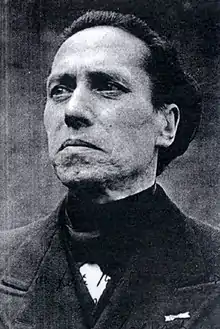

Michel de Ghelderode | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Adhémar-Adolphe-Louis Martens 3 April 1898 |

| Died | 1 April 1962 (aged 63) Brussels, Belgium |

| Nationality | Belgian |

| Other names | Philostene Costenoble Jac Nolan Babylas |

| Occupation | dramatist |

| Spouse | Jeanne-Françoise Gérard (d.1980) |

Michel de Ghelderode (born Adémar Adolphe Louis Martens; 3 April 1898 – 1 April 1962) was an avant-garde Belgian dramatist, from Flanders, who spoke and wrote in French. His works often dealt with the extremes of human experience, from death and degradation to religious exaltation. He wrote plays and short stories, and was a noted letter writer.[1]

Personal life

Michel de Ghelderode was born in Brussels, Belgium in 1898.[2] Ghelderode's father, Henri-Louis Martens, was employed as a royal archivist, a line of work later to be pursued by young Ghelderode. The author's mother, née Jeanne-Marie Rans, was a former postulant for holy orders; even after bearing four children, of whom Ghelderode was the youngest. She retained evident traces of her erstwhile vocation that would strongly influence the mature Ghelderode's dramatic work: One of Mme Martens's remembered "spiritual tales," concerning a child mistakenly buried alive who remained strangely marked by death even after her rescue, inspired most of the plot and characters of Ghelderode's Mademoiselle Jaire (1934) written when the author was in his mid-thirties.

He also served in the military from 1919 – 1921, and in 1924 married Jeanne-Françoise Gérard (d. 1980).

Ghelderode became increasingly reclusive from 1930 onwards and was chronically ill with asthma during his late thirties. Frequently suffering from poor health, around the age of sixteen, while pursuing his studies at the Institut St.-Louis in Brussels, he fell gravely ill with typhus. He would retain for the rest of his life the vision of "a Lady" who materialized at his bedside to utter the words; "not now, sixty-three." Ghelderode in fact died two days short of what would have been his sixty-fourth birthday in 1962. He is buried in the Laeken Cemetery, Brussels.

Influences

.jpg.webp)

Ghelderode's ideas and vision of the theatre is in remarkable accord with ideas Antonin Artaud expressed in his manifesto The Theatre and Its Double, which was originally published 1 February 1938.[3] Both men saw theatre as having the potential to express the human unconscious with its dream-like hallucinatory images and dynamic appetites. And both Artaud and Ghelderode found inspiration in the fantastical, dream-like images and ideas found in the works of the Flemish painters Bosch and Brueghel.[4] Ghelderode referred to Brueghel as his "père nourricier" (foster father), wrote plays closely based on Brueghel's paintings,[5] and said of Brueghel's "Dulle Griet" that it "was not only a wonderful painting but offered a vision of the world, a philosophy."[6] Artaud independently discusses in detail the very same painting (Brueghel's "Dulle Griet") in The Theatre and Its Double to illustrate his own ideas regarding the theatre of cruelty, as he references the "nightmares of Flemish painting".[7]

Ghelderode, who was born in Flanders, expressed a great appreciation for Flemish folk traditions and culture, which permeates his plays and stories.[8] Ghelderode has said, "The Fleming lives in a hallucinatory world…. But our eye remains meticulously realistic; the keen awareness of the surface and of the great mysteries beyond – there you have the Fleming since even before Brueghel. … The ridiculous outside and the wretched, sublime eternal quandary of the soul … I am not a revolutionary; I am merely writing in the tradition of my race."[9]

Ghelderode's influences include puppet theater, Italian commedia dell'arte, the medieval world of Flanders, the Flemish painters Bosch, Bruegel, Jacob Jordaens and the Teniers, along with the Belgian artist James Ensor, painter of the macabre, and the novelist Georges Eekhoud.

A number of Ghelderode's plays are based on the paintings by Breughel. His play The Blind Men (Les Aveugles, 1933) is derived from Brueghel's The Parable of the Blind, The Magpie on the Gallows (La Pie sur le Gibet, 1935) is derived from Breughel's The Merry Way to the Gallows, and The Strange Rider (Le Cavalier Bizarre, 1920) is not based on a particular painting, but, as the preface states, it is inspired by Breugel.[10]

Career

A prolific writer, Ghelderode wrote more than 60 plays, a hundred stories, a number of articles on art and folklore and more than 20,000 letters.

He began writing plays in French in 1916. La mort regarde à la fenêtre (Death Looks in at the Window) was produced in 1918, followed by Le repas des fauves (The Beasts' Meal) in 1919. In 1921 and 1922 he was a professor at the Institut Dupuich but resigned because of ill health. The following year he worked as a bookseller. In 1923 Ghelderode earned the post of archives editor in the Communale de Schaerbeek, where he worked in a variety of capacities until 1945. In 1924 he began contributing to such publications as La Flandre littéraire and La Renaissance d'Occident and wrote plays for the puppet theater Les Marionnettes de la Renaissance d'Occident. Ghelderode began staging plays again in 1925, working with the Dutch producer Johan de Meester, a collaboration which lasted until 1930. Escurial (1927) is one of his most frequently performed plays. Widely recognized as one of his finest achievements, it exhibits German Expressionism and Symbolist influences. He wrote Pantagleize (1929) expressly for the Flemish comedian Renaat Verheyen, who died aged twenty-six, shortly after appearing in the title role.

Ghelderode completely gave up writing plays in 1939. Between 1946 and 1953 he wrote for Le Journal de Bruges.In Paris during 1949, productions of Ghederode's plays, especially Fastes d'enfer (Chronicles of Hell), caused huge uproar. Some theatre-goers were excited and some were furious. It achieved for Ghelderode a succès de scandal.[11]

Themes and style

Ghelderode is the creator of a fantastic and disturbing, often macabre, grotesque and cruel world filled with mannequins, puppets, devils, masks, skeletons, religious paraphernalia, and mysterious old women. His works create an eerie and unsettling atmosphere although they rarely contain anything explicitly scary.

A strong anticlerical streak runs through many of Ghelderode's plays, mitigated by a spirituality which stops short of true belief. Throughout Ghelderode's theatrical universe, religion is more often honored than adhered to. Sensuality is another dominant characteristic prominent in almost all of Ghelderode's plays, often in unattractive forms. Gluttony and heavy drinking loom large, as does lust, often represented by hag-like female characters with suggestive names.

According to Oscar G. Brockett, Ghelderode's works resemble those of Alfred Jarry, the surrealists and the expressionists, and his theories are similar to those of Antonin Artaud. Through nearly all of his plays runs his perception of human beings as creatures whose flesh overpowers spirit. "Corruption, death and cruelty are always near the surface [of Ghelderode's work], although behind them lurks an implied criticism of degradation and materialism and a call to repentance."[12]

Ghelderode was one of the first dramatists to exploit the idea of total theatre—that is, drama in which every sort of appeal is made to the eye, the ear, and the emotions in order to stir the intellect. As a pioneer of total theatre, Ghelderode exerted a powerful influence on the history of the French theatre. Although many of his plays have since been translated into English, his works are infrequently performed in English-speaking countries. Writing in October 1957 on the occasion of the first of his plays to be seen publicly in England, Ghelderode declared –

The moral of this sad story – and the story of man is always sad, absurd, and void of meaning, as Shakespeare wrote – it is that in our atomic and auto-disintegrated age, this age from which dreams and dreamers are banished in favor of the scientific nightmare and the beneficiaries of the future horror, a fellow like Pantagleize remains an archetype, an exemplary man and a fine example who has nothing to do with that dangerous thing, intelligence, and a great deal to do with that savior, instinct. He is human in an age when all is becoming dehumanized. He is the last poet, and the poet is he who believes in heavenly voices, in revelation, in our divine origin. He is the man who has kept the treasure of his childhood in his heart, and who passes through all catastrophes in all artlessness. He is bound by purity to Parsifal and to Don Quixote by courage and holy madness. and if he dies, it is because particularly in our time, the Innocents must be slaughtered: that has been the law since the time of Jesus. Amen !....[13]

In 1957, Luc de Heusch and Jean Raine made a 22-minute film about Ghelderode. He appears near its end, in the location of the Royal Theatre Toone, the sixth and last in a dynasty of marionette theatres in Brussels.

Pseudonyms

Ghelderode was born with the name Adhémar-Adolphe-Louis Martens, and changed his name by Royal Deed. He also wrote under the pen-names Philostene Costenoble, Jac Nolan, and Babylas.

Adaptations

Ghelderode's La Balade du Grand Macabre (1934) served as libretto for György Ligeti's opera Le Grand Macabre (1974–77. Revised 1996).

Works

Plays

- La Mort regarde à la fenêtre (Death Looks in the Window) (1918)

- Le repas des fauves (The Beasts' Meal) (1918)

- Piet Bouteille (or Oude Piet) (1920) Produced Brussels, Théâtre Royal du Pare, 2 Apr. 1931

- Le Cavalier bizarre (The Strange Rider) (1920 or 1924)

- Têtes de bois (Blockheads) (1924)

- Le Miracle dans le faubourg (Miracle in the Suburb) (1924, unedited)

- La Farce de la Mort qui faillit trépasser (The Farce of Death Who Almost Died) (1925) Produced Brussels, Vlaamse Volkstoneel, 19 Nov. 1925

- Les Vieillards (The Old Men) (1925)

- La Mort du Docteur Faust (1926) Produced Paris, Théâtre Art et Action, 27 Jan. 1928

- Images de la vie de saint François d'Assise (1926) Produced Brussels, Vlaamse Volkstoneel, 2 Feb. 1927

- Venus (1927)

- Escurial (1927) Produced Brussels, Théâtre Flamand, 12 Jan. 1929.

- Christophe Colomb (1927) Produced Paris, Théâtre Art et Action, 25 Oct. 1929

- La Transfiguration dans le Cirque (The Transfiguration at the Circus) (1927)

- Noyade des songes (Dreams Drowning) (1928)

- Un soir de pitié (A Night of Pity) (1928)

- Trois acteurs, un drame... (1928) Produced Brussels, Théâtre Royal du Parc, 2 Apr. 1931

- Don Juan (1928)

- Barabbas (1928) Produced Brussels, Vlaamse Volkstoneel, 21 Mar. 1928; and Brussels, Théâtre Résidence, 8 Jan. 1934

- Fastes d'enfer (Chronicles of Hell) (1929) Produced Paris, Théâtre de l'Atelier, 11 July 1949

- Pantagleize (1929) Produced Brussels, Vlaamse Volkstoneel, 24 April 1930; and Brussels, Théâtre Royal du Parc, 25 October 1934

- Atlantique (1930)

- Celui qui vendait de la corde de pendu (The One Who Sold the Hanging Rope) Farce in three acts (1930)

- Godelieve (1930, unedited) Produced Ostend 1932

- Le Ménage de Caroline (Caroline's Household) (1930) Produced Brussels, Théâtre de l'Exposition, 26 Oct. 1935

- Le Sommeil de la raison (The Sleep of Reason) (1930) Produced Oudenaarde, 23 Dec. 1934

- Le Club des menteurs (ou Le Club des mensonges) (Liar's Club) (1931)

- La Couronne de fer-blanc (The Tin-Plated Crown) Farce, two acts and three tableaux. (1931)

- Magie rouge (Red Magic) (1931) Produced Brussels, Estaminet Barcelone, 30 Apr. 1934

- Les Aveugles (1933) (The Blind Men) Produced Paris, Théätre de Poche, 5 July 1956

- Le Voleur d'étoiles (The Star Thief) (1931) Produced Brussels, Vlaamse Volkstoneel, 7 Apr. 1932

- Le Chagrin d'Hamlet (The Sorrow of Hamlet) (1932)

- Vie publique de Pantagleize 1932(?)

- La Grande Tentation de Saint Antoine (The Great Temptation of Saint Anthony). Burlesque cantata (1932)

- Pike anatomique (Anatomical Play) (1932)

- Le marchand de reliques (The Relic Dealer) Pseudodrama (1932)

- Casimir de l'Academie... (Casimir of the Academy) Pseudodrama (1932)

- Paradis presque perdu (Paradise Almost Lost) Mystery. (1932)

- Genéalogie (Genealogy) Pseudodrama (1932)

- Arc-en-ciel (Rainbow) (1933)

- Les Aveugles (The Blind men) (1933)

- Le Siège d'Ostende (1933)

- Swane A Forest Legend, Opera (1933) to a story by Stijn Streuvels, music by Maurice Schoemaker

- Plaisir d'amour (1933)

- Le Soleil se couche (1933) (The Sun Sets) Produced Brussels, Théâtre Royal Flamand, 23 Jan. 1951

- Adrian et Jusemina (1934) Produced Brussels, Théâtre Residence, 19 Jan. 1952

- Le Perroquet de Charles Quint (The Parrot of Charles V) (1934)

- Masques ostendais (1934)

- Petit drame (1934)

- La Balade du Grand Macabre (1934) Produced Paris, Studio des Champs-Élysées, 30 Oct. 1953

- Sire Halewyn (1934) Produced Brussels, Théâtre Communal, 21 Jan. 1938

- Mademoiselle Jaïre (1934)

- Le Soleil se couche... (The Sun Goes Down) (1934)

- Hop Signor! (1935)

- Sortie de l'acteur (Exit the Actor) (1935)

- Le Vieux Soudard (The Old Trooper) Cantata (1935)

- Le singulier trépas de Messire Ulenspigel (The Singular Death of Messire Ulenspigel) Play, eight scenes (1935)

- La Farce des Ténébreux (The Farce of Shadows) (1936)

- La Pie sur le gibet (The Magpie on the Gallows) (1937)

- Pantagleize est un ange (Pantagleize is an Angel) (1938, draft)

- La Petite Fille aux mains de bois (The Little Girl with Wooden Hands) (with Jean Barleig). Fairy Tale, three acts. (1939)

- Scenes from the life of a Bohemian: Franz Schubert (1941)

- L'École des bouffons (School for Buffons) (1942)

- La Légende de la Sacristine (The Legend of the Sacristan) (1942, draft)

- Le Papegay triomphant (1943, unedited)

- For They Know Not What They Do (1950, unedited)

- La folie d'Hugo van der Goes (The Madness of Hugo van der Goes) Play, three scenes (1951)

- Marie la misérable (1952)

- The Touching and Very Moral Heavenly Tribulation ... (full title: The Touching and Very Moral Heavenly Tribulation of Petrus in Eremo, pastor of a lean parish to the fat land of Flanders), (1960, unfinished)

- Angelic Chorus (1962, unedited)

Plays for marionettes

- Le Mystère de la Passion de Notre-Seigneur Jésus Christ (1924, for marionettes) Produced Brussels,

- Théâtre des Marionnettes de Toone, 30 Mar. 1934.

- Le Massacre des Innocents (1926, for marionettes)

- Duvelor ou la Farce du diable vieux (Duvelor, or the Farce of the Old Devil) (1925, for marionettes)

- La ronde de nuit (The Night Watch). Pseudodrama for marionettes. (1932)

- La nuit de mai (The Night in May). Drama for marionettes. (1932)

- Les Femmes au tombeau (The Women at the Tomb) (1933, for marionettes)

- D'un diable qui prêcha merveilles (Of a Devil Who Preached Wonders) Mystery for marionettes, 3 acts. (1934)

Poetry

- La Corne d'Abondance (The Horn of Abundance) (1925)

Prose

- Voyage Autour de ma Flandre (or Kwiebe-Kwiebus) (1921)

- L'Histoire Comique de Keizer Karel (1922)

- La Halte catholique (1922)

- L'Homme sous l'uniforme (The Man under the Uniform) (1923)

- L'Homme à la moustache d'or (The Man with the Mustache of Gold) (1931)

- Sortilèges (Spells) (1941)

- Mes Statues (1943)

- Choses et gens de chez nous (Things and People from Home) (1943, 2 volumes)

- La Flandre est un songe (1953)

- The Ostend Interviews (1956)

Sources

- George Hauger (1960) Introduction and trans. Seven Plays (The Women at the Tomb, Barabbas, Three Actors and Their Drama, Pantagleize, The Blind Men, Chronicles of Hell, Lord Halewyn and The Ostend Interviews) MacGibbon & Kee

- Parsell, David B. (1993) Michel de Ghelderode. New York: Twayne Publishers. 0-8057-43030

- Ghelderode, Michel de (edited by R. Beyen) (1991–1962) Correspondance de Michel de Ghelderode. Bruxelles: Archives du Futur (Tomes 1–10)[14]

- To Directors and Actors: Letters, 1948-1959[15]

- Willinger, David (2000) Ghelderode. Austin, TX: Host Publishers including translations into English of the plays: 'The Siege of Ostend,' 'Transfiguration in the Circus,' and 'The Actor Makes His Exit'

- Willinger, David (2002) Theatrical Gestures of Belgian Modernism. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc. 0-8204-5503-2, including translations into English of the plays: Venus, Dreams Drowning, and Blockheads.

References

- ↑ Bédé, Jean Albert. Edgerton, William Benbow. "Ghelderode, Michel de". Columbia Dictionary of Modern European Literature. Columbia University Press (1980) pp. 302-303. ISBN 9780231037174

- ↑ Ghederode, Michel de. Ghelderode Seven Plays. Hill and Wang. 1960. p. viii.

- ↑ Esslin, Martin (1 January 2018). Antonin Artaud. Alma Books. p. 51. ISBN 9780714545622

- ↑ Hellman, Helen. "Hallucination and Cruelty in Artaud and Ghelderode". The French Review. Vol. 41, No. 1 (Oct., 1967), pp. 1-10.

- ↑ Hauger, George. Ghelderode, Michel de. "The Ostend Interviews". Tulane Drama Review (1959). Vol. 3, No. 3 (Mar., 1959), pp. 3-23

- ↑ Hauger, George. Ghelderode, Michel de. "The Ostend Interviews". Tulane Drama Review (1959). Vol. 3, No. 3 (Mar., 1959), p. 15

- ↑ Artaud, Antonin. The Theater and Its Double. Grove Press (1994)ISBN 978-0802150301 pp. 71 & 102

- ↑ Hellman, Helen. "Hallucination and Cruelty in Artaud and Ghelderode". The French Review. Vol. 41, No. 1 (Oct., 1967), pp. 1-10.

- ↑ Hellman, Helen. "Hallucination and Cruelty in Artaud and Ghelderode". The French Review. Vol. 41, No. 1 (Oct., 1967), pp. 1-10.

- ↑ Wellwarth, George I. "Ghelderode's Theatre of the Grotesque". The Tulane Drama Review, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Autumn, 1963), p. 15

- ↑ Ghederode, Michel de. Ghelderode Seven Plays. Hill and Wang. 1960. pp. vii & ix.

- ↑ Brockett, Oscar Gross, History of the Theatre, Oscar G. Brockett, Franklin J. Hildy. 9th ed. 2003, Pearson Education Group, Inc.

- ↑ Seven Plays including Pantagleize, translated and with an Introduction by George Hauger. MacGibbon & Kee 1960

- ↑ Ghelderode, Michel de. Correspondance de Michel de Ghelderode. Series: Archives du futur (French Edition) Publisher: Editions Labor (1991). ISBN 9782804008154

- ↑ Ghelderode, Michel de. Knapp, Bettina, translator. To Directors and Actors: Letters, 1948-1959. The Tulane Drama Review. Vol. 9, No. 4 (Summer, 1965), pp. 41-62

External links

- "The Black Diamond" (in French)

- Michel de Ghelderode at the Internet Broadway Database