In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of taxa which meets these criteria:

- the grouping contains its own most recent common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population), i.e. excludes non-descendants of that common ancestor

- the grouping contains all the descendants of that common ancestor, without exception

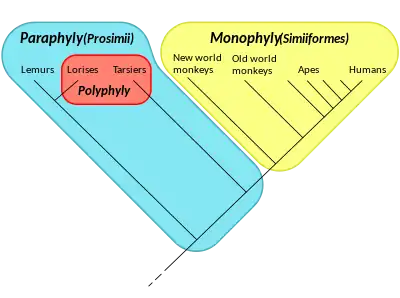

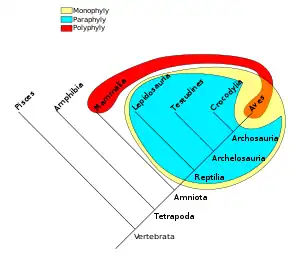

Monophyly is contrasted with paraphyly and polyphyly as shown in the second diagram. A paraphyletic grouping meets 1. but not 2., thus consisting of the descendants of a common ancestor excepting one or more monophyletic subgroups. A polyphyletic grouping meets neither criterion, and instead serves to characterize convergent relationships of biological features rather than genetic relationships – for example, night-active primates, fruit trees, or aquatic insects. As such, these characteristic features of a polyphyletic grouping are not inherited from a common ancestor, but evolved independently.

Monophyletic groups are typically characterised by shared derived characteristics (synapomorphies), which distinguish organisms in the clade from other organisms. An equivalent term is holophyly.[1]

The word "mono-phyly" means "one-tribe" in Greek.

These definitions have taken some time to be accepted. When the cladistics school of thought became mainstream in the 1960s, several alternative definitions were in use. Indeed, taxonomists sometimes used terms without defining them, leading to confusion in the early literature,[2] a confusion which persists.[3]

The first diagram shows a phylogenetic tree with two monophyletic groups. The several groups and subgroups are particularly situated as branches of the tree to indicate ordered lineal relationships between all the organisms shown. Further, any group may (or may not) be considered a taxon by modern systematics, depending upon the selection of its members in relation to their common ancestor(s); see second and third diagrams.

Etymology

The term monophyly, or monophyletic, derives from the two Ancient Greek words μόνος (mónos), meaning "alone, only, unique", and φῦλον (phûlon), meaning "genus, species",[4][5] and refers to the fact that a monophyletic group includes organisms (e.g., genera, species) consisting of all the descendants of a unique common ancestor.

Conversely, the term polyphyly, or polyphyletic, builds on the ancient Greek prefix πολύς (polús), meaning "many, a lot of",[4][5] and refers to the fact that a polyphyletic group includes organisms arising from multiple ancestral sources.

By comparison, the term paraphyly, or paraphyletic, uses the ancient Greek prefix παρά (pará), meaning "beside, near",[4][5] and refers to the situation in which one or several monophyletic subgroups are left apart from all other descendants of a unique common ancestor. That is, a paraphyletic group is nearly monophyletic, hence the prefix pará.

Definitions

On the broadest scale, definitions fall into two groups.

- Willi Hennig (1966:148) defined monophyly as groups based on synapomorphy (in contrast to paraphyletic groups, based on symplesiomorphy, and polyphyletic groups, based on convergence). Some authors have sought to define monophyly to include paraphyly as any two or more groups sharing a common ancestor.[3][6][7][8] However, this broader definition encompasses both monophyletic and paraphyletic groups as defined above. Therefore, most scientists today restrict the term "monophyletic" to refer to groups consisting of all the descendants of one (hypothetical) common ancestor.[2] However, when considering taxonomic groups such as genera and species, the most appropriate nature of their common ancestor is unclear. Assuming that it would be one individual or mating pair is unrealistic for sexually reproducing species, which are by definition interbreeding populations.[9]

- Monophyly (or holophyly) and associated terms are restricted to discussions of taxa, and are not necessarily accurate when used to describe what Hennig called tokogenetic relationships – now referred to as genealogies. Some argue that using a broader definition, such as a species and all its descendants, does not really work to define a genus.[9] The loose definition also fails to recognize the relations of all organisms.[10] According to D. M. Stamos, a satisfactory cladistic definition of a species or genus is impossible because many species (and even genera) may form by "budding" from an existing species, leaving the parent species paraphyletic; or the species or genera may be the result of hybrid speciation.[11]

The concepts of monophyly, paraphyly, and polyphyly have been used in deducing key genes for barcoding of diverse group of species.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ Allaby, Michael (2015). A Dictionary of Ecology (5 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191793158.

- 1 2 Hennig, Willi (1999) [1966]. Phylogenetic Systematics. Translated by Davis, D.; Zangerl, R. (Illinois Reissue ed.). Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. pp. 72–77. ISBN 978-0-252-06814-0.

- 1 2 Aubert, D. 2015. A formal analysis of phylogenetic terminology: Towards a reconsideration of the current paradigm in systematics. Phytoneuron 2015-66:1–54.

- 1 2 3 Bailly, Anatole (1 January 1981). Abrégé du dictionnaire grec français. Paris: Hachette. ISBN 978-2010035289. OCLC 461974285.

- 1 2 3 Bailly, Anatole. "Greek-french dictionary online". www.tabularium.be. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ↑ Colless, Donald H. (March 1972). "Monophyly". Systematic Zoology. 21 (1): 126–128. doi:10.2307/2412266. JSTOR 2412266.

- ↑ Envall, Mats (2008). "On the difference between mono-, holo-, and paraphyletic groups: a consistent distinction of process and pattern". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 94: 217–220. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.00984.x.

- ↑ Ashlock, Peter D. (March 1971). "Monophyly and Associated Terms". Systematic Zoology. 20 (1): 63–69. doi:10.2307/2412223. JSTOR 2412223.

- 1 2 Simpson, George (1961). Principles of Animal Taxonomy. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-02427-3.

- ↑ Carr, Steven M. "Monophyletic, Polyphyletic, & Paraphyletc Taxa". www.mun.ca. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ↑ Stamos, D.N. (2003). The species problem : biological species, ontology, and the metaphysics of biology. Lanham, Md. [u.a.]: Lexington Books. pp. 261–268. ISBN 978-0739105030.

- ↑ Parhi J., Tripathy P.S., Priyadarshi, H., Mandal S.C., Pandey P.K. (2019). "Diagnosis of mitogenome for robust phylogeny: A case of Cypriniformes fish group". Gene. 713: 143967. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2019.143967. PMID 31279710. S2CID 195828782.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Abbey, Darren (1994–2006). "Graphical explanation of basic phylogenetic terms". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- Carr, Steven M. (2002). "Concepts of monophyly, polyphyly & paraphyly". Memorial University. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- Hyvönen, Jaako (2005). "Monophyly, consensus, compromise" (PDF). University of Helsinki. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- "Phylogenetic Trees and Classification". Digital Atlas of Ancient Life. Paleontological Research Institution.