Mikhail Borodin | |

|---|---|

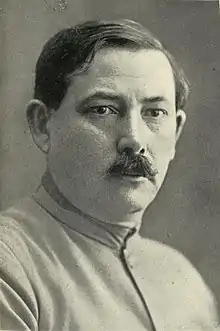

1920s portrait of Borodin | |

| Born | Mikhail Markovich Gruzenberg 9 July 1884 |

| Died | 29 May 1951 (aged 66) |

| Other names | Michael Gruzenberg Michael Borodin |

| Occupation(s) | Comintern agent, military and political advisor |

| Organization | Communist International |

| Political party | General Jewish Labour Bund (1900–1903) Bolsheviks (from 1903) |

| Spouse | Fanya Orluk |

| Children | Fred Borodin Norman Borodin |

Mikhail Markovich Gruzenberg,[lower-alpha 1] known by the alias Borodin[lower-alpha 2] (9 July 1884 – 29 May 1951), was a Bolshevik revolutionary and Communist International (Comintern) agent. He was an advisor to Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang (KMT) in China during the 1920s.

Born in a rural part of the Russian Empire (now Belarus), to a Jewish family, Borodin joined the General Jewish Labour Bund at age sixteen, and then the Bolsheviks in 1903. After being arrested for participating in revolutionary activities, Borodin fled to America, attended Valparaiso University, started a family, and later established an English school for Russian Jewish immigrants in Chicago. Upon the success of the October Revolution in 1917, Borodin returned to Russia, and served in various capacities in the new Soviet government. From 1919, he served as an agent of the Comintern, travelling to various countries to spread the Bolshevik revolutionary cause. In 1923, Vladimir Lenin picked Borodin to lead a Comintern mission to China, where he was tasked with aiding Sun Yat-sen and his Kuomintang. Following Sun's death, Borodin assisted in the planning of the Northern Expedition, and later became an integral backer of the KMT leftist government in Wuhan.

Following a purge of communists from the Kuomintang, Borodin was forced to return to the Soviet Union in 1927, where he would remain for the rest of his life. He once again served in various positions within the Soviet government, and later helped found the English-language Moscow News newspaper, of which he would become the editor-in-chief. During the Second World War, he additionally served as editor-in-chief of the Soviet Information Bureau. Amidst rising antisemitism in the Soviet Union during the late 1940s, Borodin was arrested and deported to a prison camp. He died in 1951 and was officially rehabilitated in 1964.

Early life

Borodin was born Mikhail Markovich Gruzenberg (Russian: Михаи́л Ма́ркович Грузенберг) to a Jewish family in Yanovichi, Russian Empire, now part of Vitebsk Region, Belarus, on 9 July 1884. At a very young age, he began work as a boatman on the Western Dvina, traversing the stretch of the river between Vitebsk, Dvinsk, and Riga, now the capital of Latvia. He later moved to Riga, where he attended Russian-language night schools while working in the city's port.[1] He joined the General Jewish Labour Bund at age sixteen, switching allegiance to Vladimir Lenin's Bolsheviks in 1903.[2] He became a close associate of Lenin, making use of his knowledge of the Yiddish, German, and Latvian languages in work as a Bolshevik agent in the empire's northwest region. In mid-1904, he was ordered to travel to Switzerland to meet Lenin, who had gone into exile. Following the "Bloody Sunday" massacre of unarmed protesters by Tsarist troops in Saint Petersburg on 9 January 1905, Borodin returned to Russia, organised revolutionary activity in Riga, and was later selected to attend the Bolshevik conference at Tampere, where he met Joseph Stalin.[3]

In 1906, he attended the 4th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in Stockholm.[4] Later that year, he was picked up by the Tsarist police in Saint Petersburg, and given the choice of either being sent to Siberia or exile in Europe. Borodin chose exile, and by October, he had arrived in London, where police took notice of his activities and promptly ordered him out of the country. In 1907, he arrived in America, first to Boston, and then on to Chicago.[5] While there, he attended classes at Valparaiso University in Indiana, taught English to immigrant children at Jane Addams' Hull House, and then opened his own school for Russian Jewish immigrants, which later grew into a successful business venture.[6] During his time in the United States, Borodin associated nominally with the Socialist Party of America, whilst simultaneously promoting the Russian revolutionary cause in the immigrant community.[7]

Following the October Revolution of 1917, he returned to Russia in July 1918, and began working in the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs of the Russian Soviet Republic.[8][9] Some months later, he returned to America to relay Lenin's "Letter to American Workers", a propaganda message intended to counteract negative views of the Russian communists following the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.[8][10] He also proposed a joint propaganda campaign with George Creel's Committee on Public Information, though this never came to fruition. Having become disillusioned by the intensity of American criticism of the new Soviet government, Borodin gave up hope of co-operation with the Americans, and returned to Russia.[10] He then moved on to Stockholm, where he met American writer Carl Sandburg, with whom he discussed the Bolshevik revolution.[11]

In March 1919, Borodin participated in the first congress of the Communist International (Comintern) in Moscow.[12] After the congress, he embarked on his first Comintern assignment, travelling with a falsified Mexican diplomatic passport. Borodin travelled through a variety of European countries, deposited Soviet funds in a Swiss bank account, and otherwise tried to raise money to finance the establishment of communist parties in the Americas. He then travelled to Santo Domingo, from which he booked passage to New York, where he arrived in August 1919.[13] His mission was known to the American authorities, and as such he was briefly detained by the Bureau of Investigation upon arrival. After his release, he went on to his former home, Chicago, where the Socialist Party of America was embroiled in a dispute between its left wing, who wanted to establish a communist party and join the Comintern, and the "regulars", who were opposed. Borodin, conscious of the fact that his activities were being monitored, kept a low profile while in America, and on 4 October 1919, he slipped across the border into Mexico.[14]

In Mexico, he met Indian revolutionary M. N. Roy, the American writers Carleton Beals and Michael Gold, and American communist Charles Phillips. Borodin taught Roy about the Russian Revolution and communism, and it was under Borodin's influence that he took up communist beliefs.[15] Together with the newly emboldened Roy, he helped establish the Mexican Communist Party. During his time in Mexico, Borodin sent reports of Roy's exploits to Lenin, who subsequently invited him to attend the 2nd World Congress of the Comintern in Moscow, which would take place in July–August 1920.[16] Leaving Mexico in December 1919, Borodin, Roy, and Phillips travelled to western Europe, where they intended to spread the communist cause in the lead up to the congress, specifically hoping to establish a communist party in Spain.[15] Arriving in Moscow in the weeks before the congress, Borodin introduced Roy to Lenin, after which he went on to become a major figure in the Comintern.[16]

Borodin later returned to Britain under the alias "George Brown", where he was tasked with ascertaining the cause of the revolution's failure there, and reorganising the British Communist Party.[17] After several months of covert activities, he was jailed for six months on 29 August 1922 in Glasgow, ostensibly for breaking immigration regulations, though his political mission was known.[18] He was then deported to Russia. Upon his arrival in Moscow, Lenin informed him that he had been chosen as the leader of a Comintern mission to China. He reached Beijing in the latter part of 1923, and arrived in Guangzhou, the seat of Sun Yat-sen's revolutionary government, on 6 October.[19][20]

China

Advisor to Sun Yat-sen (1924–1925)

Following Sun Yat-sen's request for help from the Comintern, Borodin was ordered to lead a contingent of Soviet advisors to Guangzhou, where Sun had established a revolutionary government in the aftermath of the Constitutional Protection Movement.[21] Borodin understood no Chinese; English was to be the medium of discussion between the two. At this time, he was accompanied by Ho Chi Minh, the future Vietnamese communist leader, who then served as his secretary.[22] Borodin was known for speaking with a clear midwestern American accent that offered no indication of his Russian origin, allowing him to easily communicate with the largely anglophone and American-educated leadership of the Kuomintang (KMT).[23][24]

Greeted upon his arrival in Guangzhou by Eugene Chen, with whom he later became close, Borodin found that Sun's government was teetering on the brink of collapse. Faced with rampant corruption, anti-Bolshevik feeling in parts of the KMT, and the ever-present threat of the warlords and the Beijing-based Beiyang government, Borodin was tasked with reforming the Kuomintang into a potent revolutionary force.[25]

He negotiated the First United Front between Sun's KMT and the nascent Chinese Communist Party (CCP), convincing that party, which consisted of only about 300 members at that time,[26] that the alliance was in its long-term interest, as it would facilitate the organisation of both urban and rural workers. Under Borodin's tutelage, both parties were reorganised on the Leninist principle of democratic centralism, and training institutes for mass organisation were established, such as the Peasant Training Institute, where the young Mao Zedong served, and the Whampoa Military Academy, which trained officers for the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek. He arranged shipments of Soviet arms and shrewdly kept a balance between the middle-class elements of the KMT and the more radical CCP.[27][28]

When the forces of rebel general Chen Jiongming threatened Sun's base in Guangzhou in November 1923, Borodin proposed a mobilisation of the masses in defence of the city.[29] To accomplish this, he suggested a promise of redistribution of landlord property to the local peasantry, an eight-hour working day for urban labourers, and a minimum wage. Sun rejected land reform because of strong opposition from some of his allies, though agreed to the proposals in principle, and offered a 25% rent reduction instead.[29][30] In the event, Sun's military forces were able to drive the rebels away, and the rent reduction proposal was never implemented.[29]

In 1924, KMT leaders gradually grew weary of the influence of the Communist Party. When Borodin was confronted on this subject, he stated that continued Soviet aid was linked to co-operation with the communists. Leading figures in the CCP, including Mao Zedong, however, came to advocate an end to co-operation. Borodin made clear to them that their continued participation in the United Front was both necessary and expected.[31] When a group of American supporters of the KMT attempted to warn Sun of the danger of the growing Soviet influence in his party, asking, in a subtle anti-semitic attack, whether Sun knew Borodin's real name, Sun replied that it was "Lafayette".[32][33] In the latter part of 1924, Borodin travelled to meet the "Christian General" Feng Yuxiang, whom he attempted to bring into the Kuomintang fold. Feng and Borodin got along well, and although Feng did not join the KMT at this juncture, he did allow KMT propagandists and agitators to embed with his army, bolstering its cause.[34]

After Sun's death: the Northern Expedition (1925–1927)

After Sun's death in 1925, the growth of a radical peasant and worker movement continued to be encouraged by the CCP, but was opposed by many in the KMT.[35] The leftist wing of the KMT was strengthened by the Canton–Hong Kong strike, which broke out amidst anti-imperialist fervour after the British-run police force of the Shanghai International Settlement opened fire on Chinese protestors on 30 May 1925.[36] Borodin wrote that: "[the Canton–Hong Kong strike] was really not an economic strike. It was the quintessence of the anti-imperialist movement and the most militant expression of that movement. That it concentrated on Great Britain was not a matter of specific policy. Had it been Formosa or the Philippines it would have been directed against Japan or America. It was a political strike pure and simple".[36] Against this backdrop of rising leftist influence, in November 1925, a faction of anti-communist KMT members called the "Western Hills Group" met near Beijing, where they issued a declaration terminating Borodin's relationship with the KMT, and expelling all communists from the party. This pronouncement had no effect, and Chiang Kai-shek wrote an open letter defending Borodin, the communists, and the KMT's relationship with the Soviet Union.[37]

The following year, however, Borodin gradually came into conflict with Chiang, who was vying for the position of Sun's successor. Borodin initially opposed Chiang's planned Northern Expedition to reunify China, and grew concerned about Chiang's growing standing in the NRA.[38] When Borodin went north in another attempt to bring Feng Yuxiang and his Guominjun into the Kuomintang in early 1926, Chiang began preparations to consolidate his position in Guangzhou.[39] Borodin's fears were then realised in March 1926, when Chiang launched the "Canton Coup" purge of hardline leftists who opposed the launch of the expedition.[38]

Following the purge, Borodin returned from the north on Chiang's request, began negotiations, and reached a narrow compromise to hold the First United Front together. On Joseph Stalin's suggestion, Borodin agreed to continue Soviet aid to the KMT, and to support the Northern Expedition, which began in July 1926.[40] At a Comintern conference in November 1926, Stalin explained his continued support for the KMT, saying that "The exit of Chinese communists from the Kuomintang would be the gravest error", going on to argue that the CCP needed to work through the new government, forming a bridge between the state and the peasantry. Borodin agreed, noting that the purpose of the Northern Expedition was "not the establishment of a proletarian state, but the creation of conditions which would give an impetus to the mass movement". In Borodin's view, the goal of the China mission was to facilitate a bourgeois-democratic revolution led by an alliance of workers, peasants, petite bourgeoisie and bourgeoisie, so as to create the conditions necessary for a future proletarian revolution.[41] With tensions between the left and right threatening to break into armed conflict in Guangzhou, Borodin became convinced that it was necessary to expand the base of the anti-imperialist movement, providing adequate space for both factions. For this reason, he had agreed to support the Northern Expedition.[42]

Borodin and a group of Soviet military advisers led by Vasily Blyukher (known by the alias "Galen") were responsible for planning the expedition.[43] Whilst Chiang Kai-shek had been named commander-in-chief of the National Revolutionary Army, he was not personally involved in the planning phase of the operation. Having studied the history of the mid-19th century Taiping Rebellion, Borodin decided that the expedition should head inland toward Hankou, an industrial and commercial centre with a large worker class, so as to avoid conflict with British and Japanese interests in the Shanghai area.[41] As the expedition progressed, Borodin moved together with the KMT government from Guangzhou to Hankou, which was merged with two other cities to form Wuhan. Chiang, who refused to move his headquarters from Nanchang to Wuhan, gradually came into conflict with the leftist-dominated KMT government from December 1926,[44] and Borodin publicly disavowed him the following month.[45]

During his time in Wuhan, Borodin advocated a strategy of directing anti-imperialist feeling against Britain specifically, rather than other colonial powers such as America and France.[46] A series of anti-British demonstrations carried out under Borodin's advice in December 1926–January 1927 led to the occupation of the concessions at Hankou and Jiujiang by NRA troops, forcing the British to agree to their return to Chinese jurisdiction in an agreement negotiated by Eugene Chen.[46]

In a startling turn of events, Borodin's wife Fanya was captured by White Russian mercenaries employed by warlord Zhang Zongchang whilst travelling on board the ship Pamyat Lenina between Shanghai and Wuhan on 28 February 1927, after which she was held hostage in Jinan, Shandong.[47][48] Borodin's anxieties heightened even further in April 1927, when Chiang initiated a new purge of KMT leftists and communists, known as the "Shanghai Massacre". Borodin and the communists gave their backing to the left-wing KMT government in Wuhan led by Wang Jingwei and Eugene Chen against Chiang's rival Nanjing government. KMT attacks on communists and peasant leaders would continue, however, and even Wuhan army leader Tang Shengzhi's forces harassed local communist groups, preventing their access to Wuhan's armouries.[49][50]

Revelations in the Arcos Affair

Borodin's activities were brought into the British political limelight during the Arcos Affair of May 1927. Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin stated in parliament that his government had decrypted a telegram dated 12 November 1926 from the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs to the Soviet envoy in Beijing. The telegram read:[51]

"I herewith communicate department's decision for your execution.

- Until a Soviet representative is appointed to Peking [Beijing], Comrade Borodin is to take his orders direct from Moscow.

- The Far Eastern Bureau to be informed that all its decisions and measures regarding questions of the general policy of the Kuomintang in China and of military political work must be agreed on with Comrade Borodin. In the event of differences of opinion arising on these questions they must be referred to Moscow for investigation. Borodin and the Far Eastern Bureau must keep Moscow's representatives in Peking informed of all their decisions and moves with regard to these questions.

- Comrade Borodin's appointment as official Soviet representative in Canton [Guangzhou] is considered inadvisable. Borodin is to remain (in charge) of the work in the provinces under Canton rule, and an official representative to the Canton Government is to be appointed".

According to Baldwin, this contradicted February 1927 statements by Soviet representatives in London to the effect that Borodin "was a private citizen in service of the Chinese government", and "that the Soviet government were not answerable for his actions".[52] Baldwin declared that: "The denials of any responsibility for Borodin's actions...were therefore untrue and were made only in the hope of deceiving His Majesty's Government and the British public while under their cloak Borodin was, in fact, carrying on his anti-foreign and anti-British activities as the authorised agent of the Soviet Government and by their orders".[53] Borodin's orchestration of anti-British demonstrations and his role in the occupation of the British concessions had brought him notoriety in London; his connection to Soviet government was made public in an attempt to justify the police raid on the All Russian Co-operative Society, and as a pretext for severance of diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union. Indeed, Britain cut ties later that May.[54]

Flight from China (1927)

On 1 June 1927, Stalin sent a secret telegram to Borodin and M. N. Roy, who was also in Wuhan, ordering the mobilisation of an army of workers and peasants.[55][56] The telegram was discussed at a meeting of the CCP politburo, where it was decried by both Borodin and CCP leaders as an impractical "fairy tale from overseas". Borodin, who was more familiar with Stalin's inner workings, interpreted the instructions as a ploy to relinquish blame for their inevitable failure, whilst Roy thought they signalled a long-awaited quickening of the Chinese revolution. Without consulting anyone, Roy decided to show the telegram to Wang, who was alarmed by its contents.[56][57]

Instead of reassuring Wang, the revelation of the telegram's message drove him to the right, upon which he decided to purge the communists from his administration and reconcile with Chiang Kai-shek. Borodin, along with all other Soviet representatives, was ordered to leave China in July 1927.[58] He refused to leave, however, until his wife, still imprisoned in Jinan, was freed, and was in the meantime harboured by T. V. Soong in his family's house. The Japanese, who considered Shandong within their sphere of influence, bribed a judge to release Fanya on 12 July.[59][60] Formally seen off by the leaders of the Wuhan government, Mikhail left Wuhan by private train on 27 July. He was accompanied on his journey by Sun Yat-sen's widow Soong Ching-ling, Eugene Chen's son Percy Chen, and other Russian and Chinese revolutionary figures.[58][59][60] "The revolution extends to the Yangtze River", Borodin told a reporter as they began their journey, "if a diver were sent down to the bottom of this yellow stream he would rise again with an armful of shattered hopes".[61] He went on to say "When the next Chinese general comes to Moscow and shouts 'Hail to the world revolution', better send at once for the GPU. All that any of them want is rifles".[62] Whilst Fanya made her own way out of country, Borodin, with a bounty on his head, travelled first to Zhengzhou, where he was received by Feng Yuxiang, and then continued through Gansu and across Mongolia to Russia. Though they took different routes, both Mikhail and Fanya arrived in Moscow around the same time in October 1927.[59]

Later life

Borodin and Roy were blamed for the failure of Stalin's China strategy. Upon their arrival in Moscow, Roy was refused an audience with Stalin, and later fled the USSR with Borodin's help. Borodin, on the other hand, was protected by Stalin, and worked a variety of jobs, including deputy director of the Soviet paper and lumber trust, factory inspector, and as a specialist dealing with immigrants from America at the People's Commissariat for Labour.[63][64] In 1931, he reconnected with Anna Louise Strong, with whom he had travelled during his trek out of China.[lower-alpha 3] Strong had earlier expressed the desire to start an English-language Soviet newspaper. With Borodin's help, she founded the Moscow News in 1930.[64] In 1932, Borodin became editor-in-chief of the newspaper.[65] From 1941, he concurrently served as editor-in-chief of the Soviet Information Bureau.[66]

In early 1949, following Strong's attempts to publish a manuscript about the success of Maoism in China, and amidst an antisemitic fervour that had gripped the country following Israel's turn away from the Soviet Union, Borodin and Strong were arrested and the paper shut down. Borodin died two years later on 29 May 1951 at a prison camp near Yakutsk. He was posthumously rehabilitated in 1964.[67][68]

Family

Borodin married Fanya Orluk, known as "Fanny", and originally from Vilnius, in Chicago in 1908.[69] He had two sons, Fred Borodin (Russian: Фёдор Михайлович Бородин) and Norman Borodin, both of whom were American-born. Fred, who rose to the rank of colonel in the Red Army, died during the Second World War, whilst Norman went on to be a Soviet journalist.[70][71]

Influence

Borodin is one of the main characters in André Malraux's 1928 novel Les Conquérants.[72] He also appears in Kenneth Rexroth's poem Another Early Morning Exercise.[73]

Notes

- ↑ Russian: Михаи́л Ма́ркович Грузенберг

- ↑ Russian: Бороди́н, Chinese: 鮑羅廷

- ↑ For a detailed account of that journey, consult the second volume of Anna Louise Strong's 1928 book China's millions.

References

Citations

- ↑ Jacobs 2013, p. 3.

- ↑ Jacobs 2013, pp. 2–6.

- ↑ Jacobs 2013, pp. 7–8, 14–15.

- ↑ Vishni͡akova-Akimova 1971, p. 154.

- ↑ Jacobs 2013, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Jacobs 2013, pp. 28–29, 37.

- ↑ Jacobs 2013, pp. 33–35.

- 1 2 Spenser 2011, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Spence 1990, p. 306.

- 1 2 Foglesong 2014, pp. 276–277.

- ↑ Hagedorn 2007, p. 60.

- ↑ Spenser 2011, p. 44.

- ↑ Spenser 2011, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Spenser 2011, pp. 46–47.

- 1 2 Spenser 2011, pp. 48.

- 1 2 Hopkirk 2001, pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Jacobson 1994, p. 126.

- ↑ The Times 1922, p. 8.

- ↑ Hopkirk 2001, pp. 180–181.

- ↑ Lew & Leung 2013, p. 22.

- ↑ Hopkirk 2001, pp. 179–181.

- ↑ Quốc-Thái (2 April 1947). "Hồ Chí Minh là ai và muốn gì? (I)". Thời Sự. No. 8. Hanoi – via East View Global Press Archive.

- ↑ Soong 1978, p. 180.

- ↑ Hopkirk 2001, p. 181.

- ↑ Chen 2008, p. 106.

- ↑ Spence 1990, p. 336.

- ↑ Spence 1990, pp. 337–338.

- ↑ Wilbur 1983, p. 542.

- 1 2 3 Wilbur 1983, p. 8.

- ↑ Harrison 1972, p. 73.

- ↑ Wilbur 1983, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Spence 1990, p. 338.

- ↑ Chen 2008, p. 111.

- ↑ Fischer 1930, pp. 649–650.

- ↑ Harrison 1972, pp. 72–74.

- 1 2 Fischer 1930, p. 643.

- ↑ Wilbur 1983, p. 557.

- 1 2 Lew & Leung 2013, p. 23.

- ↑ Fischer 1930, p. 650.

- ↑ Jordan 1976, p. 45.

- 1 2 Fischer 1930, pp. 660–661.

- ↑ Fischer 1930, p. 648.

- ↑ Fischer 1930, pp. 661–662.

- ↑ Fischer 1930, pp. 664–665.

- ↑ Jacobson 1994, p. 218.

- 1 2 Jacobson 1994, p. 219.

- ↑ Wilbur & How 1989, p. 392.

- ↑ Vishni͡akova-Akimova 1971, pp. 291–292.

- ↑ Harrison 1972, pp. 108–110.

- ↑ Fischer 1930, pp. 672–674.

- ↑ Hansard, 24 May 1927

- ↑ Hansard, 24 May 1927

- ↑ Hansard, 24 May 1927

- ↑ Andrew 2009, p. 155.

- ↑ Harrison 1972, p. 111.

- 1 2 Jacobs 2013, p. 270.

- ↑ Haithcox 1965, pp. 463–464.

- 1 2 Harrison 1972, p. 115.

- 1 2 3 Wilbur & How 1989, pp. 422–423.

- 1 2 Fischer 1930, p. 676.

- ↑ Spence 1990, pp. 312, 316–317, 324.

- ↑ Brandt 1958, p. 152.

- ↑ Hopkirk 2001, p. 204.

- 1 2 Mickenberg 2017, pp. 168–169.

- ↑ Kirschenbaum 2015, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Draitser 2010, pp. 327–328.

- ↑ Jacobs 2013, pp. 325–326.

- ↑ Shabad 1964.

- ↑ Jacobs 2013, p. 24.

- ↑ Wilbur & How 1989, p. 427.

- ↑ Jacobs 2013, p. 322.

- ↑ Harris 1995, p. 31.

- ↑ Rexroth 1966, pp. 92–93.

Bibliography

- Andrew, Christopher M. (2009). The defence of the realm : the authorized history of MI5. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9885-6. OCLC 421785376.

- Brandt, Conrad (1958). Stalin's Failure in China: 1924-1927. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Chen, Yuan-tsung (2008). Return to the Middle Kingdom: One Family, Three Revolutionaries, and the Birth of Modern China. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 9781402756979.

- Draitser, Emil (2010). Stalin's Romeo Spy: The Remarkable Rise and Fall of the KGB's Most Daring Operative. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 9780810126640.

- Fischer, Louis (1930). The Soviets in World Affairs: A History of Relations Between the Soviet Union and the Rest of the World. Vol. 2. J. Cape. OCLC 59836788.

- Foglesong, David S. (2014). America's Secret War against Bolshevism: U.S. Intervention in the Russian Civil War, 1917-1920. UNC Press Books. ISBN 9781469611136.

- Haithcox, John P. (1965). "Nationalism and Communism in India: The Impact of the 1927 Comintern Failure in China". The Journal of Asian Studies. 24 (3): 459–473. doi:10.2307/2050346. JSTOR 2050346. S2CID 162253132.

- Hagedorn, Ann (2007). Savage Peace: Hope and Fear in America, 1919. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781416539711.

- "Prime Minister's Statement". Hansard. 24 May 1927. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- Harris, G. (1995). André Malraux: A Reassessment. Springer. ISBN 9780230390058.

- Harrison, James Pinckney (1972). The Long March to Power – a History of the Chinese Communist Party, 1921-72. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0333141540.

- Hopkirk, Peter (2001). Setting the East Ablaze: On Secret Service in Bolshevik Asia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192802125.

- Jacobs, Dan (2013). Borodin: Stalin's Man in China. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674184602.

- Jacobson, Jon (1994). When the Soviet Union entered world politics. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91567-1. OCLC 44955883.

- Jordan, Donald A. (1976). The Northern Expedition: China's National Revolution of 1926-1928. University Press of Hawaii. ISBN 9780824803520.

- Kirschenbaum, Lisa A. (2015). International Communism and the Spanish Civil War: Solidarity and Suspicion. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316368923.

- Lew, Christopher R.; Leung, Edwin Pak-wah (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Civil War. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810878747.

- Mickenberg, Julia L. (2017). American Girls in Red Russia: Chasing the Soviet Dream. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226256122.

- Rexroth, Kenneth (1966). The Collected Shorter Poems. New Directions Publishing. ISBN 9780811201780.

- Shabad, Theodore (1 July 1964). "Soviet Rehabilitates Borodin, Aide in China in '20's". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- Soong, Mei-ling (1978). Conversations with Mikhail Borodin. Free Chinese Centre.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1990). The Search for Modern China. Norton. ISBN 9780393934519. - Link to Google Books profile

- Spenser, Daniela (2011). Stumbling Its Way Through Mexico: The Early Years of the Communist International. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 9780817317362.

- Vishni͡akova-Akimova, Vera Vladimirovna (1971). Two Years in Revolutionary China: 1925-1927. Translated by Levine, Steven I. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 9780674916012.

- Wilbur, C. Martin; How, Julie Lien-ying (1989). Missionaries of Revolution: Soviet Advisers and Nationalist China, 1920-1927. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674576520.

- Wilbur, C. Martin (1983). The Nationalist Revolution in China, 1923-1928. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521318648.

- "Foreign Communist Sentenced". The Times. London, England. 30 August 1922. Retrieved 18 October 2018 – via The Times Digital Archive.

Further reading

- Holubnychy, Lydia. Michael Borodin and the Chinese revolution, 1923-1925. 1979;

- Хейфец Л.С. Латинская Америка в орбите Коминтерна. Опыт биографического словаря. М.: ИЛА РАН, 2001;

- Taibo P.I. II. "Los Bolcheviques. Mexico": J.Mortiz, 1986; Martínez Verdugo A. (ed.) Historia del comunismo mexicano. Mexico: Grijalbo, 1985;

- Jeifets L., Jeifets V., Huber P. La Internacional Comunista y América Latina, 1919-1943. Diccionario biográfico. Ginebra: Instituto de Latinoamérica-Institut pour l'histoire du communisme, 2004;

- Kheyfetz L. and V. Michael Borodin. The First Comintern-emissary to Latin America, The International Newsletter of Historical Studies on Comintern, Communism and Stalinism. Vol.II, 1994/95. No.5/6. P.145-149. Vol.III (1996). No.7/8. P.184-188.