Mieczysław Weinberg | |

|---|---|

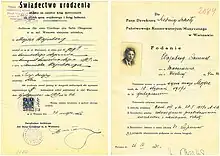

Pencil portrait of Weinberg, January 1949 | |

| Born | Mojsze Wajnberg December 8, 1919[note 1] Warsaw, Poland |

| Died | February 26, 1996 (aged 76) Moscow, Russia |

| Resting place | Domodedovo Cemetery |

| Nationality | Polish, Soviet, Russian |

| Other names | Moisei Vainberg |

| Notable work | List of compositions by Mieczyslaw Weinberg |

| Spouses | Natalya Mikhoels

(m. 1942; div. 1970)Olga Rakhalskaya (m. 1970) |

| Children | 2 |

| Parents |

|

Mieczysław Weinberg (December 8, 1919[note 1] – February 26, 1996) was a Polish and Soviet composer and pianist. His compositions include 22 symphonies, a host of chamber works (including 17 string quartets as well as sonatas for violin, cello, and piano), a violin concerto, and seven operas. He was a contemporary of Dmitri Shostakovich, and they often shared ideas with each other. A 2004 reviewer considered him as "the third great Soviet composer, along with Prokofiev and Shostakovich".[1] A 2017 article in the New York Times noted that his "darkly lucid music is beginning to gain wider recognition."[2]

Spelling and transliteration of name

Weinberg's name was registered on his birth certificate as Mojsze Wajnberg. Throughout his adult life, he signed his letters in Polish using the Polish spelling of his surname.[3] During his career in the Yiddish theater of interwar Warsaw, he was known by the German spelling of his name, Mosze Weinberg (Yiddish: משה װײַנבערג); a typical convention of the time for Polish musicians who aspired to produce recordings for export.[4][5] Weinberg adopted the given name Mieczysław professionally at the beginning of his musical career because he believed it sounded more Polish and prestigious.[6]

In the Soviet Union, he was officially known as Moisey Samuilovich Vaynberg (Russian: Моисей Самуилович Вайнберг). [7] The name was the result of legal expediency and his personal indifference when he sought refuge in the Soviet Union in 1939. Years later, he recalled waiting to cross over from the Polish border:

Some kind of troop was organized to examine the documents, but it was done rather carelessly, because there were so many people around. I was asked: "Family name?"—"Weinberg"—"First name?"—"Mieczysław"—"Mieczysław, what's that? Are you Jewish?"—"Yes, Jewish"—"Then 'Moisey' it is".[7]

In the 1980s, he successfully petitioned to have his name changed back to Mieczysław.[8] Among friends in Russia, he would also go by his Polish diminutive "Mietek".[9]

Re-transliteration of the composer's surname from Cyrillic back into the Latin alphabet produces a variety of spellings. "Vainberg" became the most common in the 1990s because of a series of compact disc releases on the Olympia label. Per Skans, the author of their liner notes, had erroneously believed that this was the composer's favored choice. Starting in the 21st century, "Weinberg" became the most widespread spelling. The composer himself never declared a preference.[10]

Biography

Youth

Weinberg was born in Warsaw on December 8, 1919.[11][note 1] His father, Szmuel,[13] was a well-known conductor, composer,[9][14] and violinist at the Jewish Theatre in Warsaw.[15] He had originally come from Kishinev, Bessarabia Governorate (today part of Moldova), which he left shortly before Kishinev pogrom of 1903, in the course of which Weinberg's grandparents and great-grandparents were killed.[16] Weinberg's mother, Sara (née Sura Dwojra Sztern or Sara Deborah Stern),[note 2] was Szmuel's second wife.[17] She had been born in Odessa, Kherson Governorate (today part of Ukraine), and was an actress in several Yiddish theater companies in Warsaw and Łódź.[18] One of the composer's cousins, Isay Abramovich Mishne, was the secretary of the Military Revolutionary Committee of the 1918 Baku Commune. He was executed in 1918 along with the other 26 Baku Commissars.[19]

The Weinberg's family home was located in the Wola district, on Krochmalna Street.[20] From an early age, Weinberg was surrounded by music; he later told his second wife that "life was my first music teacher". At the age of six, he began to accompany his father to musical performances. At an early age, he taught himself to play the piano, eventually developing enough skill to substitute for his father as conductor. He also began to compose, although he did not accord these early works importance:[21]

What does writing music mean to a child? I simply took down one of my father's music sheets and scribbled down something or other... But in this way, I studied music right from my birth, as it were. And when I wrote these "operettas" I probably imagined myself to be a composer.[21]

At the age of 12, Weinberg began his first formal music lessons at a school in Warsaw. Discerning his precocity, his teacher enrolled him at the Warsaw Conservatory in October 1931, where she felt his talent would be better fostered. Who Weinberg's teachers were in the first two years at the conservatory are no longer known, but in 1933 he became a student of Józef Turczyński,[22] who considered Weinberg to be one of his best students along with Witold Małcużyński.[21] Weinberg graduated in 1939.[23]

Little is known about the influences and musical activities Weinberg may have experienced in Poland.[24] He made his professional debut in a chamber concert organized by the Polish Society for Contemorary Music on 10 December 1936, wherein he was the pianist for the world premiere of Andrzej Panufnik's Piano Trio. His next appearance was in mid-1937, where he was one of the musicians that performed at the conservatory's annual graduation concert. The students receiving diplomas at the event included Witold Lutosławski, Stefan Kisielewski, and Zbigniew Turski. The latter's Piano Concerto was included on the concert program; Weinberg was the soloist. A reviewer praised him as the best performer at the concert and described his playing as "truly masculine".[4]

Weinberg's compositions from this period consisted of a pair of mazurkas, Three Pieces for violin and piano, and his String Quartet No. 1; the latter was dedicated to Turczyński. In 1936, Weinberg also contributed music to an early film by Zbigniew Ziembiński, Fredek uszczęśliwia świat,[25] in which he made a brief appearance playing the piano.[26] The film also included songs by his father, who may have conducted the ensemble used for the film.[27]

In May 1938, Weinberg was introduced by Turczyński to his friend, the pianist Josef Hofmann, who held the post of honorary professor at the conservatory and who was then touring Poland. Weinberg played for him Johann Sebastian Bach's Italian Concerto and Mily Balakirev's Islamey. Impressed, Hofmann invited Weinberg to become his student at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, for which he promised to procure an American visa.[28] Ultimately, Weinberg decided to pursue a career as a composer rather than pianist. In the event, he was unable to accept Hofmann's offer because of the invasion of Poland in 1939;[29] Weinberg referred to this as having marked the end of "the best and happiest period" of his life.[30]

Escape from Poland

Despite the outbreak of war, Weinberg maintained his daily routine; he believed the assurances of Polish propaganda that Poland was emerging victorious against Germany's invasion. Late on the night of September 6, 1939, Weinberg returned home from the Café Adria, where he worked as a pianist. As he ate a meal that his mother had prepared for him, he heard a radio announcement urging all citizens of Warsaw to flee as the arrival of the German Army was imminent. The next morning, Weinberg left heading eastwards with his younger sister, but she decided to return home because her shoes were badly hurting her feet.[31] Weinberg never saw his sister and parents again.[15][32] It was not until 1966, when he returned to Poland for a visit, that he learned from surviving former neighbors that his family had been murdered at the Trawniki concentration camp.[32]

For seventeen days Weinberg headed alone to the Soviet border, eating little, and avoiding gunfire and bombings. Along the way, he witnessed the deaths of several other refugees who were traveling with him.[31] One of the incidents occurred near the Soviet–Polish border:[33]

Two or three Jews were walking along the road; their clothing revealed that they were Jews. In that moment, a motorcycle came along. A German got off and, from the gesticulation, we understood that he was asking for the way somewhere. They showed him precisely... He probably said "Danke schön", sat down again, started the engine, and as the Jews resumed walking, to send them on their way he threw a hand grenade, which tore them to shreds. I could have easily died the same way. On the whole, dying was easy.[33]

On 3 October, Weinberg arrived at the border. He recalled that he and other refugees were grateful to have made it and that they "blessed the Red Army which could save [them] from death".[33] After crossing the border, Weinberg traveled to Minsk in the Byelorussian SSR. His poor health precluded him from consideration for military service.[7] He arrived with little else aside from some of his musical manuscripts and family photographs.[34]

Refugee in the Soviet Union

After crossing into the Soviet Union, it is believed that Weinberg first journeyed through Brest, then Pinsk, and Luninets; at the latter he composed his Piano Sonata No. 1, which he nicknamed after the town. He finally arrived in Minsk, where he and other recent immigrants from Poland were granted Soviet citizenship by local authorities. This permitted him the privilege of enrolling for studies at the Minsk Conservatory and became one of the students in Vasily Zolotarev's composition class.[34] In addition, Weinberg also took courses in counterpoint, music history, harmony, orchestration, and conducting.[35] His classmates included Eta Tyrmand, Genrikh Wagner, and Ryszard Sielicki. According to Lev Abeliovich, Weinberg was considered the best student.[36] He settled into a room at the conservatory's dormitory. His roommate was Alexei Klumov, a pianist and former student of Heinrich Neuhaus. Klumov taught Russian to Weinberg, who quickly became fluent in the language.[37] After school, Weinberg continued playing the piano to earn money. He sometimes was a duet partner for Tyrmand, with whom he played medleys of themes from popular American films.[38]

Zolotarev had been taught composition by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and, through him, inherited the traditions of the Mighty Handful, particularly their use of folk music idioms. In turn, Weinberg absorbed these influences and began turning to Jewish folklore and music for inspiration.[39] Pleased at the young man's abilities, Zolotarev described Weinberg as "a charming and handsome young man, very (extraordinarily) talented". Concern for Weinberg's health and financial well-being led Zolotarev to solicit help for him from the Committee on the Arts. This led to Weinberg being sent to Moscow as one of the participating delegates for the Festival of Byelorussian Art in June 1940. Through Klumov, Weinberg met Nikolai Myaskovsky:[40]

I remember how baffled I was and it impressed me for my entire life when I saw [Myaskovsky] for the first time: I was twenty years old and he was already over fifty, I think; to me he seemed like an old man. When I was preparing to leave, he suddenly began to help me putting on my coat. I was shocked and my hands started trembling: "Oh, but please, please!"[41]

.jpg.webp)

While resident in Minsk, Weinberg composed several works. These include his Piano Sonata No. 2; Acacias, his first song cycle, with texts by Julian Tuwim; and his Symphonic Poem. Weinberg said that Acacias was meant to be a distraction from wartime stresses; it is dedicated to an unnamed woman in whom the composer presumably had a romantic interest. The Symphonic Poem had initially been named the Chromatic Symphony. It was premiered on June 21, 1941 by the State Symphony Orchestra of the Byelorussian SSR conducted by Ilya Musin.[42] Weinberg also first experienced what he later likened to as "the discovery of a continent": the music of Dmitri Shostakovich.[41] This first occurred during a performance by the State Symphony Orchestra of the Byelorussian SSR of the latter's Symphony No. 5. At the time, the orchestra lacked a harp and celesta; Weinberg played their parts on the piano:[43]

And so this was the first time I found out any music by [Shostakovich]... I understood that being just any composer was for more or less talented craftsmen, but a real composer was a reasoning and comprehending personality. I remember how, sitting and playing in the orchestra, I was amazed by every phrase, every musical idea, as if a thousand electrical charges were piercing me. Probably this is the feeling felt by everyone who at one time or another has felt the urge to exclaim "Eureka!"[44]

Aside from the Three Fantastic Dances, Weinberg had little familiarity with Shostakovich; a fact he expressed regret for later in life. "Even today I feel aggrieved because I was deprived of [Shostakovich's] music in the strongest, freshest years of my youth", he said.[41]

On June 22, 1941, the Germans began their invasion of the Soviet Union. All men were ordered to report to local military offices for duty. Weinberg was again exempted from military service, with his Pott's disease cited as the reason. On July 23, he received his diploma from the conservatory; it was signed by Vissarion Shebalin, the chairman of the Moscow branch of the Union of Soviet Composers. Along with his diploma, Weinberg gathered his manuscripts and family photographs, then fled Minsk with his friend Klumov.[45] Although Weinberg was initially refused permission to leave by the authorities, he obtained forged documents that certified him as a music teacher from Klumov. With these he was able to travel as far as his finances permitted, to Tashkent in the Uzbek SSR. Most of the State Symphony Orchestra of the Byelorussian SSR musicians who had not been able to leave Minsk were killed in the subsequent German bombing and capture of the city.[46]

Tashkent

Circumstances in Tashkent during the Great Patriotic War were difficult. The first wave of refugees who arrived in the city found plenteous food and places to live.[47] This gave rise to a popular saying at the time, "Tashkent has bread in abundance".[48] As the war progressed, however, nationwide supply shortages and continuing influxes of evacuees strained the city's resources. Housing and food became scarce; crime rates soared. It was not uncommon to see people dying in the street from starvation.[47]

Nevertheless, when Weinberg and Klumov disembarked in Taskent in July 1941, they were determined to secure employment and ration cards for themselves. With his skills as a piano soloist and ensemble player, as well as composer, Weinberg was in an advantageous position. He was quickly hired by the Uzbek SSR State Opera and Ballet Theatre as a tutor and répétiteur.[49] Later, through his friendship with the Uzbek composer Tokhtasyn Dzhalilov,[50] Weinberg was engaged to work jointly with Klumov and four other Uzbek composers on the creation of The Sword of Uzbekistan, a socialist realist opera with Uzbek folk music themes. They counted among their collaborators Mutal Burhonov, who in 1947 composed the "Anthem of the Uzbek SSR" (later adapted as the "State Anthem of Uzbekistan").[49] The opera, whose plot combined Uzbek national myths that were modified to support the Soviet war effort, has since been lost.[51]

On August 4, 1941, while work proceeded on the opera, Weinberg attended a party hosted by Flora Syrkina, the second wife of the artist Alexander Tyshler. It was there that Weinberg met Natalya Mikhoels, the daughter of Solomon Mikhoels, the actor and director of GOSET. Weinberg's relationship with Natalya led to marriage in 1942.[49] They moved into a dormitory on the campus of Academy of Sciences of the Uzbek SSR, which they shared with Mikhoels and his wife. Weinberg's marriage into the family of Mikhoels, who was then at the peak of his career as leader of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, significantly improved the composer's social and financial standing.[52] He intensely admired and respected his father-in-law, to whom he dedicated his Violin Sonata No. 1 composed in 1943.[53] In turn, Mikhoels strove to find any information for Weinberg about the fate of his family, but was unsuccessful. It was only through a meeting with the trumpeter Eddie Rosner, a fellow emigrant from Poland who was touring Tashkent and had also played at the Café Adria before the war, that he learned his family had been deported from Warsaw by train to an unknown destination. This would be all Weinberg knew about his family until 1966.[54]

In Tashkent, Weinberg developed his skills as a composer and wrote music prolifically. Aside from the Violin Sonata No. 1, he composed his Piano Sonata No. 2, which was premiered in Moscow by Emil Gilels, whom he had met in Tashkent. Two pieces for string quartet, the "Aria" and "Capriccio", were also composed, but these remained unperformed during the composer's lifetime.[52] In addition, he also composed his Children's Songs for voice and piano, based on texts by I. L. Peretz; they were the first of his compositions to be published.[55]

Most important of Weinberg's works composed in Tashkent was his Symphony No. 1, written in late 1942 and dedicated to the Red Army. Despite being unperformed until 1967, the work was of decisive importance in Weinberg's life. Around the time of the symphony's composition, the faculty of the Leningrad Conservatory was evacuated to Tashkent. Israel Finkelstein, a former teaching assistant to Shostakovich, met Weinberg and was greatly impressed by his music. Afterwards, Finkelstein conveyed his opinions on Weinberg to Shostakovich. His enthusiasm provoked Shostakovich's curiosity, who requested to see some of Weinberg's scores. Another member of the conservatory staff, Yuri Levitin, a former Shostakovich pupil, was also befriended by Weinberg in Tashkent; Weinberg had consigned to him a copy of his Symphony No. 1 to give to Shostakovich.[55] Weinberg may have also been assisted by Mikhoels, who had a friendly relationship with the composer. A few weeks later, Weinberg received an official invitation from the Committee on the Arts to come to Moscow.[56]

Wartime success

Weinberg and his family arrived in Moscow in late summer 1943. They briefly settled into an apartment on Tverskoy Boulevard, where his father-in-law Mikhoels had lived prior to the war, before moving into another home on Nikitsky Boulevard. On October 3, the couple's only child, Victoria, was born;[57] her name was chosen to represent their hope for a Soviet triumph in the war.[52] In September, Weinberg's Symphony No. 1 had been performed for the Union of Soviet Composers. Myaskovsky was among those who heard the work; he described it as "talented, technically fine, but without warmth".[57]

According to Weinberg's later reminiscences, he first met Shostakovich in person in October 1943. He was received at the latter's apartment located on Myasnitskaya Street. Waiting with Shostakovich was his friend, the musicologist and arts critic Ivan Sollertinsky. Weinberg played for them a piano reduction of his Symphony No. 1; Shostakovich replied with a few appreciative comments.[58] The meeting established a friendship between the composers that endured until Shostakovich's death.[59] Weinberg thereafter was entrusted as a partner in many of the first hearings of Shostakovich's orchestral music in reductions for piano four-hands.[60] Soon after this meeting, Weinberg was accepted into the Union of Soviet Composers. The benefits he received as a member permitted him to focus on composing full-time, as well as allowed him access to food and products unobtainable to ordinary Soviet citizens.[61] Weinberg's newfound comfort, which contrasted sharply with his financial and professional standing in prewar Poland,[62] also coincided with a gradual return to normalcy in everyday Soviet life.[63]

No longer troubled by privation and with his integration into the musical culture of Moscow proceeding successfully, Weinberg composed prolifically. He added to his work catalog 21 compositions during his early years of residence in Moscow—a total of approximately 7 hours' worth of music. Many of them were quickly premiered after their completion; they were championed by Gilels, Maria Grinberg, Dmitri Tsyganov, and the Beethoven Quartet. Some of the most notable works Weinberg composed in this period include his Piano Quintet, Piano Trio, Symphony No. 2, and his String Quartets Nos. 3 – 6.[60] His music was generally received positively, but its reception was tinged with insinuations about the perceived derivativeness of his music and its dependence on wartime imagery.[64]

By the time the Soviet Union emerged among the victors in the war against Germany in 1945, Weinberg's career appeared to be heading in an auspicious direction.[62]

Postwar

The announcement proclaiming the Allied victory in Europe was broadcast across all radio stations in the Soviet Union on the night of May 9, 1945. Weinberg and his family were at the Mikhoels home when they heard the news. Natalya, the composer's wife, said that she ran downstairs to tell her father. He replied:[65]

"It is not enough to win the war. Now the world will need to be won and that is much more difficult." With those words, he cooled our elation; and we would have the chance to see how much truth there was in his words for the rest of our lives.[65]

Weinberg's professional reputation continued to gain prominence in the immediate postwar period. He was in demand as both composer and performer; and was chosen by Kara Karayev, Nikolai Peiko, and Yuri Shaporin, among others, to perform in premieres of their new works. As a composer he found support from Shostakovich and Myaskovsky. Music critics, particularly Daniel Zhitomirsky, began to write about Weinberg's music more favorably. His Piano Quintet was nominated for a Stalin Prize in 1945. The work was denied a prize because one of the jury members, the architect Arkady Mordvinov, objected to the work's use of pizzicato, a common string technique that he apparently was unfamiliar with.[66] His rebuke of the work was also interpreted as a proxy attack against Shostakovich.[67] In the event, Weinberg's friend, Georgy Sviridov,[68] ultimately won the first class prize in the chamber music category with his Piano Trio.[69]

Beyond these personal successes, major shifts in Soviet cultural policy were taking place. Increased repression and marginalization of minority groups was signaled in 1946 when Jewish candidates for the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union were pressured to withdraw. Campaigns againt formalism led by Andrei Zhdanov in literature and film began in 1946; this resulted in the censure of Anna Akhmatova, Mikhail Zoshchenko, and Sergei Eisenstein. On October 2 – 8, a smaller scale campaign took place within the Union of Soviet Composers.[70] Under the guises of encouraging composers to seek "more creative guidance" and to develop "closer ties between Soviet composers and Soviet reality",[71] the campaign was designed to subjugate Soviet music to the purposes of propaganda.[65] Lev Knipper took the stage to admonish Weinberg and Jānis Ivanovs at one of the meetings:[70]

A slackening of bonds between formal mastery and richness of ideas... This is a dangerous tendency. Our youth has to learn from the elder generation about the importance of ideology.[72]

Shaporin, Shostakovich, and Aram Khachaturian reacted by defending Weinberg. Instead, they urged, he needed the assistance of his colleagues to bring his musical style into alignment with the expectations of Soviet officialdom. Khachaturian expanded on this point by saying that critics who had praised Weinberg had done him a disservice by not balancing their views with diagnoses of his shortcomings. He also implored Weinberg to explore his "national melos", which the Armenian composer disapprovingly remarked was used "extremely rarely".[73]

In spite of this suggestion, Weinberg showed little interest in exploring folk music idioms. Excepting his Festive Pictures for orchestra, the music he composed immediately after these remarks, instead, continued to pursue and refine stylistic traits that he established during the war. Other works in which he may have heeded Khachaturian's advice are now partially or entirely lost.[74]

Persecution and arrest

On January 5, 1948, Joseph Stalin and members of the Politburo attended the Bolshoi Theatre for a performance of the opera The Great Friendship by the Georgian composer Vano Muradeli. For reasons that are unknown, the opera outraged Stalin, who immediately directed Andrei Zhdanov to organize a wider and renewed campaign against musical formalism.[75] A few days later, on January 12, Weinberg's father-in-law Mikhoels was murdered in Minsk on the orders of Stalin. The actor had been lured to his death by the critic and covert MVD informant, Vladimir Golubov; both were killed in what was officially ruled a traffic accident. Mikhoels' body was returned to Moscow and given a state funeral. Lazar Kaganovich surreptitiously conveyed to Weinberg's family his condolences, but urged them not to inquire any further about the death.[76] Weinberg was placed under constant MVD surveillance, regularly harassed by the police, and had his travel privileges curtailed.[77]

Meanwhile, the ongoing anti-formalist campaign in music necessitated a convocation of the Union of Soviet Composers. Khrennikov, who was appointed general secretary of the union, led the proceedings, but refused to engage in anti-Semitic tactics. This resulted in a number of anonymous letters accusing him of having "sold out".[78] On February 10, the Politburo published its "Resolution on the Opera 'The Great Friendship'" in Pravda. This was followed on February 14 by a ruling that listed composers and works banned from performance. Although not one of the six composers who were the campaign's most prominent targets, Weinberg's music for children was censured.[79] He was also further compromised professionally by his association with Shostakovich, who had been among the six.[80]

In spite of these developments, Weinberg appeared to have no cause for concern about his personal welfare. One of his works, the Sinfonietta No. 1, was received warmly by the press. It was also praised by Khrennikov[81] after it was performed at the December 1948 plenum of the Union of Composers:[82]

Shining evidence of the fruitfulness of the path to realism is to be found in the Sinfonietta by Weinberg, a composer who used to be under the powerful influence of modernistic art which distorted his unquestionable talent in an ugly way. Turning to the sources of Jewish folk music, Weinberg has created a brilliant work full of joie de vivre and devoted to the joyous, free working life of Jewish people in the Land of Socialism. In this work Weinberg has revealed outstanding skill and richness of imagination.[83]

The work soon established itself as a part of the Soviet orchestral repertoire and was one of Weinberg's most played works through the mid-1950s.[81] Another work, the cantata In My Native Land, which set texts that glorified Stalin, was conducted by Alexander Gauk.[84] Weinberg also composed a number of other populist works during the late 1940s, but suppressed them from being performed.[85] Other works, like the Violin Sonatina composed for Leonid Kogan, were only first played years later. Much of Weinberg's energies in these years were devoted to music for films and the circus;[86] the latter was considered by the Soviet government to be second only to the film industry in importance.[87] In 1952, Shostakovich nominated Weinberg's Rhapsody on Moldavian Themes for a Stalin Prize, but lost.[88] Weinberg was one of the few major Soviet composers of the 1940s and early 1950s who neither won a Stalin Prize nor whose nominations ever went beyond the first round of voting.[89]

Around Weinberg, official persecution of Jews intensified. In November 1948, the government dissolved the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee and arrested several of its members. Benjamin Zuskin, Mikhoels' successor at GOSET, was arrested in February 1950. He was interrogated by authorities about Weinberg, but told them he knew little except that he was a composer, one of Shostakovich's friends, and that Khrennikov considered him a "formalist".[77] Zuskin's arrest led Weinberg and his wife to believe that his would soon follow. One of her relatives, Miron Vovsi, was arrested in late January 1953 and accused of being one of the conspirators in the "doctors' plot".[84]

On February 6, Weinberg attended a performance of his Rhapsody on Moldavian Themes in an arrangement for violin and orchestra played by David Oistrakh. After the concert, Weinberg went back to his home for a late night meal accompanied by Nikolai Peiko, Boris Tchaikovsky, and his wife. At 2:00 a.m., the police arrived with an arrest warrant for Weinberg;[90] he got dressed, informed his guests that he was innocent, and was taken into police custody.[84] His working room was sealed off and apartment searched until the morning.[90][91] Fear of torture impelled him to admit his culpability to whatever charges he was accused of, irrespective of their plausibility. These included attempting to dig a tunnel to England under his home in order to flee.[90] His wife inquired regularly with officials at the Lubyanka Prison to determine the state of his arrest and to ensure that he was alive. She was soon contacted by Shostakovich, who informed her that he wrote a letter to Lavrenty Beria that vouched for Weinberg's innocence. He also arranged with her that in the event of her arrest, he would assume power of attorney over the Weinbergs' affairs and the responsibility of raising their daughter.[92] Matters changed course after Stalin's death on March 5, an event which Weinberg did not learn of until weeks later. He was released from jail on April 25.[93] To the end of his life, Weinberg rebuffed suggestions that the official persecution endured by him or other composers had been severe, and denied facts relating to these. "Evidently he had invested too much in his search for freedom to give up on it", wrote Fanning.[94]

Moscow

Thereafter Weinberg continued to live in Moscow, composing and occasionally performing as a pianist. He and Shostakovich lived near to one another, sharing ideas on a daily basis. Besides the admiration which Shostakovich frequently expressed for Weinberg's works, they were taken up by some of Russia's foremost performers and conductors, including Rudolf Barshai, Emil Gilels, Leonid Kogan, Kirill Kondrashin, Mstislav Rostropovich, Kurt Sanderling and Yevgeny Svetlanov.

Final years and posthumous reception

Towards the end of his life, Weinberg suffered from Crohn's disease and remained housebound for the last three years, although he continued to compose. He converted to Orthodox Christianity on 3 January 1996, less than two months before his death in Moscow.[95] His funeral was held in the Church of the Resurrection of the Word.[96]

A 2004 reviewer has considered him as "the third great Soviet composer, along with Prokofiev and Shostakovich".[97] Ten years after his death, a concert premiere of his opera The Passenger in Moscow sparked a posthumous revival. The British director David Pountney staged the opera at the 2010 Bregenz Festival[98] and restaged it at English National Opera in 2011.[99] Thomas Sanderling has called Weinberg "a great discovery. Tragically, a discovery, because he didn’t gain much recognition within his lifetime besides from a circle of insiders in Russia."[100]

Conversion to Orthodox Christianity

In the period immediately preceding death, Weinberg converted to the Russian Orthodox Church; sources disagree as to whether this was done under pressure or done freely. According to David Fanning, who authored a monograph about the composer, it is generally believed that this conversion occurred under pressure from his second wife, Olga Rakhalskaya, a Sunday school teacher of Jewish heritage.[101] This allegation was repeated in a 2016 interview by the composer's eldest daughter, Victoria, who doubted that the baptism was undertaken voluntarily in light of his long-standing illness,[102] Rakhalskaya denied that Weinberg had been coerced into baptism. She replied that involuntary baptism is sinful and of no value, and that Weinberg had been considering his conversion for about a year before he asked to be baptised in late November 1995.[103] The composer's youngest daughter, Anna Weinberg, has written that "father was baptized in sound mind and firm memory, without the slightest pressure from any side; this was his deliberate and conscious decision, and why he did it is not for us to judge."[96] The composer's interest in Christianity may have begun while working on the film score for Our Father in Heaven (Russian: Отче Наш, romanized: Otche Nash), directed by Boris Yermolayev in the late 1980s. A setting of the Lord's Prayer appears in the manuscript score of Weinberg's Symphony No. 21 from 1991.[104]

Works

Weinberg's output includes 22 symphonies, various works for orchestra (including four chamber symphonies and two sinfoniettas), the Violin Concerto, 17 string quartets, 8 violin sonatas (three solo and five with piano), 24 preludes for cello and six cello sonatas (two with piano and four solo), four solo viola sonatas, six piano sonatas, numerous other instrumental works, as well as more than 40 film and animation scores (including The Cranes are Flying, Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, 1958). He wrote seven operas, and considered one of them, The Passenger (Passazhirka) (written in 1967–68, premiered in 2006),[105][106] to be his most important work.[107] Beginning in 1994, new recordings and reissues of Melodiya recordings were released by Olympia, being among the first systematic efforts to bring Weinberg's music to a wider audience. Since then, numerous other labels have recorded his music, including Naxos, Chandos, ECM and Deutsche Grammophon.

According to Lyudmilla Nikitina, Weinberg emphasized the "neo-classical, rationalist clarity and proportion" of his works.[107]

Weinberg's style can be described as modern yet accessible. His harmonic language is usually based on an expanded/free tonality mixed with occasional polytonality, such as in the Twentieth Symphony, and atonality, such as in the Twelfth String Quartet or the 24 Preludes for Solo Cello. His earlier works exhibit Neoromantic tendencies and draw significantly on folk-music, whereas his later works, which came with improved social circumstances and greater compositional maturity, are more complex and austere. However, even in these later, more experimental works from the late 1960s, 70s and 80s, such as the Third Violin Sonata or the Tenth Symphony, which make liberal use of tone clusters and other devices, Weinberg retains a keen sense of tradition that variously manifests itself in the use of classical forms, more restrained tonality, or lyrical melodic lines. Many of his instrumental works contain highly virtuosic writing and make significant technical demands on performers.

Shostakovich and stylistic influences

Although he never formally studied with Shostakovich, the older composer was an important influence on Weinberg. This is particularly noticeable in his Twelfth Symphony (1975–1976, Op. 114), which is dedicated to the memory of Shostakovich and quotes from a number of the latter's works. Other explicit connections include the pianissimo passage with celesta which ends the Fifth Symphony (1962, Op. 76), reminiscent of Shostakovich's Fourth; the quote from one of Shostakovich's 24 Preludes and Fugues in Weinberg's Sixth Piano Sonata (1960, Op. 73); and numerous quotes from Shostakovich's First Cello Concerto and Cello Sonata in Weinberg's 21st Prelude for Solo Cello. These explicit connections should not be interpreted, however, to mean that musical influences went in only one direction, from Shostakovich to Weinberg. Shostakovich drew significant inspiration from Weinberg's Seventh Symphony for his Tenth String Quartet;[108] Shostakovich also drew on some of the ideas in Weinberg's Ninth String Quartet for the slow movement of his Tenth Quartet (opening bars of Weinberg's Ninth), for his Eleventh Quartet (first movement of Weinberg's Ninth) and for his Twelfth Quartet (F-sharp major ending);[109] and in his First Cello Concerto of 1959, Shostakovich re-used Weinberg's idea of a solo cello motif in the first movement that recurs at the end of the work to impart unity, from Weinberg's Cello Concerto (1948, Op. 43).[110]

It is also important to note that Weinberg does not restrict himself to quoting Shostakovich. For example, Weinberg's Trumpet Concerto quotes Felix Mendelssohn's well-known Wedding March; his Second Piano Sonata (written in 1942, before moving to Moscow) quotes Haydn; and his Twenty First Symphony quotes a Chopin ballade. Such quotations are stylistic features shared by both Weinberg and Shostakovich.[111]

More general similarities in musical language between Shostakovich and Weinberg include the use of extended melodies, repetitive themes, and methods of developing the musical material.[112] However, Nikitina states that "already in the 60s it was obvious that Weinberg's style was individual and essentially different from the style of Shostakovich.".[112]

Along with Shostakovich, Nikitina identifies Prokofiev, Nikolai Myaskovsky, Béla Bartók and Gustav Mahler as formative influences.[107] Ethnic influences include not only Jewish, but also Belarusian, Moldavian, and Polish music.[113] Weinberg has been identified by a number of critics as the source of Shostakovich's own increased interest in Jewish themes.[108][114]

Operas

- The Passenger, Op. 97 (1967/68) after the book by Zofia Posmysz[115]

- The Madonna and the Soldier «Мадонна и солдат», Op. 105 to a libretto by Alexander Medvedev (1970) [116]

- The Love of d'Artagnan «Любовь Д’Артаньяна», after The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas (1971)

- Pozdravlyayem! «Поздравляем!», Op. 111 after Mazel Tov by Sholem Aleichem (1975) [117]

- Lady Magnesia «Леди Магнезия», Op. 112 after Passion, Poison and Petrifaction by George Bernard Shaw (1975) [118]

- The Portrait, Op. 128 after Nikolai Gogol (1980)

- The Idiot, Op. 144 after Dostoyevsky (1985)

Selected recordings

- Chamber Symphonies 1–4. East-West Chamber Orchestra/Rostislav Krimer. Naxos 8.574063 (2019) and 8.574210 (2021).[119][120]

- Violin Concerto: several recordings, with soloists Leonid Kogan (1961),[121] Linus Roth (2014)[122] and Gidon Kremer (2021)[123]

- Sonata For Clarinet & Piano (1945): Joaquin Valdepenas (clarinet), Dianne Werner (piano); Jewish Songs after Shmuel Halkin (1897–1960) for voice & piano, Op. 17 (1944): Richard Margison (tenor), Dianne Werner (piano); Piano Quintet (1944), Op. 18: ARC Ensemble, 2006.[124]

- Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op.10, 1942; Symphony for string orchestra & harpsichord No. 7 in C major, Op. 81, 1964: Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra, Thord Svedlund (cond.), Chandos, 2010.[125]

- Symphony No. 17, Op. 137 "Memory"; Symphonic Poem, Op. 143 "The Banners of Peace": USSR Radio Symphony Orchestra, Vladimir Fedoseyev (cond.), Olympia OCD 590, 1996.[126]

Complete editions

- Complete Works for Solo Cello (24 Preludes and Four Sonatas): Yosif Feigelson, Naxos, 1996.[127]

- Complete String Quartets Vol. 1 – 6: Quatuor Danel, CPO, 2008–2012.[128]

- Complete Songs Vol. 1: Olga Kalugina (soprano) and Svetlana Nikolayeva (mezzo-soprano), Dmitri Korostelyov (piano), Toccata Classics (with Russian sung texts and translations), 2008.[129]

Video

- Opera The Passenger, Op. 97 (1967/68) sung in German, Polish, Russian, French, English, Czech, and Yiddish: Michelle Breedt, Elena Kelessidi, Roberto Sacca, Prague Philharmonic Choir, Vienna Symphony Orchestra Teodor Currentzis (cond.), David Pountney (dir.) at the Bregenzer Festspiele, 2010 (Non-DVD compatible Blu-ray).[130]

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 According to Weinberg's own reckoning, he was born on December 8, 1919. His birth certificate withal states the date as January 12, 1919. The Polish musicologist and Weinberg biographer, Danuta Gwizdalanka, believes his birth occurred on December 8, 1918.[12]

- ↑ Weinberg stated that his mother's maiden surname was Kotlicka. However, documents preserved at the Chopin University of Music, as well as notations in surviving family photographs record her name as Sura Dwojra Sztern.[17]

Citations

- ↑ Steve Schwarz, review of The Golden Key on Classical Net Review, 2004.

- ↑ da Fonseca-Wollheim, Corinna (November 1, 2017). "Review: Violinist Gidon Kremer Shares 24 Soviet Snapshots". The New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka, Danuta (February 12, 2015). "Unknown Facts From Mieczysław Wajnberg's Biography". Culture.pl. Warsaw: Adam Mickiewicz Institute. Archived from the original on January 5, 2024. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- 1 2 Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 25.

- ↑ שװאַרץ, פֿיליפּ (October 27, 2023). "Immortalizing the work of composer Mieczysław (Moyshe) Weinberg". The Forward. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 Fanning 2019, p. 23.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, pp. 144–145.

- 1 2 Fanning 2019, p. 8.

- ↑ Skans, Per. "What is in a name?: Per Skans on Mieczysław Weinberg's surname". music-weinberg.net. Archived from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

Why Weinberg? Why not Vainberg? Why not Wainberg? Or Vajnberg? Or Wajnberg? Weinberg is correct, all other spellings are wrong! [...] I confess having a certain guilt myself, since I once accepted—without checking them—certain rumors that Weinberg himself preferred the spelling 'Vainberg'.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, p. 16.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Tsodikova 2009a.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 18.

- 1 2 Ovchinnikov 2003.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, p. 15.

- 1 2 Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 15.

- ↑ "Иллюстрации к "Дерево Жизни"". zhurnal.lib.ru.

- ↑ Tsodikova, Ada (February 20, 2009). "Дерево Жизни". ArtLib.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on February 27, 2009. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, pp. 13–14.

- 1 2 3 Fanning 2019, p. 17.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 22.

- ↑ Medvedev 2004.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, p. 19.

- ↑ Elphick 2020, p. 35.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 29.

- ↑ Elphick 2020, p. 37.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 27.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, p. 18.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 30.

- 1 2 Fanning 2019, p. 21.

- 1 2 Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 Fanning 2019, p. 22.

- 1 2 Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 35.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 37.

- ↑ Elphick 2020, p. 41.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 36.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, pp. 37–38.

- 1 2 3 Fanning 2019, p. 26.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 38.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, p. 27.

- ↑ Elphick 2020, p. 49.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 39.

- ↑ Elphick 2020, p. 57.

- 1 2 Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 40.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, p. 32.

- 1 2 3 Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 41.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, p. 33.

- ↑ Elphick 2020, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 42.

- ↑ Elphick 2020, p. 59.

- ↑ Elphick 2020, pp. 59–60.

- 1 2 Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 43.

- ↑ Elphick 2020, p. 69.

- 1 2 Elphick 2020, p. 70.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, p. 41.

- ↑ Weinberg 1976, p. 48.

- 1 2 Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 47.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, pp. 44–45.

- 1 2 Elphick 2020, p. 87.

- ↑ Elphick 2020, p. 80.

- ↑ Elphick 2020, pp. 80–81.

- 1 2 3 Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 51.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 49.

- ↑ Frolova-Walker 2016, p. 98.

- ↑ Sviridov & Weinberg 2023, p. 39.

- ↑ Frolova-Walker 2016, p. 291.

- 1 2 Fanning 2019, p. 49.

- ↑ Elphick 2020, p. 98.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, p. 50.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Frolova-Walker 2016, pp. 222–223.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, pp. 60–61.

- 1 2 Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 65.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 67.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, p. 64.

- ↑ Elphick 2020, p. 108.

- 1 2 Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 64.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 68.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, p. 68.

- 1 2 3 Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 77.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 69.

- ↑ Elphick 2020, p. 123.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 72.

- ↑ Frolova-Walker 2016, p. 123.

- ↑ Frolova-Walker 2016, p. 124.

- 1 2 3 Elphick 2020, p. 124.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 78.

- ↑ Gwizdalanka 2022, p. 79.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, p. 88.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, p. 70.

- ↑ Reilly, Robert R. (February 2000), "Light in the Dark: The Music of Mieczyslaw Vainberg", Crisis Magazine, reproduced at http://www.music-weinberg.net/biography.html.

- 1 2 Gorfinkel, Ada (March 7, 2012). "Моисей (Мечислав) Вайнберг ["Moisey (Mieczyslaw) Weinberg"]" (in Russian). Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ↑ Steve Schwarz, review of The Golden Key on Classical Net Review, 2004.

- ↑ David Poutney (September 8, 2011). "The Passenger's journey from Auschwitz to the opera". The Guardian. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

- ↑ Andrew Clements (September 20, 2011). "The Passenger – review". The Guardian. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

- ↑ Rebecca Schmid (December 21, 2016). "Recognition for a Composer Who Captured a Century's Horrors". New York Times. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, p. 162.

- ↑ Blumina, Elizaveta (February 26, 2016). ""Я никогда не говорила об этом, но сейчас, думаю, пришло время" ["I never talked about it, but now, I think, the time has come"]". Академическая музыка (in Russian). Colta.ru. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- ↑ Rakhalskaya 2016.

- ↑ Fanning, David (2014), Notes to Symphony 21, Toccata Classics CD TOCC 0193.

- ↑ World premiere (in concert version): December 25, 2006, Moscow International House of Music "Состоялась мировая премьера оперы "Пассажирка" | Радио России". Retrieved December 29, 2006.

- ↑ Staged premiere: July 21, 2010, Bregenz Festival "Passagierin10 | Bregenz Festival". Archived from the original on November 12, 2009. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Nikitina 2001.

- 1 2 Sobolev, Oleg (May 15, 2014). "Мечислав Вайнберг: Глоссарий ["Mieczyslaw Weinberg: Glossary"]". ART-1 (in Russian). Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ↑ Fanning, David (2010), Notes to String Quartets Vol. 4, CPO CD 777 394–2, p. 15.

- ↑ Fanning, David (2012), Notes to Cello Concerto and Symphony 20, Chandos CD CHSA 5107, pp. 5 – 6.

- ↑ Ross, Alex (May 8, 2019). "The Wrenching, Rediscovered Compositions of Mieczyslaw Weinberg". The New Yorker. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- 1 2 Nikitina, Lyudmilla (1994), "Почти любой миг жизни — работа…" ["Almost every moment of my life is work"], Музыкальная академия [Journal of the Academy of Music] No. 5, pp. 17–24.

- ↑ Fanning 2019, p. 77.

- ↑ "Mieczysław Weinberg". holocaustmusic.ort.org. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- ↑ Bregenzer Festspiele Archived May 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine 2010.

- ↑ "Madonna und der Soldat". www.peermusic-classical.de.

- ↑ "Werkliste: Weinberg, Mieczyslaw | Internationale Musikverlage Hans Sikorski". www.sikorski.de.

- ↑ "Weinberg, Mieczyslaw: LADY MAGNESIA. Oper in einem Akt | Internationale Musikverlage Hans Sikorski". www.sikorski.de.

- ↑ Vaĭnberg, M.; Krimer, Rostislav; East-West Chamber Orchestra (2019), Chamber symphonies nos. 1 and 3 (in no linguistic content), Naxos, OCLC 1141865649

- ↑ Vaĭnberg, M.; Fedorov, Igor; Krimer, Rostislav; East-West Chamber Orchestra; Yuri Bashmet International Music Festival (2021), Chamber symphonies nos. 2 and 4 (in no linguistic content), Naxos Regular CD (NRE), OCLC 1295012144

- ↑ Vaĭnberg, M.; Kogan, Leonid; Kondrashin, Kirill; Svetlanov, Yevgeny; Moskovskai︠a︡ gosudarstvennai︠a︡ filarmonii︠a︡. Simfonicheskiĭ orkestr; Gosudarstvennyĭ simfonicheskiĭ orkestr SSSR (1997), Symphony no. 4 in A minor, op. 61 ; Violin concerto in G minor, op. 67 ; Rhapsody on Moldavian themes : op. 47, no. 1 (in no linguistic content), London: Olympia, OCLC 39386107

- ↑ Roth, Linus; Kütson, Mihkel; Britten, Benjamin; Vaĭnberg, M.; Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin (2013), Violin concertos (in no linguistic content), [Amersfoort, Netherlands]: Challenge Classics, OCLC 1051211770

- ↑ Vaĭnberg, M.; Kremer, Gidon; Pētersone, Madara; Gatti, Daniele; Gewandhausorchester Leipzig (2021), Violin concerto ; Sonata for two violins (in no linguistic content), Accentus Music, OCLC 1260451685

- ↑ Valdepeñas, Joaquin; Nel, Anton; Buccheri, Elizabeth; Long, Timothy; Carlyss, Earl; Adkins, Darrett; Schein, Ann; Vaĭnberg, M.; Hough, Stephen; Ravel, Maurice; Aspen Music Festival (2014), Chamber music (in no linguistic content), OCLC 899017872

- ↑ Vaĭnberg, M.; Svedlund, Thord; Göteborgs symfoniker (2010), Symphony no. 1 ; Symphony no. 7 (in no linguistic content), Colchester, Essex, England: Chandos, OCLC 811454342

- ↑ Weinberg, Mieczysław; Fedoseev, Vladimir Ivanovič; Skans, Per; Orkiestra Symfoniczna Radia Wszechzwiązkowego (Moskwa) (1996), Symphony no. 17, op. 137 "Memory" ; The banners of peace" op. 143 (in no linguistic content), London: Olympia Compact Discs, OCLC 947750726

- ↑ Feigelson, Josef; Vaĭnberg, M. (2010), WEINBERG, M. : Cello Music (Complete), Vol. 2 - Cello Solo Sonatas Nos. 2-4 (Feigelson), Hong Kong: Naxos Digital Services Ltd., OCLC 767879391

- ↑ Vaĭnberg, M.; Quatuor Danel (2014), Complete string quartets (in no linguistic content), Georgsmarienhütte: CPO, OCLC 906158761

- ↑ Vaĭnberg, M.; Peretz, Isaac Leib; Blok, Aleksandr Aleksandrovich; Mistral, Gabriela; Kalugina, Olʹga; Nikolaeva, Svetlana; Korostelev, Dmitriĭ (2008), Complete songs. Volume one (in Russian), London: Toccata Classics, OCLC 811337586

- ↑ Weinberg, Mieczysław; Medvedev, Alexander; Posmysz, Zofia; Currentzis, Teodor; Pountney, David; Breedt, Michelle; Saccà, Roberto; Kelessidi, Elena; Ruciński, Artur; Doneva, Svetlana; Sokolova, Liuba; Voje, Angelica; Wiener Symphoniker; Pražský Filharmonický Sbor; Bregenzer Festspiele (2015), The passenger = Die Passagierin (in German), [Halle (Saale)]: Arthaus Musik, OCLC 1159977309

Sources

- Elphick, Daniel (2020). Music Behind the Iron Curtain: Weinberg and his Polish Contemporaries. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-49367-3.

- Fedoseyev, Vladimir; Yusova, Olga (May 5, 2016). "Владимир Федосеев: «В искусстве периодически наступают антракты»" [Vladimir Fedoseyev: "There are occasional intermissions in art"]. BelCanto.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- Fanning, David (2019). Mieczysław Weinberg: In Search of Freedom (2nd ed.). Hofheim, Germany: Wolke Verlag. ISBN 978-3-95593-050-9.

- Frolova-Walker, Marina (2016). Stalin's Music Prize: Soviet Culture and Politics. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300208849.

- Genina, Liana (August 1962). "Портреты: "Все будет хорошо" (О творчестве М. Вайнберга)" [Portraits: "Everything Will be Fine" (On the Works of M. Weinberg)]. Sovyetskaya Muzyka [Soviet Music] (in Russian). 285 (8). Archived from the original on January 12, 2024. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- Gwizdalanka, Danuta (2022). Мечислав Вайнберг—композитор трех миров [Mieczysław Weinberg: A Composer From Three Worlds] (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: Композитор [Composer]. ISBN 978-5-7379-1013-6.

- Medvedev, Alexander (2004). "Вайнберг Мечислав Самуилович" [Weinberg Mieczysław Samuilovich]. Great Russian Encyclopedia (in Russian). Archived from the original on December 28, 2023. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- Nikitina, Lyudmila (1972). Симфонии М. Вайнберга [The Symphonies of M. Weinberg] (in Russian). Moscow: Muzyka.

- Nikitina, Lyudmila (October 1980). "На автором концерте... М. Вайнберга" [At the Composer's Concert of... M. Weinberg]. Sovyetskaya Muzyka [Soviet Music] (in Russian). 503 (10). Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- Nikitina, Lyudmila (Autumn–Winter 1994). "Почти любой миг жизни — работа...: Страницы биографии и творчества Мечислава Вайнберга" [Almost Every Living Moment... Work: Pages from the Biography and Works of M. Weinberg]. Muzykalnaya Akademiya [Musical Academy] (in Russian). 650 (5). Archived from the original on January 12, 2024. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- Nikitina, Lyudmila (January 20, 2001). "Weinberg [Vaynberg], Moisey [Mieczysław] Samuilovich". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- Ovchinnikov, Ilya (February 26, 2003). "Возвращение Вайнберга" [Weinberg's Return]. Russian Journal (in Russian). Archived from the original on December 28, 2023. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- Sviridov, Georgy; Weinberg, Mieczysław (2023). Belonenko, Alexander (ed.). Мечислав Вайнберг и Георгий Свиридов: переплетение судеб [Mieczysław Weinberg and Georgy Sviridov: Interwoven Fates] (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: Композитор [Composer]. ISBN 978-5-7379-1029-7.

- Rakhalskaya, Olga (March 26, 2016). "Отзыв-опровержение Ольги Рахальской на интервью Виктории Вайнберг Елизавете Блюминой" [Olga Rakhalskaya's Reply and Rebuttal to Victoria Weinberg's Interview with Elizaveta Blumina]. Музыкальное обозрение [Musical Review] (in Russian). Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- Tsodikova, Ida (February 6, 2009a). "Моисей (Мечислав) Вайнберг" [Moisei (Mieczysław) Weinberg]. ArtLib.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on December 28, 2023. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- Weinberg, Mieczysław (October 1960). "На пороге нового мир" [At the Cusp of a New World]. Sovyetskaya Muzyka [Soviet Music] (in Russian). 275 (10). Archived from the original on January 12, 2024. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- Weinberg, Mieczysław (1976). "Величие музыки Дмитрия Шостаковича" [The Greatness of Dmitri Shostakovich's Music]. In Schneerson, Grigory (ed.). Д. Шостакович: статьи и материалы [D. Shostakovich: Articles and Materials] (in Russian). Moscow: Советский композитор [Soviet Composer].

- Weinberg, Mieczysław; Zhmodyak, Inna (September 1988). "Честность, правдивость, полная отдача" [Integrity, Truthfulness, Total Devotion]. Sovyetskaya Muzyka [Soviet Music] (in Russian). 598 (9). Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

Further reading

In German

- Sapper, Manfred (2010). Die Macht der Musik (in German). Berlin: BWV, Berliner Wiss.-Verl. ISBN 978-3-8305-1710-8.

- Mogl, Verena (November 26, 2019). "Juden, die ins Lied sich retten" - der Komponist Mieczyslaw Weinberg (1919-1996) in der Sowjetunion (in German). Münster New York: Waxmann. ISBN 978-3-8309-3137-9.

- Gwizdalanka, Danuta (April 14, 2020). Der Passagier (in German). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-11409-7.

In Polish

- Gwizdalanka, Danuta; (Poznań)., Teatr Wielki im. Stanisława Moniuszki (2013). Mieczysław Wajnberg (in Polish). Poznań: Teatr Wielki im. Stanisława Moniuszki. ISBN 978-83-913521-6-8.

In Russian

- Khazdan, Evgenia Петербургская опера: «Идиот» в Мариинском театре (Petersburg Opera: "The Idiot" at the Mariinsky Theatre). Музыкальная академия. 2016, No. 4. С. 20–23. (in Russian, registration required)

- Мечислав Вайнберг (1919—1996). Страницы биографии. Письма (Материалы международного форума). Москва, 2017.

- Мечислав Вайнберг (1919—1996). Возвращение. Международный форум. Москва, Большой театр России, 2017.

External links

- Mieczysław Weinberg at IMDb

- Mieczyslaw Weinberg: The Composer and His Music

- The International Mieczysław Weinberg Society

- Daniel Elphick's blog on Weinberg

- Biographical entry on the OREL Foundation's website

- Discography of Mieczysław Weinberg's music

- Dissertation in Russian by Yevgenia Khazdan on Weinberg's Jewish Songs