A mudlark is someone who scavenges the banks and shores of rivers for items of value, a term used especially to describe those who scavenged this way in London during the late 18th and 19th centuries.[1] The practice of searching the banks of rivers for items continues in the modern era, with newer technology such as metal detectors sometimes being employed to search for metal valuables that may have washed ashore.

Mudlarks in the 18th and 19th centuries

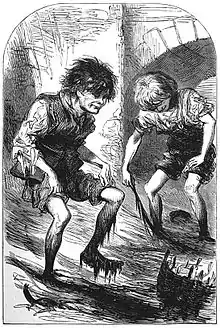

Mudlarks would search the muddy shores of the River Thames at low tide for anything that could be sold – sometimes, when occasion arose, pilfering from river traffic as well.[2] By at least the late 18th century, people dwelling near the river could scrape a subsistence living this way. Mudlarks were usually either youngsters aged between 8 and 15, or the robust elderly, and though most mudlarks were male,[3] girls and women were also scavengers.[4]

Becoming a mudlark was usually a choice dictated by poverty and lack of skills. Work conditions were filthy and uncomfortable, as excrement and waste would wash onto the shores from the raw sewage and sometimes also the corpses of humans, cats and dogs. Mudlarks would often get cuts from broken glass left on the shore. The income generated was seldom more than meagre;[4] but mudlarks had a degree of independence, since (subject to tides) the hours they worked were entirely at their own discretion and they also kept everything they made as a result of their own labour.

Henry Mayhew, in his book London Labour and the London Poor; Extra Volume, 1851, provides a detailed description of this category, and in a later edition of the same work includes the "Narrative of a Mudlark", an interview with a thirteen-year-old boy, Martin Prior.

Although in 1904 a person could still claim "mudlark" as an occupation, by then it seems to have been no longer viewed as an acceptable or lawful pursuit.[5] By 1936 the word is used merely to describe swimsuited London schoolchildren earning pocket money during the summer holidays by begging passers-by to throw coins into the Thames mud, which they then chased, to the amusement of the onlookers.[6]

Modern times

.jpg.webp)

More recently, metal-detectorists and other individuals searching the foreshore for historic artefacts have described themselves as "mudlarks". In London, a licence is required from the Port of London Authority for this activity and it is illegal to search for or remove artefacts of any kind from the foreshore without one.[7] The regulations changed in 2016, making Ted Sandling's popular book London in Fragments out of date in this respect.[8]

The PLA state that "All the foreshore in the UK has an owner. Metal detecting, searching or digging is not a public right and as such it needs the permission of the landowner. The PLA and the Crown Estate are the largest land owners of Thames foreshore and jointly administer a permit which allows metal detecting, searching or digging."[9] The PLA site has much useful information for permit holders including maps, rules & regulations about where digging is and is not permitted, safety and tide tables.

Occasionally, objects of archaeological value have been recovered from the Thames foreshore. Dependent on their value, these are either reported as treasure under the Treasure Act 1996, or voluntarily submitted for analysis and review via the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

A BBC article in July 2020 recommended the Thames Discovery Programme, "a group of historians and volunteers [running] guided tours" for novice mudlarks, and in 2019 the book Mudlarking: Lost and Found on the River Thames by Lara Maiklem was first published.[10] The author had considerable experience in searching the banks of the river for historical artefacts.[11] Rag and Bone: A Family History of What We've Thrown Away by Lisa Woollett (2020) is another examination of the subject.

Cultural references

- The word was used in the late 18th century as a slang expression for a pig.[12]

- Poor Jack, novel by Frederick Marryat, 1842. In his novel Marryat, who was himself a seaman before he turned to writing, vividly describes the unlikely rise of a fictional mudlark, Thomas Saunders, to the position of river pilot. The book contains many scenes descriptive of the typical mudlark's life, and also suggests that some adult mudlarks were involved in fencing items of cargo stolen and passed to them by crew.

- A mudlark is also a term used in Sussex dialect for a fisherman from Rye.[13]

- The Copper Treasure – a 1998 book for teenagers by Melvin Burgess describing three 19th century mudlarks and their struggle to successfully transport a roll of stolen copper.[14]

- The Mudlark – a 1950 British film about a young street boy whose contact with Queen Victoria plays a part in bringing her back to public life after her lengthy mourning for Prince Albert.

- In Neal Stephenson's The Baroque Cycle, one of the lead characters, Jack Shaftoe, begins life as a mudlark.

- In Ch146 of the manga Black Butler, Commissioner Randall calls young Mr. Pitt “a pathetic Thames mudlark”, and Mr. Pitt replies he hasn’t done that in years.

- Mudlark by John Sedden (Puffin 2005) is a thriller set in Portsmouth in the First World War in which two mudlarks find a human skull in the mud of Portsmouth Harbour, beginning a chain of tragi-comic events.

- Society of Thames Mudlarks – A modern organisation founded in 1980 which has a special licence issued by the Port of London Authority for its members to search the Thames mud for treasure and historical artefacts and report their finds to the Museum of London.[15] In 2009 one of the founder members, Tony Pilson, donated a collection of over two and a half thousand buttons dating from the 14th to the late 19th century, which he had collected along the Thames foreshore.[16]

- The television show Mud Men follows Johnny Vaughan as he teams up with Steve Brooker to go mudlarking along the Thames foreshore.

- The Faerie Ring, a book by Kiki Hamilton makes a few references to mudlarks.

- Mudlarks, a 2014 PC mystery/paranormal adventure game by Cloak and Dagger Games, features mudlarks and mudlarking prominently in the storyline.

- The term mudlark is used in the 2012 video game Dishonored by several NPCs, which reflects the games Victorian-inspired tableaux & setting.

- In the 2008 Doctor Who audio drama The Haunting of Thomas Brewster, the title character was a mudlark on the Thames in 1867.

- In Radio 4's 2020 three-part drama "London Particular" mudlarking is a key driver of the storyline.

- In season 9, episode 1 of Call The Midwife, a BBC series featuring a midwifery-focused narrative set in the 1960s in Poplar, England, an elderly character mentions that back in her youth mudlarks would occasionally recover the bodies of abandoned babies.

- In the book series The Bone Season by Samantha Shannon, Mudlarks are social outcasts who live in the sewer systems of London

See also

- Britain at Low Tide

- Beachcombing - the practice of searching beaches for items of value, interest or utility

- Grubber — someone who scavenges in drains

- Junk man

- Rag-and-bone man

- Magnet fishing — A modern method, in which a scavenger lowers a neodymium magnet into bodies of water to search for and retrieve metal items of value

- Tosher — someone who scavenges in sewers

- Waste picker

References

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary. Third edition, March 2003; online version March 2011: According to the Oxford English Dictionary, first published use of the word was in 1785 as a slang term meaning 'a hog'. The dictionary speculates its origin may have been a humorous variation on 'skylark'. By 1796 the word was also being used to describe 'Men and boys ... who prowl about, and watch under the ships when the tide will permit.'

- ↑ Henry Mayhew, London Labour and the London Poor; Extra Volume 1851: "Their practice is to get between the barges, and one of them lifting the other up will knock lumps of coal into the mud, which they pick up afterwards; or if a barge is ladened with iron, one will get into it and throw iron out to the other, and watch an opportunity to carry away the plunder in bags to the nearest marine-storeshop."

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, 1989 edition:"1796 P. COLQUHOUN, Police of Metropolis vol. iii. p.60 'Men and boys, known by the name of Mud-larks, who prowl about, and watch under the ships when the tide will permit.'"

- 1 2 Henry Mayhew, London Labour and the London Poor; Extra Volume 1861

- ↑ The Times, Friday, Mar 11, 1904; pg. 11; Issue 37339; col F, The Police Courts: a 21-year-old man, Robert Harold, "describing himself as a mudlark", was convicted and sentenced to one month in prison for unlawful possession of a length of chain he had dug out from the Thames foreshore, despite the police being unable to cite any owner for the chain.

- ↑ The Times, Friday, Sep 04, 1936; pg. 15; Issue 47471; col D "Coppers In The Mud: A Thames Pastime"

- ↑ The full current rules as of July 2018 can be found at https://www.pla.co.uk/Environment/Thames-foreshore-access-including-metal-detecting-searching-and-digging

- ↑ Ted Sandling, London in Fragments: A Mudlark's Treasures, Frances Lincoln Ltd, London 2016. ISBN 978-0-7112-3787-2. The advice given on pages 240 to 243 of the original hardback edition about foreshore searching is now out of date. This has been corrected for the 2018 paperback re-issue.

- ↑ "PLA website - permit information".

- ↑ The Lost Treasures of London's River Thames

- ↑ How to Scavenge for Bits of History Like London’s Mudlarks

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, 1989 edition: 1785 F. GROSE, Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, 'Mud lark, a hog'".

- ↑ Arscott 2006

- ↑ "The Copper Treasure by Melvin Burgess". Fantasticfiction.com. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ↑ "River Thames "Mudlarks" Dig Up Medieval Toys". Archived from the original on 5 May 2004. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ↑ Doeser, James (22 July 2009). "Museum of London Unveils Huge Collection of Buttons". The Council for British Archaeology. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

Bibliography

- Arscott, David (2006). Wunt Be Druv: A Salute to the Sussex Dialect. Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-84674-006-0.

External links

- H. Mayhew, London Labour and the London Poor: "Narrative of a Mudlark"

- Origin of the word

- Home of Mudlarking on the River Thames Warning: Site contains flashing images.