| Marathon | |

|---|---|

| |

| RAF Marathon 1953–1958 | |

| Role | Light transport |

| Manufacturer | Handley Page |

| First flight | 19 May 1946 |

| Introduction | 1951 |

| Retired | 1960 |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force West African Airways Corporation |

| Produced | 1946–1951 |

| Number built | 43 |

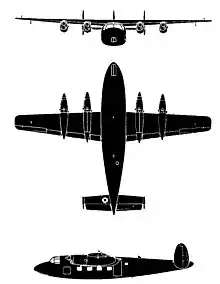

The Handley Page (Reading) H.P.R.1 Marathon was a British four-engined civil transport aircraft, capable of seating up to 20 passengers. It was designed by Miles Aircraft Limited and largely manufactured by Handley Page (Reading) Limited (who acquired Miles' assets) at Woodley Aerodrome, Reading, England.

Originally submitted to the Air Ministry as a four-engined high-wing monoplane weighing roughly 16,500 lb, the concept was well received by the Brabazon Committee, with Miles being issued with instructions to proceed. While development proceeded, various agencies argued over the aircraft's specification, leading to multiple attempts to change the design midway though, delaying progress and inflating costs. Delays over the placement of a firm order contributed to Miles' bankruptcy, after which its assets were acquired by Handley Page and formed into the subsidiary Handley Page (Reading) Limited to produce the Marathon.

The Marathon represented several firsts, being Miles' first four engined aircraft as well as their first all-metal design; it was also recognised that the Marathon was the first British transport aircraft to comply with the stringent International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). However, the lack of commercial involvement in the specification to which the aircraft was built likely heavily contributed to the lukewarm response it received from such operators, with British European Airways (BEA) opting to not introduce the type despite buying seven of them with intentions of doing so. The largest operator of the Marathon was the Royal Air Force, where the type were primarily used as a navigation trainer.

Design and development

Background

The origins of the Marathon are closely associated with the opportunities offered by the Brabazon Committee, which sought to best direct the British aircraft industry's efforts for the postwar civilian market. Work on the project had commenced under Miles Aircraft Limited, having been originally envisioned as a four-engined low-wing cantilever monoplane that was had been intended as a natural successor to the prewar de Havilland Express.[1] Miles' management were convinced that there would be a sizable market for a larger aircraft, but there was some dispute as to how big it should be, with internal proposals ranging from 12,000 lb to 20,000 lb, while some designers pushed for the use of a pair of Bristol-built engines capable of 1,100 hp instead of four de Havilland Gipsy Queen engines producing 330 hp. It was decided to compromise on a four-engined aircraft with a high-mounted wing that weighed roughly 16,500 lb; this proposal was submitted to the Air Ministry for review, resulting in Specification 18/44 being written to fit it.[2][3]

While the concept quickly received the Brabazon Committee's approval, who assigned it the designation Type 5a, Miles did not receive a direct contract immediately; instead, the specification was released to competitive tender during May 1944.[4] While rival bids were submitted from companies such as Percival and Armstrong Whitworth, Miles' design was selected as the winner, with the company being issued an instruction to proceed with development during October 1944. As per the convention at the time, development and ordering were overseen by the Air Ministry alone, with Miles being forbidden from directly communicating with commercial operators to seek input on their requirements or suggestions.[4]

By April 1945, the majority of the design features for the aircraft, which was designated M.60 Marathon, had been agreed upon.[5] The Marathon incorporated numerous modern features, including its all-metal construction, being the first Miles-built aircraft to be built as such, as well as being the company's first four-engined design. Around this latter stage of development, work was protracted by a multitude of state agencies becoming involved and pushing for their own diverse requirements to be incorporated, some of which were contradictory and occasionally impractical to achieve, such as the use of a pressurised cabin or a very high level of structural strength.[6] This led to numerous disputes over which groups had authority to overrule one another and led to considerable resource waste on the project.[7]

Into flight and takeover by Handley Page

A total of three prototypes were built for the development process, the first of which performed the type's maiden flight on 19 May 1946.[5] Flight testing of the Marathon yielded positive results from the onset; during its official trials, the aircraft was described as being the nicest multi-engined aeroplane to have ever been handled by its test pilots. It was also recognised that the Marathon was the first British transport aircraft to comply with the stringent International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) safety requirements.[8] However, on 10 May 1948, tragedy struck when one of the prototypes was lost during official trials held at RAF Boscombe Down; the loss was attributed to pilot error, having failed to adjust the fins to their normal position, resulting in mid-flight structural failure.[8]

While Miles had worked on the Marathon under its instructions to proceed, the issuing of a production contract by British authorities was anything but prompt.[8] The second prototype was in flight and the third was at an advanced stage before negotiations towards such a contract were successful, but by then it was too late for the company. Miles had experienced persistent financial difficulties and was banking on at least 100 Marathons being ordered; however, the initial production contract that emerged only ordered 50 aircraft, of which 30 were intended for British European Airways (BEA) while 20 were directed to British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), which already intended to resell its aircraft onto other airlines.[9]

Furthermore, efforts were made to further develop the aircraft, perhaps most significantly the replacement of its four piston engines with an alternative twin-engine turboprop-driven arrangement; provisions for such a reengining had been made in the Marathon's original design.[10] On 19 May 1947, the Air Ministry issued Specification 15/46 for a turboprop-powered model of the Marathon, leading to formal work commencing immediately thereafter. As per the specification, the new Armstrong Siddeley Mamba was selected to power this variant, but considerations were made for the alternative use of Rolls-Royce Dart engines as well.[11] A single prototype with Mamba engines begun construction in 1947, it performed its first flight during 23 July 1949, at which point it was only the third British aircraft to fly with turboprop engines. The Mamba-powered prototype was later refitted with Alvis Leonides Major radial engines and used to assist development of the projected Handley Page Herald.[12]

Unable to secure relief, the Miles company was forced to declare bankruptcy during late 1947, shortly after which the rival aircraft company Handley Page purchased the majority of its assets, including the firm's factory at Woodley near Reading, Berkshire, along with design rights to the Marathon.[9] Handley Page reorganised its new acquisition as the subsidiary Handley Page (Reading) Limited, and promptly set about produce the Marathon.[9] Somewhat ironically, Handley Page was able to secure a considerably higher sales price for the type that had been asked for by Miles. Between 1948 and 1950, a total of 40 Marathons were manufactured.[13]

Operational history

On 14 January 1950, the first production Marathon 1 aircraft (registered G-ALUB) departed Woodley for a 40,000 mile-long sales tour, reaching Australia and New Zealand.[9] The same aircraft was subsequently painted in BEA markings as "Rob Roy" in September 1951 and was demonstrated to the airline at Heathrow. During acceptance tests for BEA, it was determined that the Marathon was not a suitable replacement for the de Havilland Dragon Rapide, and thus the order was reduced to seven aircraft, none of which was accepted by BEA.[14] According to aviation author Don Brown, BEA had decided on cancelling its plans to introduce the Marathon during February 1952, largely as a result of government authorities having failed to consider the airline's requirements.[9]

Six Marathons were delivered to the West African Airways Corporation in late 1952 for operation in and between the British colonies in that region.[13] The type were entirely replaced during 1954 by de Havilland Herons. The last three production aircraft were given increased tankage and sold to Union of Burma Airways which operated them in the region for several years.[15]

The Ministry of Supply ended up with as many as 30 returned or unsold Marathons, and promptly sought out uses for them.[9] The majority of excess aircraft were diverted for use by the Royal Air Force as navigation trainers, receiving the designation Marathon T.11 along with numerous internal modifications to suit the role. Many of the 28 aircraft taken on charge from early 1953 were flown by No. 2 Air Navigation School at RAF Thorney Island, Hants. A total of 16 aircraft were transferred to RAF Topcliffe, Yorks in June 1958 when No.1 Air Navigation School relocated there. By February 1959, only eight were airworthy. Apart from mechanical unreliability, the Marathon reportedly possessed a relatively tail-heavy trim, an absolute ceiling of 9,500 feet, and a rate of climb of only 300 ft a minute. The last of the Marathon navigational trainers were retired in April 1959, after which the majority were quickly scrapped.[16][17] A few Marathons were operated by other UK military users, including the Royal Aircraft Establishment.

Three Marathons were acquired in 1955 by Derby Aviation, based at Burnaston airport near Derby and predecessor of British Midland Airways. The aircraft were used on scheduled services within the UK and to the Channel Islands until their withdrawal in December 1960. Two aircraft (G-ALVY/XA252 and G-AMER/XA261) were returned from the RAF to F.G. Miles at Shoreham for planned use on scheduled services but this failed to happen and they were scrapped in 1962. One aircraft was delivered to Jordan in September 1954 for the personal use of King Hussein.

No surviving airframes are known to exist but the upper fuselage section of Marathon M.60 G-AMGW was stored at Woodley, United Kingdom as part of the Miles Collection c. 2000[18]

Variants

- M.60 Marathon

- Miles-built prototypes, two built.

- Miles M.69 Marathon II

- Miles-built version powered by Mamba engines created for British European Airways, only one prototype built.

- Marathon

- Miles M.69 re-engined by Handley Page and used as an engine testbed.

- Marathon I

- Handley Page-built production aircraft, 40 built.

- Marathon T.11

- Military navigation trainer version, 28 modified.

Operators

Civil operators

- British European Airways (not operated on passenger services)[19]

- Derby Aviation[19]

Military and government operators

- West German Government[19]

Accidents and incidents

- 10 May 1948 – Prototype G-AGPD being operated by the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment crashed near Amesbury, Wiltshire, United Kingdom.[19]

- 4 August 1953 – XY-ACX a Union of Burma Airways Marathon 1A was damaged beyond repair at Myaungmya, Burma.[19]

- 30 September 1954 – XA271 a Royal Air Force Marathon T11 crashed after inflight structural failure near Calne, Wiltshire, United Kingdom.[19][20]

- 9 January 1956 – XA254 a Royal Air Force Marathon T11 was damaged beyond repair when it overran the runway at RAF Topcliffe, the landing gear was retracted in an attempt to stop the aircraft.[20]

- 30 October 1957 – XA256 a Royal Air Force Marathon T11 was damaged beyond repair after the landing gear collapsed in a hangar at RAF Thorney Island.[19][20]

- 16 November 1957 – XA251 a Royal Air Force Marathon T11 was damaged beyond repair.[19]

- 10 December 1957 – XA250 a Royal Air Force Marathon T11 was damaged beyond repair during a landing accident. Landing-gear leg jammed and collapsed on landing at RAF Topcliffe, Yorkshire, United Kingdom.[19][20]

- 11 February 1958 – XA268 a Royal Air Force Marathon T11 was damaged beyond repair landing at RAF Topcliffe when the nosewheel became detached.[19][20]

- 22 April 1958 – XA273 a Royal Air Force Marathon T11 was damaged beyond repair after the landing gear collapsed at RAF Topcliffe.[19]

- 5 May 1958 – XA253 a Royal Air Force Marathon T11 was damaged beyond repair when the landing gear was retracted in error for the flaps on the ground at RAF Topcliffe.[19][20]

Specifications (Marathon 1)

Data from British Civil Aircraft since 1919: Volume 2.[21]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Capacity: 20 passengers

- Length: 52 ft 1+1⁄2 in (15.888 m)

- Wingspan: 65 ft 0 in (19.81 m)

- Height: 14 ft 1 in (4.29 m)

- Wing area: 498 sq ft (46.3 m2)

- Airfoil: NACA 23018 (root), NACA 230009 (tip)[22]

- Empty weight: 11,688 lb (5,302 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 18,250 lb (8,278 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 240 imp gal (290 US gal; 1,100 L) normal[22]

- Powerplant: 4 × de Havilland Gipsy Queen 70-3 six-cylinder air-cooled inline piston engine, 340 hp (250 kW) each

Performance

See also

Related lists

References

Citations

- ↑ Brown 1970, p. 301.

- ↑ Brown 1970, pp. 301-302.

- ↑ Thetford 1976, p. 285.

- 1 2 Brown 1970, p. 302.

- 1 2 Brown 1970, p. 303.

- ↑ Brown 1970, pp. 303-304.

- ↑ Brown 1970, pp. 304-305.

- 1 2 3 Brown 1970, p. 305.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Brown 1970, p. 306.

- ↑ Brown 1970, p. 333.

- ↑ Brown 1970, pp. 333-334.

- ↑ Brown 1970, p. 334.

- 1 2 Brown 1970, p. 307.

- ↑ Jackson 1973, pp. 253–254.

- ↑ Jackson 1973, pp. 254–255.

- ↑ Thetford 1976, p. 307.

- ↑ Wilson 2015, p. 118.

- ↑ "A Conundrum". f-86.tripod.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Eastwood and Roach 1991, pp. 277–278.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Halley 2001, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Jackson 1973, pp. 252, 256.

- 1 2 3 4 Bridgman 1951, pp. 63c–64c.

Bibliography

- Amos, Peter. and Don Lambert Brown. Miles Aircraft Since 1925, Volume 1. London: Putnam Aeronautical, 2000. ISBN 0-85177-787-2.

- Bridgman, Leonard. Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1951–52. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, Ltd., 1951.

- Brown, Don Lambert. Miles Aircraft Since 1925. London: Putnam & Company Ltd., 1970. ISBN 0-370-00127-3.

- Eastwood, Tony. and Roach, John Piston Engine Airliner Production List. West Drayton, UK: Aviation Hobby Shop, 1991. ISBN 0-907178-37-5.

- Hailey, James J. (compiler). Royal Air Force Aircraft XA100 to ZA999. Tonbridge, Kent, UK: Air Britain (Historians) Ltd., 2001. ISBN 0-85130-311-0

- The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft (Part Work 1982–1985). London: Orbis Publishing, 1985.

- Jackson, A.J. British Civil Aircraft since 1919, Volume 2. London: Putnam & Company Ltd., 1973. ISBN 0-370-10010-7.

- Temple, Julian C. Wings Over Woodley: The Story of Miles Aircraft and the Adwest Group. Bourne End, Bucks, UK: Aston Publications, 1987. ISBN 0-946627-12-6.

- Thetford, Owen. Aircraft of the Royal Air Force since 1918. London: Putnam & Company Limited, 1976. ISBN 0-370-10056-5.

- Wilson, Keith. RAF in Camera: 1950s. Pen & Sword Books Limited, 2015. ISBN 1-4738-2795-7.