44°49′N 20°27′E / 44.817°N 20.450°E

Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia Gebiet des Militärbefehlshabers in Serbien | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1941–1944 | |||||||||

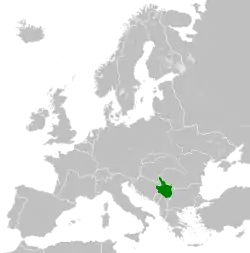

The Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia within Europe, circa 1942 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Territory under German military administration | ||||||||

| Capital | Belgrade | ||||||||

| Common languages | German Serbian | ||||||||

| Government | Military government[a] | ||||||||

| Military Commander | |||||||||

• Apr–Jun 1941 | Helmuth Förster | ||||||||

• Jun–Jul 1941 | Ludwig von Schröder | ||||||||

• Jul–Sep 1941 | Heinrich Danckelmann | ||||||||

• Sep–Dec 1941 | Franz Böhme | ||||||||

• 1941–1943 | Paul Bader | ||||||||

• 1943–1944 | Hans Felber | ||||||||

| Prime Minister (of puppet government) | |||||||||

• 1941 | Milan Aćimović | ||||||||

• 1941–1944 | Milan Nedić | ||||||||

| Historical era | World War II | ||||||||

• Established | 22 April 1941 | ||||||||

| 20 October 1944 | |||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1941[1] | 4,500,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | Serbian dinar Reich credit note | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Serbia Kosovo[b] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of Serbia |

|---|

|

|

|

The Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia (German: Gebiet des Militärbefehlshabers in Serbien; Serbian: Подручје Војног заповедника у Србији, romanized: Područje vojnog zapovednika u Srbiji) was the area of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia that was placed under a military government of occupation by the Wehrmacht following the invasion, occupation and dismantling of Yugoslavia in April 1941. The territory included only most of modern central Serbia, with the addition of the northern part of Kosovo (around Kosovska Mitrovica), and the Banat. This territory was the only area of partitioned Yugoslavia in which the German occupants established a military government. This was due to the key rail and the Danube transport routes that passed through it, and its valuable resources, particularly non-ferrous metals.[3] On 22 April 1941, the territory was placed under the supreme authority of the German military commander in Serbia, with the day-to-day administration of the territory under the control of the chief of the military administration staff. The lines of command and control in the occupied territory were never unified, and were made more complex by the appointment of direct representatives of senior Nazi figures such as Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler (for police and security matters), Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring (for the economy), and Reichsminister Joachim von Ribbentrop (for foreign affairs). The Germans used Bulgarian troops to assist in the occupation, but they were at all times under German control. Sources variously describe the territory as a puppet state, a protectorate, a "special administrative province", or describe it as having a puppet government. The military commander in Serbia had very limited German garrison troops and police detachments to maintain order, but could request assistance from a corps of three divisions of poorly-equipped occupation troops.

The German military commander in Serbia appointed two Serbian civil puppet governments to carry out administrative tasks in accordance with German direction and supervision. The first of these was the short-lived Commissioner Government which was established on 30 May 1941. The Commissioner Government was a basic tool of the occupation regime, lacking in any powers. In late July 1941, an uprising began in the occupied territory, which quickly swamped the Serbian gendarmerie, German police and security apparatus, and even the rear area infantry force. To assist in quelling the rebellion, which initially involved both the communist-led Yugoslav Partisans and the monarchist Chetniks, a second puppet government was established. The Government of National Salvation under Milan Nedić replaced the Commissioner Government on 29 August 1941. Although it enjoyed some support,[4] the regime was unpopular with the majority of Serbs.[5] This failed to turn the tide however, and the Germans were forced to bring in front line divisions from France, Greece and even the Eastern Front to suppress the revolt. Commencing from late September 1941, Operation Uzice expelled the Partisans from the occupied territory, and in December, Operation Mihailovic dispersed the Chetniks. Resistance continued at a low level until 1944, accompanied by frequent reprisal killings, which for some time involved the execution of 100 hostages for every German killed.

The Nedić regime had no status under international law, no powers beyond those granted by the Germans, and was simply an instrument of German rule. Although German forces took the leading and guiding role of the Final Solution in Serbia, and the Germans monopolized the killing of Jews, they were actively aided in that role by Serbian collaborators.[6] The Banjica concentration camp in Belgrade was jointly controlled by Nedic's regime and the German army. The one area in which the puppet administration did exercise initiative and achieve success was in the reception and care of hundreds of thousands of Serb refugees from other parts of partitioned Yugoslavia. Throughout the occupation, the Banat was an autonomous region, formally responsible to the puppet governments in Belgrade, but in practice governed by its Volksdeutsche (ethnic German) minority. While the Commissioner Government was limited to the use of gendarmerie, the Nedić government was authorized to raise an armed force, the Serbian State Guard, to impose order, but they were immediately placed under the control of the Higher SS and Police Leader, and essentially functioned as German auxiliaries until the German withdrawal in October 1944. The Germans also raised several other local auxiliary forces for various purposes within the territory. In order to secure the Trepča mines and the Belgrade-Skopje railway, the Germans made an arrangement with Albanian collaborators in the northern tip of present-day Kosovo which resulted in the effective autonomy of the region from the puppet government in Belgrade, which later formalized the German arrangement. The Government of National Salvation remained in place until the German withdrawal in the face of the combined Red Army, Bulgarian People's Army and Partisan Belgrade Offensive. During the occupation, the German authorities killed nearly all Jews residing in the occupied territory, by shooting the men as part of reprisals conducted in 1941, and gassing the women and children in early 1942 using a gas van. After the war, several of the key German and Serbian leaders in the occupied territory were tried and executed for war crimes.

Names

While the official name of the territory was Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia,[7] sources refer to it using a wide variety of terms:

- a German-controlled "Serbian Residual State"[8]

- a German-controlled territory[1]

- a rump Serbian state[9]

- a "so-called German protectorate"[10]

- a special "German-protected area"[11]

- German-occupied Serbia[12][13]

- Nedić's Serbia[14] (Serbian: Недићева Србија/Nedićeva Srbija)[15]

- Serbia[3]

- Serbia–Banat[16]

- Serbia under German military administration[17]

- Serbia under German occupation[18][19]

History

1941

Invasion and partition

In April 1941, Germany and its allies invaded and occupied the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, which was then partitioned. Some Yugoslav territory was annexed by its Axis neighbors, Hungary, Bulgaria and Italy. The Germans engineered and supported the creation of the puppet state, the Independent State of Croatia (Croatian: Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH), which roughly comprised most of the pre-war Banovina Croatia, along with the rest of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina and some adjacent territory. The Italians, Hungarians and Bulgarians occupied other parts of Yugoslavian territory.[20] Germany did not annex any Yugoslav territory, but occupied northern parts of present-day Slovenia and stationed occupation troops in the northern half of the NDH. The German-occupied part of Slovenia was divided into two administrative areas that were placed under the administration of the Gauleiters of the neighboring Reichsgau Kärnten and Reichsgau Steiermark.[21]

The remaining territory, which consisted of Serbia proper, the northern part of Kosovo (around Kosovska Mitrovica), and the Banat was occupied by the Germans and placed under the administration of a German military government.[11] This was due to the key rail and riverine transport routes that passed through it, and its valuable resources, particularly non-ferrous metals.[20] Some sources describe the territory as a puppet state,[22] or a "special administrative province",[23] with other sources describing it as having a puppet government.[1][24] A demarcation line, known as the "Vienna Line", ran across Yugoslavia from the Reich border in the west to the point where the boundaries of German-occupied Serbia met the borders of the Bulgarian- and Albanian-annexed Yugoslavian territories. To the north of the line, the Germans held sway, with the Italians having prime responsibility to the south of the line.[25]

Establishment of the military government of occupation

Even before the Yugoslav surrender, the German Army High Command (German: Oberkommando des Heeres, or OKH) had issued a proclamation to the population under German occupation,[26] detailing laws that applied to all German-occupied territory. When the Germans withdrew from the Yugoslav territory that was annexed or occupied by their Axis partners, these laws applied only to the part of modern-day Slovenia administered by the two Reichsgau, and the German-occupied territory of Serbia.[27] This latter territory "was occupied outright by German troops and was placed under a military government".[25] The exact boundaries of the occupied territory were fixed in a directive issued by Adolf Hitler on 12 April 1941, which also directed the creation of the military administration.[11] This directive was followed up on 20 April 1941 by orders issued by the Chief of the OKH which established the Military Commander in Serbia as the head of the occupation regime, responsible to the Quartermaster-General of the OKH. In the interim, the staff for the military government had been assembled in Germany and the duties of the Military Commander in Serbia had been detailed. These included "safeguarding the railroad lines between Belgrade and Salonika and the Danube shipping route, executing the economic orders issued [by Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring], and establishing and maintaining peace and order". In the short-term, he was also responsible for guarding the huge numbers of Yugoslav prisoners of war, and safeguarding captured weapons and munitions.[28]

In order to achieve this the military commander's staff was divided into military and administrative branches, and he was allocated personnel to form four area commands and about ten district commands, which reported to the chief of the administrative staff, and the military staff allocated the troops of the four local defence battalions across the area commands. The first military commander in the occupied territory was General der Flieger[lower-alpha 1] Helmuth Förster, a Luftwaffe officer, appointed on 20 April 1941,[30] assisted by the chief of the administrative staff, SS-Brigadeführer[lower-alpha 2] and State Councillor, Dr. Harald Turner.[31] Outside of the military commander's staff, there were several senior figures in Belgrade who represented key non-military arms of the German government. Prominent among these was NSFK-Obergruppenführer, Franz Neuhausen, who was initially appointed by Göring as plenipotentiary general for economic affairs in the territory on 17 April.[32][33] Another was Envoy Felix Benzler of the Foreign Office, appointed by Reichsminister Joachim von Ribbentrop who was appointed on 3 May.[24] A further key figure in the initial German administration was SS-Standartenführer Wilhelm Fuchs, who commanded Einsatzgruppe Serbia, consisting of Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service, or SD) and Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police, or SiPo), the 64th Reserve Police Battalion,[34] and a detachment of Gestapo. While he was formally responsible to Turner, Fuchs reported directly to his superiors in Berlin.[24] The proclamations of the Chief of the OKH in April ordered severe punishments for acts of violence or sabotage, the surrender of all weapons and radio transmitters, restrictions on communication, meetings and protests, and the requirement for German currency to be accepted, as well as imposing German criminal law on the territory.[26]

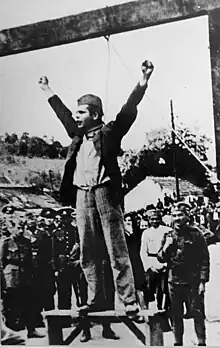

In a sign of things to come, on the day after the capitulation of Yugoslavia, the SS Motorised Infantry Division Reich had executed 36 Serbs in reprisal for the killing of one member of that formation. Three days later, the village of Donji Dobrić just east of the Drina river had been razed in response to the killing of a German officer. The killing of German troops after the capitulation drew a strong reaction from the commander of the German 2nd Army, Generaloberst Maximilian von Weichs, who ordered that whenever an armed group was seen, men of fighting age from that area were to be rounded up and shot, with their bodies hung up in public, unless they were able to prove they had no connection to the armed group. He also directed the taking of hostages. On 19 May, he issued an ominous decree, ordering that from that point on, 100 Serbs were to be shot for every German soldier that was harmed in any Serb attack.[35] Almost as soon as the success of the invasion was assured, all front line German corps and divisions began to be withdrawn from Yugoslavia to be reconditioned or directly allocated to the Eastern Front.[36]

Preparations of the Communist Party

On 10 April, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (Serbo-Croatian Latin: Komunistička partija Jugoslavije, KPJ) had appointed a military committee headed by its secretary-general, Josip Broz Tito.[37] From April, the KPJ had an underground network right across the country, including military committees that were preparing for an opportunity to initiate a revolt.[38] In May, the KPJ outlined its policy of "unity and brotherhood among all peoples of Yugoslavia, [and] relentless struggle against the foreign enemies and their domestic helpers as a matter of sheer survival".[39] On 4 June, the military committee was titled Partisan Chief Headquarters.

Early activities of Draža Mihailović

In late April, Yugoslav Army Colonel Draža Mihailović and a group of about 80 soldiers, who had not followed the orders to surrender, crossed the Drina river into the occupied territory, having marched cross-country from the area of Doboj, in northern Bosnia, which was now part of the NDH. As they passed near Užice on 6 May, the small group was surrounded and almost destroyed by German troops. His force fragmented, and when he reached the isolated mountain plateau of Ravna Gora, his band had shrunk to 34 officers and men. By establishing ties with the local people, and toleration by the gendarmerie in the area, Mihailović created a relatively safe area in which he could consider his future actions.[40] Soon after arriving at Ravna Gora, Mihailović's troops took the name "Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army".[41] By the end of May, Mihailović had decided that he would adopt a long-term strategy aimed at gaining control over as many armed groups as possible throughout Yugoslavia, in order to be in a position to seize power when the Germans withdrew or were defeated.[42]

Establishment of the Commissioner Government

.jpg.webp)

Hitler had briefly considered erasing all existence of a Serbian state, but this was quickly abandoned and a search began for a suitable Serb to lead a collaborationist regime. Consideration was given to appointing former Yugoslav Prime Minister Dragiša Cvetković, former Yugoslav Foreign Minister Aleksandar Cincar-Marković, former Yugoslav Minister of Internal Affairs Milan Aćimović, the president of the 'quasi-fascist' United Active Labour Organization (Serbian: Združena borbena organizacija rada, or Zbor) Dimitrije Ljotić, and the Belgrade police chief Dragomir Jovanović.[43] Förster decided on Aćimović, who formed his Commissioner Government (Serbian: Komesarska vlada) on 30 May 1941,[44] consisting of ten commissioners. He avoided Ljotić as he believed he had a 'dubious reputation among Serbs'.[43] Aćimović was virulently anti-communist and had been in contact with the German police before the war.[44] The other nine commissioners were Steven Ivanić, Momčilo Janković, Risto Jojić, Stanislav Josifović, Lazo M. Kostić, Dušan Letica, Dušan Pantić, Jevrem Protić and Milisav Vasiljević, and one commissioner was in charge of each of the former Yugoslav ministries except the Ministry of Army and Navy which was abolished.[44] Several of the commissioners had held ministerial posts in the pre-war Yugoslav government, and Ivanić and Vasiljević were both closely linked to Zbor.[45] The Commissioner Government was "a low-grade Serbian administration... under the control of Turner and Neuhausen, as a simple instrument of the occupation regime",[46] that "lacked any semblance of power".[45] Soon after the formation of the Aćimović administration, Mihailović sent a junior officer to Belgrade to advise Ljotić of his progress, and to provide assurances that he had no plans to attack the Germans.[47]

One of the first tasks of the administration was to carry out Turner's orders for the registration of all Jews and Romani in the occupied territory and implementation of severe restrictions on their activities. While the implementation of these orders was supervised by the German military government, Aćimović and his interior ministry were responsible for carrying them out.[48] The primary means for the carrying out of such tasks was the Serbian gendarmerie, which was based on elements of the former Yugoslav gendarmerie units remaining in the territory,[49] the Drinski and Dunavski regiments.[50] The acting head of the Serbian gendarmerie was Colonel Jovan Trišić.[49]

During May 1941, Förster issued numerous orders, which included a requirement for the registration of all printing equipment, restrictions on the press, operation of theatres and other places of entertainment, and the resumption of production. He also disestablished the National Bank of Yugoslavia, and established the Serbian National Bank to replace it.[51] In mid-May, Aćimović's administration issued a declaration to the effect that the Serbian people wanted "sincere and loyal cooperation with their great neighbor, the German people". Most of the local administrators in the formerly Yugoslav counties and districts remained in place,[52] and the German military administration placed its own administrators at each level to supervise the local authorities.[53] Förster was subsequently transferred to command Fliegerkorps I, and on 2 June was succeeded by General der Flakartillerie[lower-alpha 3] Ludwig von Schröder, another Luftwaffe officer.[30] On 9 June, the commander of the German 12th Army, Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm List, was appointed as the Wehrmacht Commander-in-Chief Southeast Europe. Three territorial commanders reported directly to him; Schröder, the Military Commander in the Saloniki-Aegean Area, and the Military Commander in Southern Greece.[54] After the withdrawal of all front line formations from Yugoslavia, the only front line formations remaining under the control of List's headquarters in Salonika were; the Headquarters of XVIII Army Corps of General der Gebirgstruppe Franz Böhme, the 5th Mountain Division on Crete, the 6th Mountain Division in the Attica region around Athens, and the 164th Infantry Division and 125th Infantry Regiment in Salonika and on the Aegean Islands.[36]

Initial German occupation troops

Military Commander in Serbia

From his headquarters in Belgrade, Schröder directly controlled four poorly-equipped local defence (German: Landesschützen) battalions, consisting of older age men. In late June, they were deployed as follows:[55]

- 266th Landesschützen Battalion, headquartered at Užice in the west

- 562nd Landesschützen Battalion, headquartered at Belgrade

- 592nd Landesschützen Battalion, headquartered at Pančevo in the southern Banat

- 920th Landesschützen Battalion, headquartered at Niš in the south

These occupation forces were supplemented by a range of force elements, including the 64th Reserve Police Battalion of the Ordnungspolizei (Order Police, Orpo), an engineer regiment consisting of a pioneer battalion, a bridging column and a construction battalion, and several military police units, comprising a Feldgendarmerie (military police) company, a Geheime Feldpolizei (secret field police) group, and a prisoner of war processing unit. The occupation force was also supported by a military hospital and ambulances, veterinary hospital and ambulances, general transport column, and logistic units.[55]

The chief of the military administrative staff was responsible for the staffing of the four area commands and nine district commands in the occupied territory. In late June 1941, these comprised:[55]

Area Commands

- Area Command No. 599 Belgrade

- Area Command No. 610 Pančevo

- Area Command No. 809 Niš

- Area Command No. 816 Užice

District Commands

- District Command No. 823 Petrovgrad (today Zrenjanin)

- District Command No. 832 Kragujevac

- District Command No. 833 Kruševac

- District Command No. 834 Belgrade

- District Command No. 838 Zemun (Semlin in German)

- District Command No. 847 Šabac

- District Command No. 857 Zaječar

- District Command No. 861 Kosovska Mitrovica

- District Command No. 867 Leskovac

LXV Corps ZbV

In addition to the occupation troops directly commanded by Schröder, in June 1941 the Wehrmacht deployed the headquarters of the LXV Corps zbV[lower-alpha 4] to Belgrade to command four poorly-equipped occupation divisions, under the control of General der Artillerie[lower-alpha 5] Paul Bader. The 704th Infantry Division, 714th Infantry Division and 717th Infantry Division were deployed in the occupied territory, and the 718th Infantry Division was deployed in the adjacent parts of the NDH.[56]

The three occupation divisions had been raised during the spring of 1941, as part of the German Army's 15th Wave of conscription. The 704th was raised from the Dresden military district, the 714th from Königsberg, and the 717th from Salzburg.[57] The 15th Wave divisions consisted of just two infantry regiments, one less than front line divisions, with each regiment comprising three battalions of four companies each. Each company was equipped with just one light mortar, rather than the usual three.[58] The supporting arms of these divisions, such as engineer and signals elements, were only of company size, rather than the battalion-strength elements included in front line formations. Their supporting elements did not include medium mortars, medium machine guns, or anti-tank or infantry guns.[57] Even their artillery was limited to a battalion of three batteries of four guns each,[58] rather than a full regiment,[57] and the divisions were short of all aspects of motorized transport, including spare tyres.[59]

The 15th Wave divisions were usually equipped with captured motor vehicles and weapons,[58] and were formed using reservists, usually older men not suitable for front line service, whose training was incomplete.[57] The commanders at battalion and company level were generally veterans of World War I, and platoon commanders usually between 27 and 37 years old. The troops were conscripted from those born between 1907 and 1913, so they ranged from 28 to 34 years of age.[59] The three divisions had been transported to the occupied territory between 7 and 24 May, and were initially tasked with guarding the key railway lines to Bulgaria and Greece.[57]

By late June, Bader's headquarters had been established in Belgrade, and the three divisions in the occupied territory were deployed as follows:[60]

- 704th Infantry Division, commanded by Generalmajor[lower-alpha 6] Heinrich Borowski, headquartered at Valjevo in the west

- 714th Infantry Division, commanded by Generalmajor Friedrich Stahl, headquartered at Topola roughly in the centre of the territory

- 717th Infantry Division, commanded by Generalmajor Paul Hoffmann, headquartered at Niš

The status of Bader's command was that the military commander in Serbia could order him to undertake operations against rebels, but he could not otherwise act as Bader's superior.[61] Bader's command also included the 12th Panzer Company zbV, initially equipped with about 30 captured Yugoslav Renault FT tankettes, and a motorized signals battalion.[60] The four Landesschützen battalions fell far short of the numbers needed for guarding tasks throughout the territory, which included; bridges, factories, mines, arms dumps of captured weapons, and shipping on the Danube. Consequently, the battalions of the occupation divisions were given many of these tasks, and were in some cases stationed 120 kilometres (75 mi) apart, linked by poor roads and hampered by a lack of transport.[59]

Difficulties of the Aćimović administration

While the commissioners were quite experienced in their portfolio areas or in politics or public administration generally, the Aćimović administration itself was in an extremely difficult position because it lacked any power to actually govern. The three main tasks of the Aćimović administration were to secure the acquiescence of the population to the German occupation, help restore services, and "identify and remove undesirables from public services".[46] Refugees escaping persecution in the Independent State of Croatia, and others fleeing Bulgarian-annexed Macedonia, Kosovo and Hungarian-occupied Bačka and Baranja had begun to flood into the territory.[45]

In late June 1941, the Aćimović administration issued an ordinance regarding the administration of the Banat which essentially made the region a separate civil administrative unit under the control of the local Volksdeutsche under the leadership of Sepp Janko. While the Banat was formally under the jurisdiction of the Aćimović administration, in practical terms it was largely autonomous of Belgrade and under the direction of the military government through the military area command in Pančevo.[62][63]

Resistance begins

In early July 1941, shortly after the launching of Operation Barbarossa against the Soviet Union, armed resistance began against both the Germans and the Aćimović authorities.[45] This was a response to appeals from both Joseph Stalin and the Communist International for communist organisations across occupied Europe to draw German troops away from the Eastern Front, and followed a meeting of the Central Committee of the Yugoslav Communist Party in Belgrade on 4 July. This meeting resolved to shift to a general uprising, form Partisan detachments of fighters and commence armed resistance, and call for the populace to rise up against the occupiers throughout Yugoslavia.[38] This also coincided with the departure of the last of the German invasion force that had remained to oversee the transition to occupation. From the appearance of posters and pamphlets urging the population to undertake sabotage, it rapidly turned to attempted and actual sabotage of German propaganda facilities and railway and telephone lines.[64] The first fighting occurred at the village of Bela Crkva on 7 July, when gendarmes tried to disperse a public meeting, and two gendarmes were killed.[38] At the end of the first week in July, List requested the Luftwaffe transfer a training school to the territory, as operational units were not available.[65] Soon after, gendarmerie stations and patrols were being attacked, and German vehicles were fired upon. Armed groups first appeared in the Aranđelovac district, northwest of Topola.[64]

On 10 July, Aćimović's administration was re-organized, with Ranislav Avramović replacing Kostić in the transportation portfolio, Budimir Cvijanović replacing Protić in the food and agriculture area, and Velibor Jonić taking over the education portfolio from Jojić.[66]

In mid-July, Mihailović sent Lieutenant Neško Nedić to meet with a representative of Aćimović's to ensure he was aware that Mihailović's forces had nothing to do with the "communist terror". The Germans then encouraged Aćimović to make an arrangement with Mihailović, but Mihailović refused. Nevertheless, neither the Germans nor Aćimović took effective action against Mihailović during the summer.[67] On 17 July, Einsatzgruppe Serbien personnel were distributed among the four area commands as "security advisors". The following day, Generalmajor Adalbert Lontschar, commander of the 704th Infantry Division's 724th Infantry Regiment was travelling from Valjevo when his staff car was fired on near the village of Razna, wounding one occupant. In response, the district command executed 52 Jews, communists and others, with the assistance of the Serbian gendarmerie and Einsatzgruppe Serbia.[68] Also in July, the German military government ordered the Jewish community representatives to supply 40 hostages each week who would be executed as reprisals for attacks on the Wehrmacht and German police. Subsequently, when reprisal killings of hostages were announced, most referred to the killing of "communists and Jews".[69]

In late July, Schröder died after being injured in an aircraft accident.[56] When the new German Military Commander in Serbia, Luftwaffe General der Flieger Heinrich Danckelmann, was unable to obtain more German troops or police to suppress the revolt, he had to consider every option available. As Danckelmann had been told to utilise available forces as ruthlessly as possible, Turner suggested that Danckelmann strengthen the Aćimović administration so that it might subdue the rebellion itself.[70] The Germans considered the Aćimović administration incompetent and by mid-July were already discussing replacing Aćimović.[71] On 29 July, in reprisal for an arson attack on German transport in Belgrade by a 16-year-old Jewish boy, Einsatzgruppe Serbien executed 100 Jews and 22 communists.[72] By August, around 100,000 Serbs had crossed into the occupied territory from the NDH, fleeing persecution by the Ustaše.[73] They were joined by more than 37,000 refugees from Hungarian-occupied Bačka and Baranja, and 20,000 from Bulgarian-annexed Macedonia.[74] At the end of July, two battalions of the 721st Regiment of the 704th Infantry Division were sent to suppress rebels in the Banat region, who had destroyed large wheat stores in the Petrovgrad district. Such interventions were not successful, as the occupation divisions lacked the mobility and training for counter-insurgency.[75]

On 4 August, Danckelmann requested that the OKW reinforce his administration with two additional police battalions and another 200 SD security personnel. This was rebuffed due to the needs of the Eastern Front, but before he had received a reply, he had made a request for an additional Landesschützen battalion, and had asked List for an additional division.[76] List had supported the requests for more Landesschützen battalions, so on 9 August OKH authorized the raising of two additional companies for the Belgrade-based 562nd Landesschützen Battalion.[77] On 11 August, unable to obtain significant reinforcements from elsewhere, Danckelmann ordered Bader to put down the revolt, and two days later Bader issued orders to that effect.[78]

Appeal to the Serbian Nation

In response to the revolt, the Aćimović administration encouraged 545 or 546 prominent and influential Serbs to sign the Appeal to the Serbian Nation, which was published in the German-authorized Belgrade daily newspaper Novo vreme on 13 and 14 August.[79][lower-alpha 7] Those that signed included three Serbian Orthodox bishops, four archpriests, and at least 81 professors from the University of Belgrade,[83] although according to the historian Stevan K. Pavlowitch, many of the signatories were placed under pressure to sign.[84] The appeal called upon the Serbian population to help the authorities in every way in their struggle against the communist rebels, and called for loyalty to the Nazis, condemning the Partisan-led resistance as unpatriotic. The Serbian Bar Association unanimously supported the Appeal.[70] Aćimović also gave orders that the wives of communists and their sons older than 16 years of age be arrested and held, and the Germans burned their houses and imposed curfews.[52]

Resistance intensifies

On 13 August, Bader reneged on Danckelmann's pledge to allow the Commissioner Government to maintain control the Serbian gendarmerie, and ordered that they be re-organized into units of 50 to 100 men under the direction of local German commanders.[85] He also directed the three divisional commanders to have their battalions form Jagdkommandos, lightly armed and mobile "hunter teams", incorporating elements of Einsatzgruppe Serbien and the gendarmerie.[68] The following day, the Aćimović administration appealed for rebels to return to their homes and announced bounties for the killing of rebels and their leaders.[70]

The Aćimović administration had suffered 246 attacks between 1 July and 15 August, killing 82 rebels for the loss of 26. The Germans began shooting hostages and burning villages in response to attacks.[70] On 17 August, a company of the 704th Infantry Division's 724th Infantry Regiment killed 15 communists in fighting near Užice, then shot another 23 they rounded up on suspicion they were smuggling provisions to interned communists. The bodies of 19 of the executed men were hung at the Užice railway station.[68] At the end of August, the Salonika-based 164th Infantry Division's 433rd Infantry Regiment was ordered to detach a battalion to Bader's command.[86] During August, there were 242 attacks on the Serbian administration and gendarmerie, as well as railway lines, telephone wires, mines and factories. The Belgrade-Užice-Ćuprija-Paraćin-Zaječar railway line was hardest hit.[87] A sign of the rapid escalation of the revolt was that 135 of the attacks occurred in the last 10 days of the month.[88] The German troops themselves had lost 22 killed and 17 wounded. By the end of the month, the number of communists and Jews shot or hanged had reached 1,000.[89] The number of Partisans in the territory had grown to around 14,000 by August.[90]

To strengthen the puppet government, Danckelmann wanted to find a Serb who was both well-known and highly regarded by the population who could raise some sort of Serbian armed force and who would be willing to use it ruthlessly against the rebels whilst remaining under full German control. These ideas ultimately resulted in the replacement of the entire Aćimović administration at the end of August 1941.[70]

Formation of the Government of National Salvation

In response to a request from Benzler, the Foreign Office sent SS-Standartenführer Edmund Veesenmayer to provide assistance in establishing a new puppet government that would meet German requirements.[91] Five months earlier, Veesenmayer had engineered the proclamation of the NDH.[92] Veesenmayer engaged in a series of consultations with German commanders and officials in Belgrade, interviewed a number of possible candidates to lead the new puppet government, then selected former Yugoslav Minister of the Army and Navy General Milan Nedić as the best available. The Germans had to apply significant pressure to Nedić to encourage him to accept the position, including threats to bring Bulgarian and Hungarian troops into the occupied territory and to send him to Germany as a prisoner of war.[93] Unlike most Yugoslav generals, Nedić had not been interned in Germany after the capitulation, but instead had been placed under house arrest in Belgrade.[83]

On 27 August 1941, about seventy-five prominent Serbs convened a meeting in Belgrade where they resolved that Nedić should form a Government of National Salvation (Serbian Cyrillic: Влада Националног Спаса, Serbian: Vlada Nacionalnog Spasa) to replace the Commissioner Government,[94] and on the same day, Nedić wrote to Danckelmann agreeing to become the Prime Minister of the new government on the basis of five conditions and some additional concessions. Two days later, the German authorities appointed Nedić and his government,[94] although real power continued to reside with the German occupiers.[95] There is no written record of whether Danckelmann accepted Nedić's conditions, but he did make some of the requested concessions, including allowing the use of Serbian national and state emblems by the Nedić government.[96] The Council of Ministers comprised Nedić, Aćimović, Janković, Ognjen Kuzmanović, Josif Kostić, Panta Draškić, Ljubiša Mikić, Čedomir Marjanović, Miloš Radosavljević, Mihailo Olćan, Miloš Trivunac, and Jovan Mijušković. The ministers fell into three broad groupings; those associated closely with Nedić, allies of Ljotić, and Aćimović. There was no foreign minister or minister for the Army and Navy.[97] The Nedić regime itself "had no status under international law, and no power beyond that delegated by the Germans",[98] and "was simply an auxiliary organ of the German occupation regime".[99]

The Nedić government was appointed at a time when the resistance was escalating quickly. On 31 August alone, there were 18 attacks on railway stations and railway lines across the territory.[87] On 31 August, the town of Loznica was captured by the Jadar Chetnik Detachment as part of a mutual co-operation agreement signed with the Partisans. List was surprised at the appointment of Nedić, as he had not been consulted. The fait accompli was accepted, although he held some reservations. On 1 September, he issued orders to Danckelmann and Bader for the suppression of the revolt, but did not share Danckelmann's optimism about Nedić's capacity to suppress the rebellion.[100]

The Nedić government ostensibly had a policy of keeping Serbia quiet to prevent Serbian blood from being spilled. The regime carried out German demands faithfully, aiming to secure place for Serbia in the New European Order created by the Nazis.[101] The propaganda used by the Nedić regime labeled Nedić as the "father of Serbia", who was rebuilding Serbia and who had accepted his role in order to save the nation.[102] Institutions that were formed by the Nedić government were similar to those in Nazi Germany, while documents signed by Milan Nedić used racist terminology that was taken from national-socialist ideology. The propaganda glorified the Serbian "race", accepting its "aryanhood", and determined what should be Serbian "living space". It urged the youth to follow Nedić in the building of the New Order in Serbia and Europe. Nedić aimed to assure the public that the war was over for Serbia in April 1941. He perceived his time as being "after the war", i.e., as a time of peace, progress and serenity. Nedić claimed that all deeds of his government were enabled by the occupants, to whom people should be grateful for secured life and "honorable place of associates in the building of the new World".[103]

Nedić hoped that his collaboration would save what was left of Serbia and avoid total destruction by German reprisals. He personally kept in contact with Yugoslavia's exiled King Peter, assuring the King that he was not another Pavelić (the leader of the Croatian Ustaše), and Nedić's defenders claimed he was like Philippe Pétain of Vichy France (who was claimed to have defended the French people while accepting the occupation), and denied that he was leading a weak Quisling regime.[104]

Crisis point

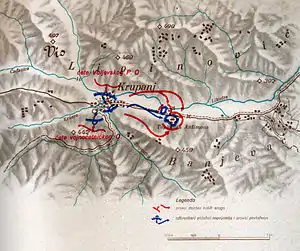

Soon after the appointment of the Nedić regime, the insurgency reached a crisis point. At the beginning of September, the area north of Valjevo, between the Drina and Sava rivers, was the centre of activity of well-armed and well-led insurgent groups. Six companies were committed against snipers that were targeting German troops and Serbian gendarmerie in the area. One of the companies was surrounded and cut-off at Koviljača, southwest of Loznica on the banks of the Drina, and had to be evacuated by air. But the German situation took a serious turn for the worse when the garrison of the antimony works at Krupanj were isolated on 1 September. Over the next day, the outlying posts of the 10th and 11th companies of the 704th Infantry Division's 724th Infantry Regiment were pushed into Krupanj by insurgent attacks. The rebels demanded that the garrison surrender, and when the deadline expired, launched a series of attacks on the main positions of both companies between 00:30 and 06:00 on 3 September. By that evening, both companies realized they were in danger of being overrun, and attempted to break out of the encirclement the following day. Of the 10th Company, only 36 men were able to make their way to Valjevo, and 42 men were missing from the 11th Company.[105] In total, despite air support, the two companies suffered nine dead, 30 wounded and 175 missing.[106]

On 4 September, List instructed Böhme to release the rest of the 433rd Infantry Regiment of the 164th Infantry Division to Bader. Ultimately, Böhme transferred the 125th Infantry Regiment and a battalion from the 220th Artillery Regiment instead. Bader had also taken control of the 220th Panzerjaeger (Anti-tank) Battalion from the 164th Infantry Division.[107] The following day, Danckelmann asked that if a front line division was not available to reinforce Bader's troops, that a division from the Replacement Army be provided.[108] In the following week, insurgents carried out 81 attacks on infrastructure, 175 on the Serbian gendarmerie, and 11 on German troops, who suffered another 30 dead, 15 wounded and 11 missing.[109] During that week, List advised OKW that the troops at hand, including those recently transferred from Böhme's command, would not suffice to put down the rebellion. He recommended that at least one powerful division be transferred to Serbia as soon as possible, along with tanks, armoured cars and armoured trains,[110] and asked that a single commander be appointed to direct all operations against the insurgents.[110]

By 9 September, with Danckelmann's approval, Nedić had recruited former Yugoslav Army soldiers into the gendarmerie, and increased its size from 2–3,000 to 5,000. He had also set up an auxiliary police force and a type of militia. Danckelmann had also provided Nedić with 15,000 rifles and a significant number of machine guns to equip his forces. On 15 September, Nedić used a radio address to demand that the insurgents lay down their arms and cease all acts of sabotage. He established special courts, and began a purge of the bureaucracy.[111] The lack of success achieved by this approach was evident when one battalion of gendarmes refused to fight the insurgents and another surrendered to them without firing a shot. When Bader objected to a dispersed deployment of the 125th Infantry Regiment, Danckelmann insisted it was necessary to send a battalion to Šabac to disarm the gendarmerie battalion there, who refused to fight. After the loss at Krupanj, the three occupation divisions were brought closer together and concentrated in greater strength, to reduce the threat of more companies being destroyed piecemeal. The 718th Infantry Division closed up on the west side of the Drina, the 704th near Valjevo, the 714th near Topola, and the 717th near the copper mines at Bor.[112] The dispersal of the 125th Infantry Regiment meant Bader was unable to mount a planned offensive against Valjevo. By this time, the Germans had no effective control of the area west of a line Mitrovica-Šabac-Valjevo-Užice.[113]

Reinforcements arrive

On 14 September, List's request for reinforcement was finally agreed by OKH. The 342nd Infantry Division was ordered to deploy from occupation duties in France,[114] and I Battalion of the 202nd Panzer Regiment of the 100th Panzer Brigade, equipped with captured French SOMUA S35 and Hotchkiss H35 tanks,[115] was also transferred to Bader's command.[114]

Mačva operation

The 342nd Infantry Division commenced its first major operation in late September in the Mačva region west of Šabac between the Drina and Sava. The targeted area was approximately 600 square kilometres (230 sq mi) in size. The first phase of the operation was the clearance of Šabac from 24–27 September, for which the division was reinforced by II/750th Infantry Regiment of the 718th Infantry Division, and by a company of the 64th Reserve Police Battalion. The second phase involved clearing of the wider area from 28 September – 9 October, supported by air reconnaissance, with limited dive-bomber support also available.[116]

Mount Cer operation

The Mačva operation was followed immediately by an operation aimed at clearing the insurgents from the Mount Cer area. From 10–15 October, the 342nd Infantry Division conducted a more targeted operation around Mount Cer, where the insurgents targeted in the Mačva operation had withdrawn. During this operation, the division was further reinforced with most of the captured French tanks of I/202nd Panzer Regiment.[117]

Jadar operation

After a few days break, on 19 and 20 October the 342nd Infantry Division conducted its third major operation, aimed at clearing the Jadar region and the main centre of insurgent activity in that area, Krupanj. It retained the support of two Panzer companies, and had fire support available from Hungarian patrol boats from their Danube Flotilla.[118]

Conflicts with the resistance

By late 1941, with each attack by Chetniks and Partisans, brought more reprisal massacres being committed by the German armed forces against Serbs. The largest Chetnik opposition group led by Mihailović decided that it was in the best interests of Serbs to temporarily shut down operations against the Germans until decisively beating the German armed forces looked possible. Mihailović justified this by saying "When it is all over and, with God's help, I was preserved to continue the struggle, I resolved that I would never again bring such misery on the country unless it could result in total liberation".[119] Mihailović then reluctantly decided to allow some Chetniks to join Nedić's regime to launch attacks against Tito's Partisans.[120] Mihailović saw as the main threat to Chetniks and, in his view, Serbs, as the Partisans[121] who refused to back down fighting, which would almost certainly result in more German reprisal massacres of Serbs. With arms provided by the Germans, those Chetniks who joined Nedić's collaborationist armed forces, so they could pursue their civil war against the Partisans without fear of attack by the Germans, whom they intended to later turn against. This resulted in an increase of recruits to the regime's armed forces.[120]

1942

In December 1941 and early January 1942 Chetnik leaders from Eastern Bosnia including Jezdimir Dangić in alliance with the government of Milan Nedić and the German military leadership in Belgrade negotiated about secession of 17 districts of eastern Bosnia and their annexation to Nedić's Serbia. During this negotiations was formed temporary Chetnik administration in eastern Bosnia with intention of establishing autonomy while the area does not united with Serbia. At that time it seems that the Chetnik movement had succeeded in creating initial basis for "Greater Serbia" but with diplomatic activity of the NDH authorities toward Berlin attempt to change state borders of the NDH were prevented. [122]

1943

In January 1943, Nedić proposed a basic law for Serbia, in effect a constitution creating an authoritarian corporative state similar to that long advocated by Dimitrije Ljotić and his pre-war fascist Yugoslav National Movement. Bader asked the various agency heads for their views, and despite some specialists recommending its adoption, Meyszner strongly opposed it, seeing it as a threat to German interests. Passed to Löhr then to Hitler, a response was received in March. Hitler considered it "untimely".[123] Nedić during negotiations with Hitler and Hermann Neubacher was arming and organising Bosnian Chetnik bands with attempt to expand his influence into East Bosnia.[124] One of Mihailović's closest personal friends and collaborators, Pavle Đurišić, simultaneously held a command for Nedić, and in 1943 tried to exterminate the Muslims and pro-Partisans of the Sandžak region.[121] The massacres he carried out were compared to the Croatian Ustashe and Muslim massacres of Serbs in the NDH in 1941.[121] Nedić was received by Hitler and German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop at Hitler's Wolf's Lair on 18 September 1943,[125] where Nedić requested the annexation of East Bosnia, Montenegro, the Sanjak, Kosovo-Metohija and Srem but this was rejected.[126] The Germans soon found mass executions of Serbs to be ineffectual and counterproductive, as they tended to drive the population into the arms of insurgents. The massacres caused Nedić to urge that the arbitrary shooting of Serbs be stopped, Böhme agreed and ordered a halt to the executions until further notice.[127] The ratio of 100 executions for one soldier killed and 50 executions for one soldier wounded was reduced by half in February 1943, and removed altogether later in the year.

1944

The first six months of 1944 were marked by heavy fighting in western and southern parts of the country, as the Yugoslav Partisans made several incursions across the Drina and Lim Rivers. These were made in order to augment the local detachments with veteran forces from Bosnia and Montenegro, defeat the Chetniks, and strengthen the NOVJ positions in anticipation of the arrival of the Soviet forces from the east.[128]

Collapse

By the fall of 1944, the Eastern Front had nearly reached the territory. Most of Serbia was liberated from the Germans over the course of the Belgrade Offensive carried out by the Red Army, Yugoslav Partisans and Bulgarian forces. With the onset of the Belgrade Offensive by the Red Army and the Partisans, the administration was evacuated from Serbia to Vienna in October 1944.[125]

The puppet governments established by the Germans were little more than subsidiary organs of the German occupation authorities, looking after some of the administration of the territory and sharing the blame for the brutal rule of the Germans. They had no international standing, even within the Axis. Their powers, quite limited from the beginning, were further reduced over time, which was frustrating and difficult for Nedić in particular.[95] Despite the ambitions of the Nedić government to establish an independent state, the area remained subordinated to the German military authorities until the end of its existence.[129][130]

The real power rested with the administration's Military Commanders, who controlled both the German armed forces and Serb collaborationist forces. In 1941, the administration's Military Commander, Franz Böhme, responded to guerrilla attacks on German forces by carrying out the German policy towards partisans that 100 people would be killed for each German killed and 50 people killed for each wounded German. The first set of reprisals were the massacres in Kragujevac and in Kraljevo by the Wehrmacht. These proved to be counterproductive to the German forces in the aftermath, as it ruined any possibility of gaining any substantial numbers of Serbs to support the collaborationist regime of Nedić. Additionally, it was discovered that in Kraljevo, a Serbian workforce group which was building airplanes for the Axis forces had been among the victims. The massacres caused Nedić to urge that the arbitrary shooting of Serbs be stopped, Böhme agreed and ordered a halt to the executions until further notice.[127]

Geography

Rump Serbia

On the day that the Axis invaded Yugoslavia, Hitler issued instructions for the dismemberment of the country, entitled the "Temporary Guidelines for Division of Yugoslavia". These instructions directed that what Hitler considered to be Alt Serbien (Old Serbia, meaning the territory of the Kingdom of Serbia prior to the Balkan Wars), would be placed under German occupation. This decision reflected the anger Hitler felt against Serbs, who he saw as the main instigators of the Belgrade military coup of 27 March 1941 which brought down the Yugoslav government that had acceded to the Tripartite Pact two days earlier. The general approach Hitler took in these instructions was to ensure that Serbia was punished by being reduced to a "rump".[131]

Banat

After discussions with both the Romanian and Hungarian governments, Hitler decided that the Vojvodina region would be divided by the river Tisa, with the eastern portion (the Serbian Banat) being placed under German occupation along with "Old Serbia". The portion of Vojvodina west of the Tisa was occupied and soon annexed by the Hungarians. Romanian-Hungarian rivalry was not the only reason for retaining the Banat under German occupation, as it also contained some 120,000 ethnic Germans (or Volksdeutsche) and was a valuable economic region. In addition to the Tisa, the other borders of the Banat were the Danube to the south, and the post-World War I Yugoslav-Romanian and Yugoslav-Hungarian borders in the north and east.[132]

Syrmia

An area of eastern Syrmia was initially included in the occupied territory for military and economic reasons, especially given Belgrade's airport and radio station were located there. The number of Volksdeutsche living in the area along with its role in providing food for Belgrade were also factors in the original decision. During this early period the border between the occupied territory and the NDH ran between the villages of Slankamen on the Danube and Boljevci on the Sava. However, after pressure from the NDH supported by the German ambassador to Zagreb, Siegfried Kasche it was gradually transferred to NDH control with the approval of the Military Commander in Serbia,[133] and became a formal part of the NDH on 10 October 1941,[134] forming the Zemun and Stara Pazova districts of the Vuka County of the NDH. The local Volksdeutsche soon asked for the area to be returned to German control, but this did not occur. As a result of the transfer of this region, the borders of the NDH then reached to the outskirts of Belgrade.[133]

Western border

Much of the western border between the occupied territory and the NDH had been approved by the Germans and announced by Ante Pavelić on 7 June 1941. However, this approved border only followed the Drina downstream as far as Bajina Bašta, and beyond this point the border had not been finalized. On 5 July 1941 this border was fixed as continuing to follow the Drina until the confluence with the Brusnica tributary east of the village of Zemlica, then east of the Drina following the pre-World War I Bosnia and Herzegovina–Serbia border.[135]

Sandžak

The Sandžak region was initially divided between the Germans in the north and the Italians in the south using an extension of the so-called "Vienna Line" which divided Yugoslavia into German and Italian zones of influence. The border of the occupied territory through the Sandžak was modified several times in quick succession during April and May 1941, eventually settling on the general line of Priboj–Nova Varoš–Sjenica–Novi Pazar, although the towns of Rudo, Priboj, Nova Varoš, Sjenica and Duga Poljana were on the Italian-occupied Montenegrin side of the border.[136] The town of Novi Pazar remained in German hands.[137] The NDH government was unhappy with these arrangements, as they wanted to annex the Sandžak to the NDH and considered it would be easier for them to achieve this if the Germans occupied a larger portion of the region.[136]

Kosovo

The line between the German occupation territory and Italian Albania in the Kosovo region was the cause of a significant clash of interests, mainly due to the important lead and zinc mines at Trepča and the key railway line Kosovska Mitrovica–Pristina–Uroševac–Kačanik–Skopje. Ultimately the Germans prevailed, with the "Vienna Line" extending from Novi Pazar in the Sandžak through Kosovska Mitrovica and Pristina, along the railway between Pristina and Uroševac and then towards Tetovo in modern-day North Macedonia before turning northeast to meet Bulgarian-annexed territory near Orlova Čuka. The Kosovska Mitrovica, Vučitrn and Lab districts, along with part of the Gračanica district were all part of the German-occupied territory. This territory included a number of other important mines, including the lead mine at Belo Brdo, an asbestos mine near Jagnjenica and a magnesite mine at Dubovac near Vučitrn.[138]

Administration

The territory of Serbia was the only area of Yugoslavia in which the Germans imposed a military government of occupation, largely due to the key transport routes and important resources located in the territory. Despite prior agreement with the Italians that they would establish an 'independent Serbia', Serbia in fact had a puppet government, Germany accorded it no status in international law except that of a fully occupied country, and it did not enjoy formal diplomatic status with the Axis powers and their satellites as the NDH did.[53] The occupation arrangements underwent a series of changes between April 1941 and 1944, however throughout the German occupation, the military commander in Serbia was the head of the occupation regime. This position underwent a number of title changes during the occupation. The day-to-day administration of the occupation was conducted by the chief of the military administration branch responsible to the military commander in Serbia. The puppet governments established by the Germans were responsible to the chief of military administration, although multiple and often parallel chains of German command and control meant that the puppet government was responsible to different German functionaries for different aspects of the occupation regime, such as the special plenipotentiary for economic affairs and the Higher SS and Police Leader.[139] For example, the plenipotentiary for economic affairs, Franz Neuhausen, who was Göring's personal representative in the occupied territory, was directly responsible to the Reichsmarshall for aspects of the German Four Year Plan, and had complete control over the Serbian economy.[140]

The territory was administered on a day-to-day basis by the Military Administration in Serbia (German: Militärverwaltung in Serbien). With the economic branch, the Military Administration initially formed one of the two staff branches responsible to the Military Commander in Serbia. In January 1942, with the appointment of a Higher SS and Police Leader in Serbia, a police branch was added. Whilst the heads of the economic and police branches of the staff were theoretically responsible to the Military Commander in Serbia, in practice they were responsible directly to their respective chiefs in Berlin. This created significant rivalry and confusion between the staff branches, but also created overwhelming difficulties for the Nedić puppet government that was responsible to the chief of military administration, who himself had little control or influence with the chiefs of the other staff branches.[141]

The officers serving as military commander of the territory were as follows:

| No. | Portrait | Name (Born-Died) |

Took office | Left office | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Military Commander in Serbia | |||||

| 1 | General der Flieger Helmuth Förster (1889–1965) | 20 April 1941 | 9 June 1941 | 50 days | |

| 2 | General der Flakartillerie Ludwig von Schröder (1884–1941) | 9 June 1941 | 18 July 1941 | 39 days | |

| 3 | General der Flieger Heinrich Danckelmann (1889–1947) | 27 July 1941 | 19 September 1941 | 54 days | |

| Plenipotentiary Commanding General in Serbia | |||||

| 4 | General der Gebirgstruppe Franz Böhme (1885–1947) | 19 September 1941 | 6 December 1941 | 78 days | |

| 5 | General der Artillerie Paul Bader (1883–1971) | 6 December 1941 | 2 February 1942 | 58 days | |

| Commanding General and Military Commander in Serbia | |||||

| 5 | General der Artillerie Paul Bader (1883–1971) | 2 February 1942 | 26 August 1943 | 1 year, 205 days | |

| Commander, Southeast Europe | |||||

| 6 | General der Infanterie Hans Felber (1889–1962) | 26 August 1943 | 20 October 1944 | 1 year, 55 days | |

Administrative divisions

The Germans created four military area commands (German: Feldkommandanturen) within the occupied territory, with each area command further divided into one or more district commands (German: Kreiskommandanturen), and about one hundred towns and localities had town or post commands (German: Platzkommandanturen or Ortskommandanturen) that were under the control of the district commands. Each area or district command had its own military, administrative, economic, police and other staff depending on local requirements, which allowed the chief of the Military Administration to implement German decrees and policies throughout the occupied territory. In December 1941, the military administration areas were adjusted to conform to corresponding civil areas. [141]

In the Banat, an area command (No. 610) was initially established at Pančevo, with a district command (No. 823) at Veliki Bečkerek. The Pančevo area command was subsequently moved to Kraljevo, but the district command at Veliki Bečkerek remained in place, becoming an independent district command reporting directly to the Military Commander.[63]

From December 1941 until the German withdrawal, the German area commands were located in Belgrade, Niš, Šabac and Kraljevo, with district commands as follows:[53]

- Area Command No. 599 Belgrade: District Command No. 378 in Požarevac.

- Area Command No. 809 Niš: District Commands No. 857 in Zaječar and No. 867 in Leskovac.

- Area Command No. 816 Šabac: District Command No. 861 in Valjevo.

- Area Command No. 610 Kraljevo: District Commands No. 832 in Kragujevac, No. 833 in Kruševac, No. 834 in Ćuprija, No. 838 in Kosovska Mitrovica, and No. 847 in Užice.

The German area and district commanders directed and supervised the corresponding representative of the Serbian puppet government.[142]

The puppet government established okruzi and srezovi with the former having identical boundaries with the military districts.

Administration of the Banat

Administration of northern Kosovo

Military

Axis occupation forces

Due to the serious nature of the uprising that started in July 1941, the Germans began sending combat troops back to the territory, starting in September with the 125th Infantry Regiment supported by additional artillery deployed from Greece, and by the end of the month the 342nd Infantry Division began arriving from occupied France. A detachment of the 100th Tank Brigade was also sent to the territory. These troops were used against the resistance in the north-west of the territory, which they pacified by the end of October. Due to stronger resistance in the south-west, the 113th Infantry Division arrived from the Eastern Front in November and this part of the territory was also pacified by early December 1941.[143]

Following the suppression of the uprising, the Germans again withdrew the combat formations from the territory, leaving behind only the weaker garrison divisions. In January 1942, the 113th Infantry Division returned to the Eastern Front, and the 342nd Infantry Division deployed to the NDH to fight the Partisans. To secure the railroads, highways and other infrastructure, the Germans began to make use of Bulgarian occupation troops in large areas of the occupied territory, although these troops were under German command and control. This occurred in three phases, with the Bulgarian 1st Occupation Corps consisting of three divisions moving into the occupied territory on 31 December 1941. This corps was initially responsible for about 40% of the territory (excluding the Banat), bounded by the Ibar river in the west between Kosovska Mitrovica and Kraljevo, the West Morava river between Kraljevo and Čačak, and then a line running roughly east from Čačak through Kragujevac to the border with Bulgaria. They were therefore responsible for large sections of the Belgrade–Niš–Sofia and Niš–Skopje railway lines, as well as the main Belgrade–Niš–Skopje highway.[144]

In January 1943, the Bulgarian area was expanded westwards to include all areas west of the Ibar river and south of a line running roughly west from Čačak to the border with occupied Montenegro and the NDH.[145] This released the 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division Prinz Eugen, which had been garrisoning this area over the winter, to deploy into the NDH and take part in Case White against the Partisans. Many members of the Volksdeutsche from Serbia and the Banat were serving in the 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division Prinz Eugen.[146] This division was responsible for war crimes committed against the peoples of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[147]

In July 1943, the Bulgarian occupation zone expanded northwards, with a fourth division, the 25th Division taking over from the 297th Infantry Division in the rest of the territory (excluding the Banat) that did not share a border with the NDH. From this point, German forces only directly occupied the immediate area of Belgrade, the northwest region of the territory that shared a border with the NDH, and the Banat.[145]

Collaborationist forces

Aside from the Wehrmacht, which was the dominant Axis military in the territory, and (from January 1942) the Bulgarian armed forces, the Germans relied on local collaborationist formations for the maintenance of order.[148]Local movements were formed nominally as subordinate to the local puppet government, but remained under direct German control throughout the war. The primary collaborationist formation was the Serbian State Guard, which functioned as the "regular army" of the Government of National Salvation of General Nedić (hence their nickname, Nedićevci). By October 1941 German-equipped Serbian forces had, under supervision, become increasingly effective against the resistance.[149]

In addition to the Serbian State Guard regulars, there were three officially organized German auxiliary armed groups formed during the German occupation. These were the Serbian Volunteer Corps, the Russian Corps, and the small Auxiliary Police Troop composed of Russian Volksdeutsche. The Germans also used two other armed groups as auxiliaries, the Chetnik detachments of Kosta Pećanac which started collaborating with the Germans from the time of the Nedić government's appointment in August 1941, and later the 'legalized' Chetnik detachments of Mihailović.[150] Some of these organizations wore the uniform of the Royal Yugoslav Army as well as helmets and uniforms purchased from Italy, while others used uniforms and equipment from Germany.[151]

Foremost among these was the Serbian Volunteer Corps, largely composed of paramilitaries and supporters of the fascist Yugoslav National Movement (ZBOR) of Ljotić (hence the nickname Ljotićevci). Founded in 1941, the formation was initially called "Serbian Volunteer Command", but was reorganized in 1943 and renamed the "Serbian Volunteer Corps", with Kosta Mušicki as the operational leader.[152] At the end of 1944, the Corps and its German liaison staff were transferred to the Waffen-SS as the Serbian SS Corps and comprised a staff from four regiments each with three battalions and a training battalion. The Russian Corps was founded on 12 September 1941 by white Russian emigres, and remained active in Serbia until 1944.

Recruits to the collaborationist forces increased in numbers following joining of Chetnik groups loyal to Pećanac. By their own postwar account, these Chetniks joined with the intention to destroy Tito's Partisans, rather than supporting Nedić and the German occupation forces, whom they later intended to turn against.[120]

In late 1941, the main Chetnik movement of Mihailović ("Yugoslav Army in the Fatherland") was increasingly coming to an understanding with Nedić's government. After being dispersed following conflicts with Partisan and German forces during the First Enemy Offensive, Chetnik troops in the area came to an understanding with Nedić. As "legalized" Chetnik formations, they collaborated with the quisling regime in Belgrade, while nominally remaining part of the Mihailović Chetniks.[153] As military conditions in Serbia deteriorated, Nedić increasingly cooperated with Chetnik leader Draža Mihailović. Over the course of 1944 Chetniks assassinated two high-ranking Serbian military officials who had obstructed their work. Brigadier-general Miloš Masalović was murdered in March, while rival Chetnik leader Pećanac was killed in June.[154]

Police

At the beginning of the occupation, the Military Commander in Serbia was provided with a Security Police Special Employment Squad (German: Sicherheitspolizei Einsatzgruppen) consisting of detachments of Gestapo, criminal police and the SD or Security Service (German: Sicherheitsdienst). Initially commanded by SS and Police Leader (German: SS und Polizeiführer) Standartenführer und Oberst der Polizei Wilhelm Fuchs, this group was technically under the control of the chief of the Military Administration in Serbia, Harald Turner, but in practice reported direct to Berlin. In January 1942, the status of the police organisation was raised by the appointment of a Higher SS and Police Leader (German: Höhere SS und Polizeiführer) Obergruppenführer und Generalleutnant der SS August Meyszner. Meyszner was replaced in April 1944 by Generalleutnant der SS Hermann Behrends.[155]

Demographics

The population of the occupied territory was approximately 3,810,000,[156] composed primarily of Serbs (up to 3,000,000) and Germans (around 500,000). Other nationalities of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia have been mostly separated from Serbia and included within their respective ethnic states – e.g., the Croats, Bulgarians, Albanians, Hungarians, etc. Most of the Serbs however ended up outside the Nazi Serbian state, as they were forced to join other states.

By the summer of 1942, is estimated that around 400,000 Serbs had been expelled or had fled from others parts of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and were living in the occupied territory.[156]

The autonomous area of the Banat was a multi-ethnic area with a total population of 640,000, of which 280,000 (43.7%) were Serbs, 130,000 (20.3%) were Germans, 90,000 (14.0%) were Hungarians, 65,000 (10.1%) Romanians, 15,000 (2.3%) Slovaks and 60,000 (9.3%) of other ethnicities.[63]

Of the 16,700 Jewish people in Serbia and the Banat, 15,000 (89.8%) were killed. In total, it is estimated that approximately 80,000 people were killed from 1941 to 1944 in concentration camps the occupied territory.[157] Turner declared in August 1942, that the "Jewish question" in Serbia had been "liquidated" and that Serbia was the first country in Europe to be Judenfrei; free of Jews.[14]

Economy

Banking and currency

After the collapse of Yugoslavia, the National Bank of Yugoslavia was forced into liquidation on 29 May 1941, and two days later a decree was issued by the Military Commander in Serbia creating the Serbian National Bank. The new bank was under the direct control of Franz Neuhausen, the plenipotentiary general for economic affairs, who appointed the governor and board members of the bank, as well as a German commissioner who represented Neuhausen at the bank and had to approve all important transactions. The new bank introduced the Serbian dinar as the only legal currency and called in all Yugoslav dinars for exchange.[44][158]

The traditional Obrenović coat of arms was found on bills and coins minus the royal crown.

After the war Yugoslavia scrapped the Serbian dinar and other currencies of the Independent State of Croatia and Montenegro in 1945.[159]

German exploitation of the economy

Immediately after the capitulation of Yugoslavia, the Germans confiscated all the assets of the defeated Yugoslav army, including about 2 billion dinars in the occupied territory of Serbia. It also seized all usable raw materials and used occupation currency to purchase goods available in the territory. It then placed under its control all useful military production assets in the country, and although it operated some armament, ammunition and aircraft production factories in situ for a short period of time, after the July 1941 uprising, it dismantled all of them and relocated them outside the territory.[160]

Next, the occupation authorities assumed control of all transportation and communication systems, including riverine transport on the Danube. And finally, it took control of all significant mining, industrial and financial enterprises in the territory that were not already under Axis control prior to the invasion.[161]

In order to coordinate and ensure maximum exploitation of the Serbian economy, the Germans appointed Franz Neuhausen, who was effectively the economic dictator in the territory. Initially the Plenipotentiary General for Economic Affairs in Serbia, he soon became the Plenipotentiary for the Four Year Plan under Göring, Plenipotentiary for Metal Ores Production in South-East Europe, and Plenipotentiary for Labour in Serbia. From October 1943, he became the Chief of Military Administration in Serbia, responsible for the administration of all aspects of the entire territory. Ultimately, he had full control of the Serbian economy and finances, and fully controlled the Serbian National Bank, in order to use all parts of the Serbian economy to support the German war effort.[162]

As part of this, the Germans imposed huge occupation costs on the Serbian territory from the outset, including amounts required to run the military administration of the territory as determined by the Wehrmacht, and an additional annual contribution to the Reich set by the Military Economic and Armaments Office. The occupation costs were paid by the Serbian Ministry of Finance on a monthly basis into a special account with the Serbian National Bank.[163]

Over the entire period of the occupation, the Serbian puppet governments paid the Germans about 33,248 million dinars in occupation costs. Occupation costs amounted to about 40% of the current national income of the territory by mid-1944.[164]

Culture

With the dissolution of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, many newspapers went out of print while new papers were formed. Soon after the occupation began, the German occupation authorities issued orders requiring the registration of all printing equipment and restrictions on what could be published. Only those that had been registered and approved by the German authorities could edit such publications.[44] On 16 May 1941 the first new daily, Novo vreme (New Times), was formed. The weekly Naša borba (Our Struggle) was formed by the fascist ZBOR party in 1941, its title echoing Hitler's Mein Kampf (My Struggle). The regime itself released the Službene novine (Official Gazette) which attempted to continue the tradition of the official paper of the same name which was released in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.[165]

The state of film in Serbia was somewhat improved compared to the situation in the Yugoslavia. During that time, the number of cinemas in Belgrade was increased to 21, with a daily attendance of between 12,000 and 15,000 people.[166] The two most popular films were 1943's Nevinost bez zaštite and Golden City which were watched by 62,000 and 108,000 respectively.[167]

The German occupation authorities issued special orders regulating the opening of theatres and other places of entertainment which excluded Jews.[44] The Serbian National Theatre in Belgrade remained open during this time. Works performed during this period included La bohème, The Marriage of Figaro, Der Freischütz, Tosca, Dva cvancika and Nesuđeni zetovi.

Racial persecution

Racial laws were introduced in all occupied territories with immediate effects on Jews and Roma people, as well as causing the imprisonment of those opposed to Nazism. Several concentration camps were formed in Serbia and at the 1942 Anti-Freemason Exhibition in Belgrade the city was pronounced to be free of Jews (Judenfrei). On 1 April 1942, a Serbian Gestapo was formed. An estimated 120,000 people were interned in Nazi-run concentration camps in the occupied territory between 1941 and 1944. 50,000[168] to 80,000 were killed during this period.[157] The Banjica Concentration Camp was jointly run by the German Army and Nedic's regime.[6] Serbia became the second country in Europe, following Estonia,[169][170] to be proclaimed Judenfrei (free of Jews).[14][171][172][173][174] Approximately 14,500 Serbian Jews – 90 percent of Serbia's Jewish population of 16,000 – were murdered in World War II.[175]

Collaborationist armed formations forces were involved, either directly or indirectly, in the mass killings of Jews, Roma and those Serbs who sided with any anti-German resistance or were suspects of being a member of such.[176] These forces were also responsible for the killings of many Croats and Muslims;[177] however, some Croats who took refuge in the occupied territory were not discriminated against.[178] After the war, the Serbian involvement in many of these events and the issue of Serbian collaboration were subject to historical revisionism by Serbian leaders.[179][180]

The following were the concentration camps established in the occupied territory:

- Banjica concentration camp (Belgrade)

- Crveni krst concentration camp (Niš)

- Topovske Šupe (Belgrade)

- Šabac concentration camp

Located on the outskirts of Belgrade, Sajmište concentration camp was actually situated on the territory of the Independent State of Croatia.

Post-war trials