| Languages of Morocco | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official | Modern Standard Arabic and Standard Moroccan Berber |

| Vernacular | Arabic dialects (92%)[1]

Berber languages (26%)[1]

|

| Foreign | French (36%)[3] English (14%)[4] Spanish (4.5%)[5] |

| Signed | Moroccan Sign Language |

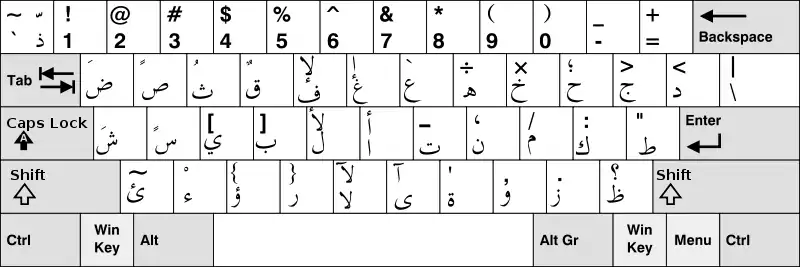

| Keyboard layout | |

There are a number of languages in Morocco. De jure, the two official languages are Standard Arabic and Standard Moroccan Berber.[6] Moroccan Arabic (known as Darija) is by far the primary spoken vernacular and lingua franca, whereas Berber languages serve as vernaculars for significant portions of the country. The languages of prestige in Morocco are Arabic in its Classical and Modern Standard Forms and sometimes French, the latter of which serves as a second language for approximately 33% of Moroccans.[7] According to a 2000–2002 survey done by Moha Ennaji, author of Multilingualism, Cultural Identity, and Education in Morocco, "there is a general agreement that Standard Arabic, Moroccan Arabic, and Berber are the national languages."[8] Ennaji also concluded "This survey confirms the idea that multilingualism in Morocco is a vivid sociolinguistic phenomenon, which is favored by many people."[9]

There are around 6 million Berber speakers in Morocco.[1] French retains a major place in Morocco, as it is taught universally and serves as Morocco's primary language of commerce and economics, culture, sciences and medicine; it is also widely used in education and government. Morocco is a member of the Francophonie.[10]

Spanish is spoken by many Moroccans, particularly in the northern regions around Tetouan and Tangier, as well as in parts of the south, due to historic ties and business interactions with Spain.[11]

According to a 2012 study by the Government of Spain, 98% of Moroccans spoke Moroccan Arabic, 63% spoke French, 26% Berber, 14% spoke English, and 10% spoke Spanish.[11]

History

Historically, languages such as Phoenician,[12] Punic,[13] and Amazigh languages have been spoken in Morocco. Juba II, king of Mauretania, wrote in Greek and Latin.[14] It is unclear how long African Romance was spoken, but its influence on Northwest African Arabic (particularly in the language of northwestern Morocco) indicates it must have had a significant presence in the early years after the Arab conquest.[15][16]

Arabic came with the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb;[17] Abdellah Guennoun cites the Friday sermon delivered by Tariq Ibn Ziad just before the conquest of al-Andalus in 711 as the first instance of Moroccan literature in Arabic.[18] However, the language spread much more slowly than the religion.[17] At first, Arabic was used only in urban areas, especially in cities in the north, while the rural areas remained the domain of Amazigh languages.[17]

Under the Almohads, the khuṭbas (from خطبة, the Friday sermon) had to be delivered in Arabic and Berber, or as the Andalusi historian Ibn Ṣāḥib aṣ-Ṣalāt described it: "al-lisān al-gharbī" (اللسان الغربي 'the western tongue').[19] The khaṭīb, or sermon-giver, of al-Qarawiyyīn Mosque in Fes, Mahdī b. ‘Īsā, was replaced under the Almohads by Abū l-Ḥasan b. ‘Aṭiyya khaṭīb because the latter was fluent in Berber.[19]

The first recorded work in Darija or Moroccan Arabic is Al-Kafif az-Zarhuni's epic zajal poem "al-Mala'ba," dating back to the reign of Marinid Sultan Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn Othman.[20]

During the Middle ages, sailors and traders in the Mediterranean, including the Barbary Coast, developed a contact language known as Mediterranean Lingua Franca or sabir. It was influenced by the languages of Italy, Catalan, Occitan, Berber, Arabic, Spanish and Portuguese. Its use declined after the European conquest.

Language policy

After Morocco gained independence with the end of the French Protectorate in 1956, it started a process of Arabization. For this task, the Institute for Studies and Research on Arabization was established by decree in 1960.[21][22] The policy of Arabization was not applied in earnest until 17 years after independence.[23] An editorial in Lamalif in 1973 argued that, although French unified the elite and major sections of the economy, national unity could only be achieved based on Arabic—though Lamalif called for a new incarnation of the language, describing Standard Arabic as untenably prescriptive and Moroccan vernacular Arabic (Darija) as too poor to become in and of itself a language of culture and knowledge.[23]

In the year 2000, after years of neglecting and ignoring the other languages present in Morocco, the Charter for Educational Reform recognized them and the necessity for them.[24]

Until then the Berber languages were marginalized in the modern society and the number of monolingual speakers decreased. In recent years, the Berber culture has been gaining strength and some developments promise that these languages will not die (Berber is the generic name for the Berber languages. The term Berber is not used nor known by the speakers of these languages).[25]

Arabic, on the other hand, has been perceived as a prestigious language in Morocco for over a millennium. However, there are very distinctive varieties of Arabic used, not all equally prestigious, which are MSA (Modern Standard Arabic), the written form used in schools and 'Dialectal Arabic', the non-standardized spoken form. The difference between the two forms in terms of grammar, phonology and vocabulary is so great, it can be considered as diglossia. MSA is practically foreign to Moroccan schoolchildren, and this creates problems with reading and writing, consequently leading to a high level of illiteracy in Morocco.[25]

The French language is also dominant in Morocco, especially in education and administration, therefore was initially learned by an elite and later on was learned by a great number of Moroccans for use in domains such as finance, science, technology and media. That is despite the government decision to implement a language policy of ignoring French after gaining independence, for the sake of creating a monolingual country.[25]

From its independence until the year 2000, Morocco opted for Arabization as a policy, in an attempt of replacing French with Arabic. By the end of the 1980s, Arabic was the dominant language in education, although French was still in use in many important domains. The goals of Arabization were not met, in linguistic terms, therefore a change was needed.[25] By 2020, the country ended its policy of Arabization, with French reimplemented as the medium of instruction in core subjects such as science and math.[26]

In 2000 the Charter of Educational Reform introduced a drastic change in language policy. From then on, Morocco has adopted a clear perpetual educational language policy with three main cores: improving and reinforcing the teaching of Arabic, using a variety of languages, such as English and French in teaching the fields of technology and science and acceptance of Berber. The state of Morocco still sees Arabic (MSA) as its national language, but acknowledges that not all Moroccans are Arabic speakers and that Arabization did not succeed in the area of science and technology. The aims of the charter seem to have been met faster than expected, probably since the conditions of the charter started to be implemented immediately. Nowadays the different minority languages are acknowledged in Morocco although Arabic still is the dominant one and is being promoted by the government.[25][27]

Amazigh was made an official language in 2011. In 2019, a law was enacted to implement the constitutional changes from 2011.[28] In particular, Amazigh was extended to all public services. Moroccan citizens can get their marriage certificates, identity cards, passports, and driver's licenses in Amazigh and the language can be used in courts. The government aims to generalize Amazigh education to all Moroccan schools.[29] However, as of 2023, only 10% of Moroccan pupils study Amazigh.[28] The government hired civil servants able to speak the three main dialects (Tachalhit, Tamazight and Tarifet) to help citizens in courts, hospitals, and other public services.[30][31]

Education

Framework Law 17:51 allowed scientific subjects to be taught in foreign languages—especially French—in public elementary schools.[32]

In 2019, the Parliament voted to expand Amazigh classes to all Moroccan schools.[33][34][35] According to Prime Minister Aziz Akhannouch, about 2,000 schools taught Amazigh in 2022 and the government was training more teachers to accelerate the roll out of Amazigh teaching.[36] As of 2023, this reform is still in progress.[37]

In July 2023, the gradual generalization of learning English from secondary school was decided by the Ministry of Education.[38]

Arabic

Arabic, along with Berber, is one of Morocco's two official languages,[6] although it is the Moroccan dialect of Arabic, namely Darija, meaning "everyday/colloquial language";[39] that is spoken or understood, frequently as a second language, by the majority of the population (about 85% of the total population). Many native Berber speakers also speak the local Arabic variant as a second language.[40] Arabic in its Classical and Standard forms is one of the two prestige languages in Morocco. Aleya Rouchdy, editor of Language Contact and Language Conflict in Arabic, said that Classical/Modern Arabic and French are constantly in conflict with one another, but that most Moroccans believe that the bilingualism of Classical Arabic and French is the most optimal choice to allow for Morocco's development.[41]

In 1995 the number of native Arabic speakers in Morocco was approximately 18.8 million (65% of the total population), and 21 million including the Moroccan diaspora.[42]

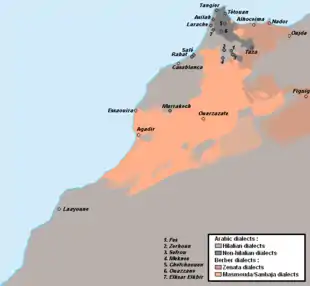

As a member of the Maghrebi Arabic grouping of dialects, Moroccan Arabic is similar to the dialects spoken in Mauritania, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya (and also Maltese). The so called Darija dialect of Morocco is quite different from its Middle Eastern counterparts but in general understandable to each other, it’s estimated that Darija shares 70/75% of its vocabulary with Modern Standard Arabic. The country shows a marked difference in urban and rural dialects. This is due to the history of settlement. traditionally, Arabs established centers of power in only a few cities and ports in the region, with the effect that the other areas remained Berber-speaking. Then, in the 13th century, Bedouin tribes swept through many of the unsettled areas, spreading with them their distinct Arabic dialect in the non-urbanized areas and leaving speakers of Berber isolated in the mountainous regions.

Modern Standard and Classical Arabic

Moroccans learn Standard Arabic as a language. It is generally not spoken at home or on the streets. Standard Arabic is frequently used in administrative offices, mosques, and schools.[43] According to Rouchdy, within Morocco Classical Arabic is still only used in literary and cultural aspects, formal traditional speeches, and discussions about religion.[41]

Dialectal Arabic

Moroccan Arabic

Moroccan Arabic, along with Berber, is one of two mother tongues acquired by Moroccan children and spoken in homes and on the street.[43] The language is not used in writing.[44] Abdelâli Bentahila, the author of the 1983 book Language Attitudes among Arabic–French Bilinguals in Morocco, said that Moroccans who were bilingual in both French and Arabic preferred to speak Arabic while discussing religion; while discussing matters in a grocery store or restaurant; and while discussing matters with family members, beggars, and maids.[45] Moha Ennaji, author of Multilingualism, Cultural Identity, and Education in Morocco, said that Moroccan Arabic has connotations of informality, and that Moroccan Arabic tends to be used in casual conversations and spoken discourse.[46] Ennaji added that Bilingual Moroccans tend to use Moroccan Arabic while in the house.[46] Berbers generally learn Moroccan Arabic as a second language and use it as a lingua franca, since not all versions of Berber are mutually intelligible with one another.[44]

The below table presents statistical figures of speakers, based on the 2014 population census.[1] This table includes not only native speakers of Arabic, but also people who speak Arabic as a second or third language.

| Region | Moroccan Arabic | Total population | % of Moroccan Arabic

speakers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casablanca-Settat | 6,785,812 | 6,826,773 | 99.4% |

| Rabat-Salé-Kénitra | 4,511,612 | 4,552,585 | 99.1% |

| Fès-Meknès | 4,124,184 | 4,216,957 | 97.8% |

| Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima | 3,426,731 | 3,540,012 | 96.8% |

| Dakhla-Oued Ed-Dahab (See Western Sahara) | 102,049 | 114,021 | 89.5% |

| Marrakesh-Safi | 4,009,243 | 4,504,767 | 89.0% |

| Oriental | 2,028,222 | 2,302,182 | 88.1% |

| Béni Mellal-Khénifra | 2,122,957 | 2,512,375 | 84.5% |

| Laâyoune-Sakia El Hamra (See Western Sahara) | 268,509 | 340,748 | 78.8% |

| Souss-Massa | 1,881,797 | 2,657,906 | 70.8% |

| Guelmim-Oued | 264,029 | 414,489 | 63.7% |

| Drâa-Tafilalet | 1,028,434 | 1,627,269 | 63.2% |

| Morocco | 30,551,566 | 33,610,084 | 90.9% |

Hassaniya Arabic

Hassānīya, is spoken by about 0.8% of the population, mainly in the territory of Western Sahara, claimed by both Morocco and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. Communities of speakers exist elsewhere in Morocco too.

The below table presents statistical figures of speakers, based on the 2014 population census.[1]

| Region | Hassaniya Arabic | Total population | % of Hassaniya Arabic

speakers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laâyoune-Sakia El Hamra | 133,914 | 340,748 | 39.3% |

| Guelmim-Oued Noun | 86,214 | 414,489 | 20.8% |

| Dakhla-Oued Ed-Dahab | 21,322 | 114,021 | 18.7% |

| Souss-Massa | 13,290 | 2,657,906 | 0.5% |

| Drâa-Tafilalet | 3,255 | 1,627,269 | 0.2% |

| Casablanca-Settat | 6,827 | 6,826,773 | 0.1% |

| Rabat-Salé-Kénitra | 4,553 | 4,552,585 | 0.1% |

| Marrakesh-Safi | 4,505 | 4,504,767 | 0.1% |

| Béni Mellal-Khénifra | 2,512 | 2,512,375 | 0.1% |

| Fès-Meknès | 0 | 4,216,957 | 0.0% |

| Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima | 0 | 3,540,012 | 0.0% |

| Oriental | 0 | 2,302,182 | 0.0% |

| Morocco | 268,881 | 33,610,084 | 0.8% |

Berber

The exact population of speakers of Berber languages is hard to ascertain, since most North African countries do not—traditionally—record language data in their censuses (An exception to this was the 2004 Morocco population census). The Ethnologue provides a useful academic starting point; however, its bibliographic references are inadequate, and it rates its own accuracy at only B-C for the area. Early colonial censuses may provide better documented figures for some countries; however, these are also very much out of date. The number for each Berber language is difficult to estimate.

Berber serves as a vernacular language in many rural areas of Morocco.[44] Berber, along with Moroccan Arabic, is one of two languages spoken in homes and on the street.[43] The population does not use Berber in writing. Aleya Rouchdy, editor of Language Contact and Language Conflict in Arabic, said that Berber is mainly used in the contexts of family, friendship, and "street".[44] In his 2000–2002 research, Ennaji found that 52% of the interviewees placed Berber as a language inferior to Arabic because it did not have a prestigious status and because its domain was restricted.[47] Ennaji added that "[t]he dialectisation of Berber certainly reduces its power of communication and its spread."[8]

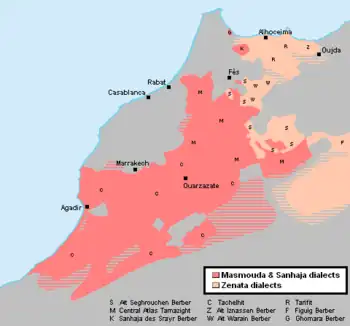

Speakers of Riffian language were estimated to be around 1.5 million in 1990.[48] The language is spoken in the Rif area in the north of the country and is one of the three main Berber languages of Morocco.

The Tashelhit language is considered to be the most widely spoken as it covers the whole of the Region Souss-Massa-Drâa, and is also spoken in the Marrakech-Tensift-El Haouz and Tadla-Azilal regions. Studies done in 1990 show around 3 million people, concentrated in the south of Morocco, speak the language.[48]

Central Morocco Tamazight is the second Berber language in Morocco. A 1998 study done by Ethnologue, shows that around 3 million people speak the language in Morocco.[49] The language is most used in the regions Middle Atlas, High Atlas and east High Atlas Mountains.

Other Berber languages are spoken in Morocco, as the Senhaja de Srair and the Ghomara dialects in the Rif mountains, the Figuig Shilha (not to be confused with Atlas Shilha) and Eastern Zenati in eastern Morocco, and Eastern Middle Atlas dialects in central Morocco.

2014 population census

Local used languages in Morocco:[1]

| Local used languages | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Darija | 92.2% | 89.7% | 90.9% |

| Tashelhit | 14.2% | 14.1% | 14.1% |

| Tamazight | 7.9% | 8.0% | 7.9% |

| Tarifit | 4.0% | 4.1% | 4.0% |

| Hassania | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.8% |

2014 population census by region

The below table presents statistical figures of speakers of Berber languages, based on the 2014 population census.[1]

| Region | Tashelhit | Tamazight | Tarifit | % of Berber speakers | Number of Berber speakers | Total population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drâa-Tafilalet | 22.0% | 48.5% | 0.1% | 70.6% | 1,148,852 | 1,627,269 |

| Souss-Massa | 65.9% | 1.1% | 0.1% | 67.1% | 1,783,455 | 2,657,906 |

| Guelmim-Oued Noun | 52.0% | 1.3% | 0.2% | 53.5% | 221,752 | 414,489 |

| Oriental | 2.9% | 6.5% | 36.5% | 45.9% | 1,056,702 | 2,302,182 |

| Béni Mellal-Khénifra | 10.6% | 30.2% | 0.1% | 40.9% | 1,027,561 | 2,512,375 |

| Marrakesh-Safi | 26.3% | 0.5% | 0.1% | 26.9% | 1,211,782 | 4,504,767 |

| Dakhla-Oued Ed-Dahab | 17.9% | 4.6% | 0.4% | 22.9% | 26,110 | 114,021 |

| Fès-Meknès | 1.9% | 12.9% | 2.4% | 17.2% | 725,317 | 4,216,957 |

| Laâyoune-Sakia El Hamra | 12.8% | 2.7% | 0.3% | 15.8% | 53,838 | 340,748 |

| Tangier-Tetouan-Alhoceima | 1.7% | 0.6% | 10.3% | 12.6% | 446,041 | 3,540,012 |

| Rabat-Salé-Kénitra | 5.2% | 6.3% | 0.4% | 11.9% | 541,758 | 4,552,585 |

| Casablanca-Settat | 6.9% | 0.7% | 0.2% | 7.8% | 532,488 | 6,826,773 |

| Morocco | 14.1% | 7.9% | 4.0% | 26.0% | 8,738,622 | 33,610,084 |

Other studies

"Few census figures are available; all countries (Algeria and Morocco included) do not count Berber languages. Population shifts in location and number, effects of urbanization and education in other languages, etc., make estimates difficult. In 1952 A. Basset (LLB.4) estimated the number of Berberophones at 5,500,000. Between 1968 and 1978 estimates ranged from eight to thirteen million (as reported by Galand, LELB 56, pp. 107, 123–25); Voegelin and Voegelin (1977, p. 297) call eight million a conservative estimate. In 1980, S. Chaker estimated that the Berberophone populations of Kabylie and the three Moroccan groups numbered more than one million each; and that in Algeria, 3,650,000, or one out of five Algerians, speak a Berber language (Chaker 1984, pp. 8-)

In 1952, André Basset ("La langue berbère", Handbook of African Languages, Part I, Oxford) estimated that a "small majority" of Morocco's population spoke Berber. The 1960 census estimated that 34% of Moroccans spoke Berber, including bi-, tri-, and quadrilinguals. In 2000, Karl Prasse cited "more than half" in an interview conducted by Brahim Karada at Tawalt.com. According to the Ethnologue (by deduction from its Moroccan Arabic figures), the Berber-speaking population is estimated at 65% (1991 and 1995). However, the figures it gives for individual languages only add up to 7.5 million, or about 57%. Most of these are accounted for by three dialects:

- Riff: 4.5 million (1991)

- Shilha: 7 million (1998)

- Central Morocco Tamazight: 7 million (1998)

This nomenclature is common in linguistic publications, but is significantly complicated by local usage: thus Shilha is sub-divided into Shilha of the Dra valley, Tasusit (the language of the Souss) and several other (mountain) dialects. Moreover, linguistic boundaries are blurred, such that certain dialects cannot accurately be described as either Central Morocco Tamazight (spoken in the Central and eastern Atlas area) or Shilha. The differences among all Moroccan dialects are not too pronounced: public radio news are broadcast using the various dialects; each journalist speaks his or her own dialect with the result that understanding is not obstructed, though most southern Berbers find that understanding Riff requires some getting used to.

French

Within Morocco, French, one of the country's two prestige languages,[41] is often used for business, diplomacy, and government;[50] and serves as a lingua franca.[51] Aleya Rouchdy, editor of Language Contact and Language Conflict in Arabic, said that "For all practical purposes, French is used as a second language."[44]

Different figures of French speakers in Morocco are given. According to the OIF, 36% of Moroccans speak French overall, while 47% of students have French as their medium of instruction at schools.[3] According to the 2014 census, about 66% of literate people can read and write French,[52] that is, 66% of 68% = 45%. Other sources put the number of total French speakers at 64% as of 2014.[53]

Spanish

In a survey from 2005 by the CIDOB (Barcelona Centre for International Affairs), 21.9% of respondents from Morocco claimed to speak Spanish, with higher percentages in the northern regions.[54] By 2017, that figure had declined to about 4.5% of the population.[55]

Spanish was used in northern Morocco and Western Sahara due to Spanish occupation of those areas and the incorporation of Spanish Sahara as a province. After Morocco declared independence in 1956, French and Arabic became the main languages of administration and education, causing the role of Spanish to decline. In northern Morocco, transmission of Spanish television is often available and there are interactions in Spanish on a daily basis in areas bordering the Spanish cities of Ceuta and Melilla.[41]

Today, Spanish is still offered as one of the foreign languages in the educational system but has fallen well behind French and English. According to the Cervantes Institute, there were 11,409 students learning Spanish in Morocco in 2016, a large decline from about 50,000 in 2005. Demand for Spanish and overall competency in the language has fallen since the start of the 21st century.[56]

Judeo-Spanish

After the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, thousands of Sephardic Jews took refuge in Morocco. The Jews of Portugal were similarly expelled in 1496. They spoke Old Spanish, Portuguese, Judeo-Catalan, Judeo-Aragonese and other Romance languages. Mixing in Morocco and influenced by local Arabic, their language became Haketia (with an offshoot in Oran, now part of Algeria). Unlike other Judeo-Spanish dialects, Haketia did not develop a literature and, during colonization, North African Sephardim adopted Spanish and French. Emigration to Spain, Iberoamerica, and Israel has reduced the number of speakers of Haketia by a lot.

See also

References

- Ennaji, Moha. Multilingualism, Cultural Identity, and Education in Morocco. Springer Publishing, January 20, 2005. p. 127. ISBN 0387239790, 9780387239798.

- Rouchdy, Aleya. Language Contact and Language Conflict in Arabic. Psychology Press, January 6, 2003. Volume 3 of Curzon Arabic Linguistics Series, Curzon Studies in Arabic Linguistics. p. 71. ISBN 0700713794, 9780700713790.

- Stevens, Paul B. "Language Attitudes among Arabic-French Bilinguals in Morocco." (book review) Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 1985 4:73. p. 73–76. doi:10.1177/0261927X8500400107.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "2014 General Population and Habitat Census". rgphentableaux.hcp.ma. Retrieved 2019-09-15.

- ↑ "Ethnologue 14 report for Morocco". 2007-11-19. Archived from the original on 2007-11-19. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- 1 2 La langue française dans le monde, 2022." Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie. p. 31. Retrieved on 1 April 2023.

- ↑ "British Council – United Kingdom" (PDF). britishcouncil.org. May 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-13.

- ↑ Saga, Ahlam Ben. Instituto Cervantes: 1.7 Million Moroccans Speak Spanish Archived 15 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Morocco World News, 29 Nov 2018. Retrieved 11 Apr 2022.

- 1 2 2011 Constitution of Morocco Full text of the 2011 Constitution (French) Archived 2012-02-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "La Francophonie dans le monde." (Archive) Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie. p. 16. Retrieved on 15 October 2012.

- 1 2 Ennaji, p. 164.

- ↑ Ennaji, p. 162-163.

- ↑ Francophonie: 88 Etats et gouvernements

- 1 2 Fernández Vítores, David (2014), La lengua española en Marruecos (PDF), ISBN 978-9954-22-936-1, archived from the original (PDF) on November 22, 2019

- ↑ Markoe, Glenn (2000-01-01). Phoenicians. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22614-2.

- ↑ Pennell, C. R. (2013-10-01). Morocco: From Empire to Independence. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-78074-455-1.

- ↑ Elder.), Pliny (the (1857). The Natural History of Pliny. H. G. Bohn.

- ↑ Martin Haspelmath; Uri Tadmor (22 December 2009). Loanwords in the World's Languages: A Comparative Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. p. 195. ISBN 978-3-11-021844-2.

- ↑ Smaïli, Kamel (2019-10-04). Arabic Language Processing: From Theory to Practice: 7th International Conference, ICALP 2019, Nancy, France, October 16–17, 2019, Proceedings. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-32959-4.

- 1 2 3 المنصور, محمد (2017-01-02). "كيف تعرب المغرب". زمان (in Arabic). Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ↑ كنون، عبد الله (1908–1989) المؤلف (2014). النبوغ المغربي في الأدب العربي. دارالكتب العلمية،. ISBN 978-2-7451-8292-0. OCLC 949484459.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 "The Preaching of the Almohads: Loyalty and Resistance across the Strait of Gibraltar", Spanning the Strait, BRILL, pp. 71–101, 2013-01-01, doi:10.1163/9789004256644_004, ISBN 9789004256644, retrieved 2023-02-13

- ↑ "الملعبة، أقدم نص بالدارجة المغربية". 27 May 2018.

- ↑ "Décret n° 2-59-1965 du 15 rejeb 1379 (14 Janvier 1960) portant création d'un Institut d'études et de recherches pour l'arabisation". adala.justice.gov.ma. Retrieved 2021-03-31.

- ↑ Alalou, Ali (2006). "Language and Ideology in the Maghreb: Francophonie and Other Languages". The French Review. 80 (2): 408–421. ISSN 0016-111X. JSTOR 25480661.

- 1 2 "Le dossier de l'arabisation". Lamalif. 58: 14. April 1973.

- ↑ Deroche, Frédéric (2008-01-01). Les peuples autochtones et leur relation originale à la terre: un questionnement pour l'ordre mondial (in French). L'Harmattan. ISBN 9782296055858.

- 1 2 3 4 5 James Cohen; Kara T. McAlister; Kellie Rolstad; Jeff MacSwan, eds. (2005), "From Monolingualism to Multilingualism: Recent Changes in Moroccan Language Policy" (PDF), ISB4: Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism, Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press, pp. 1487–1500, retrieved 30 April 2017

- ↑ Berets, Rachel. The Latest in Language Confusion: Morocco Switches Back from Arabic to French, Al-Fanar Media, 2 March 2020.

- ↑ Marley, D. (2004). Language Attitudes in Morocco Following Recent Changes in Language Policy. Language Policy 3. Klauwer Academic Publishers. Pp. 25–46.

- 1 2 "Au Maroc, le long chemin vers la reconnaissance de l'identité amazighe". Le Monde.fr (in French). 2023-02-09. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ↑ "Le berbère enseigné dans les écoles marocaines". BBC News Afrique (in French). 2019-06-12. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ↑ ALAMI, Malak EL. "La stratégie du gouvernement pour promouvoir l'Amazigh dans l'administration publique". L'Opinion Maroc – Actualité et Infos au Maroc et dans le monde. (in French). Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ↑ "Maroc : l'Amazigh reconnue officiellement comme une langue de travail". bladinet (in French). Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ↑ "The Latest in Language Confusion: Morocco Switches Back from Arabic to French". Al-Fanar Media. 2020-03-02. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ↑ "La langue amazighe (berbère) sera enseignée dans les écoles du Maroc". Franceinfo (in French). 2019-06-13. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ↑ "Enseignement de l'amazigh : Le ministre de l'Éducation nationale dévoi". m.lematin.ma. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ↑ LesEco.ma (2021-01-14). "Enseignement : l'amazigh sera généralisé". LesEco.ma (in French). Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ↑ LEMATIN.ma. "Akhannouch: 1.941 écoles primaires ont enseigné l'amazighe en 2022". lematin.ma (in French). Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ↑ Yabiladi.com. "Maroc : Une application dédiée à l'apprentissage de l'Amazigh bientôt développée". www.yabiladi.com (in French). Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ↑ LeMonde Afrique. "MAROC Au Maroc, les jeunes préfèrent l'anglais au français". LeMonde Afrique (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-04.

- ↑ Wehr, Hans: Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic (2011); Harrell, Richard S.: Dictionary of Moroccan Arabic (1966)

- ↑ Ethnologue report for language code: shi. Ethnologue.com. Retrieved on 2011-07-23.

- 1 2 3 4 Rouchdy, Aleya, ed. (2002). Language Contact and Language Conflict in Arabic: Variations on a Sociolinguistic Theme. Psychology Press. p. 71. ISBN 0700713794.

- ↑ Ethnologue report for language code: ary. Ethnologue.com. Retrieved on 2011-07-23.

- 1 2 3 Ennaji, p. 162.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rouchdy, Aleya, ed. (2002). Language Contact and Language Conflict in Arabic: Variations on a Sociolinguistic Theme. Psychology Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-7007-1379-0.

- ↑ Stevens, p. 73.

- 1 2 Ennaji, Moha (2005). Multilingualism, Cultural Identity, and Education in Morocco. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 127. ISBN 9780387239798.

- ↑ Ennaji, p. 163.

- 1 2 Ethnologue report for language code: rif. Ethnologue.com. Retrieved on 2011-07-23.

- ↑ Ethnologue report for language code: tzm. Ethnologue.com. Retrieved on 2011-07-23.

- ↑ "Morocco", CIA World Factbook, retrieved 13 October 2012,

French (often the language of business, government, and diplomacy)

- ↑ "Bitter Fruit: where Donegal's jobs went." Irish Independent. Saturday January 16, 1999. Retrieved on October 15, 2012. "Behind the locked gates and the sign saying "Interdit au Public" (forbidden to the public) (French is the lingua franca in Morocco)"

- ↑ Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitat 2014. Présentation des premiers résultats (in French)

- ↑ English and Soft Skills in the Maghreb, p.37 British Council, 2016.

- ↑ Leyre Gil Perdomingo; Jaime Otero Roth (2008), "Enseñanza y uso de la lengua española en el Sáhara Occidental" (PDF), Analysis of the Real Instituto Elcano nº 116

- ↑ "Spanish". Ethnologue. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ Peregil, Francisco. Morocco’s diminishing interest in learning Spanish, El País, 17 Jan 2018.

Further reading

- Bentahila, Abdelâli. "Language attitudes among Arabic-French bilinguals in Morocco". Multilingual Matters (Clevedon, Avon, England), 1983. Series #4. ISBN 0585259763 (electronic book), 0585259763 (electronic book), 9780585259765 (electronic book).

- Bentahila, Abdelâli. "Motivations for Code-Switching among Arabic-French Bilinguals in Morocco." Language & Communication. 1983. Volume 3, p. 233 – 243. ISSN 0271-5309, EISSN 1873-3395, doi:10.1016/0271-5309(83)90003-4.

- Chakrani, Brahim. "A sociolinguistic investigation of language attitudes among youth in Morocco." (dissertation) ProQuest. ISBN 1124581251. UMI Number: 3452059.

- Heath, Jeffrey. "Jewish and Muslim Dialects of Moroccan Arabic". Routledge, 2013. ISBN 9781136126420 (preview)

- Keil-Sagawe, Regina. "Soziokulturelle und sprachenpolitische Aspekte der Francophonie am Beispiel Marokko (Manuskripte zur Sprachlehrforschung, 38) by Martina Butzke-Rudzynski" (review). Zeitschrift für französische Sprache und Literatur. Franz Steiner Verlag. Bd. 106, H. 3, 1996. p. 295–298. Available at JStor. The document is in the German language.

- Lahjomri, Abdeljalil. Enseignement de la langue francaise au Maroc et dialogue des cultures (Teaching of the French Language in Morocco and Dialogue of Cultures). Francais dans le Monde. 1984. p. 18–21. ERIC #: EJ312036. The document is in the French language. See profile at ERIC.

- Languages of Morocco

- Sadiqi, Fatima. Women, Gender and Language in Morocco. 01/2003, Women and Gender Ser., ISBN 9004128530, Volume 1., p. 354

- Salah-Dine Hammoud, Mohamed (1982). "Arabization in Morocco: A Case Study in Language Planning and Language Policy Attitudes." Unpublished PhD dissertation for the University of Texas at Austin, Available from University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, Michigan.