.[347] |

| Erragal Errakal |

Erragal, also known as Errakal, is a relatively rarely-attested deity who was usually regarded as a form of Erra,[348] but the two gods are probably of separate origin.[350] He is connected with storms and the destruction caused by them.[349] In An = Anum I 316, Erragal is listed as the husband of the goddess Ninisig and is equated with Nergal.[349] in the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Atra-Hasis Epic, Errakal is said to "tear up the mooring poles", causing the Great Flood.[349] | ||

| Ezina Ashnan |

Adab, Lagash, Umma, Ur,[351] Shuruppak[108] | Ezina, or Ashnan in Akkadian,[351] was a goddess of grain.[351] She was commonly associated with Kusu, a goddess of purification.[352] In the Sumerian poem The Dispute between Cattle and Grain, she and Lahar are created by the Anunnaki to provide them with food.[353] They produce large amounts of food,[354] but become drunk with wine and start to quarrel, so Enki and Enlil intervene, declaring Ashnan the victor.[355] | |

| Gareus | Uruk | Gareus was a god introduced to Uruk during late antiquity by the Parthians,[356] who built a small temple to him there in around 100 AD.[356] He was a syncretic deity, combining elements of Greco-Roman and Babylonian cults.[356] | |

| Gazbaba | Gazbaba was a goddess closely associated with Nanaya, like her connected with erotic love.[357] Šurpu describes her as ṣayyaḫatu, "the smiling one," which is likely a reference to the frequent mention of smiles in Akkadian erotic literature.[357] Her name is derived from the Akkadian word kazbu, which can be translated as "sexual attraction."[357] | ||

| Geshtinanna | Nippur, Isin, and Uruk[358] | Geshtinanna was a rural agricultural goddess sometimes associated with dream interpretation.[359] She was the sister of Dumuzid, the god of shepherds.[359] In one myth, she protects her brother when the galla demons come to drag him down to the Underworld by hiding him in successively in four different places.[359] In another myth about Dumuzid's death, she refuses to tell the galla where he is hiding, even after they torture her.[359] The galla eventually take Dumuzid away after he is betrayed by an unnamed "friend",[359] but Inanna decrees that he and Geshtinanna will alternate places every six months, each spending half the year in the Underworld while the other stays in Heaven.[359] While she is in the Underworld, Geshtinanna serves as Ereshkigal's scribe.[359] In Lagash she was regarded as the wife of Ningishzida, and was associated with his symbol, mushussu.[360] According to Julia M. Asher-Greve she was connected in myths to Geshtindudu, another minor goddess, by friendship alone, an uncommon connection between otherwise unrelated Mesopotamian goddesses.[361] | |

| Gibil |  |

Gibil is the deification of fire.[359] According to Jeremy Black and Anthony Green, he "represented fire in all its aspects: as a destructive force and as the burning heat of the Mesopotamian summer; and as a creative force, the fire in the blacksmith's furnace and the fire in the kiln where bricks are baked, and so as a 'founder of cities'."[359] He is traditionally said to be the son of An and Shala,[359] but is sometimes the son of Nusku.[362] | |

| Gugalanna | Gugalanna is the first husband of Ereshkigal, the queen of the Underworld.[139] His name probably originally meant "canal inspector of An"[139] and he may be merely an alternative name for Ennugi.[139] The son of Ereshkigal and Gugalanna is Ninazu.[139] In Inanna's Descent into the Underworld, Inanna tells the gatekeeper Neti that she is descending to the Underworld to attend the funeral of "Gugalanna, the husband of my elder sister Ereshkigal".[139][363][141] | ||

| Gunura | Gunura was the daughter of Ninisina and thus sister of Damu.[150] She was not associated with other healing goddesses, such as Ninkarrak.[150] | ||

| Ĝatumdug | Lagash[361] | Ĝatumdug was a goddess from the early pantheon of Lagash.[361] While the meaning of her name is unknown, she was described as the city's mother,[364] or its founder.[365] According to inscriptions of Gudea she assigned a lamma (tutelary deity) to him.[25] She was later equated with Bau.[366] | |

| Haya | Umma, Ur, and Kuara.[367] | Haya is the husband of the goddess Nisaba.[123][367] Haya was primarily a god of scribes,[367] but he may have also been associated with grain and agriculture.[367] He also served as a doorkeeper.[367] In some texts, he is identified as the father of the goddess Ninlil.[367] He was worshipped mostly during the Third Dynasty of Ur, when he had temples in the cities of Umma, Ur, and Kuara.[367] In later times, he had a temple in the city of Assur and may have had one in Nineveh.[367] A god named Haya was worshipped at Mari, but this may have been a different deity.[367] | |

| Ḫegir Ḫegirnunna |

Girsu[368] | Ḫegir, later known as Ḫegirnunna,[369] was one of the seven deities referred to as "septuplets of Bau" or "seven lukur priestesses of Ningirsu."[370] Her name can be translated as "the maid of the (lofty) way" and refers to a route of processions in Girsu in the state of Lagash.[369] | |

| Hendursaga | Girsu[371] | Hendursaga was a Sumerian god described as "protective god with a friendly face" in inscriptions.[219] He was believed to guard streets and gates at night.[219] King Gudea of Lagash refers to him as the "herald of the land of Sumer" in one inscription.[372] His wife might have originally been Dumuzi-abzu, though later he was regarded as the husband of Ninmug due to syncretism between him and Ishum.[110] | |

| Humhum | Dūr-Šarruku[373] | Humhum was a minor god worshiped in Dūr-Šarruku (also known as Sippar-Aruru) in northern Babylonia.[373] Esarhaddon returned his statue to a temple located there.[373] | |

| Idlurugu Id[374] |

Id (modern Hit)[375] | Idlurugu was a god who represent the concept of trial by ordeal, specifically river ordeal. The term i7-lú-ru-gú, "the river that receives man"[376] or "the river which confronts man," could refer both to him and to the procedure.[377] | |

| Igalima | Lagash[378] | Igalima was a son of Bau and Ninĝirsu.[378] In offering lists he appears next to Shulshaga.[379] | |

| Ilaba | Agade[46] | Ilaba was briefly a major deity during the Sargonic period,[46] but seems to have been completely obscure during all other periods of Mesopotamian history.[46] He was closely associated with the kings of the Akkadian Empire.[96] | |

| Ilabrat | Assur,[380] a town near Nuzi[381] | Ilabrat was the sukkal, or personal attendant, of Anu.[59][382] He appears in the myth of Adapa in which he tells Anu that the reason why the south wind does not blow is because Adapa, the priest of Ea in Eridu, has broken its wing.[382] | |

| Ishmekarab | Shamash's temple Ebabbar[383] in Larsa[384] | One of the 11[384] "standing gods of Ebabbar," divine judges assisting Shamash,[383] as well as a member of various Assyrian groups of judge deities.[385] While Akkadian in origin (the name means "he (or she) heard the payer),[383] Ishmekarab also appears in Elamite sources as an assistant of judge god Inshushinak, both in legal documents[383] and in texts about the underworld.[386][387] Ishmekarab's gender is unclear, but Wilfred G. Lambert considered it more likely that this deity was male.[388] | |

| Irnina | Irnina was the goddess of victory.[389] She could function as an independent deity from the court of Ningishzida, but also as a title of major goddesses.[178] | ||

| Isimud |  |

Worshipped with Enki as his sukkal | Isimud, later known as Usmû, was the sukkal, or personal attendant, of Enki.[160] His name is related to the word meaning "having two faces"[160] and he is shown in art with a face on either side of his head.[160] He acts as Enki's messenger in the myths of Enki and Ninhursag and Inanna and Enki.[160] |

| Ishum | Ishum was a popular, but not very prominent god,[390] who was worshipped from the Early Dynastic Period onwards.[390] In a fragmentary myth, he is described as the son of Shamash and Ninlil,[390] but he was usually the son of Shamash and his wife Aya.[159] The former genealogy was likely the result of confusion between Sud (Ninlil) and Sudag, a title of the sun god's wife.[159] He was a generally benevolent deity, who served as a night watchman and protector.[390] He may be the same god as the Sumerian Hendursaga, because the both of them are said to have been the husband of the goddess Ninmug.[390] He was sometimes associated with the Underworld[390] and was believed to exert a calming influence on Erra, the god of rage and violence.[390] | ||

| Kabta | Kabta was a deity commonly paired with Ninsianna.[391] | ||

| Kakka | Maškan-šarrum[392] | Kakka was the sukkal of both Anu (in Nergal and Ereshkigal)[393] and Anshar (in the god list An = Anum and in Enuma Elish).[394] Kakka is not to be confused with a different unrelated deity named Kakka, known from Mari, who was a healing goddess associated with Ninkarrak[394] and Ninshubur.[291] | |

| Kanisurra | Uruk,[395] Kish[396] | Kanisurra (also Gansurra, Ganisurra)[396] was a goddess from the entourage of Nanaya.[395][397] She was known as bēlet kaššāpāti, "lady of the sorceresses."[395] However, her character and functions remain unclear.[395][397] It has been proposed that her name was originally a term for a location in the netherworld due to its similarity to the Sumerian word ganzer, the entrance to the underworld.[398] In late theological sources she was regarded as Nanaya's hairdresser and one of the two "daughters of Ezida."[399] | |

| Ki | Umma, Lagash[352] | Ki was a Sumerian goddess who was the personification of the earth.[390] In some Sumerian accounts, she is a primordial being who copulates with An to produce a variety of plants.[400] An and Ki collectively were an object of worship in Umma and Lagash in the Ur III period,[352] but the evidence for worship of her is scarce and her name was sometimes written without the dingir sign denoting divinity.[401] A fragmentary late neo-Assyrian god list appears to consider her and another figure regarded as the wife of Anu, Urash, as one and the same, and refers to "Ki-Urash."[402] | |

| Kittum | Bad-Tibira, Rahabu[403] | Kittum was a daughter of Utu and Sherida.[404] Her name means "Truth".[404] | |

| Kus | Kus is a god of herdsmen referenced in the Theogony of Dunnu.[405] | ||

| Kusu | Lagash,[352] Nippur[406] | Kusu was a goddess of purification, commonly invoked in Akkadian šuillakku, a type of prayers asking for help with an individual's problems.[300] She was regarded as the personification of a type of ritual censer.[352] A late text states that "the duck is the bird of Kusu."[407] | |

| Lagamar | Dilbat[408][409] | Lagamar, whose name means "no mercy" in Akkadian[410] was a minor god worshiped in Dilbat[408] as the son of the city's tutelary god, Urash (not to be confused with the earth goddess).[411] He was associated with the underworld.[410] He was also worshiped in Elam, where he was associated with Ishmekarab[411] and the underworld judge Inshushinak.[386][387] | |

| Laguda | Nēmed-Laguda[412] | Laguda was a god associated with the Persian Gulf.[412] He appears in the text Marduk's Address to the Demons, according to which he exalted the eponymous god in the "lower sea."[413] He could be associated with other deities with marine associations, such as Sirsir and Lugal'abba.[413] | |

| Lahar | Lahar was a god associated with sheep.[414] Research shows that he was usually regarded as a male deity,[415] though he was initially interpreted as a goddess in Samuel Noah Kramer's translations.[415] In the poem The Dispute between Cattle and Grain, Lahar and Ashnan are created by the Anunnaki to provide them with food.[353] They produce large amounts of food,[354] but become drunk with wine and start to quarrel, so Enki and Enlil intervene, declaring Ashnan the victor.[355] | ||

| Laṣ | Kutha,[416] Lagaba[417] | Laṣ was one of the goddesses who could be regarded as the wife of Nergal.[416] In Babylonia, she became the goddess most commonly identified as such starting with the reign of Kurigalzu II.[418] In Assyria, an analogous phenomenon is attested from the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III onward.[418] In the Old Babylonian period, Nergal's wife was usually Mammitum.[419] Wilfred G. Lambert proposed that Laṣ was a goddess of healing, as an explanatory version of the Weidner god list equates her with Bau, while other similar documents place her in the proximity of Gula, who were both regarded as such.[419] | |

| Lisin | Adab and Kesh[293] | Lisin and her brother Ashgi were worshipped in Adab and Kesh.[293] Her husband was the god Ninsikila.[293] In Sumerian times, Lisin was viewed as a mother goddess.[293] She is identified with the star α Scorpionis.[293] Later, Ninsikila's and Lisin's genders were swapped.[420] | |

| Lugala'abba | Nippur[421] | Lugala'abba ("Lord of the Sea"[422]) was a god associated both with the sea and with the underworld.[423] | |

| Lugalbanda | Uruk, Nippur, and Kuara[424] | Lugalbanda was an early legendary king of the Sumerian city-state of Uruk, who was later declared to be a god.[424] He is the husband of the goddess Ninsun and the father of the mortal hero Gilgamesh.[424] He is mentioned as a god alongside Ninsun in a list of deities as early as the Early Dynastic Period.[424] A brief fragment of a myth about him from this same time period is also preserved.[424] During the Third Dynasty of Ur, all the kings would offer sacrifices to Lugalbanda as a god in the holy city of Nippur.[424] Two epic poems about Lugalbanda describe him successfully crossing dangerous mountains alone, though hindered by severe illness.[424] The Sumerian King List makes him a shepherd, who reigned for 1,200 years.[424] He has a close relationship with the goddess Inanna.[424] | |

| Lugal-irra and Meslamta-ea |  |

Kisiga[424] | Lugal-irra and Meslamta-ea are a set of twin gods who were worshipped in the village of Kisiga, located in northern Babylonia.[424] They were regarded as guardians of doorways[425] and they may have originally been envisioned as a set of twins guarding the gates of the Underworld, who chopped the dead into pieces as they passed through the gates.[426] During the Neo-Assyrian period, small depictions of them would be buried at entrances,[425] with Lugal-irra always on the left and Meslamta-ea always on the right.[425] They are identical and are shown wearing horned caps and each holding an axe and a mace.[425] They are identified with the constellation Gemini, which is named after them.[425] |

| Lulal Latarak |

Bad-tibira[427][428] | Lulal, also known as Latarak in Akkadian,[428] was a god closely associated with Inanna,[427] but their relationship is unclear and ambiguous.[427] He appears in Inanna's Descent into the Underworld.[427] He seems to have primarily been a warrior-god,[427] but he was also associated with domesticated animals.[427] One hymn calls him the "master of the open country."[428] | |

| Lumma | Nippur and Umma[429] | Reading of the theonym LUM-ma is unclear.[430] The god bearing it was regarded as a guardian (udug) of Ekur, Enlil's temple in Nippur,[431] or as an underworld demon (gallû).[431] Gianni Marchesi describes him as "gendarme demon par excellence."[431] He was regarded as a figure of low rank, serving under other deities,[431] but nonetheless capable of rewarding righteousness.[431] The goddess Ninmug was his mother according to the text of a Sumerian lamentation.[429] It has been proposed that he was originally a deified human ruler.[342] Similar origin has been proposed for a number of other gods of similar character, such as Ḫadaniš (who shares his name with a king of Hamazi)[342] | |

| Mami Mama |

Mami or Mama is a mother goddess whose name means "mother".[84] She may be the same goddess as Ninhursag.[84] | ||

| Mammitum | Kutha[416] | Mammitum was one of the goddesses who could be identified as the wife of Nergal.[416] In the Old Babylonian period, she is the best attested among them.[419] It is possible she was originally the wife of Erra rather than Nergal, and was only introduced to Kutha alongside him.[416] Her name might mean "oath" or "frost" (based on similarity to the Akkadian word mammû, "ice" or "frost").[432] As her name is homophonous with Mami, a goddess of birth or "divine midwife,"[433] some researchers assume they are one and the same.[416] However, it has been proven that they were separate deities,[433] | |

| Mamu | Sippar[434] | Mamu or Mamud was the daughter of Aya and Shamash,[435] worshiped in Sippar.[434] She was the goddess of dreams.[290] Her husband was Bunene.[288] | |

| Mandanu | Babylon, Kish[343] | Mandanu was a divine judge, attested after the Old Babylonian period, but absent from older god lists such as the so-called Weidner and Nippur lists.[436] According to assyriologist Manfred Krebernik he can be considered a personification of places of judgment.[436] He belonged to the circle of deities associated with Marduk.[437] | |

| Manzat | Der[438] | Manzat ("Rainbow") was the Akkadian goddess of the rainbow.[439] She was worshiped in Der,[438] and was sometimes viewed as the wife of the city's tutelary god, Ishtaran.[177] Her titles, such as "Lady of regulations of heaven" and "Companion of heaven" highlighted her astral character,[439] though she was also associated with prosperity of cities.[440] Outside Mesopotamia she was also worshiped in Elam, where she was possibly regarded as the wife of Simut.[440] | |

| Martu Amurru |

Babylon,[441] Assur[442] | Martu, in Akkadian known as Amurru, was the divine personification of the nomads who began to appear on the edges of the Mesopotamian world in the middle of the third millennium BC, initially from the west, but later from the east as well.[443] He was described as a deity who "rages over the land like a storm".[443] One myth describes how the daughter of the god Numušda insists on marrying Martu, despite his unattractive habits.[444] In Old Babylonian and Kassite art, Amurru is shown as a god dressed in long robes and carrying a scimitar or a shepherd's crook.[5] | |

| Misharu | Misharu ("justice") was a son of Adad and Shala.[445] His wife was Ishartu ("righteousness").[445] | ||

| Nanibgal | Eresh[446] | Nanibgal was initially a title or alternate name of Nisaba, but eventually developed into a distinct goddess attested in the god list An = Anum and in a number of rituals.[220] She had her own spouse, Ennugi, and own distinct role as a courtier of Ninlil.[220] | |

| Nimintabba | Ur[447] | Nimintabba was a minor goddess who belonged to the entourage of Nanna, the tutelary god of Ur.[447] She had a temple in Ur during the reign of king Shulgi.[447] It is possible she was initially a deity of greater theological importance, but declined with time.[448] | |

| Nindara | Girsu,[446] Ki'eša[449] | Nindara was the husband of Nanshe.[450] | |

| Ninegal Belet Ekallim[451] |

Nippur,[451] Umma,[452] Lagash,[452] Dilbat[300][453] | Ninegal or Ninegalla, known in Akkadian as Belet Ekallim[451] (both meaning "lady of the palace")[454] was a minor[455] goddess regarded as a tutelary deity of palaces of kings and other high-ranking officials.[455] She was the wife of Urash, the city god of Dilbat,[300] and was worshiped alongside him and their son Lagamar in some locations.[453] "Ninegal" could also function as an epithet of other deities, especially Inanna,[452] but also Nungal.[456] Outside Mesopotamia she was popular in Qatna, where she served as the tutelary goddess of the city.[453] | |

| Ningal Nikkal[457] |

Ekišnuĝal temple in Ur[458] and Harran[457] | Ningal ("great queen"[459]), later known by the corrupted form Nikkal, was the wife of Nanna-Suen, the god of the moon, and the mother of Utu, the god of the sun.[457] Though she was worshiped in all periods of ancient Mesopotamian history, her role is described as "passive and supportive" by researchers.[459] | |

| Ningikuga | Ur[460] | Ningikuga is a goddess of reeds and marshes.[461] Her name means "Lady of the Pure Reed".[461] She is the daughter of Anu and Nammu[461] and one of the many consorts of Enki.[461] | |

| Ningirida | Ningirida was the wife of Ninazu and mother of Ningishzida and his two sisters.[274] A passage describing Ningirida taking care of baby Ningishzida is regarded as one of the only references to deities in their infancy and to goddesses breastfeeding in Mesopotamian literature.[462] | ||

| Ninhegal | Sippar | Ninhegal was a goddess of abundance worshiped in Sippar.[434] It is possible she can be identified as the goddess depicted with streams of water on seals from that city.[434] | |

| Ninimma | Nippur[406] | Ninimma was a courtier of Enlil regarded as his scribe and sometimes as the nurse of his children.[463][462] Like other goddesses from Enlil's circle she had a temple in Nippur.[406] In the myth Enki and Ninmah she's one of the seven birth goddesses,[464] the other 6 being Shuzianna, Ninmada, Ninshar, Ninmug, Mumudu and Ninniginna.[465] Her husband was Guškinbanda,[466] called "Ea of the goldsmith" in an explanatory text.[463] Occasional references to Ninimma as a male deity are also known,[467] and in this context he was called "Ea of the scribe."[463] | |

| Ninkilim |  |

Ninkilim was a deity who was associated with mongooses, which are common throughout southern Mesopotamia.[468] According to a Babylonian popular saying, when a mouse fled from a mongoose into a serpent's hole, it announced, "I bring you greetings from the snake-charmer!"[468] A creature resembling a mongoose also appears in Old Babylonian glyptic art,[468] but its significance is not known.[468] | |

| Ningirima | Muru,[469] Girima near Uruk[470] | Ningirama was a goddess[470] associated with incantations, water, and fish,[470] and who was invoked for protection against snakes.[468] It has been argued that she was conflated with Ningilin, the deity of mongooses, at an early date,[468] but she is a distinct deity as late as during the reign of Esarhaddon.[471] | |

| Ningishzida |  |

Lagash[472] | Ningishzida is a god who normally lives in the Underworld.[457] He is the son of Ninazu and his name may be etymologically derived from a phrase meaning "Lord of the Good Tree".[457] In the Sumerian poem, The Death of Gilgamesh, the hero Gilgamesh dies and meets Ningishzida, along with Dumuzid, in the Underworld.[472] Gudea, the Sumerian king of the city-state of Lagash, revered Ningishzida as his personal protector.[472] In the myth of Adapa, Dumuzid and Ningishzida are described as guarding the gates of the highest Heaven.[473] Ningishzida was associated with the constellation Hydra.[107] |

| Ningublaga | Kiabrig,[474] Ur,[475] Larsa[476] | Ningublaga was associated with cattle.[477] He was believed to oversee the herds belonging to the moon god Nanna.[478] Consumption of beef was regarded as taboo to him.[477] He also had an apotropaic role, and appears in many incantations, for example against scorpion bite.[477] | |

| Ninigizibara | Umma,[479] Uruk[480] | Ninigizibara was a deified harp who could be regarded as an advisor of Inanna.[479] | |

| Ninkasi | Shuruppak,[108] Nippur[406] | Ninkasi was the goddess of beer.[420] She was associated with Širaš, the goddess of brewing.[481] In one hymn her parents are said to be Enki and Ninti,[481] though it also states she was raised by Ninhursag.[481] Sometimes Ninkasi was viewed as a male deity.[420] In the so-called Weidner god list, Ninkasi appears among chthonic deities alongside the prison goddess Nungal.[482] | |

| Ninkurra | Ninkurra is the daughter of Enki and Ninsar.[483] After having sex with her father Enki, Ninkurra gave birth to Uttu, the goddess of weaving and vegetation.[483] | ||

| Ninmada | Ninmada was a god regarded as a brother of Ninazu,[178] who was described as a snake charmer in the service of An or Enlil.[178] A goddess bearing the same name appears among the assistants of Ninmah in the myth Enki and Ninmah.[465] | ||

| Nin-MAR.KI Ninmar?[484] |

Ḫurim,[485] Guabba,[486] Lagash[361] | Nin-MAR.KI (reading uncertain) was the daughter of Nanshe.[360] | |

| Ninmena | Utab[487] | Ninmena was a Sumerian goddess of birth[488] whose name means "Lady of the Crown".[84][433] Although syncretised with more prominent similar goddesses (like Ninhursag) in literary texts, she never fully merged with them in Sumerian tradition.[489] | |

| Ninmug | Kisiga,[490] Shuruppak[108] | Ninmug was the tutelary goddess of metal workers.[491] She was the wife of the god Ishum, and by extension also of Hendursaga in later periods.[110] | |

| Ninpumuna | Ur, Puzrish-Dagan,[492] possibly Gishbanda[493] | Ninpumuna was the goddess of salt springs.[494] She is only attested in texts from Ur and Puzrish-Dagan from the Ur III period,[492] though it is also possible that she was worshiped in Gishbanda.[493] | |

| Ninšar Ninnisig?[495] |