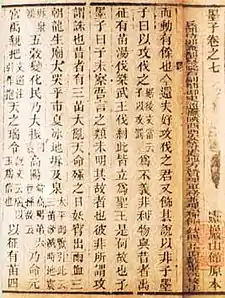

7th volume | |

| Author | (trad.) Mo Di |

|---|---|

| Original title | 墨子 |

| Translator | Burton Watson A. C. Graham Mei Yi-pao Ian Johnston |

| Country | China |

| Language | Classical Chinese |

| Genre | Philosophy |

Publication date | 5th–3rd centuries BC |

Published in English | 1929 |

| Media type | manuscript |

| 181.115 | |

| LC Class | B128 .M6 |

| Translation | Mozi at Wikisource |

| Mozi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) "Mozi" in seal script (top) and regular (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 墨子 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "[The Writings of] Master Mo" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Mozi (Chinese: 墨子), also called the Mojing (Chinese: 墨經) or the Mohist canon,[1][2] is an ancient Chinese text from the Warring States period (476–221 BC) that expounds the philosophy of Mohism. It propounds such Mohist ideals as impartiality, meritocratic governance, economic growth and aversion to ostentation, and is known for its plain and simple language.

The book's chapters can be divided into several categories: a core group of 31 chapters, which contains the basic philosophic ideas of the Mohist school; several chapters on logic, which are among the most important early Chinese texts on logic and are traditionally known as the "Dialectical Chapters"; five sections containing stories and information about Mozi and his followers; and eleven chapters on technology and defensive warfare, on which the Mohists were expert and which are valuable sources of information on ancient Chinese military technology.[3] There are also two other minor sections: an initial group of seven chapters that are clearly of a much later date, and two anti-Confucian chapters, only one of which has survived.

The Mohist philosophical school died out in the 3rd century BC, and copies of the Mozi were not well preserved. The modern text has been described as "notoriously corrupt". Of the Mozi's 71 original chapters, 18 have been lost and several others are badly fragmented.[4][5]

Authorship

The Mozi, as well as the entire philosophical school of Mohism, is named for and traditionally ascribed to Mo Di, usually known as "Mozi" (Mandarin Chinese: Mòzǐ 墨子, "Master Mo"). Mozi is a figure from the 5th century BC about whom nothing is reliably known.[6] Most sources describe him as being from the State of Lu—though one says that he was from the State of Song—and say that he traveled around the various Warring States trying to persuade their rulers to stop attacking each other.[3] Mozi seems to have come from a humble family,[3] and some elements of the book suggest that he may have been some type of artisan or craftsman, such as a carpenter.[6] Some scholars have theorized that the name Mo (墨), which means "ink", may not truly be a surname, but could be indicative of Mozi having undergone the branding or tattooing that was used in ancient China as a form of criminal punishment.[6][7]

Content

The Mozi originally comprised 71 chapters. However, 18 of the original chapters have been lost, and several others are damaged and fragmented. The text can be divided into a total of six sections:[8]

- Chapters 1–7: a group of miscellaneous essays and dialogues that were clearly added at a later date and are somewhat incongruous with the rest of the book.

- Chapters 8–37: a large group of chapters—of which seven are missing and three are fragmentary—that form the core Mozi chapters and elucidate the ten main philosophical doctrines of the Mohist school of thought. Mozi is frequently referenced and cited in these chapters.

- Chapters 38–39: two chapters—of which only chapter 39 survives—entitled "Against Confucianism" (Fēi Rú 非儒), containing polemical arguments against the ideals of Confucianism. These chapters are sometimes grouped with chapters 8–37.

- Chapters 40–45: a group of six chapters, often called the "Dialectical Chapters", which are some of the most unique writings of ancient China. They cover topics in logic, epistemology, ethics, geometry, optics, and mechanics. The "Dialectical Chapters" are dense and difficult, largely because the text is badly garbled and corrupted.

- Chapters 46–51: six chapters—of which chapter 51, including even its title, has been lost—that contain stories and dialogues about Mozi and his followers. These chapters are probably of somewhat later date and are probably partly fictional.

- Chapters 52–71: a group of chapters—nine of which have been lost—known as the "Military Chapters", containing instructions on defensive warfare, supposedly from Mozi to his chief disciple Qin Guli. These chapters are badly damaged and corrupted.

Selected translations

The damaged nature of the later chapters of the Mozi have made its translations highly difficult, and often requires translators to repair and re-edit the text before translating. The first Mozi translation in a Western language—the 1922 German translation of Alfred Forke—was done before these problems were well understood, and thus contains many errors in the "Dialectical" and "Military" chapters.[9] Only in the late 20th century did accurate translations of the later Mozi chapters appear:

- (in German) Alfred Forke (1922), Mê Ti: Des Socialethikers und seiner Schüler philosophische Werke, Berlin: Kommissionsverlag der Vereinigung wissenschaftlicher Verleger.

- Mei Yi-pao (1929), The Ethical and Political Works of Motse, London: Probsthain. Reprinted (1974), Taipei: Ch'eng-wen.

- Burton Watson (1963), Mo Tzu: Basic Writings, New York: Columbia University Press.

- A. C. Graham (1978), Later Mohist Logic, Ethics, and Science, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press.

- Ian Johnston (2010), The Mozi: A Complete Translation, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press.

- Chris Fraser (2020), The Essential Mòzǐ: Ethical, Political, and Dialectical Writings, New York: Oxford University Press.

Many Mozi translations in Modern Chinese and Japanese exist.

References

Citations

- ↑ Fraser, Chris (2018), "Mohist Canons", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2020-01-18

- ↑ Jun (2014), p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Knechtges (2010), p. 677.

- ↑ Graham (1993), p. 339.

- ↑ Nivison (1999), p. 762.

- 1 2 3 Nivison (1999), p. 760.

- ↑ Watson (1999), p. 64.

- ↑ See Knechtges (2010), p. 677, Graham (1993), pp. 336–37, and Nivison (1999), pp. 761–63.

- ↑ Graham (1993), p. 340.

Sources

- Works cited

- Graham, A. C. (1993). "Mo tzu 墨子". In Loewe, Michael (ed.). Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Berkeley, CA: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California Berkeley. pp. 336–41. ISBN 978-1-55729-043-4.

- Jun, Wenren (2014). Ancient Chinese Encyclopedia of Technology: Translation and Annotation of Kaogong ji, The Artificers' Record. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-26787-1.

- Knechtges, David R. (2010). "Mozi 墨子". In Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping (eds.). Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide, Part One. Leiden, South Holland: Brill. pp. 677–81. ISBN 978-90-04-19127-3.

- Nivison, David Shepherd (1999). "The Classical Philosophical Writings". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 745–812. ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- Watson, Burton (1999). "Mozi: Utility, Uniformity, and Universal Love". In de Bary, Wm. Theodore; Bloom, Irene (eds.). Sources of Chinese Tradition, Volume 1: From Earliest Times to 1600 (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. pp. 64–76. ISBN 978-0-231-10939-0.