| Moselle Romance | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Germany |

| Region | Along the Moselle River near France |

| Extinct | 11th century |

Early forms | Old Latin

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

Moselle Romance (German: Moselromanisch; French: Roman de la Moselle) is an extinct Gallo-Romance (most probably Langue d'oïl) dialect that developed after the fall of the Roman Empire along the Moselle river in modern-day Germany, near the border with France. It was part of a wider group of Romance relic areas within the German-speaking territory.[2] Despite heavy Germanic influence, it persisted in isolated pockets until at least the 11th century.[3]

Historical background

After Julius Caesar conquered Gaul in 50 BC, a Gallo-Roman culture gradually developed in what is today France, southern Belgium, Luxembourg, and the region between Trier and Koblenz. By contrast, the adjacent province of Germania Inferior and part of Germania Superior retained a Germanic character throughout the Imperial period.

Emergence

According to linguist Alberto Varvaro the linguistic frontier between German and Latin populations around the 13th century was similar to the present language frontier, but only a few years before there still was a "remaining area of neolatin speakers" in the valleys of the Mosella river (near old Roman Treviri).[4]

Probably until the first 1200s some farmers around Trier spoke this Moselle Romance, according to Varvaro.

Decline

The local Gallo-Roman placenames suggest that the left bank of the Moselle was Germanized following the 8th century, but the right bank remained a Romance-speaking island into at least the 11th century.

Said names include Maring-Noviand, Osann-Monzel, Longuich, Riol, Hatzenport, Longkamp, Karden, and Kröv or Alf.

This being a wine-growing region, a number of viticultural terms from Moselle Romance have survived in the local German dialect.[3]

Evidences in the actual local Moselle dialect

In the actual and completely Germanized Mosel-Roman language island, the Gallo-Roman place names were able to survive in a particularly distinctive form: for example the place name Welschbillig indicates the former presence of the Welschen (Romanized Celts) in the entire region.

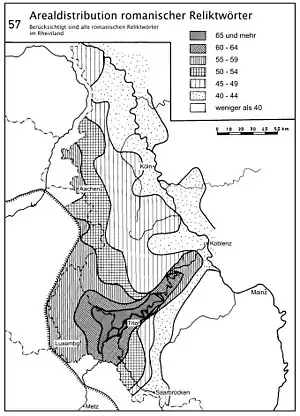

In addition to the Gallo-Roman place and field names, the vocabulary of the Moselle dialects also shows a wealth of Roman influences, which can be viewed as reflexes of the Moselle Roman language island. A quantifying cartographic representation of Romanesque relic word areas shows a clear massing of Romanisms in the middle Moselle area up to the Trier area and the lower reaches of the Saar and Sauer.[6] Examples of such words are : Bäschoff 'back container' < bascauda, Even 'oats' < avena, Fräge 'strawberry' < fraga, Gimme ' 'Bud' < gemma, glinnen 'Glean grapes' < glennare, More 'Blackberry' < morum, pauern 'Most filter ' < purare, Präter 'Flurschütz' < pratarius, Pülpes 'Crownfoot' (plant) < pulli pes etc.[7]

Features

The following Late Latin inscription from the sixth century is assumed to show influence from early Moselle Romance:

- Hoc tetolo fecet Montana, coniux sua, Mauricio, qui visit con elo annus dodece; et portavit annus qarranta; trasit die VIII K(a)l(endas) Iunias.

"For Mauricius his wife Montana who lived with him for twelve years made this gravestone; he was forty years old and died on the 25th of May."[8]

A Latin text from the 9th century written in the monastery of Prüm by local monks contains several Vulgar Latin terms which are attested only in modern Gallo-Romance languages, especially northeastern French and Franco-Provençal, such materiamen 'timber' or porritum 'chives'. Based on evidence from toponyms and loanwords into Moselle Franconian dialects, the latest detectable form of Moselle Romance can be classified as a Langue d'oïl dialect. This can be seen e.g. in the placenames Kasnode < *cassanētu and Roveroth < *roburētu, which display a characteristic change of Vulgar Latin stressed /e/ in open syllables.[9]

Lengua ignota link possibility

Scholars such as D'Ambrosio claim that the lingua ignota of SaintHildegard of Bingen may be related to the Romance language of the Moselle, although Hildegard's language appears to be an invented medieval Latin. Indeed, words from this "lingua" of Hildegard, such as "loifolum" similar to the Italian "la Folla" (that is, "the people" in English), clearly show a Neo-Latin origin.

Saint Hildegard (on her preaching trips) was in the Moselle River Valley (present-day Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany) in the last years of the proven existence of this Romance language. In fact the language disappears in the surroundings of Trier (and perhaps also in Strasbourg) during the years of life and preaching of this Saint.

See also

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (24 May 2022). "Oil". Glottolog. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ↑ Haubrichs, Wolfgang (2003). "Die verlorene Romanität im deutschen Sprachraum". In Gerhard Ernst; Martin-Dietrich Gleßgen; Christian Schmitt; Wolfgang Schweickard (eds.). Romanische Sprachgeschichte. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 695–709. ISBN 9783110194128.

- 1 2 Post, Rudolf (2004). "Zur Geschichte und Erforschung des Moselromanischen". Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter. 68: 1–35. ISSN 0035-4473.

- ↑ Alberto Varvaro."Federiciana". Treccani Enciclopedia ()

- ↑ Rudolf Post. "Romanesque borrowings in the West-Central German dialects".Editor Steiner. Wiesbaden,1982 ISBN 978-3-515-03863-8

- ↑ Post, Rudolf (1982). Romanische Entlehnungen in den westmitteldeutschen Mundarten (in German). Wiesbaden: F. Steiner. ISBN 3-515-03863-9.

- ↑ Rudolf Post, Romance Borrowings in West Central German Dialects, 1982, pp 49-261

- ↑ Johannes Kramer: Zwischen Latein und Moselromanisch. Die Gondorfer Grabinschrift für Mauricius. In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, Bd. 118 (1997) S. 281–286, ISSN 0084-5388 (PDF; 292 kB)

- ↑ Pitz, Martina (2008). "Zu Genese und Lebensdauer der romanischen Sprachinseln an Mosel und Mittelrhein". In Greule, Albrecht (ed.). Studien zu Literatur, Sprache und Geschichte in Europa: Wolfgang Haubrichs zum 65. Geburtstag gewidmet. St. Ingbert: Röhrig Universitätsverlag. pp. 439–450. ISBN 9783861104360.

Further reading

- Jungandreas, Wolfgang (1979). Zur Geschichte des Moselromanischen (in German). Wiesbaden: Rudolf Steiner Press. ISBN 978-3-515-03137-0.