The mianguan (Chinese: 冕冠; pinyin: miǎnguān; lit. 'ceremonial headdress'), also called benkan (冕冠, lit. 'ceremonial headdress') in Japan, myeonlyugwan in Korea, and Miện quan in Vietnam, is a type of crown traditionally worn by the emperors of China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, as well as other kings in the East Asia.[1]

Originating in China, the mianguan was worn by the emperor, his ministers,[2] and aristocrats.[3] The mianguan was the most expensive Chinese headware, reserved for important sacrificial events.[2] Regulations on its shape and its making were issued under the Eastern Han dynasty and applied in the succeeding dynasties only to be ended at the fall of the Ming dynasty in the 16th century AD.[2]

In Japan, the benkan has been worn by emperors since the Nara period when the Chinese-style mianguan was introduced by the Tang dynasty.[4] Emperor Shōmu was reportedly in 732 AD, during the New Year court assembly, the first emperor in Japan to fully dress into mianfu (a form of Chinese ceremonial clothing), which included the Chinese-style mianguan.[4]

It is also worn in Vietnam,[lower-alpha 1] and the monarchs of the Joseon dynasty also wore an equivalent crown, the myeonlyugwan.

Mianguan (China)

.jpg.webp)

Among all the type of Chinese headwear, the mianguan was the most expensive type; it was reserved especially for important sacrificial events.[2]

The mianguan and the mianfu were worn beginning in the Zhou dynasty, based on the ceremonial and ritual-culture of Zhou that prescribes which types of clothing and accessories could be worn by the different social ranks and during different occasions.[6] The mianfu was abolished in the Qin dynasty by the First Emperor of Qin in favour of a type of black shenyi called junxuan(袀玄) and tongtianguan instead,[7][6][8] the mianguan was however recorded.[6]

The practice of using junxuan over the mianfu was continued in the Western Han, until the Eastern Han, when Emperor Ming created new clothing regulations for ritual sacrifices and other official occasions based on Rites of Zhou and Confucian Classic of Rites, restoring the use of mianfu and mianguan.[3] The revived crown based on literature, after which it was worn in rituals and important ceremonies under several dynasties. However, the descriptions in the documents contradict one another, and each dynasty revised them often.

The basic shape of the mianguan remained the same from ancient times to the Ming dynasty. The crown worn by the Ming dynasty's Wanli Emperor has been excavated from the Dingling Mausoleum, while the painting "Illustrated Scrolls of the Emperors of the dynasties" by Yan Liben depicted emperors from the Former Han dynasty to the Sui dynasty, whose mianguan was almost the same shape as the crown depicted, with minor differences in decoration.

The mianguan of the Wanli Emperor. He is wearing the same mianguan as the mianguan in the left picture.

The mianguan of the Wanli Emperor. He is wearing the same mianguan as the mianguan in the left picture. Mianguan with nine strings, Ming dynasty

Mianguan with nine strings, Ming dynasty

Many of the non-Han Chinese dynasties that ruled China also adopted the mianguan. (Liao, which did not adopt the ritual system of the Han dynasty, and Yuan, which is considered to have a strong Mongolian flavor, also adopted the mianguan.)

The mianguan stopped being used in China since the fall of the Ming dynasty[2] and the establishment of the Qing dynasty by the Manchu. Instead, a unique Manchu crown called the 'morning crown' (mahala in Manchu) was used. The Manchu crown was shaped like an umbrella, and the top of the crown was decorated with a special pearl-encrusted ornament called the morning pearl.

Benkan (Japan)

Emperor's crown

The benkan is a type of ceremonial crown in Japan, also known as the emperor's ceremonial crown, and was once used together with kon'e (袞衣, imperial robes) in ceremonies such as accession to the throne and morning prayers.

The history book "Shoku Nihongi" (797) states, "On January 1, in the 4th year of Tenpyō, Emperor Shōmu in the Daigokuden Hall of the Imperial Palace to receive New Year's greetings from the various vassals. At this time, the Emperor put on the benpuku (冕服, lit. 'the emperor's crown and robes') for the first time."[9] Therefore, It is believed that Japanese emperors began to officially wear the benkan in 732.

In the Kojidan, it is said that "the crown at the time of the Daijosai is that of Emperor Ōjin", and that the crown of Emperor Ōjin was used at the Daijosai until the Heian and Kamakura periods. However, the crown has not survived to the present day.[10]

Among the Shōsōin treasures, there is a benkan worn by Emperor Shōmu that has been damaged and is called Onkamuri Zanketsu (御冠残欠, lit. 'remnants of the crown'). The crown does not retain its original form, but there are metal openwork pieces with phoenix, clouds and arabesque patterns, as well as pearls, coral and glass beads threaded through the crown.[11]

The benkan worn by Japanese emperors is often referred to as a "Tang-style crown", but it is actually quite different from the mianguan worn in China. The benkan worn by the emperor in the Edo period consisted of a metal frame placed on top of an openwork gilt-bronze base called the "heavenly crown", with forty-eight jewels hanging from the edge of the frame, twelve on each side.[12]

The painting Silken Painting of Emperor Go-Daigo prominently displays the benkan of Emperor Go-Daigo, which is said to be the crown of Emperor Jimmu.[13] The crown differs greatly from the Chinese crown, in that there is a bright vermillion sun decoration protruding from the front of the crown.[14] The crown has twelve tassels spread across all sides rather than merely two as in the Chinese form (six strands as only two sides of the crown are shown in the image), indicating that this is the crown used by the emperor when he is dressed in formal attire.[15]

The medieval benkan is thought to have been destroyed by fire during the Kyoto Imperial Palace fire of 1653, and new benkan was made. In the "Enthronement of Emperor Reigen and Abdication of Emperor Go-Sai" (17th century), Emperor Reigen is depicted wearing a benkan and a red kon'e, seated in a takamikura (throne). It is unusual for an emperor's face to be depicted directly on a folding screen of an accession painting.

The benkan worn by Emperor Ninkō and Emperor Kōmei during their coronation ceremonies are each preserved in the Higashiyama Gobunko (Imperial Archive) at the Kyoto Imperial Palace.[16]

The benkan was used until the coronation of Emperor Kōmei,[17] but since Emperor Meiji, the benkan has been replaced by a Go Ryūei no Kanmuri (御立纓の冠) as the government reformed the coronation to be more Shinto-based rather than Chinese inspired.[18]

View of a benkan. The actual crown of almost the same shape has been handed down to the imperial family.

View of a benkan. The actual crown of almost the same shape has been handed down to the imperial family.

Empress' crown (hokan)

The crown of an empress is called a hokan (宝冠). Whether it can be considered as a type of benkan or a different type of crown is a matter of opinion.[19]

The hokan does not have a crown board or similar metal frame on top of the crown, and there is no hair hanging from the crown board. The other difference between the hokan and the benkan is the phoenix attached to the front of the hokan. There are ornaments hanging from both ears and the beak of the phoenix, which are decorated with flowers. However, the top of the head is decorated with the same sun emblem as the benkan and the same design of Yatagarasu and Zuiun. The hokan is accompanied by a hairpin, a foreign object and a small bow.

The Order of the Precious Crown, established in 1888 (the 21st year of the Meiji) to be awarded to women, is a reference to this, and the center of the insignia is decorated with the image of a precious hokan.[19]

Miện quan (Vietnam)

The Chinese-style mianguan was also used in Vietnam, where it was known as the miện quan.[11]

Paintings of Miện quan hats in the Nguyễn dynasty

Paintings of Miện quan hats in the Nguyễn dynasty

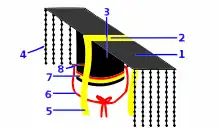

Construction and design

- Extension;

- Tianhe belt;

- Cap and roll;

- Tassels;

- Ears;

- Tail;

- Wu (武);

- Jade hairpin

The mianguan is composed of:

A long, rectangular wooden board called the mianguan board (yan in the Han dynasty)[3] was placed on top of the mianguan, with fulls hanging from the front and back of the mianguan board.

In the Han dynasty, the yan was round in the front but flat in the back; it was about 7 inches (180 mm) in width and 1 foot (0.30 m) in length.[3] On both sides of the mianguan, there was a hole where an emerald hairpin could pass through so that the crown could be fastened to the hair bun of its wearer.[3] A red band called the tianhe was attached to the centre of the mianguan and wraps around it. The silk cord was tied on one end of the hairpin and would then be tied on the other side of the hairpin passing under the chin.[3] There was also a chong er (lit. 'stuffing the ear') located on both side of the mianguan around the ear area; the chong er was a pearl or a piece of jade which symbolized that the wearer of mianguan should not believe in any slander.[3]

The number of tassels depended on the status of the wearer, and the mianguan of the emperor had 12 tassels at the front and back, for a total of 24 tassels.[20] The 12 tassels dangles down the shoulders and were made of jade beads of multiple colours which would sway with the wearer's movement.[21]

In addition, there was the nine-tasselled crown, worn by dukes and the crown prince's servants.[22][23] The eight-tasselled crown was worn by princes and dukes.[24] The qiliu mian (七旒冕, seven-tasselled crown) was worn by ministers.[25] The five-tasselled crown (wuiu mian, 五旒冕) was worn by viscounts and barons.

The quantity and quality of the jewellery were an important marker of social ranking.[3] In the Han dynasty, the emperor would use 12 strings of white jade, 7 strings of blue jade were used by dukes and princes, and black jade were used for ministers.[3]

Cultural significance

The mianguan was designed to strengthen the charismatic authority of its wearer which was conferred by the head.[21] This is similar to the Mandate of Heaven concept in which there is a rationalization of divine authority.[21]

Related items

Since China was a crown-wearing culture, there were many crowns for different ranks, positions, and times.[26]

- Feng Guan – a crown worn by an empress (e.g. Phoenix Crown – crowns of Empress Xiao Danxian and Empress Dowager Xiao Jing excavated from the Dingling site, two each)[27][28]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ The crown of the emperor during the Nguyễn dynasty is housed in the Vietnam National Museum of History.[5]

Sources

- ↑ 字通,世界大百科事典内言及, 精選版 日本国語大辞典,ブリタニカ国際大百科事典 小項目事典,デジタル大辞泉,普及版. "冕冠とは". コトバンク (in Japanese). Retrieved 2022-01-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Hua, Mei (2011). Chinese clothing (Updated ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-521-18689-6. OCLC 781020660.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 5000 years of Chinese costumes. Xun Zhou, Chunming Gao, 周汛, Shanghai Shi xi qu xue xiao. Zhongguo fu zhuang shi yan jiu zu. San Francisco, CA: China Books & Periodicals. 1987. pp. 32, 34. ISBN 0-8351-1822-3. OCLC 19814728.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - 1 2 Dorothy Ko; JaHyun Kim Haboush; Joan R. Piggott, eds. (2003). Women and Confucian cultures in premodern China, Korea, and Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-520-92782-7. OCLC 55856968.

- ↑ "Special Exhibition "The Great Vietnam Exhibition"" (in Japanese). Kyushu National Museum. Archived from the original on 2013-03-28. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

Successive Emperors of the Nguyen Dynasty wore a crown called a Benkan, which had a rectangular plate on top of its head and twelve [strings] of colorful beads lined up [on a] red string in the front and back [each].

- 1 2 3 Xie, Hong; Yan, Lan-Lan (2019). "To Explore the Changes in Dress System Affected by Imperial Politics Thinking during Sui and Tang Dynasties". Proceedings of the 4th Annual International Conference on Social Science and Contemporary Humanity Development (SSCHD 2018). Atlantis Press. pp. 26–30. doi:10.2991/sschd-18.2019.5. ISBN 978-94-6252-659-4. S2CID 159383691.

- ↑ "120". Book of Later Han.

"秦以戰國即天子位,滅去禮學,郊祀之服皆以袀玄。漢承秦故。" "顯宗遂就大業,初服旒冕,衣裳文章,赤舄絇屨,以祠天地。"

- ↑ Feng, Ge (2015). Traditional Chinese rites and rituals. Zhengming Du. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-1-4438-8783-0. OCLC 935642485.

- ↑ Saeki, Ariyoshi, ed. (1940). 六国史 [Rikkokushi] (in Japanese). Vol. 3. The Asahi Shimbun Company. p. 236. doi:10.11501/1919014.

- ↑ 源顕兼 (November 2020). 古事談. Kadokawa. ISBN 978-4-04-400557-3. OCLC 1223314021.

- 1 2 "礼服御冠残欠について―礼服御覧との関連において―" [On the Remains of the Imperial Dress and Imperial Crown: In Relation to the Imperial Dress Viewing]. Shosoin Annual Report (in Japanese). Shosoin Office, Imperial Household Agency. 17. March 1995. Archived from the original on 2022-01-18. Retrieved 2022-01-18.

- ↑ "冠とは - きもの用語大全". www.so-bien.com. Retrieved 2022-01-18.

- ↑ 内田 2006, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ 遠山 2014, p. 31.

- ↑ 黒田 1993, pp. 253–254.

- ↑ Matsudaira 2006, p. 13.

- ↑ Izutsu, Gafu (1995). "天皇の御装束" [The Ceremonial Costumes of the Emperor of Japan]. Journal of the Textile Society of Japan (in Japanese). The Textile Society of Japan. 51 (2): 78–81. doi:10.2115/fiber.51.2_P78.

- ↑ https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/25745/Miller_ku_0099D_14658_DATA_1.pdf?sequence=1 page 29

- 1 2 "Orders of the Precious Crown : Decorations and Medals in Japan - Cabinet Office Home Page". www8.cao.go.jp. Retrieved 2022-01-18.

- ↑ "周礼注疏/卷三十二 - 维基文库,自由的图书馆". zh.wikisource.org (in Simplified Chinese). Retrieved 2022-01-20.

- 1 2 3 Zhang, Fa (2016). History and spirit of chinese art. Volume 1, From prehistory to the Tang Dynasty. Honolulu: Silkroad Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-62320-126-5. OCLC 933441686.

- ↑ "32". Rites of Zhou.

诸侯之缫斿九就...每缫九成,则九旒也。

- ↑ "25". Book of Jin.

皇太子...其侍祀则平冕九旒

- ↑ "25". Book of Jin.

王公八旒。

- ↑ "25". Book of Jin.

卿七旒。

- ↑ Han, Myun-Sook; Im, Sung-Kyung (2005). "A Study on the Artificial Flowers as a Hair Ornament in China" (PDF). Proceedings of the Costume Culture Conference (복식문화학회:학술대회논문집). The Costume Culture Association: 67–69.

- ↑ Yang, Shaorong (2004). Traditional Chinese clothing: costumes, adornments & culture. San Francisco: Long River Press. ISBN 978-1-59265-019-4. OCLC 52775158.

- ↑ Press, Beijing Foreign Language (2012-09-01). Chinese Auspicious Culture. Asiapac Books Pte Ltd. ISBN 978-981-229-642-9.

Bibliography

- Matsudaira, Norimasa (2006). 図説宮中柳営の秘宝 [Illustrated: Treasures of the Imperial Family and the Shoguns] (in Japanese). Kawade Shobō Shinsha. ISBN 978-4309760810.

- 閻歩克『服周之冕』中華書局、2009年。

- Abe, Yasuro (2013). 中世日本の宗教テクスト体系 [Medieval Japanese Religious Textual Systems]. Nagoya University Press. ISBN 978-4815807238.

- 内田, 啓一 (2006), 文観房弘真と美術, 法藏館, ISBN 978-4831876393

- 黒田, 日出男 (1993), 王の身体 王の肖像, イメージ・リーディング叢書, 平凡社, ISBN 978-4582284706

- 遠山, 元浩 (2014). 清浄光寺蔵「後醍醐天皇像」関連史料の一考察. 駒沢女子大学研究紀要 (in Japanese). 出版社不明. 21 (21): 27–44. doi:10.18998/00001184.