A military commissariat (from Russian: военный комиссариат, shortened as военкомат, voyenkomat), is an institution that is part of military service or law enforcement mechanisms in some European countries. As part of the British Army in the 19th century, military commissariats were used for organisational, accounting and bookkeeping duties regarding military transport, personnel and equipment. The most widespread historic use of military commissariats existed as part of administrative military infrastructure in the Soviet Union. Each Soviet district would have a military commissariat that was responsible for keeping documentation up to date concerning military resources, including the labour force, in their region. Military commissariats in the Soviet Union were also tasked with the recruitment and training of military servicemen. The use of military commissariats as local military administrative agencies continued as a part of modern Russia after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. There has been criticism and speculation regarding corruption in the recruitment process of military personnel and allegations of an abusive military culture in commissariats since their inception. This has caused the role of military commissariats as administrative agencies to be questioned. Buildings that were military commissariats still serve their purpose in Russia and some other post-Soviet states. In France and Italy, the word "commissariat" can refer to factions of the police and law enforcement, some of whom are connected to the military.

In Soviet Russia / Soviet Union

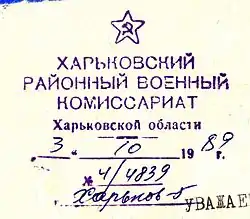

A military commissariat (Russian: Bоенный коммисариат, translit: voyenny kommisariat) was a local military administrative agency used in the Soviet Union to provide administrative and organisational military services. They were led by a military commissar (Russian: Bоенный коммисар, translit: voyenny kommisar) who worked in a political and bureaucratic role alongside a regional military commander who served as a traditional military official.[1] As is typical of Soviet phraseology, military commissariats can be referred to in Russian as 'voyenkomat' and military commissars can be referred to as 'voyenkom'; examples of Soviet portmanteaus.[2] Military commissariats were used in Soviet Russia and later Soviet Union from 1917 until the dissolution in 1991.[3] Soviet republics were divided into Krais and Oblasts and then into national districts and at each division a military commissariat was instated.[3] The role of the military commissariat at each stage of hierarchy differed; however, its core functions centred around administrative housekeeping regarding military personnel and military equipment and the provision of military training.[3] Other duties included troop mobilisation, forced conscription and punishments for draft dodging, preparing local men for service, registering all relevant weaponry including all machinery and cars in the region, delivering pensions to retired army personnel, and selecting and promoting officers.[3]

The structure and function of military commissariats initially developed between 1917 and 1922 during the Russian Civil War. A political officer was introduced by the Red Army to each occupied military district to collaborate with the existing military commander and to provide military administrative services.[4] This officer was the precursor to the military commissar.[1] The introduction of a political officer alongside a military commander at a local level established leadership accountability and cooperation in each Soviet district and also lay foundation for a close relationship to develop between the political and military spheres in the Soviet Union.[5] Additionally, strong relations between political and military figures allowed for an overarching administrative structure to interact with civilians through a combined political and military partnership.[1] The military commissariat system rose in importance during the 1920s and 1930s as it allowed the Communist Party of the Soviet Union to exert political control alongside the military at a local level.[3] Vladimir Lenin, head of government of Soviet Russia and subsequent Soviet Union from 1917 to 1924, said that "without military commissariats we would not have a Red Army".[3]

Military commissariats organised the mobilisation of troops before the Soviet invasions of Finland, Poland and other countries in 1939 and in the subsequent outbreak of World War II.[4] As part of recruitment processes and to encourage military service and participation in World War II military commissariats would organise dispatch centres in their individual districts that displayed various propaganda materials such as portraits of Soviet leaders and slogans that encouraged defence of the homeland.[4] Additionally, military commissariats would organise local military functions, military discussions, artistic performances and film screenings to increase morale and to promote military service.[4]

After 1945, military commissariats and their administrative processes were increasingly monitored closely by the United States through espionage to establish greater understanding of the Soviet Armed Forces.[6] This is a result of the bookkeeping and accounting information held by individual military commissariats regarding population, recruitment and equipment numbers in their districts.

In the 20th century the Soviet Union was considered a major military strength.[7] The Soviet Armed Forces were a source of pride for the state and this is reflected in the Soviet Union's military budget which was the largest in the world at the time measured as a percentage of Gross National Product, reaching 25% of the country's total Gross Domestic Product.[7] This military culture and expenditure is reflected in the development of the military commissariat system which allowed the military to grow and serve as an important feature of all Soviet districts.

Current use

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Russian military and political spheres expected the newly founded Commonwealth of Independent States to develop and continue their combined military forces.[5] But some CIS states decided to form independent security and military policies.[5] This left Soviet military infrastructure such as military commissariats to stay unused in these post-Soviet states. In the newly founded Russian Federation, military reform began under the presidency of Boris Yeltsin. Yury Skokov, then Secretary of the Security Council, began drafting a National Security Concept in 1992.[5] The document was not signed by Yeltsin until 1997 and this is attributed to consecutive debates and discussions surrounding its content, and the various internal and external instability experienced by Russia during the 1990s.[5] Alongside decreases in military expenditure throughout this time period, this stagnated progression of military reform in the transition between the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation. Military commissariats support military services and depend on military spending.[8]

In Russia

Military commissariats fulfil the same roles in Russia as they did in the Soviet Union and continue to operate in their individual districts. They recruit servicemen to the Russian Army and choose who is eligible and ineligible for service.[9] Konstantin Preobrazhensky, a former KGB colonel and intelligence expert, has suggested that military commissariats in Russia enlist and report individuals to the FSB and the police as well as to the military, similarly to Soviet times.[10] Political and social debate regarding a transition to an all-volunteer professional military service model exists in Russia and in this context the purpose of the military commissariat is questioned. Most people who consider themselves Soviet patriots oppose the abolition of forced conscription.[9]

Since the decrease in military expenditure and regulation that occurred during the 1990s, military service programs and institutions such as military commissariats have faced accusations of corruption.[9][8][2] The quality of military service and training is also believed to have decreased.[7] Military commissars allegedly accept bribes to exempt individuals from compulsory military service and this method of avoiding conscription along with others such as attaining false medical certificates contribute to the common concern of draft evasion. This is seen as a continuation of Soviet traditions, when children of nomenklatura were exempt from military service.[9] Another contentious issue regarding military commissariats and military commissars in modern Russia is the continued use of Soviet portmanteaus and phraseology in the words 'voyenkom' (military commissar) and 'voyenkomat' (military commissariat). This has been regarded as a form of Soviet nostalgia.[8]

The military in Russia has become increasingly unpopular amongst Russian citizens, with a 2011 Levada Centre study finding that 54% of Russian parents would not want their son to join the army.[9] Additionally, the military has a legacy of hazing and brutality in the form of dedovshchina that stretches back to the 1920s.[8] This reputation negatively connotes back to the role of military commissariats in conscription, and its effect of increased draft evasion.[9] These concerns were illuminated by the creation and mainstream popularity of human rights organisations such as the Union of the Committees of Soldiers' Mothers of Russia, which seeks to expose the abuses experienced by men in the Russian military.[11] In 1998, human losses in the Russian army were over 15 000, with every fourth death being a suicide.[11] Anna Politkovskaya, a Russian journalist and activist, has provided anecdotal information regarding the concerns of many families in response to conscription and the ways men are drafted by military commissariats.[12] Volunteers from the committee also make routine visits to military commissariats to ensure procedures are correct and to oversee developments. This is accepted in military commissariats in the interests of continuing military reform and minimising corruption.[11]

In post-Soviet states

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, all former members organised and developed their own defence, security and military programs.[5] Since the annexation of Crimea in 2014 Russian foreign policy has focused on geopolitical competition similar to the foreign policy ideas of the Soviet Union. Military commissariats continue to operate in fringe and de facto states around the Russian border such as in South Ossetia and Abkhazia.[10] As a result of the information collected by individual military commissariats regarding the population in each district, their practice in disputed post-Soviet territories has been scrutinised by critics of the Russian government and their policies where it is seen as an example of continued Russian intervention in post-Soviet states.[10]

Other uses

In other European countries

The word commissariat, within the French Armed Forces and the Italian Armed Forces (and formerly in the British Army) designates services providing supplies, as well as financial and legal support to units, roughly equivalent to the Quartermasters in the US military. Officers from these services are called commissaires (in French), commissari (in Italian) and commissaries in English. Additionally the word 'commissariat' in France and French speaking countries and territories can be used as an equivalent to 'police station'.[13]

In Britain, military commissariats were used first in the Crimean War between 1853 and 1856.[14] They were created as a part of the Treasury and were responsible for transporting and rationing all food, fuel and provisions from Britain to dispatched troops in Crimea as well as organising and accounting for all relevant documentation regarding supply quantities and their destinations.[14] This system and its procedures were criticised by members of the British Army at the time of the Crimean War and has been criticised by military historians since for being inefficient as there were food shortages experienced by British soldiers during the Crimean War.[14] The food shortages are attributed to the military commissariat structures that required documentation to be provided by military commanders and their soldiers that in most cases was not properly provided in time.[14] This British system was inefficient in comparison with the equivalent French intendance militaire.[15] The chain of command was also criticised at the time as it was thought that the commissariats should respond to the War Department and not to the Treasury.[14] Commissariats were transferred to the authority of the War Department in December 1854.[15] This process represented a militarisation of what was the initially uniquely administrative commissariat system.[15] However, the guidelines and bureaucracy used by military commissariats during the Crimean War provided consistency and uniformity to the procedures during the war which Britain ultimately contributed to winning.[14]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Colton, T. J. 2003, Commissars, Commanders and Civilian Authority, Harvard University Press: Cambridge. ISBN 9780674497443.

- 1 2 Borshchevskaya, Anna (2020). "The Role of the Military in Russian Politics and Foreign Policy Over the Past 20 Years". Orbis. 64 (3): 434–446. doi:10.1016/j.orbis.2020.05.006. PMC 7329278. PMID 32834128.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Scott, H. F. & Scott, W. F. 1981, The Armed Forces of the USSR, Routledge: New York. ISBN 0891582762.

- 1 2 3 4 Rostov, Nikolai D.; Eremin, Igor A.; Kuznetsov, Sergei I. (2 January 2019). "The Particularities of Military Mobilization Campaigns in Siberia in the Summers of 1914 and 1941". The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 32 (1): 93–115. doi:10.1080/13518046.2019.1552704. S2CID 151291671.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Aldis, A. & McDermott, R. N. 2003, Russian Military Reform, 1992–2002, Frank Cass: London. ISBN 0-203-01105-8.

- ↑ Defence Intelligence Agency, 1982, Intelligence Appraisal USSR: Oblast Military Commissariat Activity, accessed 31 December 2023, via Central Intelligence Agency Electronic Reading Room.

- 1 2 3 Barany, Z. D. 2007, Democratic Breakdown and the decline of the Russian military, Princeton University Press: New Jersey. ISBN 9780691128962.

- 1 2 3 4 Spivak, Andrew L.; Pridemore, William Alex (2004). "Conscription and Reform in the Russian Army". Problems of Post-Communism. 51 (6): 33–43. doi:10.1080/10758216.2004.11052188. S2CID 62805983.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gresh, Jason P. (2011). "The Realities of Russian Military Conscription". The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 24 (2): 185–216. doi:10.1080/13518046.2011.572699. S2CID 154709663.

- 1 2 3 Preobrazhensky, K. 2009. South Ossetia: KGB Backyard in the Caucasus. The Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst. http://www.cacianalyst.org/publications/analytical-articles/item/11799-analytical-articles-caci-analyst-2009-3-11-art-11799.html

- 1 2 3 Cimbala, S. J. 2014, The Russian military into the twenty-first century, Routledge: London, ISBN 9781315038506.

- ↑ Politkovskaya, A. 2004, Putin's Russia. The Harvill Press: London.

- ↑ Méjean, Jean-Max (December 2010). "Commissariat". Jeune Cinéma (335): 64–65. ProQuest 1560536085.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Funnell, Warwick N. (1990). "Pathological responses to accounting controls: The British commissariat in the Crimea 18541856". Critical Perspectives on Accounting. 1 (4): 319–335. doi:10.1016/1045-2354(90)04031-9. S2CID 143607539.

- 1 2 3 Dawson, Anthony (13 May 2015). "The French Army and British Army Crimean War Reforms". 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century. 2015 (20). doi:10.16995/ntn.707.

.JPG.webp)