| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Estimates from 1.6 million to 2.5 million[1][2] Kurds make up between 5% and 10% of Syria's population.[3][4] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Northeastern Syria, Afrin, Kobani[5] | |

| Languages | |

| Mainly Kurdish (Kurmanji);[6] also Arabic (North Levantine Arabic, Modern Standard Arabic) | |

| Religion | |

| Majority Sunni Islam and Yazidism, also Shia Islam, Christianity[7] |

.jpg.webp)

The Kurdish population of Syria is the country's largest ethnic minority,[8] usually estimated at around 10% of the Syrian population[9][10][8][11][12][13] and 5% of the Kurdish population.

The majority of Syrian Kurds are originally Turkish Kurds who have crossed the border during different events in the 20th century.[14] There are three major centers for the Kurdish population in Syrian, the northern part of the Jazira, the central Euphrates Region around Kobanî and in the west the area around Afrin.[15] All of these are on the Syria-Turkey border, and there are also substantial Kurdish communities in Aleppo and Damascus further south.

Human rights organizations have accused the Syrian government of routinely discriminating and harassing Syrian Kurds.[16][17] Many Kurds seek political autonomy for what they regard as Western Kurdistan, similar to the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq, or to be part of an independent state of Kurdistan. In the context of the Syrian Civil War, Kurds established[18][19][20] the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria.[21]

Demographics

Syrian Kurds live mainly in three Kurdish pockets in northern Syria adjacent to Turkey.[5] Many Kurds also live in the large cities and metropolitan areas of the country, for example, in the neighborhood Rukn al-Din in Damascus, which was formerly known as Hayy al Akrad (Kurdish Quarter), and the Aleppo neighborhoods of al Ashrafiya[22] and Sheikh Maqsood.[23]

Kurds are the largest ethnic minority in Syria, and make up between 5 and 10 percent of the Syrian population.[24][12][2][10][1] The estimates are diluted due to the effects of the Syrian civil war and the permeability of the Syrian-Turkish border.[25] The Kurdish population in Syria is relatively small in comparison to the Kurdish populations in nearby countries, such as Turkey, Iran, and Iraq. The majority of Syrian Kurds speak Kurmanji, a Kurdish dialect spoken in Turkey and northeastern Iraq and Iran.[26]

It is estimated that at the beginning of the 20th century around 12,000 Kurds lived in Damascus; an unknown number of Kurds lived in the Kurd-Dagh region; 16,000 Kurds lived in the Jarabulus region; and an unknown number lived in the Jazira province, where they were likely the majority.[27] The extension of the railway and road to Nusaybin in 1918 intensified the immigration of Kurds southwards into the Syrian foothills and plains along rivers.[28] In the 1920s after the failed Kurdish rebellions in Kemalist Turkey, there was a large migration of Kurds to Syria's Jazira province. It is estimated that 25,000 Kurds fled at this time to Syria.[29] The French official reports show the existence of 45 Kurdish villages in Jazira prior to 1927. A new wave of refugees arrived in 1929.[30] The French authorities continued to allow Kurdish migration into the Mandate, and by 1939, the villages numbered between 700 and 800.[30] The French geographers Fevret and Gibert estimated that in 1953 out of the total 146,000 inhabitants of Jazira, agriculturalist Kurds made up 60,000 (41%), nomad Arabs 50,000 (34%), and a quarter of the population were Christians.[28]

Even though some Kurdish communities have a long history in Syria,[31] most Syrian Kurds originate from Turkey and have immigrated during the 20th century to escape the harsh repression of the Kurds in that country.[14] Kurds were later joined in Syria by a new large group that drifted out of Turkey throughout the interwar period during which the Turkish campaign to assimilate its Kurdish population was at it highest.[14] The government has used the fact that some Kurds fled to Syria during the 1920s to claim that Kurds are not indigenous to the country and to justify its discriminatory policies against them.[14]

History

Ayyubid period

In the 12th century, Kurdish and other Muslim regiments accompanied Saladin, who was a Kurd from Tikrit, on his conquest of the Middle East and establishment of the Ayyubid dynasty (1171–1341), which was administered from Damascus. The Kurdish regiments that accompanied Salidin established self-ruled areas in and around Damascus.[32] These settlements evolved into the Kurdish sections of Damascus of Hayy al-Akrad (the Kurdish quarter) and the Salhiyya districts located in the north-east of Damasacus on Mount Qasioun.[33]

Ottoman period

The Kurdish community's role in the military continued under the Ottomans. Kurdish soldiers and policeman from the city were tasked with both maintaining order and protecting the pilgrims’ route toward Mecca.[32] Many Kurds from Syria's rural hinterland joined the local Janissary corps in Damascus. Later, Kurdish migrants from diverse areas, such as Diyarbakir, Mosul and Kirkuk, also joined these military units which caused an expansion of the Kurdish community in the city.[30]

The Kurdish dynasty of Janbulads ruled the region of Aleppo as governors for the Ottomans from 1591 to 1607.[35] At the beginning of the 17th century, Kurdish tribes were forcefully settled in the vicinity of Jarabulus and Seruj by the Ottoman sultans.[36] In the mid-18th century, Ottomans recognized Milli tribal leaders as iskan başı or chief of sedentarization in Raqqa area. They were given taxing authority and controlling other tribes in the region. In 1758, Milli chief and iskan başı Mahmud bin Kalash entered Khabur valley, subjugated the local tribes and brought the area under control of Milli confederation and attempted to set up an independent principality. In 1800, the Ottoman government appointed the Milli chief Timur as governor of Raqqa (1800–1803).[37][38][39]

The Danish writer Carsten Niebuhr, who traveled to Jazira in 1764, recorded five nomadic Kurdish tribes (Dukurie, Kikie, Schechchanie, Mullie and Aschetie) and six Arab tribes (Tay, Kaab, Baggara, Geheish, Diabat and Sherabeh).[40] According to Niebuhr, the Kurdish tribes were settled near Mardin in Turkey, and paid the governor of that city for the right of grazing their herds in the Syrian Jazira.[41] These Kurdish tribes gradually settled in villages and cities and are still present in Jazira (modern Syria's Hasakah Governorate).[42]

In the mid 1800s, the Emirate of Bohtan of Bedir Khan Beg span over parts of present day northeastern Syria.[43] The demographics of this area underwent a huge shift in the early part of the 20th century. Ottoman authorities with the cooperation of Kurdish troops (and to a lesser degree, Circassian and Chechen tribes) persecuted Armenian and Assyrian Christians in Upper Mesopotamia and were granted their victims' land as a reward.[44][45] Kurds were responsible for most of the atrocities against Assyrians, and Kurdish expansion happened at the expense of Assyrians (due to factors like proximity).[46] Kurdish as well as Circassian and Chechen tribes cooperated with the Ottoman (Turkish) authorities in the massacres of Armenian and Assyrian Christians in Upper Mesopotamia, between 1914 and 1920, with further attacks on unarmed fleeing civilians conducted by local Arab militias.[47][48][45][49][50]

In other parts of the country during this period, Kurds became local chiefs and tax farmers in Akkar (Lebanon) and the Qusayr highlands between Antioch and Latakia in northwestern Syria. The Afrin Plateau northwest of Aleppo, just inside what is today Syria, was officially known as the "Sancak of the Kurds" in Ottoman documents.[51] The Millis revolted against the Ottoman government after the death of their leader Ibrahim Pasa and some of them eventually settled for the most part on the Syrian side of the newly drawn Turkish-Syrian border of 1922.[52][53]

When Maurice Abadie, a French general, was overseeing the French occupation of Syria, he made some observations on the settlements of Kurds in 1920:

Over the course of the past century the Kurds have migrated and spread throughout northern Syria.

Those who have spread to the west of the Euphrates have come from the valleys of Kurdistan. They have gradually settled in and live alongside the Turks, Turkmen, Christians and Arabs, all of whose customs they have adopted to some degree.[54]

Treaty of Sèvres and colonial borders

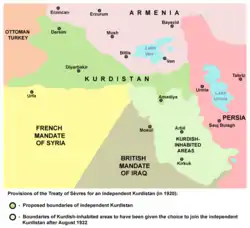

Following World War I, the victorious Allied powers and the defeated Ottoman Empire signed the Treaty of Sèvres of 10 August 1920. The treaty stipulated that Ottoman Kurdistan, which included Kurdish inhabited areas in southeastern Turkey and norther Iraq to be given autonomy within the new Turkish Republic, with the choice for full independence within a year. The Kemalist victory in Turkey and subsequent territorial gains during the Turkish War of Independence led to the renegotiated Treaty of Lausanne of 24 July 1923, which made no mention of a future Kurdish state. The majority of Ottoman Kurdish territory was given to Turkey and the rest in British Mandate of Iraq.[55] Two small pockets with Kurdish majority at the border with Turkey (Afrin and Ayn al-Arab) were included in the State of Aleppo who, in contrast to the Druzes, the Alawites, and the Christians, did not receive their own state.[56]

Immigration from Turkey

Waves of Kurdish Tribes and their families arrived into Syria originally came from Turkey in the 1920s.[57] Kurdish immigration waves to Syria's Jazira province started immediately after WWI. After the war, the construction of road networks and the railway extension to Nusaybin have intensified the Kurdish immigration from the Anatolian mountains to Syrian Jazirah.[28] After that, massive waves of Kurds fled their homes in the mountains of Turkey[28] after the failed Kurdish rebellions in Kemalist Turkey. It is estimated that 25,000 Kurds fled at this time to Syria, under French Mandate authorities, who encouraged their immigration,[29] and granted them Syrian citizenship.[58] The French official reports show the existence of at most 45 Kurdish villages in Jazira prior to 1927. In 1927, Hadjo Agha, the chief of the powerful Kurdish tribe Havergan, arrived with more than 600 families in Qubour el-Bid (later renamed al-Qahtaniyah).[28] The mandatory authorities continued to encourage Kurdish immigration into Syria, and a new significant wave of refugees arrived in 1929.[30] The number of Kurds settled in the Jazira province during the 1920s was estimated between 20,000[59] and 25,000.[29] With the continuous intensive immigration the villages numbered between 700 and 800 in 1939.[30] Consequently, Kurds became majority in the districts of Tigris (later renamed al-Malikiyah) and Qamishli, while Arabs remained the majority in Hasakah district.[28] Immigration from Turkey was not limited to the Jazira area. In the 1930s, Kurdish Alevis who fled the persecution of the Turkish army during the Dersim massacre, settled in Mabeta.[60]

French Mandate

Under the French Mandate of Syria, newly-arriving Kurds were granted citizenship by French Mandate authorities[61] and enjoyed considerable rights as the French Mandate authority encouraged minority autonomy as part of a divide and rule strategy and recruited heavily from the Kurds and other minority groups, such as Alawite and Druze, for its local armed forces.[62] n 1936, the French forces bombarded Amuda. On 13 August 1937, in a revenge attack, Kurdish tribes sided with Damascus and about 500 men from the Dakkuri, Milan, and Kiki tribes led by the Kurdish tribal leader Sa'ed Agha al-Dakkuri attacked the then predominantly Christian Amuda[63] and burned the town.[64] The town was destroyed and the Christian population, about 300 families, fled to the towns of Qamishli and Hasakah.[65]

Kurdish demands for autonomy

Early demands for a Kurdish autonomy came from the Kurdish deputy Nuri Kandy of Kurd Dagh, who asked the authorities of the French mandate to grant an administrative autonomy to all the areas with a Kurdish majority in 1924. Also the Kurdish tribes of the Barazi Confederation demanded autonomy for the Kurdish regions within the French Mandate.[66] But their requests were not fulfilled by the French at the time.[67] Between December 1931 and January 1932, the first elections under the new Syrian constitution were held.[68] Among the deputies there were three members of the Syrian Kurdish nationalist Xoybûn (Khoyboun) party from the three different Kurdish enclaves in Syria: Khalil bey Ibn Ibrahim Pacha (Jazira province), Mustafa bey Ibn Shahin (Jarabulus) and Hassan Aouni (Kurd Dagh).[69]

In the mid-1930s, there arose a new autonomist movement in the Jazira province among Kurds and Christians. The Kurdish leaders Hajo Agha, Kaddur Bey, and Khalil Bey Ibrahim Pasha. Hajo Agha was the Kurdish chief of the Heverkan[28] tribal confederation and one of the leaders of the Kurdish nationalist party Xoybûn (Khoyboun). He established himself as the representative of the Kurds in Jazira[28] maintaining the coalition with the Christian notables, who were represented by the Syriac Catholic Patriarch Ignatius Gabriel I Tappouni and Michel Dôme the Armenian Catholic president of the Qamishli municipality. The Kurdish-Christian Coalition wanted French troops to stay in the province in case of Syrian independence, as they feared the nationalist Damascus government would replace minority officials by Muslim Arabs from the capital. The French authorities, although some in their ranks had earlier encouraged this anti-Damascus movement, refused to consider any new status of autonomy inside Syria and even annexed the Alawite State and the Jabal Druze State to the Syrian Republic.[70]

Syrian independence

Two early presidents, Husni Zaim and also Adib Al Shishakli, were of Kurdish origin, but they didn't identify as Kurds nor did they speak Kurdish.[71] Shishakli even initiated the policy of prohibiting the Kurdish culture.[71] Osman Sabri and Hamza Diweran along with some Kurdish politicians, founded the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Syria (KDPS) in 1957.[72] The objectives of KDPS were promotion of Kurdish cultural rights, economic progress and democratic change. Following their demands for the recognition of the Kurdish cultural rights, the Party got suppressed by the United Arab Republic and the possession of Kurdish publications or music was enough to be sent to be detained.[73] KDPS was never legally recognized by the Syrian state and remains an underground organization, especially after a crackdown in 1960 during which several of its leaders were arrested, charged with separatism and imprisoned. After the failure of Syrian political union with Egypt in 1961,[73] Syria was declared an Arab Republic in the interim constitution.

Syrian Arab Republic

Jazira census

On 23 August 1962, the government conducted a special population census only for the province of Jazira based on reports of illegal infiltration of tens of thousands of Turkish Kurds into Syria.[74] As a result, around 120,000 Kurds in Jazira (20% of Syrian Kurds) were stripped of their Syrian citizenship even though they were in possession of Syrian identity cards.[75][76] The inhabitants who had Syrian identity cards were told to hand them over to the administration for renewal. However, many of those Kurds who submitted their cards received nothing in return. Many were arbitrarily categorized as ajanib ('foreigners'), while others who did not participate in the census were categorized as maktumin ('unregistered'), an even lower status than the ajanib; for all intents and purposes,[76] these unregistered Kurds did not exist in the eyes of the state. They could not get jobs, become educated, own property or participate in politics.[76] In some cases, classifications varied even within Kurdish families: parents had citizenship but not their children, a child could be a citizen but not his or her brothers and sisters. Those Kurds who lost their citizenship were often dispossessed of their lands, which were given by the state to Arab and Assyrian settlers.[77] A media campaign was launched against the Kurds with slogans such as Save Arabism in Jazira! and Fight the Kurdish Menace!.[78]

These policies in the Jazira region coincided with the beginning of Barzani's uprising in Iraqi Kurdistan and discovery of oilfields in the Kurdish inhabited areas of Syria. In June 1963, Syria took part in the Iraqi military campaign against the Kurds by providing aircraft, armoured vehicles and a force of 6,000 soldiers. Syrian troops crossed the Iraqi border and moved into the Kurdish town of Zakho in pursuit of Barzani's fighters[79]

Arab cordon

Syrian policies in the 1970s led to Arabs resettling in majority Kurdish areas.[80] In 1965, the Syrian government decided to create an Arab cordon (Hizam Arabi) in the Jazira region along the Turkish border. The cordon was along the Turkish-Syrian border and 10–15 kilometers wide,[81] stretched from the Iraqi border in the east to Ras Al-Ain in the west. The implementation of the Arab cordon plan began in 1973 and Bedouin Arabs were brought in and resettled in Kurdish areas. The toponymy of the area such as village names were Arabized. According to the original plan, some 140,000 Kurds had to be deported to the southern desert near Al-Raad. Although Kurdish farmers were dispossessed of their lands, they refused to move and give up their houses. Among these Kurdish villagers, those who were designated as alien were not allowed to own property, to repair a crumbling house or to build a new one.[82] In 1976 the further implementation of the arabization policy along the Turkish border was officially dropped by Hafez al Assad. The achieved demographic changes were not reverted,[81] and in 1977 a ban on non-arabic place names was issued.[83]

Newroz protests

In March 1986, a few thousand Kurds wearing Kurdish costume gathered in the Kurdish part of Damascus to celebrate the spring festival of Newroz. Police warned them that Kurdish dress was prohibited and they fired on the crowd leaving one person dead. Around 40,000 Kurds took part in his funeral in Qamishli. Also in Afrin, three Kurds were killed during the Newroz demonstrations.[84] After the protests, the Syrian government prohibited the Newroz festivities and established a new holiday on the same day, honoring the mothers.[85]

Qamishli riots

After an incident in a football stadium in Qamishli, 65 people were killed and more than 160 were injured in days of clashes starting from 12 March. Kurdish sources indicated that Syrian security forces used live ammunition against civilians after clashes broke out at a football match between Kurdish fans of the local team and Arab supporters of a visiting team from the city of Deir al-Zor. The international press reported that nine people were killed on 12 March. According to Amnesty International hundreds of people, mostly Kurds, were arrested after the riots. Kurdish detainees were reportedly tortured and ill-treated. Some Kurdish students were expelled from their universities, reportedly for participating in peaceful protests.[88]

KNAS (Kurdnas) formation

The Kurdistan National Assembly of Syria was formed to represent Syrian Kurds based on two major conferences, one at the US Senate in March 2006 and the other at the EU parliament in Brussels in 2006. The Kurdistan National Assembly of Syria (KNAS) seeks democracy for Syria and supports granting equal rights to Kurds and other Syrian minorities. They seek to transform Syria into a federal state, with a democratic system and structure for the federal government and provincial governments.

Syrian Civil War

_Kurdish_Syria.jpg.webp)

Following the Tunisian Revolution and the Egyptian Revolution, 4 February 2011 was declared a Day of Rage in Syria by activists through Facebook. Few turned out to protest, but among the few were Kurdish demonstrators in the northeast of the country.[89] On 7 October 2011, Kurdish leader Mashaal Tammo was gunned down in his apartment by masked men widely believed to be government agents. During Tammo's funeral procession the next day in the town of Qamishli, Syrian security forces fired into a crowd of more than 50,000 mourners, killing five people.[90] According to Tammo's son, Fares Tammo, "My father's assassination is the screw in the regime's coffin. They made a big mistake by killing my father."[91] Since then, Kurdish demonstrations became a routine part of the Syrian uprising.[92] In June 2012, the Syrian National Council (SNC), the main opposition group, announced Abdulbaset Sieda, an ethnic Kurd, as their new leader.[93]

Kurdish rebellion

Protests in the Kurdish inhabited areas of Syria evolved into armed clashes after the opposition Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and Kurdish National Council (KNC) signed a cooperation agreement on 12 July 2012 that created the Kurdish Supreme Committee as the governing body of all Kurdish controlled areas.[94][95][96]

Under the administration of the Kurdish Supreme Committee, the People's Protection Units (YPG) were created to control the Kurdish inhabited areas in Syria. On 19 July, the YPG captured the city of Kobanê, and the next day captured Amuda and Afrin.[97] The KNC and PYD afterwards formed a joint leadership council to run the captured cities.[97] By 24 July, the Syrian towns of Al-Malikiyah), Ras al-Ayn, Al-Darbasiyah and Al-Muabbada had also come under the control of the People's Protection Units. The only major cities with significant Kurdish populations that remained under government control were Hasaka and Qamishli.[98][99]

Kurdish-inhabited Afrin Canton has been occupied by the Turkish Armed Forces and Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army since the Turkish military operation in Afrin in early 2018.[100] Between 150,000 and 200,000 people were displaced due to the Turkish intervention.[101]

On 9 October 2019, Turkey started bombarding Kurdish-controlled regions of Syria for a planned invasion called Operation Peace Spring.[102]

Mistreatment by Syrian government

International and Kurdish human rights organizations have accused the Syrian government of discriminating against the Kurdish minority.[103][104][105] Amnesty International also reported that Kurdish human rights activists are mistreated and persecuted.[106]

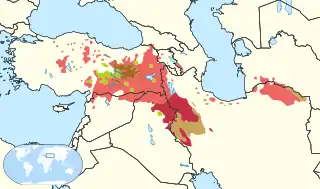

Language

|

Northern Kurdish

Central Kurdish

Southern Kurdish (Gorani is included) |

Zazaki

mixed dialect areas

|

The Kurdish language is the second most spoken language in Syria, after Arabic.[107]

The Kurds often speak the Kurdish language in public, unless all those present do not. According to the Human Rights Watch, Kurds in Syria are not allowed to officially use the Kurdish language, are not allowed to register children with Kurdish names, are prohibited to start businesses that do not have Arabic names, are not permitted to build Kurdish private schools and are prohibited from publishing books and other materials written in Kurdish.[108] In 1988 it was prohibited also to sing in non-arabic language at weddings or festivities.[109]

There are also some "nawar people" (gypsies) who speak Kurdish and call themselves Kurds in some regions.[110]

Decree 768

The decree 768 of the year 2000, prohibited shops to sell cassettes or videos in Kurdish language. The decree also encouraged to implement older restrictions of the Kurdish language.[111]

Citizenship

In 1962, 20 percent of Syria's Kurdish population were stripped of their Syrian citizenship following a very highly controversial census raising concerns among human rights groups. According to the Syrian government, the reason for this enactment was due to groups of Kurds infiltrating the Al-Hasakah Governorate in 1945. The Syrian government claims that the Kurds came from neighboring countries, especially Turkey, and crossed the Syrian border illegally. The government claims that these Kurds settled down, gradually, in the region in cities like Amuda and Qamishli until they accounted for the majority in some of these cities. The government also claims that many Kurds were capable of registering themselves illegally in the Syrian civil registers. The government further speculated that Kurds intended to settle down and acquire property, especially after the issue of the agricultural reform law, to benefit from land redistribution.[108] However, according to Human Rights Watch, the Syrian government falsely claimed that many of the Kurds who were the original inhabitants of the land were foreigners, and in turn, violated their human rights by stripping them of their Syrian citizenship.[112]

As a result of government claims of an increase in illegal immigration, the Syrian government decided to conduct a general census on 5 October 1962 in the governorate with claims that its sole purpose was to purify registers and eliminate the alien infiltrators. As a result, the verified registrations of the citizens of Syria were included in the new civil registers. The remaining, which included 100,000 Kurds, were registered as foreigners (or "ajanib") in special registers.[108][113] Many others did not participate in the census through choice or other circumstances; they are known as "maktoumeen", meaning "unrecorded".[113] Since then, the number of stateless Kurds has grown to more than 200,000.[114] According to Refugees International, there are about 300,000 Kurdish non-citizens in Syria; however, Kurds dispute this number and estimate about 500,000. An independent report has confirmed that there are at least 300,000 non-citizen Kurds living in Syria.[113]

According to the Human Rights Watch, by many accounts, the special census was carried out in an arbitrary manner separating members of the same families and classifying them differently. HRW claims that some Kurds in the same family became citizens while others became foreigners suggesting an inaccuracy in the Syrian government's process; HRW also alleges that some of the Kurds who had served in the Syrian army lost citizenship while those who bribed officials kept theirs.[112] Stateless Kurds also do not have the option of legally relocating to another country because they lack passports or other internationally recognized travel documents. In Syria, other than in the governorate of Al-Hasakah, foreigners cannot be employed at government agencies and state-owned enterprises; they may not legally marry Syrian citizens. Kurds with foreigner status do not have the right to vote in elections or run for public office, and when they attend universities they are often persecuted and cannot be awarded with university degrees.[113] non-citizens Kurds living in Syria are not awarded school certificates and are often unable to travel outside of their provinces.[113]

In April 2011, the President signed Decree 49 which provides citizenship for Kurds who were registered as foreigners in Hasaka.[115] However, a recent independent report has suggested that the actual number of non-citizens Kurds who obtained their national ID cards following the decree does not exceed 6,000, leaving the remainder of 300,000 non-citizens Kurds living in Syria in a state of uncertainty.[113] One newly nationalized Kurd has been reported as saying: ‘I’m pleased to have my ID card .... But not until the process is completed will I truly trust the intentions of this action. Before my card is activated, I must have an interview, no doubt full of interrogation and intimidation, with State Security. Citizenship should not be a privilege. It is my right.’[113] According to one researcher, the Kurdish street perceived the measure of providing citizenship as 'not well-intentioned, but simply an attempt to distance Kurds from the developing protest movement of the Syrian Revolution.'[116]

Influential Syrian Kurds

Politicians

- Ibrahim Hananu (1869–1935), Ottoman municipal official and later a leader of a revolt against the French presence in northern Syria.

- Adib Shishakli (1909–1964), Syrian military leader and President of Syria (1953–1954).

- Ata Bey al-Ayyubi (1877–1951), Prime Minister of Syria (1936) and President of Syria (1943).

- Husni al-Za'im (1897–1949), Prime Minister and President of Syria (1949).

- Husni al-Barazi (1895–1975), Prime Minister of Syria (1942–1943)

- Muhsin al-Barazi (1904–1949), Prime Minister of Syria (1949).

- Khalid Bakdash (1912–1995), leader (1936–1995) of the Syrian Communist Party.

- Qadri Jamil (born 1952), Kurdish politician and one of the leaders of the People's Will Party and the Popular Front for Change and Liberation.

- Mahmoud al-Ayyubi (born 1932), Prime Minister of Syria (1972–1976)

- Muhammad Mustafa Mero (born 1941), Prime Minister of Syria (2000–2003).

- Daham Miro (1921–2010), Kurdish political leader and former chairman of the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Syria.

- Mashaal Tammo (1958–2011), Kurdish Political leader and founder of the Kurdish Future Movement.

Singers

- Ciwan Haco (born 1957), Kurdish singer.

Authors

- Cigerxwîn (1903–1984), influential Kurdish writer and poet.

- Osman Sabri (1905–1993), Kurdish poet, writer and journalist.

- Haitham Hussein (born 1978), Novelists and Journalist.

- Salim Barakat (born 1951), Novelist and poet.

Scholars

- Ahmed Kuftaro (1915–2004), Grand Mufti (1964–2004), the highest Sunni authority in the country.

- Mohamed Said Ramadan Al-Bouti (1929–2013), influential Islamic scholar.

- Muhammad Kurd Ali (1876–1953), historian and literary critic.

Actors

- Muna Wassef (born 1942), actress.

- Khaled Taja (1939–2012), actor.

- Caresse Bashar (born 1976), actress of Kurdish origin.

Sports

- Jwan Hesso (born 1982), Syrian footballer.

- Kawa Hesso (born 1984), Syrian footballer.

- Haytham Kajjo (1976–2002), Syrian footballer.

- Muhammad Albicho (born 1985), Syrian footballer.

- Ahmad Al Salih (born 1989), Syrian footballer.

See also

References

- 1 2 World Factbook (Online ed.). Langley, Virginia: US Central Intelligence Agency. 2019. ISSN 1553-8133. Archived from the original on 1 June 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2019. CIA estimates are as of June 2019 "Ethnic groups: Sunni Arab ~50%, Alawite ~15%, Kurd ~10%, Levantine ~10%, other ~15% (includes Druze, Ismaili, Imami, Nusairi, Assyrian, Turkoman, Armenian)"

- 1 2 "Who are the Kurds?". BBC News (Online ed.). 31 October 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ↑ Darke, Diana (1 January 2010). Syria. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 9781841623146.

- ↑ "Syria rejects Russian proposal for Kurdish federation". Al-Monitor. 24 October 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- 1 2 Vanly, Ismet Chérif; Vanly, Ismet Cheriff (1977). "Coup d'oeil sur la culture nationale Kurde". Oriente Moderno. 57 (9/10): 445. doi:10.1163/22138617-0570910007. ISSN 0030-5472. JSTOR 25816505.

- ↑ "Syrian Kurds celebrate Kurdish Language Day". Kurdistan24. 16 May 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ↑ "Alawite Kurds in Syria: Ethnic discrimination and dectarian privileges. By Maya Ehmed". Ekurd.net. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- 1 2 Shoup, John A. (2018), "Syria", The History of Syria, ABC-CLIO, p. 6, ISBN 978-1440858352,

Syria has several other ethnic groups, the Kurds... they make up an estimated 9 percent...Turkomen comprise around 4-5 percent of the total population. The rest of the ethnic mix of Syria is made of Assyrians (about 4 percent), Armenians (about 2 percent), and Circassians (about 1 percent).

- ↑ "Turkey's Syria offensive explained in four maps". BBC.com. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

Kurds make up between 7% and 10% of Syria's population.

- 1 2 "Who are Syria's minority groups?". SBS News (Online ed.). Special Broadcasting Service. 11 September 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2017. Kurds are the largest ethnic minority in Syria, constituting around 10 per cent of the population – around 2 million of the pre-conflict population of around 22 million.

- ↑ Kingsley, Patrick (14 October 2019). "Who Are the Kurds, and Why Is Turkey Attacking Them in Syria?". New York Times (Online ed.). Retrieved 5 August 2020.

Kurds are the largest ethnic minority in Syria, making up between 5 and 10 percent of the Syrian population of 21 million in 2011

- 1 2 Fabrice Balanche (2018). Sectarianism in Syria's Civil War (PDF) (Online ed.). Washington, DC: The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 25 June 2019. In this atlas, French geographer Balanche suggests that "As of 2010, Syria’s population was roughly 65% Sunni Arab, 15% Kurdish, 10% Alawite, 5% Christian, 3% Druze, 1% Ismaili, and 1% Twelver Shia." (page 13) "The number of Kurds in Syria is often underestimated by analysts, who tend to cap them at 10% of the population. In fact, they are closer to 15%."(page 16) The 2018 breakdown is 1% Sunni Arab, 16% Kurdish, 13% Alawite, 3% Christian, 4% Druze, 1% Ismaili, 1% Twelver Shia, 1% Turkmen (page 22) Balanche also refers to his Atlas du ProcheOrient Arabe (Paris: Presses de l’Université Paris-Sorbonne, 2011), p. 36."

- ↑ Radpey, Loqman (September 2016). "Kurdish Regional Self-rule Administration in Syria: A new Model of Statehood and its Status in International Law Compared to the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq". Japanese Journal of Political Science. 17 (3): 468–488. doi:10.1017/S1468109916000190. ISSN 1468-1099.

Some 15% to 17% of the Syrian population is Kurdish. Whether they can achieve statehood will depend on a reading of international law and on how the international community reacts.

- 1 2 3 4 Storm, Lise (2005). "Ethnonational Minorities in the Middle East Berbers, Kurds, and Palestinians". A Companion to the History of the Middle East. Utrecht: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 475. ISBN 1-4051-0681-6.

- ↑ Krajeski, Jenna (2016). "The future of Kurdistan". Great Decisions: 30. ISSN 0072-727X. JSTOR 44214818 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ "Syria: End Persecution of Kurds". Human Rights Watch. 26 November 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ↑ Ian Black (16 July 2010). "Syrian human rights record unchanged under Assad, report says]". The Guardian.

- ↑ Morris, Loveday (9 August 2012). "Syrian President Bashar al-Assad accused of arming Kurdish separatists for attacks against Turkish government". The Independent. London.

- ↑ "Syrian Kurdish moves ring alarm bells in Turkey". Reuters. 24 July 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "Kurds seek autonomy in a democratic Syria". BBC World News. 16 August 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ↑ "The Kurds are creating a state of their own in northern Syria". The Economist. 23 May 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ↑ Tejel (2009) p.100

- ↑ Schmidinger, Thomas (22 March 2017). Krieg und Revolution in Syrisch-Kurdistan: Analysen und Stimmen aus Rojava (in German). Mandelbaum Verlag. p. 160. ISBN 978-3-85476-665-0.

- ↑ Kingsley, Patrick (14 October 2019). "Who Are the Kurds, and Why Is Turkey Attacking Them in Syria?". New York Times. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ↑ Tank, Pinar (2017). "Kurdish Women in Rojava: From Resistance to Reconstruction". Die Welt des Islams. 57 (3–4): 412. doi:10.1163/15700607-05734p07. ISSN 0043-2539. JSTOR 26568532.

- ↑ Tejel, Jordi (2009). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. London: Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-203-89211-4.

- ↑ Jordi Tejel, translated from the French by Emily Welle; Welle, Jane (2009). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society (1. publ. ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 10. ISBN 978-0-203-89211-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Fevret, Maurice; Gibert, André (1953). "La Djezireh syrienne et son réveil économique". Revue de géographie de Lyon (in French). 28 (28): 1–15. doi:10.3406/geoca.1953.1294. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 McDowell, David (2005). A Modern History of the Kurds (3. revised and upd. ed., repr. ed.). London [u.a.]: Tauris. p. 469. ISBN 1-85043-416-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tejel, Jordi (2009). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. London: Routledge. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-203-89211-4.

- ↑ Yildiz, Kerim (2005). The Kurds in Syria: The Forgotten People (1. publ. ed.). London [etc.]: Pluto Press, in association with Kurdish Human Rights Project. pp. 25. ISBN 0-7453-2499-1.

- 1 2 Gorgas, Jordi Tejel (2007). Le mouvement kurde de Turquie en exil: continuités et discontinuités du nationalisme kurde sous le mandat français en Syrie et au Liban (1925–1946) (in French). Peter Lang. p. 41. ISBN 978-3-03911-209-8.

- ↑ Yildiz, Kerim (2005). The Kurds in Syria : the forgotten people (1. publ. ed.). London [etc.]: Pluto Press, in association with Kurdish Human Rights Project. pp. 25. ISBN 0745324991.

- ↑ "Community Post: 5 Trailblazing Medical Students Of The 19th Century". BuzzFeed Community. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ↑ Salibi, Kamal S. (1990). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. University of California Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-520-07196-4.

- ↑ Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-134-09643-5.

- ↑ Winter, Stefan (2006). "The Other "Nahḍah": The Bedirxans, the Millîs and the Tribal Roots of Kurdish Nationalism in Syria". Oriente Moderno. 25 (86) (3): 461–474. doi:10.1163/22138617-08603003. JSTOR 25818086.

- ↑ Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: history, politics and society (1. publ. ed.). London: Routledge. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-415-42440-0.

- ↑ Winter, Stefan (2009). "Les Kurdes de Syrie dans les archives ottomanes (XVIIIe siècle)". Études Kurdes. 10: 125–156.

- ↑ Carsten Niebuhr (1778). Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern. (Mit Kupferstichen u. Karten.) – Kopenhagen, Möller 1774–1837 (in German). p. 419.

- ↑ Carsten Niebuhr (1778). Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern. (Mit Kupferstichen u. Karten.) – Kopenhagen, Möller 1774–1837 (in German). p. 389.

- ↑ Stefan Sperl, Philip G. Kreyenbroek (1992). The Kurds a Contemporary Overview. London: Routledge. pp. 145–146. ISBN 0-203-99341-1.

- ↑ Özoğlu, Hakan (2001). ""Nationalism" and Kurdish Notables in the Late Ottoman–Early Republican Era". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 33 (3): 389. doi:10.1017/S0020743801003038. ISSN 0020-7438. JSTOR 259457. S2CID 154897102.

- ↑ Hovannisian, Richard G. (2011). The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412835923.

- 1 2 R. S. Stafford (2006). The Tragedy of the Assyrians. Gorgias Press, LLC. pp. 24–25. ISBN 9781593334130.

- ↑ Joan A. Argenter, R. McKenna Brown (2004). On the Margins of Nations: Endangered Languages and Linguistic Rights. Institut d'Estudis Catalans. p. 199. ISBN 9780953824861.

- ↑ Travis, Hannibal. Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2010, 2007, pp. 237–77, 293–294.

- ↑ Hovannisian, Richard G. (31 December 2011). The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-3592-3.

- ↑ Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. ISBN 9781134096435.

- ↑ Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society (PDF). pp. 25–29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ Winter, Stefan (2005). "Les Kurdes du Nord-Ouest syrien et l'État ottoman, 1690–1750". In Afifi, Mohammad (ed.). Sociétés rurales ottomanes. Cairo: IFAO. pp. 243–258. ISBN 2724704118.

- ↑ Winter, Stefan (2006). "The Other Nahdah: The Bedirxans, the Millîs, and the Tribal Roots of Kurdish Nationalism in Syria". Oriente Moderno. 86 (3): 461–474. doi:10.1163/22138617-08603003.

- ↑ Klein, Janet (2011). The Margins of Empire: Kurdish Militias in the Ottoman Tribal Zone. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7570-0.

- ↑ Abadie, Maurice (1959). Türk Verdünü, Gaziantep: Antep'in dört muhasarası. Aintab: Gaziantep Kültür Derneği. p. 5. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ↑ Yildiz, Kerim (2005). The Kurds in Syria : the forgotten people (1. publ. ed.). London [etc.]: Pluto Press, in association with Kurdish Human Rights Project. pp. 13–15. ISBN 0745324991.

- ↑ Schmidinger, Thomas (22 March 2017). Krieg und Revolution in Syrisch-Kurdistan: Analysen und Stimmen aus Rojava (in German). Mandelbaum Verlag. p. 160. ISBN 978-3-85476-665-0.

- ↑ Youssef M. Choueiri (2005). A companion to the history of the Middle East (Hardcover ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 475. ISBN 1405106816.

- ↑ Kreyenbroek, Philip G.; Sperl, Stefan (1992). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. London: Routledge. pp. 147. ISBN 0-415-07265-4.

- ↑ Simpson, John Hope (1939). The Refugee Problem: Report of a Survey (First ed.). London: Oxford University Press. p. 458. ASIN B0006AOLOA.

- ↑ "derStandard.at". DER STANDARD. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ↑ Dawn Chatty (2010). Displacement and Dispossession in the Modern Middle East. Cambridge University Press. pp. 230–232. ISBN 978-1-139-48693-4.

- ↑ Yildiz, Kerim (2005). The Kurds in Syria : the forgotten people (1. publ. ed.). London [etc.]: Pluto Press, in association with Kurdish Human Rights Project. p. 25. ISBN 0745324991.

- ↑ Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society (PDF). pp. 25–29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ↑ Watenpaugh, Keith David (2014). Being Modern in the Middle East: Revolution, Nationalism, Colonialism, and the Arab Middle Class. Princeton University Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-4008-6666-3.

- ↑ John Joseph, Muslim-Christian Relations and Inter-Christian Rivalries in the Middle East, p. 107.

- ↑ Tejel, pp.27–28

- ↑ Tejel, p.28

- ↑ The 1930 Constitution is integrally reproduced in: Giannini, A. (1931). "Le costituzioni degli stati del vicino oriente" (in French). Istituto per l’Oriente. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ Tachjian, Vahé (2004). La France en Cilicie et en Haute-Mésopotamie: aux confins de la Turquie, de la Syrie et de l'Irak, 1919–1933 (in French). Paris: Editions Karthala. p. 354. ISBN 978-2-84586-441-2. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ↑ Jordi Tejel Gorgas, "Les territoires de marge de la Syrie mandataire : le mouvement autonomiste de la Haute Jazîra, paradoxes et ambiguïtés d’une intégration" nationale" inachevée (1936–1939)" (The territory margins of the Mandatory Syria : the autonomist movement in Upper Jazîra, paradoxs and ambiguities of an uncompleted "national" integration, 1936–39), Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée, 126, November 2009, p. 205-222

- 1 2 Gunter, Michael M. (2016). The Kurds: A Modern History. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-558766150.

- ↑ "The Kurdish Democratic Party in Syria (al-Parti)". Carnegie Middle East Center. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- 1 2 Hassanpour, Amir (1992). Nationalism and Language in Kurdistan. San Francisco: Mellen Research University Press. p. 137. ISBN 0773498168.

- ↑ McDowall, David. Modern History of the Kurds, I. B. Tauris & Company, Limited, 2004. pp. 473–474.

- ↑ Hassanpour, Amir (1992). Nationalism and Language in Kurdistan. San Francisco: Mellen Research University Press. pp. 137–138. ISBN 0773498168.

- 1 2 3 Gunter, Michael M. (2016), p.97

- ↑ Tejel, p. 51

- ↑ Tejel, p. 52

- ↑ I. C. Vanly, The Kurds in Syria and Lebanon, In The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview, Edited by P.G. Kreyenbroek, S. Sperl, Chapter 8, Routledge, 1992, ISBN 0-415-07265-4, pp.151–52

- ↑ Philip G. Kreyenbroek; Stefan Sperl (1992). "Chapter 8: The Kurds in Syria and Lebanon". The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. Routledge. pp. 157, 158, 161. ISBN 978-0-415-07265-6.

- 1 2 Hassanpour, Amir (1992). Nationalism and Language in Kurdistan. San Francisco: Mellen Research University Press. p. 139. ISBN 0773498168.

- ↑ I. C. Vanly, The Kurds in Syria and Lebanon, In The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview, Edited by P.G. Kreyenbroek, S. Sperl, Chapter 8, Routledge, 1992, ISBN 0-415-07265-4, pp.157, 158, 161

- ↑ Tejel, Jordi (29 August 2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-134-09643-5.

- ↑ I. C. Vanly, The Kurds in Syria and Lebanon, In The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview, Edited by P.G. Kreyenbroek, S. Sperl, Chapter 8, Routledge, 1992, ISBN 0-415-07265-4, pp.163–164

- ↑ Tejel, Jordi (29 August 2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-09643-5.

- ↑ "www.amude.com". Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ↑ "With A Dose Of Caution, Kurds Oppose Syrian Regime". NPR.org. 5 April 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ↑ Syria: Address Grievances Underlying Kurdish Unrest, HRW, 19 March 2004.

- ↑ Cajsa Wikstrom. "Syria: 'A kingdom of silence'". Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ↑ Syria Funeral Shooting: Forces Open Fire On Mashaal Tammo Mourners, Huffington Post, 10/8/11

- ↑ Thousands of Kurds could awaken against Syrian regime, By Adrian Blomfield, 9 October 2011

- ↑ Syria's Kurds: part of the revolution?, Guardian, By Thomas McGee, 26 April 2012

- ↑ MacFarquhar, Neil (10 June 2012). "Syrian Forces Shell Cities as Opposition Picks Leader". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Syrian Kurds Try to Maintain Unity". Rudaw. 17 July 2012. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "Syria: Massive protests in Qamishli, Homs". CNTV. 19 May 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "Syrian Kurdish Official: Now Kurds are in Charge of their Fate". Rudaw. 27 July 2012. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- 1 2 "More Kurdish Cities Liberated As Syrian Army Withdraws from Area". Rudaw. 20 July 2012. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "Armed Kurds Surround Syrian Security Forces in Qamishli". Rudaw. 22 July 2012. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "Girke Lege Becomes Sixth Kurdish City Liberated in Syria". Rudaw. 24 July 2012. Archived from the original on 29 November 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "Syria's war of ethnic cleansing: Kurds threatened with beheading by Turkey's allies if they don't convert to extremism". The Independent. 12 March 2018.

- ↑ "Displaced Kurds from Afrin need help, activist says". The Jerusalem Post. 26 March 2018.

- ↑ "Tens of thousands flee as Turkey presses Syria offensive". The Irish Times. 10 October 2019.

- ↑ ""Support Kurds", 14 May 2010". Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ "Kurdish Organization for Human Rights in Austria," 14 December 2010 Memorandum of Kurds in syria "Mesopotamische Gesellschaft « Memorandum of KURDS IN SYRIA". Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ↑ For Zion's sake Yehuda Zvi Blum, Associated University Presse, ISBN 0-8453-4809-4 (1987) p. 220

- ↑ "amnestyusa.org". Archived from the original on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ Behnstedt, Peter (2008), "Syria", Encyclopedia of Arabic language and linguistics, vol. 4, Brill Publishers, p. 402, ISBN 978-90-04-14476-7

- 1 2 3 "hrw.org". Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ "Syria, The silenced Kurds". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ↑ Tarlan, Kemal Vural, ed. (2017), The Dom, The "Other" Asylum Seekers From Syria: Discrimination, Isolation and Social Exclusion: Syrian Dom Asylum Seekers in the Crossfire (PDF), Kırkayak Kültür Sanat ve Doğa Derneği, p. 21, archived from the original (PDF) on 18 June 2018, retrieved 17 June 2018

- ↑ Tejel, Jordi (29 August 2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-1-134-09643-5.

- 1 2 "Syria Silenced Kurds, Human Rights Watch". Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Documentary On The non-citizens Kurds of Syria". Rudaw. 26 September 2011. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012.

- ↑ voanews.com Archived 14 September 2008 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- ↑ Legislative Decree on Granting Syrian Nationality to People Registered in Registers of Hasaka Foreigners Archived 5 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, SANA, 8 April 2011

- ↑ The Stateless Kurds of Syria: Ethnic Identity and National I.D., Thomas McGee, 2014

Further reading

- Tejel, Jordi (2009). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415424400.