Modesta di Pozzo di Forzi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 15, 1555[1] |

| Died | November 2, 1592[2] |

| Pen name | Moderata Fonte |

| Language | Italian |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Period | 16th century |

| Subject | Feminism |

| Notable works | The Worth of Women |

Moderata Fonte, directly translates to Modest Well[3] is a pseudonym of Modesta di Pozzo di Forzi (or Zorzi), also known as Modesto Pozzo (or Modesta, feminization of Modesto),[4] (1555–1592) was a Venetian writer and poet.[5] Besides the posthumously-published dialogues, Giustizia delle donne and Il merito delle donne (gathered in The Worth of Women, 1600), for which she is best known, she wrote a romance and religious poetry. Details of her life are known from the biography by Giovanni Niccolò Doglioni (1548-1629), her uncle, included as a preface to the dialogue.[6]

Life and History

Pozzo's parents, Girolamo da Pozzo and Marietta da Pozzo (née dal Moro),[7] died of the plague in 1556, when she was just a year old, and she and her older brother Leonardo were placed in the care of their maternal grandmother and her second husband. She spent several years in the convent of Santa Marta where, thanks to her extraordinary memory, she was often displayed as a child prodigy. She was able to repeat long sermons she had heard or read only once.[8] At the age of nine she was returned to her grandmother's family where she learned Latin and composition from her grandfather, Prospero Saraceni, a man of letters, as well as from her brother, Leonardo.[9] Her brother also taught her to read and write in Latin, draw, sing, and play the lute and harpsichord.[10] She, in addition, had informally continued her education under the guidance of Saraceni by allowing her the run of his library.[11] From 1576, in her early twenties, she would continue to have a relationship with the Saracenis as she went to go stay with their daughter, Saracena.[12]

On 15 February 1582, at twenty-seven years old, Moderata wed Filippo de’ Zorzi who was a lawyer and government official, with whom she would later have four children.[13] They had two sons, Pietro who was the oldest and Girolamo, the third born. They also had two daughters, the second born Cecilia and the youngest whose name was never released.[11] Their marriage seemed to reflect equality and mutual respect as evidenced by de’ Zorzi returning her dowry a year and a half after their wedding.[14] An official document dated October 1583 states that de’ Zorzi returns the dowry "thanks to his pure kindness and to the great love and good will that he has felt and feels for" her.[14] Likewise, Moderata Fonte describes her husband in one of her writings as a man of "virtue, goodness and integrity".[15]

These actions were significant in this time period, since women did not typically have property under their own name with which they could govern. Furthermore, the appeal for women to own property has been a longstanding debate in feminist advocacy.

Works

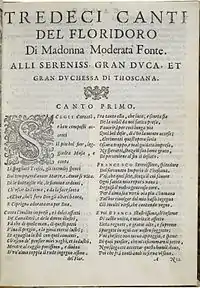

One of Fonte's first known works is a musical play performed before the Doge Da Ponte in 1581 at the festival of St. Stephen's Day. Le Feste [The Feasts] includes about 350 verses with several singing parts. Also in 1581, she published her epic poem I tredici canti del Floridoro [The Thirteen Cantos of Floridoro] dedicated to Bianca Cappello and her new husband, Francesco I de' Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany. This poem is perhaps the second chivalric work published by an Italian woman, after Tullia d’Aragona's Il Meschino, which appeared in 1560.

Moderata Fonte wrote two long religious poems, La Passione di Cristo [Christ's Passion] and La Resurrezione di Gesù Cristo nostro Signore che segue alla Santissima Passione in otava rima da Moderata Fonte [The Resurrection of Jesus Christ, our Lord, which follows the Holy Passion in octaves by Moderata Fonte]. In these works she describes in detail the emotional reactions of the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalen to Christ's death and resurrection, illustrating her deep belief in the active participation of women in the events of the Passion and Resurrection of Christ.[16]

She is perhaps best known for a composition that she worked on from the years 1588 to 1592[17] called Il Merito delle donne [On The Merit of Women], published posthumously in 1600, in which she criticizes the treatment of women by men while celebrating women's virtues and intelligence and arguing that women are superior to men,[5] but does not go as far as to appeal for sexual equality.[9] Perhaps a forerunner of consciousness raising that attempted to bring awareness to the role of men in the women question or the quelles des femmes The woman question.

When she died in 1592 at the age of thirty-seven, Pozzo had four children according to her biographer and mentor, Giovanni Nicolo Doglioni: the oldest aged ten years, the second aged eight, the third aged six and the newborn, whose birth caused her death.[18] Her husband placed a marble epitaph on her tomb which describes Pozzo as ‘femina doctissima’ [a very learned woman].

- The Worth of Women: Wherein is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Their Superiority to Men By Moderata Fonte (1997) translated by Virginia Cox. OCLC 44959387.

- Moderata Fonte (Modesta Pozzo). Floridoro: A Chivalric Romance. Ed. by Valeria Finucci. Tr. by Julia Kisacky. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006. Pp xxx, 493 (The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe). OCLC 614478182.

Giustizia delle donne (The Worth of Women: Wherein is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Their Superiority to Men)

Giustizia delle donne[19] was published after Fonte's death along with Il merito delle donne. Both literary works are influenced by Boccaccio's Decameron: they are frame stories where the characters develop their dialogues and exempla.

A group of women are talking in a venetian garden when Pasquale arrives and breaks the relaxed atmosphere by referring the last argument she has had with her husband. It leads to an inspiring conversation about "masculine behaviour" in which they complain about the unfair situations they have to face every day; they imagine twelve punishments (one per month) in order to raise awareness among men. That way, they'd have to suffer from public humiliation, they'd have to be self-sacrificing parents and be isolated from their friends and family. The most remarkable punishment is the one dedicated to silence: only women have a voice, a voice which finally lets them speak and organize society.

The most significant literary devices in this work are irony, paradoxes and references to the reader (as it happened in ancient novels). She was influenced by Plato dialogues’ rhythm and through all these procedures achieves to build up a precise portrait of the social concerns in the 16th Century.

The book is divided in 14 chapters: the first one works as an introduction or frame, the next twelve cover punishments and attacks to the masculine figure and in the last one they return to real life after their imaginary trip, but, as it happens in all trips, they come back wiser and filled with hope.

Themes and Outcomes

Impact and Contemporaries

Writing takes up arms in the disputes of the worth of women, however, the freedom of speech of the women characters of the renaissance often occur in the absence of men.[20] Literary dialogue often silenced or excluded women, however, Moderata Fonte breaks this tradition in creating the Worth of Women by the complete absence of men. In this dialogue the worth of women is not questioned, but rather the worth of men is put on trial in their garden debate. The second part of Fonte's work demonstrates what it means to become a renaissance woman through intellectual understanding and feminized friendship. The importance on female communities is an exhortation for women to realize their dignity and become politically autonomous individuals. This is reflective of Laura Cereta's idea of the 'Republic of Women'.[21] The women in the dialog never come to a conclusion, there is no point that is made: the space to speak freely is temporary and borrowed. The women in the end have to leave the garden to return home.[22] The garden setting displays the potential feminized society as all of Fonte's characters express the moral capacity of women and their deserving of material means to be autonomous, though from different arguments.[23]

Moderata was a transgressive and early modern author, that influenced modern thinking and understanding of feminism in historical context. Her manuscript was published after her death, as she finished completing her writings on the day before she died giving birth to her fourth child. The themes of Moderata Fonte's works are literary spaces of reevaluation. One of the larger themes are love, freedom of speech and the worth of women.[24] Some authors have suggested that Moderata Fonte's last work, along with other contemporaries like Lucrezia Marinella, were meant to be a critic against Giuseppe Passi's, I donneschi difetti [Women's Defects].[21]

Legacy and influence

Before the publications of Moderata Fonte's and Lucrezia Marinella's works, men were the only authors of writings in defense of women, with the exception of Laura Cereta's letters, which circulated as a manuscript from 1488 to 1492 among humanists in Brescia, Verona, and Venice.[25] Their personality greatly influenced the creation of the character of Isabella in the Pazzia di Isabella, by Isabella Andreini and her husband Francesco, who revitalized the querelles des femmes through the vernacular performances of the commedia dell'arte.[21] The protofeminist perspective that is developed in these literary works highlights the role of property in the devaluation of women. More recently, women have been achieving political freedom by managing their property personally.[23]

The rediscovery of her work in the 20th century is due to scholar women from Italy and America such as Eleonora Carinci,[26] Adriana Chemello,[27] Marina Zancan and Virginia Cox.[28] According to Virginia Cox and Valeria Finucci, Fonte argues that gendered differences are nurtured and cultural, rather than inherent to female biology. Patricia Labalme and Virginia Cox highlight the emergence of an early feminist critique of misogyny in the writings of these Venetian women. Diana Robin exposes the role of women in intellectual life and the historical importance of women writers. She exposes the integrated role of men, women and their relationships in this movement of recognizing the woman as an intellectual.Fonte became very cited in other works of commentary on women including Pietro Paolo di Ribera and Cristofano Bronzini.[21] More recently, English and American theoreticians took inspiration from her ideas and formulated some concepts (man's punishment, mansplaining) that are vital in current feminism.

Further reading

- Malpezzi Price, Paola (2003). Moderata Fonte: Women and Life in Sixteenth-century Venice. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

- Rinaldina Russell (editor) (1994), Italian Women Writers: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook, pp. 128–137 by Paola Malpezzi Price

References

- ↑ Fonte, Moderata (1997). The Worth of Women : Wherein is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Their Superiority to Men. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press. p. 33. ISBN 0-226-25681-2.

- ↑ Fonte, Moderata (1997). The Worth of Women : Wherein is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Their Superiority to Men. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-226-25681-2.

- ↑ "On Moderata Fonte's Feminist Reimagining of 16th-Century Venice". Literary Hub. 27 March 2018.

- ↑ Paola Malpezzi Price, "Pozzo, Modesto," Mary Hays, Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women, of All Ages and Countries (1803). Chawton House Library Series: Women's Memoirs, ed. Gina Luria Walker, Memoirs of Women Writers Part II (Pickering & Chatto: London, 2013), vol. 10, 79-80, editorial notes, 571.

- 1 2 Spencer, Anna Garlin in Kennerley, Mitchell (ed.) (1912). "The Drama of the Woman of Genius". The Forum. New York: Forum Pub. Co. 47: 41.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Cox, Virginia.Fonte, Moderata (1555-1592), Italian women writers, University of Chicago library, 2004.

- ↑ Doglioni, Giovanni Niccolo (1997), "Life of Moderata Fonte", in Fonte, Moderata (ed.), The worth of women: wherein is clearly revealed their nobility and their superiority to men, The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe, Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, pp. 31–42, ISBN 9780226256825. Preview.

- ↑ Paola Malpezzi Price. Moderata Fonte: Women and Life in Sixteenth-century Venice (Madison (N.J.): Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2003), 28.

- 1 2 Malpezzi Price, "Pozzo, Modesto," vol. 10, 79-80, editorial notes, 571; and Malpezzi Price. Moderata Fonte, 149.

- ↑ Malpezzi Price, Paola, 1948- ... (2003). Moderata Fonte : women and life in sixteenth-century Venice. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 0838639984. OCLC 469346548.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 "Biography: Fonte, Moderata". www.lib.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ↑ "Biography: Fonte, Moderata". www.lib.uchicago.edu.

- ↑ Weaver, Elissa (1997). "Tredici canti del Floridoro (review)". MLN. 112 (1): 114–116. doi:10.1353/mln.1997.0004. ISSN 1080-6598. S2CID 162082118.

- 1 2 Malpezzi Price, Paola. Moderata Fonte : Women and Life In Sixteenth-century Venice.Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2003, 33.

- ↑ Russell, Rinaldina. (1994). Italian women writers : a bio-bibliographical sourcebook. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313283478. OCLC 925190535.

- ↑ Malpezzi Price, Paola. Moderata Fonte : Women and Life In Sixteenth-century Venice.Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2003, 35.

- ↑ "On Moderata Fonte's Feminist Reimagining of 16th-Century Venice". Literary Hub. 27 March 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ↑ G. Doglioni, ‘Vita della Sig.ra Modesta Pozzo de Zorzi nominata Moderata Fonte descritta da Gio’, in M. Fonte, Il merito delle Donne, ed. Adriana Chemello (Venice: Eidos, 1988), pp. 3–10.

- ↑ The Worth of Women: Wherein is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Their Superiority to Men By Moderata Fonte (1997) translated by Virginia Cox. OCLC 44959387.

- ↑ D'Alessandro Behr, Francesca (2018). Arms and the Woman: Classical Tradition and Women Writers in the Venetian Renaissance. The Ohio State University Press. doi:10.26818/9780814213711. hdl:1811/85752. ISBN 9780814213711.

- 1 2 3 4 Ross, Sarah Gwyneth, 1975- (2009). The birth of feminism : woman as intellect in renaissance Italy and England. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03454-9. OCLC 517501929.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Jansen, Sharon L. (2011). Reading Women's Worlds from Christine de Pizan to Doris Lessing A Guide to Six Centuries of Women Writers Imagining Rooms of Their Own. Palgrave Macmillan US. ISBN 9780230118812. OCLC 1105494527.

- 1 2 Jordan, Constance. (1990). Renaissance feminism : literary texts and political models. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-2163-2. OCLC 803523255.

- ↑ D'Alessandro Behr, Francesca (2018). Arms and the woman : classical tradition and women writers in the Venetian Renaissance. Columbus. ISBN 978-0-8142-1371-1. OCLC 1002681128.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Laura Cereta: Collected Letters of a Renaissance Feminist. Transcribed, translated, and edited by Diana Robin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997, p.6

- ↑ Carinci. Eleonora. 2002. 'Una lettera autografa inedita di Moderata Fonte (al granduca di Toscana Francesco I)'. Critica del testo, 5/3: 1-11

- ↑ Chemello, Adriana. 1983. 'La donna, il modello, l'immaginario. Moderata Fonte and Lucrezia Marinella'. In Nel cerchio della luna: figure di donna in alcuni testi del XVI secolo, 95-170. Ed Marina Zancan. Venice: Marsilio

- ↑ Cox, Virginia. 1995. 'The single self: Feminist thought and the marriage market in early modern Venice'. Renaissance Quarterly, 48 (1995), 513-81

External links

- Querelle | Moderata Fonte Querelle.ca is a website devoted to the works of authors contributing to the pro-woman side of the querelle des femmes.

- it:s:Autore:Modesta Pozzo

- Project Continua: Biography of Modesto Pozzo -pseudonym Moderata Fonte Project Continua is a web-based multimedia resource dedicated to the creation and preservation of women's intellectual history from the earliest surviving evidence into the 21st century.