U.S. Route 80 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ocean-to-Ocean Highway The Broadway of America Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway | ||||

1951 alignment of US 80 highlighted in red US 80 Alt. highlighted in blue | ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by ASHD | ||||

| Length | 497.80 mi[1][2] (801.13 km) Mileage reflects US 80 as it was in 1951. | |||

| Existed | November 11, 1926–October 6, 1989 | |||

| History | Western terminus at I-10 in Benson after 1977 | |||

| Tourist routes | ||||

| Major intersections (in 1951) | ||||

| West end | ||||

| East end | ||||

| Location | ||||

| Country | United States | |||

| State | Arizona | |||

| Counties | Yuma, Maricopa, Pinal, Pima, Cochise | |||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

U.S. Route 80 (US 80), also known as the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway, the Broadway of America and the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway, was a major transcontinental highway that existed in the U.S. state of Arizona from November 11, 1926, to October 6, 1989. At its peak, US 80 traveled from the California border in Yuma to the New Mexico state line near Lordsburg. US 80 was an important highway in the development of Arizona's car culture. Like its northern counterpart, US 66, the popularity of travel along US 80 helped lead to the establishment of many unique roadside businesses and attractions, including many iconic motor hotels and restaurants. US 80 was a particularly long highway, reaching a length of almost 500 miles (800 km) within the state of Arizona alone for most of the route's existence.

Along with US 66, US 80 was one of the first U.S. Highways to span Arizona. Where US 66 served northern Arizona, US 80 acted the main interstate highway for the southern half of the state, serving the major cities of Phoenix and Tucson, along with other small towns and cities. The condition of the highway was modernized and improved during the Great Depression, largely through manual labor and funding provided by the Works Progress Administration, which included the grade separation of railroad crossings and paving of the highway. Tourism and traffic along US 80 greatly increased following the end of World War II, creating a temporary economic boom for businesses along the highway. Several areas of the highway were also bypassed or straightened during this time to help alleviate the increasing traffic.

Due to the creation of the Interstate Highway System in 1956, both Interstate 10 and Interstate 8 gradually replaced US 80 as a major highway. Many towns and communities along the highway fell into an economic decline after Interstate bypasses caused a decrease in tourism and patronage. Since US 80 was largely concurrent or bypassed by Interstate Highways across Arizona, the older U.S. Highway was seen as a redundant designation. The US 80 designation was removed from Arizona between 1977 and 1989. The remaining stand-alone sections of US 80 in Arizona, not concurrent with other highways, were re-designated as State Route 80, a northern extension of SR 85 and various Interstate business loops. In September 2018, the Arizona Department of Transportation designated many surviving segments of the former highway as Historic U.S. Route 80, making it the fourth state-recognized historic route in Arizona's history.

Route description

Within the state of Arizona, US 80 made two indirect loops to both Phoenix and Douglas. Both loops were often bypassed by travelers, using the more direct routes of SR 84 and SR 86 respectively to decrease travel time between California and New Mexico.[3] The odd shape created by the two "loops" gave US 80 a long length through the state of Arizona, which was around 500 miles (800 km) in total. In 1935, US 80 was 500.5 miles (805.5 km) long.[4] By 1951, the total length had reduced to about 498 miles (801 km), shrinking further to 488 miles (785 km) in 1956 with the bypass of Arlington and the Gillespie Dam.[5] The following route description roughly describes the path of US 80 as it would have been in 1951.[1]

Yuma to Phoenix

North of the 1914 Ocean-to-Ocean Bridge, the state border between California and Arizona briefly exits the Colorado River and makes its way through the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation, placing several acres of land on the California side of the river in Yuma County, Arizona. It is at this land border that US 80 entered Arizona on present-day Quechan Road in front of a now-abandoned Agricultural Inspection Station. The highway turned to head south across the Ocean-to-Ocean Bridge, entering Yuma on Penitentiary Avenue. Penitentiary curves west at the remains of Yuma Territorial Prison, becoming 1st Street, passing the downtown district of Yuma. The historic Hotel San Carlos, now an apartment building, is located at the curve where Penitentiary becomes 1st.[6]

A few blocks west at 4th Avenue, US 80 had its first major highway junction in Arizona with State Route 95, which came in from the west on 1st Street. Both US 80 and SR 95 turned south joining the route of present-day I-8 Business, sharing a wrong-way concurrency. At 16th Street, SR 95 split off and headed east towards Quartzsite.[7] Today, 16th Street carries US 95, the successor to SR 95. At 32nd Street, US 80 curved east, skirting the north end of Yuma International Airport. Past Avenue 8½ East, I-8 takes over the route of US 80, save for a small area near Exit 14, where US 80 followed the South Frontage Road for less than a mile. US 80 mostly followed the route taken by the I-8 westbound lanes over Telegraph Pass, before splitting off onto East Highway 80 through Ligurta. The highway then used an underpass to clear the Southern Pacific Railroad mainline (now part of the Union Pacific Railroad), paralleling the tracks east into Wellton and becoming Los Angeles Avenue through town.[1][2][6]

Between Yuma and Phoenix, US 80 paralleled the Gila River. East of Wellton, US 80 continued to parallel the Southern Pacific into Mohawk Pass, where it once again took on the route of I-8, then continued straight ahead onto Old Highway 80 into the town of Dateland, iconic for its large date palm orchard. The highway continued east from Dateland on what is now the south frontage road of I-8. Around Tenmile Wash was where the small highway and railroad town of Aztec once stood. Today, all that remains of Aztec is an isolated water tower between old US 80 and the tracks. Past Aztec, US 80 used the eastbound lanes of I-8 crossing the Maricopa County line before heading through Sentinel. Sentinel was a common stop for highway travelers using US 80, being home to a gas station. Today, a different gas station at Sentinel serves I-8 travelers.[1][2][6]

US 80 then continued onto the south frontage road from Piedra through Theba and Smurr before finally reaching Gila Bend, becoming Pima Street. Today Pima Street acts as both I-8 Business and SR 85. The intersection of Martin Avenue and Pima Street served as the northern terminus of SR 85, which itself has since replaced US 80 to Phoenix. Gila Bend is home to the iconic 1961 vintage Space Age Lodge, a motel with an outer space theme sporting a fake alien spaceship on its roof. The oldest remaining building in Gila Bend, the former Stout Hotel, is also located on former US 80 in town.[1][2][6] US 80 turned north towards Phoenix, leaving Pima Street at Old Highway 80. The rest of the I-8 Business loop east of this point was formerly SR 84 to Casa Grande. The old highway parallels the Gila Bend Canal through Cotton Center and crossed over an old concrete bridge (now destroyed with only one span left standing) then curved northwest, arriving at the eastern bank of the Gila River near the ruins of the Gillespie Dam.[1][2][6]

US 80 crossed the 1927 Gillespie Dam Bridge over the Gila River, where it immediately turned north on the other side of the river. After heading north a short distance, the highway turned northeast near Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station and passed through Arlington. East of Arlington, US 80 then before turned east, crossing over the Hassayampa River into the town of Hassayampa. At Wilson Road, US 80 turned north, then east onto Hazen Road. At SR 85, the highway traveled north to the next major intersection with MC 85, then curved east into the town of Buckeye as Monroe Avenue. Buckeye marks the western end of the Phoenix metropolitan area. Heading east from Buckeye, US 80 used both MC 85 and Buckeye Road, through the Phoenix suburbs of Goodyear and Avondale. East of Avondale and present-day Loop 202, US 80 entered Phoenix proper. At 17th Avenue, US 80 left Buckeye Road, heading north past the Arizona State Capitol to Van Buren Street. At Van Buren St., the highway headed east again to an intersection with 7th Avenue and Grand Avenue, where it met US 60, US 70 and US 89. East of Grand Ave., US 80 shared a long concurrency with the other three U.S. Highways through the eastern half of the Phoenix area.[6][1][2]

Phoenix to Tucson

Passing through downtown Phoenix on Van Buren Street, US 60/US 70/US 80/US 89 turned southeast where the Phoenix Zoo is today, arriving at an interchange with Washington Street (now Center Parkway). Washington Street was an unsigned bannered route of US 80 known as US 80 Alternate.[8] South of the intersection, the highways used the 1931 Mill Avenue Bridge to cross the Salt River into downtown Tempe. At 13th Street, the four highways curved east, passing the Arizona State University main campus onto Apache Boulevard. Apache Boulevard becomes Main Street through downtown Mesa. This was where the quartet of U.S. Highways met SR 87. In 1951, the junction with Main Street and SR 87 was the northern terminus of the latter highway.[1][2][6]

US 60/US 70/US 80/US 89 continued east across the Pinal County line onto the beginning of the Apache Trail into Apache Junction. Apache Trail split from the old highway, becoming SR 88 as it headed to Tortilla Flat. From the junction with SR 88, US 60/US 70/US 80/US 89 angled southeast down Old West Highway and continued straight from Goldfield Road, becoming present day US 60. The highways continued down the modern US 60 past present day Gold Canyon to Florence Junction. US 60/US 70/US 80/US 89 diverged from present day US 60 north of the current diamond interchange with SR 79 (Exit 212), taking El Camino Viejo east to an at-grade intersection with SR 79. At this intersection, US 60 and US 70 diverged from US 80 and US 89. Running concurrently, US 60 and US 70 continued east on El Camino Viejo and present-day US 60 towards Superior and Globe. US 80 and US 89 took SR 79 south, crossing the Gila River a second time, into Florence.[1][2][6]

In Florence, US 80 and US 89 split from SR 79 at the state prison, going west on Ruggles Street, then south on Main Street through downtown. The junction with Main Street (SR 79 Business) and SR 287 on the south side of town served as the eastern terminus of SR 287 in 1951. From here, US 80 and US 89 went southeast on SR 79 Business, returning to SR 79. Just south of Florence on the side of the highway is a roadside memorial to cowboy western actor Tom Mix. It was not far from this position in 1940 that Mix was killed when his car slid off US 80/US 89 into a small wash. US 80/US 89 continued south to Arizona at the southern terminus of SR 77.[1][2][6]

US 80/US 89 continued south on current SR 77 across the Pima County line where the highway becomes Oracle Road. Both highways passed through the town of Oro Valley on the western side of the Santa Catalina Mountains before crossing the El Rillito river into Tucson. Where SR 77 turns west onto Miracle Mile was where US 80 and US 89 met SR 84.[1][2][6] This intersection was formerly a large traffic circle. South of this point, Oracle Road was once part of Tucson's Miracle Mile District, a former bustling business district lined with historic motels and iconic structures. US 80, US 89 and SR 84 continued south on Oracle Road, then east at another large traffic circle on to Drachman Street through the Miracle Mile District, passing the iconic Tucson Inn before reaching the end of the Miracle Mile at Stone Avenue.[9][10]

The three highways proceeded to curve south onto Stone Avenue, passing the 1936 Art Deco-styled Old Pueblo Service Station before taking the Stone Avenue Underpass, a decorative Gothic Style 1939 underpass, to cross the Southern Pacific Railroad into downtown. US 80, US 89 and SR 84 continued on Stone Avenue through downtown to the Five Points intersection at 18th Street and 6th Avenue, where Stone ended. The highways from this point used 6th Avenue to continue south through the enclave of South Tucson, passing a few more historic 1930s era motels. Sixth Avenue met Benson Highway at an intersection just north of the Southern Arizona Veterans Affairs Hospital. Today, this part of Benson Highway is now I-10. SR 84 ended at this intersection, while US 89 continued south on 6th Avenue to Tubac and Nogales. US 80 turned east onto present-day I-10, passing the historic Old Spanish Trail Inn right before curving southeast onto Benson Highway.[1][2][6][10] Benson Highway has a row of neon-signed motels that stretch southeast out of Tucson towards Vail, including the iconic Spanish Trail Inn, which now stands partially abandoned. US 80 then continued southeast on Benson Highway, exiting Tucson.[1][2][6]

Tucson to the New Mexico state line

At Valencia Road, US 80 continued towards Vail along present-day I-10, passing the Triple T Truck Stop at Craycroft Road along the way. Near Vail, US 80 diverged from I-10 onto the north frontage road, crossing a decorative wash bridge. Going south of Vail past the northern terminus of SR 83, US 80 went northeast through small foothills on Marsh Station Road, crossing Ciénega Creek over the historic 1921 Ciénega Bridge. The highway then arrived in the small town of Pantano. Today, Pantano is a ghost town, with few structures still standing. US 80 continued southeast on Marsh Station Road, returning to the routing of I-10, then crossed the Cochise County line. Just across the county line, US 80 made a small curve onto Titan Drive, crossing under the now-abandoned El Paso and Southwestern Railroad before returning once again to the route of I-10. Arriving in Benson, US 80 headed east onto 4th Street (now I-10 Business) through the town center. US 80 met the western terminus of the eastern section of SR 86 at a 1941 interchange/underpass complex. SR 86 continued east on I-10 Business and I-10 towards Willcox and New Mexico, while US 80 turned south on what is now SR 80. US 80 then passed through St. David as Patton Street and Lee Street, heading towards Tombstone.[1][6][2]

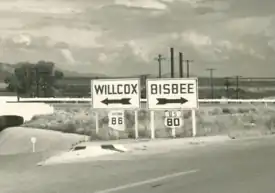

Passing the eastern terminus of SR 82 near Fairbank, US 80 came into Tombstone on SR 80 and Sumner Street. At Fremont Street, US 80 continued southwest for one block to Allen Street, then continued southeast on Allen through the heart of Tombstone, passing the O.K. Corral and the site of the infamous gunfight. The highway turned northeast on to 6th Street for one block, then turned southeast on to Fremont Street. US 80 exited Tombstone on Fremont Street, before continuing southeast on SR 80, passing the eastern terminus of SR 90. At the intersection with Old Divide Road, US 80 headed south over Mule Pass on the winding mountain road over what was once believed to be the Continental Divide. On the other side of the pass, US 80 then curved east onto Tombstone Canyon Road, entering the mining town of Bisbee.[1][2][6]

Entering downtown Bisbee, US 80 became Main Street, winding its way past the historic Copper Queen Hotel. On the east side of downtown, the highway continued east on SR 80 at the Copper Queen Mine and skirted the edge of the massive Lavender Pit mine, curving onto Erie Street and entering downtown Lowell. US 80 then passed under the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad, meeting SR 92 at its eastern terminus before running northeast of Warren through Grace Corner towards the Mexican border.[1][2][6][11] Near the border, US 80 turned directly east, meeting the southern terminus of US 666 before crossing under the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad again, heading into Douglas, Arizona.[1][2][6]

Upon arriving in Douglas, US 80 passed a large copper smelter on the south side of the highway, before entering downtown Douglas on G Avenue.[6][12] Once downtown, US 80 passed by the historic Gadsden Hotel and turned west onto 10th Street. After going a few blocks east on 10th Street, the highway then went north onto A Avenue. It then turned east again, onto SR 80, with the El Paso & Southwestern Railroad paralleling it to the north. East of Douglas, US 80 entered the small ghost town of Apache, which was home to three buildings, including a two-story general store. Off the side of the road near Apache is a stone cone-shaped monument marking the event of Geronimo's surrender, which occurred just southeast of this point in 1886. US 80 then reached the New Mexico state line, where it continued east to Rodeo and Lordsburg.[1][6][2]

History

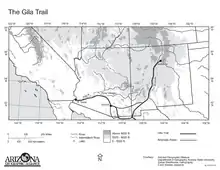

The history and background surrounding the Arizona section of US 80 dates back to pre-Columbian Native American culture and society. It was originally a section of the ancient Gila Trail.[13][14] When it was a commissioned U.S. Highway, US 80 was a popular and heavily promoted transcontinental route between California and Georgia. There were several tourist attractions and historical sites along the route.[12] As a result, US 80 had a profound effect on Arizona's economic development and car culture, much like US 66 had done in the northern part of the state.[15] The highway was ultimately replaced by the Interstate Highway System as a major route. This led to a decline in popularity of US 80 and its eventual decommissioning within the western United States.[9][16] In recent years, the popularity of US 80 has increased, leading to it being designated a historic route in multiple states.[17]

Background

The general path of the Gila Trail in Arizona was traversed by Native Americans for thousands of years. The first non-Native person to travel the Gila Trail was a Spanish-owned African slave named Esteban, who had been brought to North America in 1527 as part of the colonization of Florida by Charles V of Spain. In 1538, Esteban accompanied a Franciscan friar by the name of Marcos de Niza on a journey, which included travelling along the Gila Trail.[14][18] Father Eusebio Kino utilized the Gila Trail to establish missions across present day southern Arizona and California.[19] In 1821, southern Arizona had become part of Mexico.[20]

The first Americans on the trail were 19th Century fur trappers, who made use of the nearby Gila River's beaver population. During the Mexican–American War Lieutenant General Stephen W. Kearney of the United States Army sent his Army of the West over the Gila Trail.[21] Following the Mexican-American War, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 and the Gadsden Purchase in 1853, the land surrounding the Gila Trail became part of the United States and was organized as New Mexico Territory in 1850.[22][23] After 1848, Gila Trail had become a popular and heavily traveled wagon route to California. By this time it was now known as Cooke's Wagon Road. The new name was in reference to Captain Philip St. George Cooke, leader of the Mormon Battalion, whom had used the road shortly after General Kearny.[24] In 1863, the western part of New Mexico Territory was re-established as Arizona Territory.[20][22]

By 1909, Cooke's Wagon Road had become segments of the East-West Territorial Road and North-South Territorial Road respectively. The former route traveled between Yuma and Phoenix to Duncan while the latter traveled between the Grand Canyon region, Phoenix, Tucson and Douglas.[25] In February 1912, Arizona was accepted into the union as a state, which led to the reorganization of the Territorial Road system into Arizona's true State Highway System.[20][22][25] When the first set of reorganizations were complete in 1914, the North-South Territorial Road between Phoenix and Douglas as well as the East-West Territorial Road between Yuma and Phoenix were reorganized into a new state highway known as the Borderland Highway.[20]

Using funding from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Ocean to Ocean Bridge was constructed between Winterhaven, California, and Yuma in 1914. It carried the Borderland Highway over the Colorado River. The bridge's namesake was the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway, which was a common name given to the Borderland Highway between Yuma and Phoenix.[26][27] Between 1917 and 1919, the Dixie Overland Highway was established from Savannah, Georgia, to San Diego, California, becoming the first auto trail to be designated over the Borderland Highway.[16] From Yuma to New Mexico, the Dixie Overland Highway followed the basic route of the Borderland Highway very closely.[6] The route also became part of the Bankhead Highway in 1920 and the Old Spanish Trail in 1923.[6][16][28]

In 1919 and 1920, the Borderland Highway between Dome and Buckeye suffered extensive damage from flooding. This was due to the route being located on the Gila River floodplain. The Arizona State Highway Department (ASHD) decided to construct a new alignment further south, following the Southern Pacific Railroad more closely through Gila Bend. The new route was completed in 1922.[29] Up to 1924, the Bankhead Highway, Dixie Overland Highway and Old Spanish Trail still followed the older route.[30] By 1925, the trio of auto trails had been moved to the newer alignment of the Borderland Highway, while the new alignment was being paved.[31] Within the same time frame as the Gila Bend realignment, improvement work also occurred on the eastern section of the Borderland Highway. Between 1917 and 1922, a section of the Borderland Highway southeast from Bisbee towards Douglas was paved. This section of the Borderland Highway and a section of the Roosevelt Dam Highway further north were the first two paved highways in the state of Arizona.[25]

The Arizona State Highway Department, with the assistance of federal financial aid as well as financial aid from both Pima and Cochise counties, constructed a new improved alignment of the Borderland Highway between Benson and Vail, completed in 1921. This project was known as Federal Aid Project Number 18. As part of this highway construction project, the Ciénega Bridge, an open-spandrel concrete arch east of Tucson, was constructed between 1920 and March 1921. The new bridge came at a total cost of $40,000 (which was approximately $522,124 in 2022).[32][33] The state highway system was re-organized again, following the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921. As a result, the Borderland Highway was re-designated into entirely new named state routes. The Borderland Highway became the Yuma–Phoenix Highway, the western section of the Phoenix–Globe–Rice Highway (present-day US 70), the Florence Junction–Tucson Highway, Tucson–Benson–Bisbee Highway and the Bisbee–Douglas–Rodeo Highway. Later in the 1920s, paving of the Tucson–Benson–Bisbee Highway through Mule Pass near Bisbee was completed using prison labor. This section of road had already been rebuilt in 1911, from a mostly unaltered 1881 wagon road.[34]

U.S. Highway designation and early improvements

In April 1925, the Joint Board on Interstate Highways was appointed by the Secretary of Agriculture to simplify the transcontinental highways. The joint board proposed a new nationwide highway system, with a uniform standard of signage and numbering. This system was to become the U.S. Numbered Highway System. By October 1925, a new route under the numeric designation "80" was proposed along a similar path to the Dixie Overland Highway, Old Spanish Trail and Bankhead Highway.[16] This meant that the new stretch of US 80 was to be placed over the entirety of the old Borderland Highway route.[25] On November 11, 1926, the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) approved of the new system, which included U.S. Route 80 between Savannah and San Diego.[16][35] Both US 80 and another U.S. Highway to the north, US 66, were the first transcontinental U.S. Highways to span the entire length of Arizona. Both highways connected the major towns and cities in Arizona with California and the eastern United States, with US 80 serving southern Arizona while US 66 served the northern part of the state.[35] However, the Arizona State Highway Department did not recognize US 80, US 66 or any other U.S. Highways within the state until September 9, 1927. After this date, the U.S. Highway designations were included with new numbered state routes as the entirety of the new Arizona State Highway System.[36]

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

In 1928, US 80 became part of the Broadway of America auto trail.[37] The new auto trail traversed multiple U.S. Highways and state routes from New York City to San Diego. In Arizona, Broadway of America followed US 80 between Yuma and Phoenix as well as between Tucson and the New Mexico border. The rest of the Broadway of America in Arizona consisted of SR 87 and SR 84 between Tucson and Phoenix via Casa Grande.[6] Despite the new U.S. Highway designation and Broadway of America designation, the Dixie Overland Highway, Bankhead Highway and Old Spanish Trail designations would continue into the early 1930s.[38]

With new U.S. Highway status came great changes and improvements. In 1927, the steel truss Gillespie Dam Bridge was constructed over the Gila River next to the Gillespie Dam. Prior to the construction of the bridge, traffic utilized a concrete apron constructed at the foot of the dam to cross the river. At the time, the Gillespie Dam Bridge was the largest steel structure in the state of Arizona.[39] In 1928, the section of US 80 through Telegraph Pass was constructed and would be paved by 1930.[40][41] The paving work on the highway east of Douglas was under way as well by 1930.[41] 1930 also marked the year catastrophic flooding washed out US 80 through the town of Wellton. The town itself was also mostly destroyed by the flood. This led to the highway department having to construct an entirely new alignment north of the older one. The town center of Wellton was also reconstructed on the new alignment. The new alignment became the main street of Wellton, and was named Los Angeles Avenue.[6] In 1931, the Mill Avenue Bridge in Tempe was constructed to carry US 80 and US 89 across the Salt River.[42] The Mill Avenue bridge replaced the earlier 1913 Ash Avenue Bridge, which had carried both highways between Phoenix and Tempe since 1926.[6]

Paving on US 80 between Douglas and New Mexico was also completed in 1931, as was the entire highway between Yuma and Phoenix.[43] By 1932, US 80 was fully paved between Tucson and Vail as was the highway between Florence Junction and Florence. That year, more of US 80 had been improved and better surfaced than US 66.[44] In response, a group of US 66 proponents from northern Arizona traveled to Phoenix on May 8, 1932, and demanded the State Highway Commission to block further funding to improve US 80 entirety of US 66 had been improved. The commission ultimately denied the delegation's demands and did not place a restriction on funding for improvements on US 80.[45] Further paving occurred between Oro Valley and Tucson as well as between Benson and Bisbee between 1932 and 1934.[46] By 1935, most of US 80 was paved within the state of Arizona, save for a small section between Florence and Oracle Junction. The sole remaining unpaved section was instead surfaced with rock and gravel. Travelers wishing to stick to paved roads between Phoenix and Tucson had the option of using SR 87 and SR 84 through Casa Grande.[4]

Passage of the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935 by the United States federal government allocated over $200 Million ($3.38 billion in 2022) in federal funding to road construction across the country.[25][33] Of this funding, the state of Arizona allocated over $6 million ($101 million in 2022) for statewide highway improvement the following year; much of this funding was allocated to US 80, for constructing and rebuilding alignments and bridges as well as improving water drainage along the highway.[47][33] Emergency Relief Appropriation Act also provided another $200 million ($3.38 billion in 2022) to all territories and states to rebuild or replace unsafe railroad grade crossings on state and federal highways. This allowed the Highway Department to construct two railroad underpasses on US 80 in 1936. The first overpass was constructed on Stone Avenue in Tucson and the second was constructed in Douglas, with both overpasses providing safe crossings of the Southern Pacific Railroad. The Tucson underpass also included pedestrian walkways besides the four traffic lanes of US 80.[25][32][33] Further west, WPA funding was being used to rebuild US 80 between Phoenix and Buckeye.[48] Further aid on US 80 was supplied by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which provided the state with extra funding and a labor force to reconstruct the highway.[49]

In 1936, real estate developer Stanley Williamson laid out a business district proposal for the Tucson area. Williamson aimed to rebuild a large section of US 80 and US 89 north of downtown, as well as a small segment of SR 84, into a thriving commercial district. The new district was similar in design and principle to the Miracle Mile in Los Angeles, California. Originally, the glorified roadway along the three highways was to be named "Parkway Boulevard" but Williamson decided instead to call the proposed district Miracle Mile after its inspiration.[50] These plans also called for a section of US 80 and US 89 between Drachman Street and SR 84 to be reconstructed. Known as Oracle Road, the section of road was rebuilt into a four lane divided highway to handle larger traffic volumes and promote business growth as well as further highway improvements. The rebuild would also include two large traffic circles at either end of the four-lane section with SR 84 and Drachman Street. Reconstruction of Oracle Road (US 80 and US 89) was awarded to the Tanner Construction Company in 1937 and completed within the same year. Not long after construction, motels began appearing along the new Miracle Mile, marking the beginning of what would become a successful business district.[9] The widened section of Oracle Road was also the first divided highway in Arizona.[25]

On October 12, 1940, Hollywood cowboy western actor Tom Mix left the Oracle Junction Inn at the intersection of US 80, US 89 and SR 77, heading north by car on US 80 and US 89 towards Florence. Later that same day, Mix lost control of his vehicle on the unpaved road and was killed instantly when his car crashed into an unfinished wash bridge just south of Florence.[51] Today, a memorial to Mix stands near the exact spot where he lost his life on the highway.[6] By 1946, the section of US 80 between Florence Junction and Oracle Junction was finally reconstructed and paved. The completion of the 1946 project meant every section of US 80 in Arizona was now a fully paved modern highway from Yuma to New Mexico.[52]

The boom years

On April 15, 1947, a group of US 80 proponents met at the Pioneer Hotel in downtown Tucson to discuss the improvement of tourism on US 80 through the American southwest. The small group had studied tourism statistics along the route following the end of the Second World War. The findings concluded tourism on US 80 had exponentially decreased since the 1930s. In response, the proponents voted to form a California, Arizona and New Mexico division of the U.S. Highway 80 Association to better promote US 80 to cross country tourists.[53] In June 1949, the western division of the U.S. Highway 80 Association was formally established with Tucson chosen as its headquarters. The division committed itself to publishing thousands of informational booklets, strip maps and pay for roadside advertisements all in an effort to promote the highway. Membership was also offered to local businesses on the route between San Diego and El Paso, Texas.[54] By November 1949, the western division of the U.S. Highway 80 Association had printed over 50,000 promotional strip maps of US 80 between San Diego and El Paso. The maps were distributed to multiple gas stations and chambers of commerce along the western section of the highway.[55]

In the following years, the highway's popularity increased dramatically. During the 1950s, more motorists traveled on US 80 between Arizona and California than on the famous US 66.[3] Approximately 2,500 cars travelled on US 80 each day by the middle of the decade. Arizona's five largest cities of the time were also located along the highway.[12] Like its northern counterpart, US 80 also featured many iconic road side businesses and attractions, which included Boothill Cemetery and the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Stoval's Space Age Lodge in Gila Bend, Yuma Territorial Prison, the Geronimo Surrender Monument near Douglas and the Painted Rock Petroglyph Site. Rows of iconic neon signed motels aligned US 80 in the many towns and cities it passed through, including Tucson's Miracle Mile. High demand for motel rooms by U.S. Army personnel and the postwar population boom in Tucson resulted in an explosive growth of hotel and restaurant construction on Miracle Mile and Benson Highway southeast of downtown.[9] As of 2016, many of these attractions and structures have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[13] Further adding to the increased success, the January 1956 issue of Arizona Highways magazine was partially dedicated to the state's section of US 80.[12]

Construction and improvement work continued on US 80 through the 1950s. In 1950, the Phelps Dodge Corporation and Bisbee Chamber of Commerce entered a cooperative agreement to create a new open pit mine. The new mine would be named the Lavender Pit after H.M. Lavender, the vice president and general manager of Phelps Dodge. Phelps Dodge would pay the expenses of moving the displaced residents and utilities, including US 80 itself, which ran through the proposed pit area. The project of relocating US 80 was awarded to the A.J. Gilbert Construction Company of Warren, Arizona. The relocation of US 80 and all other displaced persons and utilities was completed between January and April 1951. US 80 now ran the edge of the new open pit mine. An observation tower was also constructed on the new alignment of US 80 to view the pit from. Soon after, work began on stripping and excavating the land officially opening the Lavender Pit. In total, the project cost $25 Million ($227 million in 2022) and required 250 total structures to be demolished and relocated. It also resulted in the total removal of the Johnson Addition district of Bisbee.[56][33]

In May 1954, the Arizona Highway Commission and California Highway Department approved the construction of a new bridge over the Colorado River in Yuma. The new bridge would replace the 1914 Ocean To Ocean Bridge. The new bridge site was selected five blocks west of the existing bridge and would carry 4th Avenue across the river into Winterhaven. Both states would split the cost of construction.[57] 4th Avenue was extended to the south approach of the proposed bridge in June 1954 with planning on the California approach completed the same month.[58] Management of the bridge's construction was undertaken by the California Highway Department.[59] The bridge itself was designed by engineers within the state of California. By November 1955, construction on the bridge was well under way on both sides of the river by the California-based Fred J. Early Junior Construction Company. A $53,000 ($454,176 in 2022) inspection station was built on the Arizona side as part of the project.[60][33] The bridge was opened to traffic on May 13, 1956, in a dedication ceremony conducted by officials from both states. Attending was Arizona governor Ernest McFarland, who gave the main address at the ceremony. The bridge cost a total of $1,236,000 ($10.2 million in 2022) to complete.[61][33] US 80 was rerouted over the new bridge, with the old route over the 1914 bridge becoming US 80 Business.[60]

.jpg.webp)

Two straighter and faster alignments of US 80 were constructed in 1955 and 1956, bypassing the Gillespie Dam area and Ciénega Creek.[5] The Ciénega Creek bypass was the first to be constructed. The original winding route over the 1921 bridge had developed a dangerous reputation. Between 1952 and 1955, 11 people were killed in separate car accidents on the Ciénega Creek section of US 80. Construction on the bypass began in 1952 and required a total of 805,000 cubic yards (615,467 m3) to be excavated and moved to accommodate the new roadway. Two new bridges had to be constructed over Ciénega Creek and Davidson Wash as well as an underpass to allow the new section of US 80 to travel underneath the Southern Pacific Railroad. Opening on April 9, 1955, the new section of highway cost $1,397,000 ($12 million in 2022) to construct. The highway was originally two lanes wide with space added for a third lane under the new railroad overpass should traffic volumes increase in the future.[62][33]

The Gillespie Dam bypass of US 80, which traveled between Gila Bend and Buckeye, was completed in May 1956. It was also used to test an experimental safety feature by the Highway Department. Double white intermittent stripes were placed down the center of the new highway in hopes it would help increase visibility of the center line for traffic driving the highway at night and to place heavier emphasis for drivers on staying within their designated lane. The new section was originally 29 miles (47 km) long with a total width of 40 feet (12 m). The two individual lanes were 12 feet (4 m) wide each, complemented with the addition of an 8 feet (2 m) shoulder. In total, the new route was about 10 miles (16 km) shorter than the original route past the Gillespie Dam and saved approximately 30 minutes of travel time for commuters between Buckeye and Gila Bend. When this section of road first opened, it carried up to 12,000 cars and trucks in a single day.[63] In 1961, the Arizona Highway Commission voted to designate the entirety of US 80 in Arizona as part of the Jefferson Davis Highway.[64]

Construction of the Mule Pass Tunnel

By far the largest combined roadway improvement project on US 80 in the 1950s was the construction of the Mule Pass Tunnel and adjoining bypass of downtown Bisbee.[65][66] Originally constructed as a wagon road in December 1881 and becoming a paved auto highway by the 1920s, the older route of US 80 over Mule Pass (also known as the Old Divide) provided a dangerous obstacle for vehicles heading into Bisbee. It was a common occurrence for large trucks to lose their brakes on the steep grades, resulting injury and in worst cases, death. Furthermore, winter snowfall and ice made crossing the Old Divide sometimes impossible. Plans had been in place since the 1930s to replace the treacherous route with a tunnel. By the 1950s however, US 80 still utilized the Old Divide routing with no tunnel having been constructed.[67][68]

In April 1955, the Arizona State Highway Department began studying the feasibility of constructing a tunnel to bypass the older route of US 80 over the Old Divide. The proposed tunnel was 34 feet (10 m) wide and 1,200 feet (370 m) long and would take US 80 under the pass. Initial survey would require the boring of a pilot tunnel at the proposed tunnel site.[69] As planning continued, the proposed length grew from 1,200 feet (370 m) to 1,400 feet (430 m). The new Mule Pass Tunnel would be the longest tunnel in the state of Arizona upon completion, surpassing the Queen Creek Tunnel on US 60 in Globe. On November 13, 1956, the Highway Department opened bidding for the tunnel project, with the low bid set at $1,983,659 (equivalent to $17 million in 2022).[70][33] The original completion date was set for August 31, 1958.[70] The contract was awarded to Peter Kiewitt and Sons Company of Phoenix on November 25. At the time, it was the largest highway construction contract ever awarded in Arizona's history.[65]

In January 1957, the Arizona State Auditor, Jewel Jordan, rejected the contractor's first claim for $15,000 ($120,081 in 2022) in payment regarding tunnel work completed up to that point. Jordan claimed her rejection of the initial payment was due to the contract being illegal, being $600,000 ($4.8 million in 2022) over the original allocated budget.[71][33] This led to the Highway Department petitioning the state Attorney General, Robert Morrison, to look into the legality of the tunnel contract in order to secure payment to the contractor from the state. Morrison took the side of the highway department. Due to the dispute between Jordan and Morrison, the matter had to be brought to the Arizona Supreme Court for ultimate decision.[71] Morrison filed the case as a lawsuit on behalf of the Highway Department, with Jordan acting as respondent. The outcome of the suit would determine the legality of the contract.[72] On March 5, 1957, the court ruled the contract was legal, despite being over budget.[73] When financial issues were settled, the state of Arizona ended up paying for 28 percent of the cost, with the remainder being reimbursed by the Federal Government.[68]

Initial work on the tunnel itself began on January 9, 1957, with excavation work commencing on the Bisbee end of Mule Pass.[74] By August 10, the construction crews were excavating an average of 2,700 cubic feet (76 m3) per day. This broke the world record of most earth excavated by a drilling machine per day, breaking the previous record of 2,562 cubic feet (72.5 m3) set in Australia. The tunnel crew exceeded their own record twice by September, first increasing to 2,873 cubic feet (81.4 m3) of material excavated per day, then further to 3,106 cubic feet (88.0 m3) of material per day.[75] By October 6, over 1,100 feet (340 m) of tunnel had been excavated. The width of the tunnel was now 42 feet (13 m) wide, exceeding the original proposed width. The tunnel also measured 21 feet (6.4 m) in height at an elevation of 5,894 feet (1,796 m) above sea level.[74] As the tunnel was excavated, the bore was supported by multiple steel reinforcing beams.[76]

By October 30, construction crews finally broke through to the other side, opening the western portal for the first time.[76] By June 1, 1958, the completion date for the tunnel had been extended to October 23 of the same year and construction crews had lined half the walls of the tunnel with concrete.[68] When the tunnel was completed in late 1958, over 93,000 short tons (84,000,000 kg) of earth material had been excavated, with 446 steel supporting ribs installed along with 210 short tons (190,000 kg) of reinforced steel at both portals. The walls of the tunnel had concrete lining 31 feet (9.4 m) thick. The tunnel carried three lanes of traffic, with two lanes being westbound and the third for eastbound traffic.[77] The tunnel was supposed to be opened to traffic on December 12, but due to weather delays, the dedication ceremony was postponed to December 19.[78] The Mule Pass Tunnel was opened in a dedication ceremony on December 19, 1958. The ceremony itself took place at the eastern portal.[79] Governor McFarland attended the ceremony, cutting a copper braided ribbon.[77]

Complementing the Mule Pass Tunnel was the construction of a limited access bypass around downtown Bisbee, also part of US 80. Construction for the first 1.1 miles (1.8 km) section of the bypass was awarded to the Tanner Construction Company of Tucson in late 1958.[66][77] Referred to as the "Bisbee Freeway", the bypass was under construction by March 1959 heading south from the Mule Pass Tunnel.[66][80] In April 1960, the Fisher Construction Company submitted the low bid entry for the remaining 1.9 miles (3.1 km) section of the bypass. Fisher Construction addressed the Bisbee public, stating explosives used during the bypass construction would be controlled and not affect nearby buildings or businesses.[81] Fisher Construction was awarded the contract and commenced work on the final stretch of the bypass by January 1961, with work being ahead of schedule.[82] Construction of the bypass did not go without incident however. In September 1961, a segment of the first completed section of the bypass, 150 feet (46 m) long, was observed to be settling into the ground. Investigation of the matter concluded water seepage underneath the roadbed had caused the settlement. Tanner Construction had completed construction of this section of the bypass a year earlier. Test bores were drilled to find the source of the water intrusion and solve the problem.[83]

During construction of the bypass, several historic residences and landmarks were demolished and removed. On September 31, 1961, construction of the two lane Bisbee Freeway was completed. Arizona State Highway Department officials, Bisbee Chamber of Commerce officials and 100 citizens of Bisbee turned out to attend the dedication. A line of new cars provided by local auto dealers carried officials over the newly completed bypass. The officials became the first motorists to use the new section of US 80. The new bypass redirected US 80 traffic off Tombstone Canyon Road and Main Street, the original highway through the heart of Bisbee itself. Despite the convenience of the new freeway, local motorists preferred the original route over the Old Divide and through town.[84] Today, the Mule Pass Tunnel remains the longest tunnel in the state of Arizona.[6]

Replacement by Interstate highways

Following the establishment of the Interstate and Defense Highway System by August 1957, two new highways, Interstate 10 and Interstate 8, were both slated to replace US 80.[48][85] In 1948, the Arizona State Highway Department approved construction of the Tucson Controlled Access Highway, a freeway bypass around the core of Tucson. This would become one of the first sections of I-10. Though a state highway, initial construction of the bypass was funded by a 1948 city bond issue passed by the city of Tucson.[9][86] The construction contract was awarded to the Western Construction Company on November 9, 1950, for $407,000 ($3.95 million in 2022).[87][33] Construction on the freeway began on December 27.[88] During construction, the Santa Cruz River had to be diverted into a new artificial channel in order to minimize the risk of the river flooding the new freeway.[89] Heavy truck traffic in Tucson on December 20, 1951, caused state highway officials to open the first section of the freeway on the same day, with the next section already under construction.[90] The new highway was signed as SR 84A.[91][92] SR 84A originally ran between Congress Street and Miracle Mile. At first, this bypass lacked overpasses and interchanges between Grant Road and Speedway Boulevard.[9] SR 84A was extended eastward by 1956 to an interchange with US 80 and US 89 at 6th Avenue and Benson Highway.[5] Construction started in 1958 to rebuild SR 84A to Interstate standards.[9]

In 1957, construction work began on a section of US 80 southeast of Tucson. This section, known as Benson Highway, was to be upgraded into a four lane divided highway. Of the 7.25 miles (11.67 kilometres) of upgraded road, 4.25 mi (6.84 km) were slated to become part of I-10 and be rebuilt to full interstate standards. This small section of Benson Highway became the first federally funded Interstate Highway construction project in Arizona.[93] This section was completed by December 1960.[94] The new section of I-10 had full freeway interchanges and frontage roads at Craycroft Road and Wilmot Road with a third planned later for Valencia Road.[93][94] Other sections of US 80 and SR 86 east of Tucson were also being upgraded into new sections of I-10, with a total of four freeway interchanges between Tucson and Benson complete.[94] Other sections were rebuilt into a four lane divided highway around 1958.[95] I-10 west of 6th Avenue and Benson Highway up to Flowing Wells was completed by 1961, with a sections north of Tucson through Marana well under construction.[9]

Construction began on transforming US 80 into I-8 on December 22, 1960, between Sentinel and Gila Bend. Four other sections began conversion in 1961 and 1962 between Gila Bend and Yuma. The Sentinel project was completed on April 18, 1962, at a cost of $1,268,954 ($9.45 million in 2022)[33] and became the first section of I-8 completed in Arizona. The details of the Sentinel project were later investigated by the United States House of Representatives for financial mismanagement of the project by the Arizona State Government.[96] By 1963 construction was under way on rebuilding sections of US 80 and SR 84 between Casa Grande and Yuma into I-8 as well as parts of SR 84 between Picacho and Casa Grande into I-10.[97] Most of I-8 through Arizona was completed by 1971 as well as most of I-10 in the southeastern part of the state. Most of US 80 had been fully rebuilt into I-8 between Blaisdell and Gila Bend, save for a standalone section between Ligurta and Mohawk. In the eastern part of Arizona, I-10 had been completed between 6th Avenue and Valencia Road as well as taking over all of US 80 between Valencia Road and 4th Street in Benson. Both Interstates were complete between Gila Bend and Tucson, replacing or bypassing almost all of SR 84. Between Benson and the New Mexico state line near San Simon, former SR 86 had been rebuilt into I-10 and decommissioned. I-10 was also finished between Casa Grande and I-17 in Phoenix, effectively bypassing US 80 from Phoenix to Tucson.[98]

As construction of the Interstate Highways progressed, remaining sections of US 80 were bypassed and rendered obsolete.[16] As a result, the amount of traffic through business districts along US 80 decreased. The decline in traffic led to motels and other businesses along US 80 receiving fewer customers. Several of these establishments closed permanently and were torn down. Others remained, but greatly declined in quality. As a result, the amount of crime and poverty along US 80 through populated areas grew.[9] Since most of the highway had been replaced with or bypassed by Interstates, western states began viewing the US 80 designation as redundant. Between 1964 and 1969, California retired its section of US 80 in favor of I-8, effectively moving the western end of US 80 to the California state line in Yuma.[16] On October 28, 1977, the Arizona Department of Transportation (also known as ADOT and successor to the Arizona State Highway Department) requested a truncation of US 80 to Benson. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) approved the request, allowing ADOT remove the designation between Yuma and Benson on September 16.[99] However, US 80 signage remained in place between Yuma and Benson until December 27, 1977, when the ADOT directed state highway maintenance crews to remove all remaining references to the highway.[100] Upon retirement of the designation, the section of US 80 between I-8 Business in Gila Bend and US 60/US 89 at Grand Avenue in Phoenix became a northern extension of SR 85.[101]

In 1989, representatives of Arizona and New Mexico at AASHTO requested the elimination of US 80 in both states. The request was mostly approved by AASHTO on October 6.[16] As a result, the remaining section of US 80 in Arizona was re-designated as SR 80.[102] Despite the designation being entirely removed from Arizona, a former section of US 80 between Buckeye and Phoenix had yet to be bypassed. Being signed as SR 85 at the time, the section was still used as a primary route by I-10 traffic through western Phoenix into the early 1980s. This was due to the Papago Freeway, a proposed section of I-10, having not been constructed yet between Buckeye and I-17 near downtown Phoenix. The Buckeye to Phoenix section of SR 85 was finally bypassed in 1990, when the Papago Freeway was completed.[101][103] However, the section of SR 85 between I-10 and Gila Bend, another former section of US 80, has yet to be bypassed or replaced by a freeway. Other sections of old US 80 throughout Arizona pay homage to the retired highway through their names, including Old U.S. Highway 80 through Wellton and Old US 80 Highway between Gila Bend and Buckeye.[6] Although US 80 no longer runs through Arizona, the designation itself is still active between Dallas, Texas and Savannah.[16]

Historic U.S. Route 80

Historic U.S. Route 80 | |

|---|---|

| Location | Yuma–New Mexico border |

| Length | 398.54 mi (641.39 km) |

| Existed | 2018–present |

In 2012, the Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation (also known as the THPF) embarked on preliminary work needed to apply for a state historic designation of US 80 in Arizona. The foundation commenced survey and mapping work on old sections of the route the same year.[17] Over $100,000 was spent by the THPF to initiate the historic designation process.[3] Further research by the THPF utilized essays written for the Arizona Department of Transportation and Federal Highway Administration as well as a US 80 driving guide written by Jeff Jensen. Further resources were obtained through the special collections of the University of Arizona and Arizona Historical Society. Findings by the THPF concluded at least 40 separate segments of former US 80 in Arizona survive un-interrupted.[3]

In July 2016, the THPF finished all necessary preparation work for a historic designation and submitted a formal application for the Historic US 80 designation to the ADOT Parkways, Historic and Scenic Roads Advisory Committee.[17] The proposal included several attached letters of support from various historical committees, mayors and city council members of several towns which the designation would affect.[13] During a meeting on June 20, 2017, the Parkways, Historic and Scenic Roads Advisory Committee decided to unanimously recommend the Historic Route 80 designation to the Arizona State Transportation Board.[17] By August 2018, ADOT was close to completing required reports for the Arizona State Transportation Board needed to sign and designate the segments of Historic US 80 that are part of the state highway system. Currently, ADOT is also working with respective local governing bodies to sign and designate the segments that are no longer part of the state highway system.[3]

On September 21, 2018, all preparation work was complete and the ADOT Parkways, Historic and Scenic Roads Advisory Committee officially adopted Historic U.S. Route 80 as a state designated Historic Road.[104] The Historic Route designation connects to and supplements Historic Route 80 in California.[17] Historic US 80 is the fourth state designated Historic Route in Arizona, joining Historic Route 66, the Jerome-Clarkdale-Cottonwood Historic Road (Historic US 89A) and the Apache Trail Historic Road.[105]

The total mileage of Historic US 80 is 398.54 miles (641.39 km).[106][107][108] The shorter distance of Historic US 80 compared to the original highway is because certain segments of former US 80 are not included in the designation. More specifically, segments that have been rebuilt into I-8 and I-10.[108] This means Historic US 80 is cut up into several non-consecutive segments, existing where the highway has not been directly replaced by the Interstates.[107] This is a similar situation to Historic US 66 in the northern part of the state, which is not designated along parts of US 66 that have been rebuilt into I-40.[105] A primary objective of the designation is to highlight and preserve highway segments and artifacts relating to former US 80, dating between 1926 and 1955, along the designated historic route. This period of the highway's history was deemed to be the most historically significant by the State Transportation Board.[107]

In parallel with the Historic Route 80 designation project, the City of Tucson submitted an application to add a segment of former US 80, known as Miracle Mile, to the National Register of Historic Places in Summer 2016.[17] On December 11, 2017, the application was approved and the segment added to the NRHP became known as the Miracle Mile Historic District. The Historic District includes part of Stone Avenue, Drachman Street, the southern segment of Oracle Road, West Miracle Mile (former SR 84) and a small two block section of Main Avenue south of the intersection of Oracle and Drachman. The Miracle Mile Historic District also includes over 281 man made structures including historic motor hotels among other roadside attractions and local businesses.[109]

Major intersections

This list follows the 1951 alignment.

| County | Location | mi[1][2] | km | Destinations[6][110][111][112] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuma | Fort Yuma Indian Reservation | 0.00 | 0.00 | California state line; state line is on land north of the Colorado River in this area | |

| Colorado River | 0.04 | 0.064 | Ocean to Ocean Bridge | ||

| Yuma | 0.79 | 1.27 | Western terminus of concurrency with SR 95 | ||

| 2.63 | 4.23 | Eastern terminus of concurrency with SR 95; now US 95 | |||

| Maricopa | Gila Bend | 119.15 | 191.75 | Northern terminus of SR 85 | |

| 120.06 | 193.22 | Western terminus of SR 84; SR 84 bypassed the US 80 Phoenix "Loop"; now I-8 Bus. east | |||

| Gila River | 142.37 | 229.12 | Gillespie Dam Bridge | ||

| Phoenix | 194.64 | 313.24 | Western terminus of concurrency with US 60/US 70/US 89 | ||

| Tempe | 202.54– 202.77 | 325.96– 326.33 | Washington Street / US 80 Alt. west – Phoenix | Interchange; US 80 Alt. was unsigned; now Center Parkway | |

| 203.32 | 327.21 | Mill Avenue Bridge over the Salt River | |||

| Mesa | 210.46 | 338.70 | Northern terminus of SR 87 | ||

| Pinal | Apache Junction | 227.14 | 365.55 | Western terminus of SR 88 | |

| Florence Junction | 243.54 | 391.94 | Eastern terminus of concurrency with US 60/US 70 | ||

| Florence | 258.00 | 415.21 | Bridge over the Gila River | ||

| 260.91 | 419.89 | Eastern terminus of SR 287 | |||

| Oracle Junction | 302.90 | 487.47 | Southern terminus of SR 77 | ||

| Pima | Tucson | 321.98 | 518.18 | Bridge over El Rillito | |

| 324.30 | 521.91 | Northern traffic circle on Oracle Boulevard; western terminus of concurrency with SR 84; now SR 77 south | |||

| 329.74 | 530.67 | Eastern terminus of concurrency with US 89/SR 84; eastern terminus of SR 84[10] | |||

| Vail | 350.69 | 564.38 | Northern terminus of SR 83 | ||

| Cienega Creek | 353.51 | 568.92 | Ciénega Bridge | ||

| Cochise | Benson | 375.79– 375.85 | 604.78– 604.87 | Interchange; western terminus of SR 86 eastern segment; SR 86 along with SR 14 in New Mexico bypassed the US 80 "Loop" to Douglas; now I-10 Bus. east | |

| St. David | 381.35 | 613.72 | Bridge over the San Pedro River | ||

| Tombstone | 396.54 | 638.17 | Eastern terminus of SR 82 | ||

| | 415.51 | 668.70 | Eastern terminus of SR 90 | ||

| Lowell | 426.04 | 685.64 | Eastern terminus of SR 92 | ||

| Douglas | 447.03 | 719.43 | Southern terminus of US 666; now US 191 north | ||

| | 497.80 | 801.13 | New Mexico state line; now NM 80 east | ||

| 1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi | |||||

Structures and attractions

The following is an incomplete list of notable attractions and structures along old US 80 in Arizona:

- Ocean to Ocean Bridge, Yuma[12]

- Ruins of Dome, Arizona[13]

- The Space Age Lodge, Gila Bend, built in 1962 and currently owned and run by Best Western[113]

- Gillespie Dam, Gila Bend[13]

- Gillespie Dam Bridge, Gila Bend, 1927 bridge across the Gila River next to the Gillespie Dam[39]

- Agua Caliente, Arizona[13]

- Arizona State Capitol, Phoenix[12]

- Tom Mix Memorial, near Florence[13]

- Tucson Inn, Tucson, part of the Miracle Mile Historic District[109]

- Stone Avenue Underpass, Tucson[13]

- Ciénega Bridge, Historic concrete arch bridge in Pima County[32]

- Horseshoe Cafe, Benson, 1940s cafe[114]

- O.K. Corral and C.S. Fly's Photo Gallery, Tombstone, site of the infamous gunfight between the Wyatt Earp, Virgil Earp, Morgan Earp and Doc Holliday against the Clantons[115]

- Queen Mine, Bisbee, a copper mine opened in the late 19th century and ceased mining operations in 1975 that is open for public tours[116]

- Gadsden Hotel, Douglas[109]

- Geronimo Surrender Monument, Douglas[109]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Shell Oil Company; H.M. Gousha Company (1951). Shell Highway Map of Arizona and New Mexico (Map). 1:1,774,080. Chicago: Shell Oil Company. Retrieved April 1, 2015 – via David Rumsey Map Collection.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 "Google Maps". Google, Inc. Retrieved September 10, 2018. - Used distance measuring tool on old US 80 segments.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Towne, Douglas (August 2018). "The "Other" Road". Phoenix Magazine. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- 1 2 Arizona State Highway Department (1935). State Highway Department Road Map of Arizona (PDF) (Map). 1:1,267,200. Cartography by W.M. DeMerse. Arizona Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Shell Oil Company; H.M. Gousha Company (1956). Shell Highway Map of Arizona (Map). 1:1,330,560. Chicago: Shell Oil Company. Retrieved March 31, 2015 – via David Rumsey Map Collection.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Jensen, Jeff (2013). Drive the Broadway of America!. Tucson: Bygone Byways. ISBN 9780978625900.

- ↑ "Notice of Public Hearing". Arizona Republic. June 24, 1958. p. 2. Retrieved August 1, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Stanhagen, W.H. (August 1939). "Washington Boulevard Alternate U.S. 80 - Arizona State Highway Department - Right of Way Maps - Maricopa County" (PDF). Existing Right of Way Plans Index - Arizona Department of Transportation. Phoenix: Arizona State Highway Department. pp. 33 to 38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Clinco, Demion (February 18, 2009). "Historic Miracle Mile: Tucson's Northern Auto Gateway" (PDF). Historic Context Study Report. Frontier Consulting. pp. 31, 32. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Arizona Department of Transportation. "ADOT Right-of-Way Resolution 1939-P-447". Arizona Department of Transportation. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ↑ Lenon, Robert (1948). Block Map of Tombstone, Arizona (Map). 1:6000. Patagonia, Arizona: Robert Lenon. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rockwood Muench, Joyce (January 1956). "Coast to Coast US 80: All-Year Scenic Southern Route" (PDF). Arizona Highways. Vol. 22, no. 1. Phoenix: Arizona State Highway Department. pp. 14–31. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Clinco, Demion (May 2016). "Historic Arizona U.S. Route 80 Historic Highway Designation Application" (PDF). Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation. p. 251. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- 1 2 Boggs, Johnny (May 23, 2016). "On the Old Gila Trail". True West Magazine. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ↑ Wrenn, Candace (September 24, 2018). "Arizona's US Route 80 Gets Historic Designation". Arizona Public Media. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Weingroff, Richard F. (October 17, 2013). "U.S. Route 80: The Dixie Overland Highway". Highway History. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Historic Arizona U.S. Route 80 Designation". Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation. August 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ↑ Corle, Edwin (1964). The Gila: River of the Southwest. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803250401. OCLC 39248974.

- ↑ Arizona Hazardous Waste Facility: Environmental Impact Statement. San Francisco: Environmental Protection Agency. January 1983. pp. L-1, L-2. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 4 "Arizona History". Office of the Arizona Governor. January 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ Broyles, Bill (2012). Last Water on the Devil's Highway: A Cultural and Natural History of Tinajas Altas. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0816598878. OCLC 873761384.

- 1 2 3 Stanley, John (February 9, 2012). "Territory of Arizona Established". Arizona Central. Phoenix. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ "The Mexican Cession". United States History. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ Hague, Harlan (December 7, 2000). "The Search for a Southern Overland Route to California". California Department of Fish and Wildlife. p. 2. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Keane, Melissa; Brides, J. Simon (May 2003). "Good Roads Everywhere" (PDF). Cultural Resource Report Report. Arizona Department of Transportation. pp. 43, 60. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ↑ McDaniel, Chris (May 29, 2011). "Ocean To Ocean Bridge critical link between shores". Yuma Sun. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- ↑ Arizona Department of Transportation. "Good Roads Everywhere: A History of Road Building in Arizona". Archived from the original on April 12, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- ↑ Laskow, Sarah (August 7, 2015). "Resurrecting the Original Road Trip on Americas' Ghost Highway". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- ↑ Fraser, Clayton B. (July 2006). "Gillespie Dam Bridge" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. pp. 14–16 – via National Park Service Santa Fe Support Office.

- ↑ Rand McNally and Company (1924). Rand McNally Auto Trails Map of Arizona and New Mexico (Map). 1:2,290,000. Chicago: Rand McNally and Company. Retrieved April 1, 2015 – via David Rumsey Map Collection.

- ↑ Rand McNally and Company (1925). Rand McNally Auto Trails Map of Arizona and New Mexico (Map). 1:1,393,920. Chicago: Rand McNally and Company. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via David Rumsey Map Collection.

- 1 2 3 Arizona Department of Transportation (October 31, 2004). "Historic Property Inventory Forms - Pima Bridges" (PDF). Inventory Records. Arizona Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- ↑ "Mule Trail Loses Out To Impatient Man". Arizona Republic. December 18, 1958. p. 37. Retrieved July 27, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Bureau of Public Roads & American Association of State Highway Officials (November 11, 1926). United States System of Highways Adopted for Uniform Marking by the American Association of State Highway Officials (Map). 1:7,000,000. Washington, DC: United States Geological Survey. OCLC 32889555. Retrieved August 23, 2016 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ↑ Arizona State Highway Department; United States Public Roads Administration (June 1939). "History of the Arizona State Highway Department" (PDF). Retrieved July 27, 2019 – via Arizona Memory Project.

- ↑ "Highway 80 Towns Will Gather Here". Arizona Daily Star. May 10, 1928. p. 27. Retrieved July 27, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Tucson's Position as Metropolis Assured by Location". Arizona Daily Star (Rodeo ed.). Tucson. February 22, 1930. p. 4. Retrieved October 29, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Historic Gillespie Dam". Gila Bend Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ Arizona State Highway Department (1928). Map of Arizona (Map). 1:1,267,200. Cartography by W.B. Land. Arizona Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via AARoads.

- 1 2 A. G. Taylor Printing Company (1930). Arizona Highway Department Condition Map of the State Highway System (Map). 1:1,267,200. Arizona State Highway Department. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via AARoads.

- ↑ Arizona Department of Transportation (October 31, 2004). "Historic Property Inventory Forms - Maricopa Bridges" (PDF). Inventory Records. Arizona Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ↑ A. G. Taylor Printing Company (1931). Arizona Highway Department Condition Map of the State Highway System (Map). 1:1,267,200. Arizona State Highway Department. Retrieved July 27, 2019 – via AARoads.

- ↑ A. G. Taylor Printing Company (1932). Arizona Highway Department Condition Map of the State Highway System (Map). 1:1,267,200. Arizona State Highway Department. Retrieved July 27, 2019 – via AARoads.

- ↑ "Arizona Briefs". Arizona Daily Star (Newspaper clipping). May 8, 1932. p. 2. Retrieved August 21, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ A. G. Taylor Printing Company (1934). Arizona Highway Department Condition Map of the State Highway System (Map). 1:1,267,200. Arizona State Highway Department. Retrieved July 27, 2019 – via AARoads.

- ↑ "Travelers Enjoy Fine Climatic Conditions On U.S. Highway 80". The Arizona Republic. Phoenix. November 20, 1938. p. 3. Retrieved October 29, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Pry, Mark; Andersen, Fred (December 2011). "Arizona Transportation History" (PDF) (Technical report). Arizona Department of Transportation. pp. 61–67. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ↑ "State Route 80: Benson to Douglas Highway and Douglas to Rodeo Highway" (PDF). Arizona's Historic Roads (PDF File). Phoenix: Arizona Department of Transportation. p. 1.

- ↑ Leighton, David (February 23, 2015). "Street Smarts: Miracle Mile's roots include fancy stores, the Mexican revolution". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ↑ "Mix Funeral to be Held in Hollywood". The New London Evening Day. October 14, 1940. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ↑ Arizona State Highway Department (1946). State Highway Department Road Map of Arizona (Map). 1:1,267,200. Cartography by W.M. DeMerse. Arizona Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via AARoads.

- ↑ "Fight For Tourist Travel on U.S. 80". Tucson Daily Citizen. April 15, 1947. p. 2. Retrieved October 29, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ McNeil, Blanche (June 9, 1949). "Chamber of Commerce Comments". The Casa Grande Dispatch. Tucson Chamber of Commerce. p. 6. Retrieved October 31, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Highway 80 Maps Will Be Given To Travelers". Arizona Daily Star. Tucson. November 2, 1949. p. 1B. Retrieved June 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ McPhee, John C. (August 8, 1954). "Lavender Pit Story". Days and Ways section. Arizona Republic. Further details provided by the A.J. Gilbert Construction Company. Phoenix. pp. 6–10. Retrieved June 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Plans for Bridge at Yuma Get Approval of Merchants". Arizona Daily Star. Tucson. May 8, 1954. p. 4A. Retrieved June 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Road Rerouted For New Bridge". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. June 24, 1954. p. 32. Retrieved June 6, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Four-Lane Bridge Over Colorado To Be Built". Arizona Daily Star. Tucson. October 27, 1954. p. 14A. Retrieved June 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Yuma Bridge Construction on Schedule". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. November 6, 1955. §2, p. 4. Retrieved June 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "2 States Dedicate New Yuma Bridge". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. Associated Press. May 14, 1956. p. 4. Retrieved June 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Roth, Bernie (April 8, 1955). "Cienega Wash No Longer Holds Terrors For Unwary Motorist". Arizona Daily Star (Morning ed.). Tucson. p. 1B. Retrieved June 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Route 80 Safety Tested On Double Center Stripe". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. September 3, 1956. p. 3. Retrieved June 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Fischer, Howard (October 17, 2017). "Jefferson Davis Highway 'no longer exists' in Arizona — but its marker will stay". Arizona Daily Star. Tucson. Capitol Media Services. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- 1 2 "$2 Million Contract Let For Cochise Road Job". Arizona Daily Star. Tucson. November 26, 1956. p. 2A. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspaper.com.

- 1 2 3 "Bypass Job Speeded". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. Associated Press. March 9, 1959. p. 9. Retrieved June 13, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Mule Trail Loses Out To Imaptient Man". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. December 18, 1958. p. 37. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 Harelson, Hugh (June 1, 1958). "Bisbee Bets on $2 Million Tunnel to End Town's Copper Doldrums". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. p. 1. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Bisbee Tunnel Study Ready". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. April 1, 1955. p. 16. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Bids Opened For Tunnel At Bisbee". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. November 14, 1956. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Mule Pass Tunnel's Validity To Be Taken To High Court". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. January 31, 1957. p. 15. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "State Files Suit To Test Mule Pass Road Contract". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. February 8, 1957. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Mule Pass Tunnel Contract Valid, Supreme Court Rules". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. March 6, 1957. p. 2. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspaper.com.

- 1 2 "Workers Near Break-Through In Spectacular Tunnel Bore". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. October 6, 1957. §S, p. 10. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Drilling Crew Sets Record In Cochise". Arizona Daily Star. Tucson. September 28, 1957. p. 5A. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "U.S. 80 Tunnel Breaks Through". Tucson Daily Citizen (Evening ed.). October 30, 1957. p. 28. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 Harelson, Hugh (December 14, 1958). "State's Longest Highway Tunnel At Mule Pass Will Open Friday With Dedication Ceremonies". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. §3, p. 16. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Date Of New Tunnel Dedication Changed". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. November 27, 1958. p. 32. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Beene, Wallace (December 19, 1958). "$2 Million Mule Pass Bore Opened At Dedication Rites". Tucson Daily Citizen (Evening ed.). p. 2. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Bisbee Would Save Old 'Glory Hole'". Arizona Daily Star (Morning ed.). Tucson. April 15, 1960. p. 3A. Retrieved June 13, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Road Work Won't Injure Buildings". Arizona Daily Star (Morning ed.). Tucson. April 9, 1960. p. 6A. Retrieved June 13, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Road Ahead Of Schedule". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. Associated Press. January 14, 1961. p. 6. Retrieved June 13, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Sinking Section Reported In New Bisbee Freeway". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. September 15, 1961. p. 62. Retrieved June 13, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Bisbee Citizens, Highway Department Officials Dedicate Freeway Into City". Arizona Daily Star. Tucson. October 1, 1961. p. 11A. Retrieved June 13, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Public Roads Administration (August 14, 1957). Official Route Numbering for the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways as Adopted by the American Association of State Highway Officials (Map). Scale not given. Washington, DC: Public Roads Administration. Retrieved April 4, 2012 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ↑ Arizona State Highway Department (November 5, 1948). "ADOT Right-of-Way Resolution 1948-P-065". Retrieved September 7, 2018 – via Arizona Highway Data.

Concstruct portion of highway from jct. S.R. 84 in Sec. 27, T13S, R13E S to Sec. 25, T13S, R13E.

- ↑ "Contract For Freeway To Be Awarded Today". Arizona Daily Star. Tucson. November 10, 1950. p. 26. Retrieved June 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Tucson: Day-by-Day in 1950". Arizona Daily Star (Morning ed.). Tucson. December 31, 1950. p. 22. Retrieved June 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Inskeep, Lester (May 27, 1951). "Historic Santa Cruz River Had to Bow to Tucson's Freeway". Arizona Daily Star (Morning ed.). Tucson. p. 14. Retrieved June 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Inskeep, Lester (December 21, 1951). "Traffic Crush Forces Freeway to Open Ahead of Schedule". Arizona Daily Star (Morning ed.). Tucson. p. 1A. Retrieved June 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Commission to Decide on Hauling Requests". Arizona Daily Star. Tucson. March 9, 1952. p. 10C. Retrieved June 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "State To Hold First Superhighway Hearing Under New U.S. Law Dec. 6". The Arizona Republic. Phoenix. Associated Press. November 16, 1956. p. 21. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- 1 2 "Federally Aided Road Improvements Begin". Arizona Daily Star (Morning ed.). Tucson. March 26, 1957. p. 1. Retrieved October 6, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 Harelson, Hugh (April 12, 1960). "$3 Million Road Budget Explained". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. p. 17. Retrieved October 7, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Rand McNally & Co. (1958). State Highway Department Road Map of Arizona (Map). 1:1,520,640. Arizona State Highway Department. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via AARoads.

- ↑ Cole, Ben (May 1, 1963). "State Road Jobs Eyed By House". Arizona Republic. Phoenix. pp. 1, 4. Retrieved June 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Rand McNally & Co. (1963). State Highway Department Road Map of Arizona (Map). 1:1,584,640. Arizona State Highway Department. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via AARoads.

- ↑ Photogrammetry and Mapping Division (1971). State Highway Department Road Map of Arizona (Map). 1:1,267,200. Arizona State Highway Department. Retrieved August 24, 2018 – via AARoads.

- ↑ Arizona Department of Transportation (September 16, 1977). "ADOT Right-of-Way Resolution 1977-16-A-048". Retrieved October 20, 2019 – via Arizona Highway Data.

Remove U.S. 80 designation from California state line to jct. I-10 in Benson.

- ↑ "U.S. 80 all but gives way to Interstate highways". Arizona Daily Star (Final ed.). Tucson. Associated Press. December 27, 1977. p. 6C. Retrieved June 13, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Arizona Department of Transportation (September 16, 1977). "ADOT Right-of-Way Resolution 1977-16-A-048". Retrieved October 20, 2019 – via Arizona Highway Data.

Delete U.S. 80 designation from California state line to jct. I-10 in Benson. Renumber S.R. 85 in Gila Bend to jct. B-10 in Phoenix.

- ↑ Arizona Department of Transportation. "ADOT Right-of-Way Resolution 1989-12-A-096". Arizona Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ↑ Toll, Eric J. (November 2, 2015). "Interstate 10 completed; I-11 construction begins". Phoenix Business Journal. Retrieved August 24, 2018.