| Saint Mark's Basilica | |

|---|---|

| |

Location within Greece | |

| General information | |

| Status | Art gallery |

| Type | Church |

| Location | Heraklion, Crete |

| Country | Greece |

| Coordinates | 35°20′21″N 25°8′1″E / 35.33917°N 25.13361°E |

| Completed | 1239 |

| Inaugurated | 1960 |

The Basilica of Saint Mark (Greek: Βασιλική του Αγίου Μάρκου, Italian: Basilica di San Marco), also known as Hagios Markos (Greek: Άγιος Μάρκος), is a former Roman Catholic church in the center of the city of Heraklion, Crete, in the Eleftheriou Venizelou Square. It was built during the Venetian rule of the island in 1239, primarily used by the local lords and officials of the island. After the Ottoman conquest of Crete in 1669, it was converted into a mosque with the name Defterdar Ahmet Pasha Mosque (Greek: Δεφτερδάρ Αχμέτ Πασά Τζαμί, Turkish: Defterdar Ahmet Paşa Camii), and remained so until 1915. The building was restored after 1956 and ever since functions as a public art gallery.[1] It is one of the few Roman Catholic churches still standing in Cretan cities and towns.[2] Architecturally-wise it is a three-aisled basilica church with an elevated central nave. It has a portico in its entrance in the western façade.

History

Venetian period

The basilica of Saint Mark was built in 1239, after the Venetian conquest of Crete following the Fourth Crusade, with the first stone put in place by the Latin bishop of Ierapetra.[3] It was built in Gothic style, in accordance to the Western churches and highlighting the difference of the Latin dogma.[4] It was built in the center of the city of Candia (modern Heraklion), the capital of Crete, across the palace of the Duke of Candia, and was used by the duke and high-ranking officials of the local commune for their needs. The church belonged not to the Latin bishop but to the duke himself, who appointed a prefect or a "chaplain" in charge of the church. The ducal degrees were announced in the entrance of the basilica, which was also the place were the official assumptions of the lords and officials' duties took place.[5] The members of the duke's family were buried in the church's yard.[3]

The first church was severely damaged in the 1303 Crete earthquake, but it was later restored. A stronger still earthquake which hit the island in 1508 damaged Saint Mark anew. In a report dating to 1552 it is mentioned that the northern wall was about to collapse, and thus it was supported with four struts, two of which survive to this day. In a document from 1514 the local duke asked for wooden beams to be transferred from the town of Sfakia for the repair works of the basilica. Those works were completed in 1557, but Saint Mark was once more partially ruined following earthquakes in 1564 and 1595. Renovation works on the church took place in 1599 with the builder Micheles Raptopoulos and the carpenter Giannis Kladas in charge, though after an autopsy in 1625 the northern wall was deemed again to be about to collapse.[6]

During the Cretan War (1645–1669), the bell tower of the basilica was used as an observatory, with its bells ringing every time the bombardment started.[7] Saint Mark's bell tower was different from the others in the city due to its top that was flat and battlemented and also had a clock.[8] After the surrender of Candia to the Ottomans, the Venetians took the bells and other relics away.[7]

Ottoman period

After the fall of Candia in 1669, the building was surrendered to Ahmet Pasha, who was the Ottoman defterdar (the minister of finance) from 1661/2 until 1675.[9] Ahmet Pasha converted the Catholic church into a mosque and bought some buildings of the city, including the duke's palace, in order to fund the mosque. The Ottomans demolished the bell tower of Saint Mark and in its place they erected a minaret, while also destroying the murals and frescoes in the interior of the church and throwing away the bone relics to build a mihrab and the minbar. The mosque was named after its founder, Defterdar Ahmet Pasha. It would remain as a mosque for over two centuries until 1915, when it was closed by the Greek state.[7]

The Ottoman traveller Evliya Çelebi visited Crete in 1669 and wrote that the basilica was situated in the market of Candia, with its façade facing the fountain square (the Fountain of Morosini), and that it was founded by the sultan Mansur in the times of Caliph Umar, an invented story that provided impeccable Islamic pedigree for one of the city's main public buildings. He also wrote that a yard could be found north of the building, and that faucets had been built on the northern wall. The mosque had in total three yards to the north, the south and the east, a well and a cistern. Its minaret was built on the south corner of the basilica, and its remains can still be seen to this day. The mosque complex (Külliye) also consisted of three shops, a cellar and a two-storey building.[9]

For the maintenance and operation of the new mosque there was a waqf (endowment) which consisted of nine houses, two monastic complexes, twenty-two shops and two farms. Of these, six houses and one monastic complex was situated in the Christos Kefalas district of the city, one house and one farm in the Agros Kefalas district, one house and seventeen shops in the Saint Kyriake district, one house, one monastic complex and one farm in the Archistrategos district, and finally five shops in the John Chrysostom district. According to the account of the kadi of Candia in 1688 it is mentioned that the waqf of the mosque also maintained a türbe outside the city walls.[9]

Renovation works took place in 1706, which cost 1,034 kuruş. A new request for new renovation works was made in 1761, which is estimated to have cost 18,287 para.[9]

Modern period

After the Greco-Turkish population exchange in 1924 and the departure of the island's Muslim community, the former mosque came to the hands of the National Bank of Greece, and then to the municipality of Heraklion,[7] and was used at first as a cinema.[6] The minaret was finally torn down in 1924.[10] In 1949 the Section Tourism Committee of Heraklion (STCH) suggested to fund the renovation of the church along with that of other monuments of the city.[11] In the early 1950s the municipal council suggested that the church be demolished and a municipal theatre or a post office be built in its place, a plan which was abandoned as the necessary funds could not be collected.[12] In 1954 the archaeological council decided on the preservation of the church and in 1956 restoration works of the basilica began by the Society of Cretan History Studies.[13] This was the oldest restoration for a monument of Western architecture that took place in Crete.[14] This basilica is one of the few Roman Catholic churches that still stand on the island of Crete.[2]

During the restoration, the middle aisle was elevated in order for it to return to its original place, with the addition of pointed windows on its sides, twelve on each side. Additionally various openings that had been created in the side walls of the church were closed off again, five pointed windows were added on the north wall, in correspondence with the south, the portico was reconstructed, the floor of the church was covered with new slabs, new plastering was made, the bases of the inner colonnade and the metal glazing in the windows were repaired, and finally doors were constructed while the building was reinforced with concrete.[15]

Ever since the completion of the restoration works in 1960,[16] the former church has been used as a municipal art gallery.[1] In 1961 it hosted the first international conference on Cretan studies, held under the auspices of the Society of Cretan History Studies.[17] It houses exhibits of works of art, most notably the Domenikos Theotocopoulos exhibit in 1990, the Cretan School exhibit in 1998 and the Fayum mummy portraits exhibit also in 1998, which were followed by international conferences. Several Greek artists have exhibited their works in the gallery, such as Maria Fioraki, Lefteris Kanakakis, Thomas Fanourakis, Georgios Georgiades, and Lilian Manolakaki among others.[18]

Architecture

The church building

Saint Mark is a three-aisled basilica type of church. On the interior, its dimensions are 32 x 15,6 metres in the south and west side, while the north and east sides are longer by thirty centimetres. Kostas Lassithiotakis has theorized that this asymmetry is due to the various reconstructions of the northern wall.[19] The central aisle is the widest, with a width of 6,6 m., while the southern is 4,6 m. wide and the northern 4,4.[20] The elongated proportions of the aisles greatly emphasize the elongated dimensions of the basilica.[21] Its axis is tilted toward the south by 25 degrees in relation to its west-east axis.[19] The church contains no niche on its eastern wall.[22]

Its roof is made of wood and it is tripartite one, with the central part protruding above the other two, which is the shape in which it is depicted by Georgios Corner in 1625. During the Ottoman period the church-mosque was remodeled, with the roof getting a double-edged shape. During the restoration works of the mid 1900s, the roof was returned to its original design, with the central aisle being elevated with the use of concrete slab. The floor is made up of rectangular plates and local stone. The church's central gate has a straight lintel and a relief arch. On the southern wall five sharp-pointed windows are preserved, which date back to the church's original construction.[23] The windows on the northern wall were constructed during the 1956 renovation works, as were the twenty-four in total windows on the side walls of the central aisle.[24]

The ornate doorway of the Venetian palace of Ittar has been transferred to the interior of the church, which has been integrated into the inner side of the northern entrance of the church.[25] In the south internal wall of Saint Mark a three-lobed window of Gothic style has been installed, originating from some unknown building. It has three sharp-pointed openings, with the central one being the tallest, and all are within the sharp-pointed arch. It consists of well-hewn white stones.[16] In the past, there used to be multiple doors in both the south and the north walls, but in time they were blocked.[24] In its interior the church used to be decorated with Byzantine murals, which only surfaced after the restoration works took place.[23]

On the southwest corner of the basilica the base of the old bell tower can still be seen, made of square hewn stones 4,2 metres tall, as well as the remnants of the demolished minaret on top of it.[10]

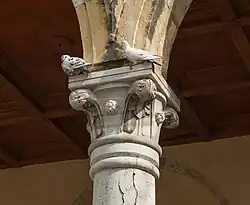

The columns

The aisles are separated from one another by two rows of columns consisting each of five columns made of green granite which support six Gohic arches. The columns are each a different height. Their capitals also differ from one another, though they are all gilt. Four of those in the northern side are simple basket-shaped, while the easternmost is of Gothic fluted style,[20] as is its equivalent on the easternmost column of the southern colonnade. The fluted capitals are dated to the fourteenth century. A fluted capital is used as the column base.[23] The bases of the columns are also dissimilar, as they are made of stone and covered externally by mortar which has a decorative leaf design.[20]

It is not entirely known why the columns are not all the same size. A theory holds that each column originates from different, older buildings and were all together incorporated in Saint Mark later. Kostas Lassithiotakis suggests that it is most plausible that the different columns is the result of all the different restoration works that ever took place in Saint Mark, with some columns dating from the original constructions and other from later repair works, which would have included restructuring the interior of the basilica for the sake of stability. He also says that in a ducal report of 1552, the church is said to have eight arches, but now it has twelve.[20] It is possible that the extra arches are from Greco-Roman monuments from the Heracleium and Knossos archaeological sites.[6]

Portico

The building sports a portico with a colonnade in its entrance in the western façade, commonly known as Saint Mark's Loggia. The columns used to support five arches, which in turn supported a flat roof.[8] The central arch is the largest one, with an opening of 3,83 metres. It is wider than those surrounding it by a metre.[22] The portico is 6,15 metres long.[26]

Kostas Lassithiotakis notes that medieval Italian churches rarely sported porticos and based on the Renaissance style of Saint Mark's portico, it cannot be dated to the original construction of the church, but rather it was added much later.[22] The loggia was used by merchants who sold grain on counters. During the Ottoman period the flat roof was removed and a pitched roof was added, which rested directly on the columns. Of the original columns, only three survive, with their capitals dating to around the fourteenth century.[8]

During the renovation works of the former church there were attempts for the portico to be restored to its original form. A reinforced concrete slab was used for the roof, which was covered internally with wooden beams which form rectangular panels. Renaissance-style reliefs were placed on the cornice and the arches.[24]

Gallery

- Basilica of Saint Mark

Close-up of the portico.

Close-up of the portico. Old photo of the columns.

Old photo of the columns. Interior of the gallery.

Interior of the gallery. Old photo.

Old photo.

See also

- Church of Saint Nicholas, Chania, another Catholic church in Crete.

- Catholic Church in Greece

- Kingdom of Candia

- List of former mosques in Greece

References

- 1 2 "Ναός του Αγίου Μάρκου". www.heraklion.gr (in Greek). Δήμος Ηρακλείου. Retrieved 2019-10-14.

- 1 2 Gratziou 2010, p. 27

- 1 2 Alexiou & Lassithiotakis 1958, p. 11

- ↑ Georgopoulou 2001, pp. 171–172

- ↑ Gerola 1908, p. 17

- 1 2 3 Alexiou & Lassithiotakis 1958, p. 13

- 1 2 3 4 Alexiou & Lassithiotakis 1958, p. 12

- 1 2 3 Alexiou & Lassithiotakis 1958, p. 15

- 1 2 3 4 "Τζαμί του ντεφτερντάρ Αχμέτ Πασά στο Χάνδακα". digitalcrete.ims.forth.gr. Archived from the original on 2019-10-20. Retrieved 2019-10-14.

- 1 2 Alexiou & Lassithiotakis 1958, p. 21

- ↑ Dimanopoulos 2015, p. 115

- ↑ Dimanopoulos 2015, pp. 119–120

- ↑ Dimanopoulos 2015, p. 121

- ↑ Gratziou 2010, p. 15

- ↑ Alexiou & Lassithiotakis 1958, pp. 21–23

- 1 2 Gratziou 2010, p. 55

- ↑ "Το Β' Διεθνές Κρητολογικό Συνέδριο". www.kathimerini.gr. Η Καθημερινή. September 30, 2001. Retrieved 2019-10-21.

- ↑ "Δημοτική Πινακοθήκη". www.heraklion.gr. Δήμος Ηρακλείου. Archived from the original on 2016-09-10. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- 1 2 Alexiou & Lassithiotakis 1958, p. 18

- 1 2 3 4 Alexiou & Lassithiotakis 1958, p. 19

- ↑ Gratziou 2010, p. 186

- 1 2 3 Alexiou & Lassithiotakis 1958, p. 20

- 1 2 3 Alexiou & Lassithiotakis 1958, p. 14

- 1 2 3 Alexiou & Lassithiotakis 1958, p. 22

- ↑ Gratziou 2010, p. 73

- ↑ Panagopoulos 1979, p. 140

Bibliography

- Alexiou, Stylianos; Lassithiotakis, Konstantinos (1958). Η αποκατάστασις του ναού του Αγίου Μάρκου του Χάνδακος. Εταιρία Κρητικών Ιστορικών Μελετών.

- Georgopoulou, Maria (2001). "Οι γοτθικές εκκλησίες του Αγίου Μάρκου στις αποικίες της Βενετίας". Θ΄ ΔΙΕΘΝΕΣ ΚΡΗΤΟΛΟΓΙΚΟ ΣΥΝΕΔΡΙΟ Ελούντα, 1-6 Οκτωβρίου 2001 Περιλήψεις Επιστημονικών Ανακοινώσεων. Εταιρεία Κρητικών Ιστορικών Μελετών. ISBN 978-960-86721-2-3.

- Gerola, Giuseppe (1908). Monumenti Veneti nell' isola di Creta /ricerche e descrizione fatte dal dottor Giuseppe Gerola per incarico del R. Istituto (in Italian). Venice: R. Instituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti.

- Gratziou, Olga (2010). Η Κρήτη στην ύστερη μεσαιωνική εποχή: Η μαρτυρία της εκκλησιαστικής αρχιτεκτονικής. Heraklion: Πανεπιστημιακές Εκδόσεις Κρήτης. ISBN 978-960-524-301-2.

- Dimanopoulos, Spyros (2015). "Αστικός χώρος, κοινωνικά υποκείμενα και τουριστική ανάπτυξη. Η περίπτωση του Ηρακλείου, 1945-1960". Μνήμων. 34: 97–124. doi:10.12681/mnimon.10174. ISSN 2241-7524.

- Panagopoulos, Beata Maria (1979). Cistercian and mendicant monasteries in medieval Greece. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-64544-4.

External links

- Heraklion Art Gallery official site

Media related to Saint Mark's Basilica, Heraklion at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Saint Mark's Basilica, Heraklion at Wikimedia Commons

.jpg.webp)