The word decadence, which at first meant simply "decline" in an abstract sense, is now most often used to refer to a perceived decay in standards, morals, dignity, religious faith, honour, discipline, or skill at governing among the members of the elite of a very large social structure, such as an empire or nation state. By extension, it may refer to a decline in art, literature, science, technology, and work ethics, or (very loosely) to self-indulgent behavior.

Usage of the term sometimes implies moral censure, or an acceptance of the idea, met with throughout the world since ancient times, that such declines are objectively observable and that they inevitably precede the destruction of the society in question; for this reason, modern historians use it with caution. The word originated in Medieval Latin (dēcadentia), appeared in 16th-century French, and entered English soon afterwards. It bore the neutral meaning of decay, decrease, or decline until the late 19th century, when the influence of new theories of social degeneration contributed to its modern meaning.

The idea that a society or institution is declining is called declinism. This is the predisposition, caused by cognitive biases such as rosy retrospection, to view the past more favourably and future more negatively.[1][2][3] Declinism has been described as "a trick of the mind" and as "an emotional strategy, something comforting to snuggle up to when the present day seems intolerably bleak."[4] Other factors contributing to declinism include the reminiscence bump as well as both the positivity effect and negativity bias.[2][4][5]

In literature, the Decadent movement—late nineteenth century fin de siècle writers who were associated with Symbolism or the Aesthetic movement—was first given its name by hostile critics. Later it was triumphantly adopted by some of the writers themselves. The Decadents praised artifice over nature and sophistication over simplicity, defying contemporary discourses of decline by embracing subjects and styles that their critics considered morbid and over-refined. Some of these writers were influenced by the tradition of the Gothic novel and by the poetry and fiction of Edgar Allan Poe.

History

Ancient Rome

Decadence is a popular criticism of the culture of the later Roman Empire's elites, seen also in much of its earlier historiography and 19th and early 20th century art depicting Roman life. This criticism describes the later Roman Empire as reveling in luxury, in its extreme characterized by corrupting "extravagance, weakness, and sexual deviance", as well as "orgies and sensual excesses".[6][7][8][9][10]

Decadent movement

Decadence was the name given to a number of late nineteenth-century writers who valued artifice over the earlier Romantics' naïve view of nature. Some of them triumphantly adopted the name, referring to themselves as Decadents. For the most part, they were influenced by the tradition of the Gothic novel and by the poetry and fiction of Edgar Allan Poe, and were associated with Symbolism and/or Aestheticism.

This concept of decadence dates from the eighteenth century, especially from Montesquieu and Wilmot.[11] It was taken up by critics as a term of abuse after Désiré Nisard used it against Victor Hugo and Romanticism in general. A later generation of Romantics, such as Théophile Gautier and Charles Baudelaire took the word as a badge of pride, as a sign of their rejection of what they saw as banal "progress." In the 1880s, a group of French writers referred to themselves as Decadents. The classic novel from this group is Joris-Karl Huysmans' Against Nature, often seen as the first great decadent work, though others attribute this honor to Baudelaire's works.

In Britain and Ireland the leading figure associated with the Decadent movement was Irish writer, Oscar Wilde. Other significant figures include Arthur Symons, Aubrey Beardsley and Ernest Dowson.

The Symbolist movement has frequently been confused with the Decadent movement. Several young writers were derisively referred to in the press as "decadent" in the mid-1880s. Jean Moréas' manifesto was largely a response to this polemic. A few of these writers embraced the term while most avoided it. Although the aesthetics of Symbolism and Decadence can be seen as overlapping in some areas, the two remain distinct.

1920s Berlin

This "fertile culture" of Berlin extended onwards until Adolf Hitler rose to power in early 1933 and stamped out any and all resistance to the Nazi Party. Likewise, the German far-right decried Berlin as a haven of degeneracy. A new culture had developed in and around Berlin throughout the previous decade, including architecture and design (Bauhaus, 1919–33), a variety of literature (Döblin, Berlin Alexanderplatz, 1929), film (Lang, Metropolis, 1927, Dietrich, Der blaue Engel, 1930), painting (Grosz), and music (Brecht and Weill, The Threepenny Opera, 1928), criticism (Benjamin), philosophy/psychology (Jung), and fashion. This culture was considered decadent and disruptive by rightists.[12]

Film was making huge technical and artistic strides during this period of time in Berlin, and gave rise to the influential movement called German Expressionism. "Talkies", the Sound films, were also becoming more popular with the general public across Europe, and Berlin was producing very many of them.

Berlin in the 1920s also proved to be a haven for English-language writers such as W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender and Christopher Isherwood, who wrote a series of 'Berlin novels', inspiring the play I Am a Camera, which was later adapted into a musical, Cabaret, and an Academy Award winning film of the same name. Spender's semi-autobiographical novel The Temple evokes the attitude and atmosphere of the place at the time.

Modern-day perspectives

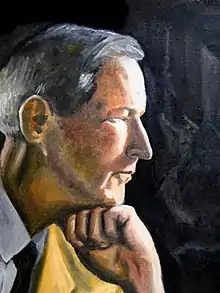

Jacques Barzun

The historian Jacques Barzun (1907-2012) gives a definition of decadence which is independent from moral judgement. In his bestseller From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life[13] (published 2000) he describes decadent eras as times when "the forms of art as of life seem exhausted, the stages of development have been run through. Institutions function painfully." He emphasizes that "decadent" in his view is "not a slur" but "a technical label".

With reference to Barzun, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat characterises decadence as a state of "economic stagnation, institutional decay and cultural and intellectual exhaustion at a high level of material prosperity and technological development".[14] Douthat sees the West in the 21st century in an "age of decadence", marked by stalemate and stagnation. He is the author of the book The Decadent Society, published by Simon & Schuster in 2020. According to the news website Vox, "Douthat’s definition of a 'decadent society' is that we’re trapped in a stale system that keeps spinning in place, reproducing the same arguments and frustrations over and over again."[15]

Pria Viswalingam

Pria Viswalingam, an Australian documentary and film maker, sees the western world in decay since the late 1960s. Viswalingam is the author of the six-episode documentary TV series Decadence: The Meaninglessness of Modern Life, broadcast in 2006 and 2007, and the 2011 documentary film Decadence: The Decline of the Western World.

According to Viswalingam, western culture started in 1215 with the Magna Carta, continued to the Renaissance, the Reformation, the founding of America, the Enlightenment and culminated with the social revolutions of the 1960s.[16]

Since 1969, the year of the Moon landing, the My Lai massacre, the Woodstock Festival and the Altamont Free Concert, "decadence depicts the west's decline". As symptoms he names increasing suicide rates, addiction to anti-depressants, exaggerated individualism, broken families and a loss of religious faith as well as "treadmill consumption, growing income-disparity, b-grade leadership", and money as the only benchmark for value.

Use in Marxism

Leninism

According to Vladimir Lenin, capitalism had reached its highest stage and could no longer provide for the general development of society. He expected reduced vigor in economic activity and a growth in unhealthy economic phenomena, reflecting capitalism's gradually decreasing capacity to provide for social needs and preparing the ground for socialist revolution in the West. Politically, World War I proved the decadent nature of the advanced capitalist countries to Lenin, that capitalism had reached the stage where it would destroy its own prior achievements more than it would advance.[17]

One who directly opposed the idea of decadence as expressed by Lenin was José Ortega y Gasset in The Revolt of the Masses (1930). He argued that the "mass man" had the notion of material progress and scientific advance deeply inculcated to the extent that it was an expectation. He also argued that contemporary progress was opposite the true decadence of the Roman Empire.[18]

Left communism

Decadence is an important aspect of contemporary left communist theory. Similar to Lenin's use of it, left communists, coming from the Communist International themselves started in fact with a theory of decadence in the first place, yet the communist left sees the theory of decadence at the heart of Marx's method as well, expressed in famous works such as The Communist Manifesto, Grundrisse, Das Kapital but most significantly in Preface to the Critique of Political Economy.[19]

Contemporary left communist theory defends that Lenin was mistaken on his definition of imperialism (although how grave his mistake was and how much of his work on imperialism is valid varies from groups to groups) and Rosa Luxemburg to be basically correct on this question, thus accepting capitalism as a world epoch similarly to Lenin, but a world epoch from which no capitalist state can oppose or avoid being a part of. On the other hand, the theoretical framework of capitalism's decadence varies between different groups while left communist organizations like the International Communist Current hold a basically Luxemburgist analysis that makes an emphasis on the world market and its expansion, others hold views more in line with those of Vladimir Lenin, Nikolai Bukharin and most importantly Henryk Grossman and Paul Mattick with an emphasis on monopolies and the falling rate of profit.

See also

References

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary of American Political Slang edited by Grant Barrett, p. 90.

- 1 2 Etchells, Pete (January 16, 2015). "Declinism: is the world actually getting worse?". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ↑ Steven R. Quartz, The State Of The World Isn't Nearly As Bad As You Think, Edge Foundation, Inc., retrieved 2016-02-17

- 1 2 Lewis, Jemima (January 16, 2016). "Why we yearn for the good old days". The Telegraph. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ↑ Gopnik, Adam (September 12, 2011). "Decline, Fall, Rinse, Repeat". The New Yorker. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ↑ Hurst, Isobel (2019-08-22), Desmarais, Jane H.; Weir, David (eds.), "Nineteenth-Century Literary and Artistic Responses to Roman Decadence", Decadence and Literature, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 47–65, ISBN 978-1-108-42624-4, retrieved 2021-07-24

- ↑ Hoffleit, Gerald (2014), Landgraf, Diemo (ed.), "Progress and Decadence—Poststructuralism as Progressivism", Decadence in Literature and Intellectual Debate since 1945, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 67–81, doi:10.1057/9781137431028_4, ISBN 978-1-137-43102-8, retrieved 2021-07-24

- ↑ Geoffrey Farrington (1994). The Dedalus Book of Roman Decadence: Emperors of Debauchery. Dedalus. ISBN 978-1-873982-16-7.

- ↑ Patrick M. House (1996). The Psychology of Decadence: The Portrayal of Ancient Romans in Selected Works of Russian Literature of the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries. University of Wisconsin--Madison.

- ↑ Toner, Jerry (2019), Weir, David; Desmarais, Jane (eds.), "Decadence in Ancient Rome", Decadence and Literature, Cambridge Critical Concepts, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 15–29, ISBN 978-1-108-42624-4, retrieved 2021-07-24

- ↑ Hughes, G. (2015). An Encyclopedia of Swearing: The Social History of Oaths, Profanity, Foul Language, and Ethnic Slurs in the English-speaking World. Taylor & Francis. p. 626. ISBN 978-1-317-47677-1. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ↑ Kirkus UK review of Laqueur, Walter Weimar: A cultural history, 1918-1933

- ↑ Barzun, Jacques: From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life. HarperCollins, New York 2000.

- ↑ Douthat, Ross (February 7, 2020). "The Age of Decadence". New York Times. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- ↑ Illing, Sean (February 28, 2020). "The case that America's in decline". www.vox.com. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- ↑ Molitorisz, Sacha (December 2, 2011). "Society is past its use by date". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2021-05-07.

- ↑ Decadence: The Theory of Decline or the Decline of Theory? (Part I). Aufheben. Summer 1993.

- ↑ Mora, José Ferrater (1956). Ortega y Gasset: an outline of his philosophy. Bowes & Bowes. p. 18.

- ↑ Marx, Karl (1859). A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Progress Publishers.

Further reading

- Richard Gilman, Decadence: The Strange Life of an Epithet (1979). ISBN 0-374-13567-3

- Matei Calinescu, Five Faces of Modernity. ISBN 0-8223-0767-7

- Mario Praz, The Romantic Agony (1930). ISBN 0-19-281061-8

- Jacques Barzun, From Dawn to Decadence, (2000). ISBN 0-06-017586-9

- A. E. Carter, The Idea of Decadence in French Literature (1978). ISBN 0-8020-7078-7

- Michael Murray, Jacques Barzun: Portrait of a Mind (2011). ISBN 978-1-929490-41-7

.jpg.webp)