| Department of Education | |

|---|---|

| Minister of Education | Michelle McIlveen MLA |

| National education budget (2021–2022) | |

| Budget | £2.3 billion |

| General details | |

| Primary languages | English, Irish |

| System type | Regional |

| Compulsory education | 1831 |

| Literacy (2003[1]) | |

| Total | 99% |

| Male | 99% |

| Female | 99% |

| Life in Ireland |

|---|

| Culture |

| Economy |

| General |

| Society |

| Politics |

| Policies |

The education system in Northern Ireland differs from elsewhere in the United Kingdom (although it is relatively similar to Wales), but is similar to the Republic of Ireland in sharing in the development of the national school system and serving a similar society with a relatively rural population. A child's age on 1 July determines the point of entry into the relevant stage of education in the region, whereas the relevant date in England and Wales is 1 September.[2]

Overview

As with the island of Ireland as a whole, Northern Ireland has one of the youngest populations in Europe and, among the four UK nations, it has the highest proportion of children aged under 16 years (21% in mid-2019).[3]

In the most recent full academic year (2021–2022), the region's school education system comprised 1,124 schools (of all types) and around 346,000 pupils, including:

- 796 primary schools with 172,000 pupils;

- 192 post-primary schools with 152,000 pupils;

- 126 non-grammar post-primary schools with 86,000 pupils;

- 66 grammar schools with 65,000 pupils;

- 94 nursery schools with 5,800 pupils;

- 39 special schools with 6,600 pupils (specifically for children with special educational needs); and

- 14 independent schools with 700 children.[4]

Enrolments in further and higher education were as follows (in 2019–2020) before disruption to enrolments and classes caused by the COVID-19 pandemic:

- six regional further education colleges with 132,000 students;

- two universities – Queen's University Belfast and Ulster University – with 53,000 students;

- two teacher training colleges – Stranmillis University College and St Mary's University College, Belfast – with 2,200 students;

- the College of Agriculture, Food and Rural Enterprise with 1,700 students on three campuses; and

- the Open University with 4,200 students.[5][6][7]

Statistics on education in Northern Ireland are published by the Department of Education and the Department for the Economy.

History

The first state-funded educational institutions in Ireland were established in the 16th century. The first printing press in Ireland was established in 1551,[8] the first Irish-language book was printed in 1571 and Trinity College, Dublin (TCD), was established in 1592.[9]

The Education Act 1695 prohibited Irish Catholics from running Catholic schools in Ireland or seeking a Catholic education abroad, until its repeal in 1782.[10] As a result, highly-informal secret operations that met in private homes were established, called "hedge schools."[11] Historians generally agree that hedge schools provided a kind of schooling, occasionally at a high level, for up to 400,000 students in 9000 schools, by the mid-1820s.[12] J. R. R. Adams says the hedge schools testified "to the strong desire of ordinary Irish people to see their children receive some sort of education." Antonia McManus argues that there "can be little doubt that Irish parents set a high value on a Hedge school education and made enormous sacrifices to secure it for their children....[the Hedge schoolteacher was] one of their own".[13] The 1782 repeal of the 1695 penal laws had made the Hedge schools legal, although still not in receipt of funding from the Parliament of Ireland.

Formal schools for Catholics under trained teachers began to appear after 1800. Edmund Ignatius Rice (1762–1844) founded two religious institutes of religious brothers: the Congregation of Christian Brothers and the Presentation Brothers. They opened numerous schools, which were visible, legal, and standardised. Discipline was notably strict.[14]

From 1811, the Society for the Promotion of the Education of the Poor of Ireland (Kildare Place Society), started to established a nationwide network of non-profit, non-denominational schools, in part funded through the production and sales of textbooks.[15] By 1831, they were operating 1,621 primary schools, and educating approximately 140,000 pupils.[16]

In 1831, the Stanley letter led to the establishment of the Board of National Education and the National School system using public money. The UK Government appointed the commissioner of national education whose task was to assist in funding primary school construction, teacher training, the producing of textbooks, and funding of teachers.[15]

After the partition of Ireland in 1922, the education systems of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland became separate.

Administration

Education is devolved to the Northern Ireland Assembly and the government departments which are mainly responsible for education policy are assigned responsibilities according to the different levels of the education system. The Department of Education is responsible for pre-school, primary, post-primary and special education, youth work policy, the promotion of good community relations within and between schools, and teacher education and salaries. Further and higher education sits within the remit of the Department for the Economy and the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs as young people and adults at that stage are either employed or being prepared for entering employment.

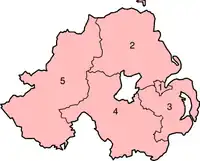

The Education Authority (EA) is responsible for ensuring that nursery, primary and post-primary education services are available to meet the needs of children and young people and for providing support for youth services. The authority was established in 2015 and its services, in relation to education, were previously delivered by the five education and library boards (ELBs) from the 1970s onwards and by county councils before that time. Each of the former ELBs is now a sub-region of the Education Authority:

| Sub region of the Education Authority | Area covered | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Belfast (formerly BELB) |  | |

| 2. | North Eastern (formerly NEELB) | Antrim, Ballymena, Ballymoney, Carrickfergus, Coleraine, Larne, Magherafelt, Moyle, Newtownabbey | |

| 3. | South Eastern (formerly SEELB) | Ards, Castlereagh, Down, Lisburn and North Down | |

| 4. | Southern (formerly SELB) | Armagh, Banbridge, Cookstown, Craigavon, Dungannon and South Tyrone, Newry and Mourne | |

| 5. | Western (formerly WELB) | Derry, Fermanagh, Limavady, Omagh, Strabane | |

Curriculum

The majority of examinations sat, and education plans followed, in Northern Irish schools are set by the Council for the Curriculum, Examinations & Assessment. All schools in Northern Ireland follow the Northern Ireland Curriculum which is based on the National Curriculum used in England and Wales. At age 11, on entering secondary education, all pupils study a broad base of subjects from the nine 'Areas of Learning':[17][18] Language and Literacy, Mathematics and Numeracy, Modern Languages, The Arts, Environment and Society, Science and Technology, Learning for Life and Work, Physical Education, and Religious Education.

| Area of Learning | Compulsory subjects strands |

|---|---|

| Language and Literacy | English,Irish,[lower-alpha 1]Media Education |

| Mathematics and Numeracy | Mathematics, Financial Capability |

| Modern Languages | An official language of the EU[lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3] |

| The Arts | Art and Design, Drama, Music |

| Environment and Society | History, Geography |

| Science and Technology | Science, Technology and Design |

| Learning for Life and Work | Employability, Home Economics, Local and Global Citizenship, Personal Development |

| Physical Education | Physical Education |

| Religious Education | Religious Education |

| Non-compulsory subjects offered in some schools | ICT A second official language of the European Union[lower-alpha 3] Arabic,[19] Latin, Mandarin Chinese[20] or another non-EU language |

At age 14, pupils select which subjects to continue to study for General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) examinations. Currently, it is compulsory to study English Language and Mathematics, although subjects such as English Literature, French, Learning for Life and Work, Religious Studies and Science (single-, double- or triple-award) may also be compulsory in certain schools. In addition, pupils usually choose to continue with other subjects and many study for eight or nine GCSEs, and possibly up to ten or eleven. GCSEs mark the end of compulsory education in Northern Ireland.

At age 16, some pupils stay at school and choose to study A-Level – AS and A2 – level subjects or more vocational qualifications such as Applied Advanced Levels; many also take up vocational courses at further education colleges on leaving school. Those choosing AS and A2 levels normally pick three or four subjects and success in these can determine acceptance into higher education courses at university.

Levels of education

Pre-primary education is optional in Northern Ireland with preschool stage for children aged 3 and 4. In some pre-schools, pupils can leave when they turn 4 and enter into an optional Reception class in their local primary school. (This is entirely optional in most schools which provide these classes.)

Primary education covers three stages – Foundation, Key Stage 1, and Key Stage 2.

- Foundation Stage

- Reception, age 4 (optional; see above note)

- Primary 1, age 4 to 5 (equivalent to Reception in England and Wales)

- Primary 2, age 5 to 6

- Key Stage 1

- Primary 3, age 6 to 7

- Primary 4, age 7 to 8

- Key Stage 2

- Primary 5, age 8 to 9

- Primary 6, age 9 to 10

- Primary 7, age 10 to 11

Post-primary (or secondary) education covers up to three stages – Key Stage 3, Key Stage 4, and Key Stage 5:

- Key Stage 3

- Year 8, age 11 to 12 (equivalent to Year 7 in England and Wales)

- Year 9, age 12 to 13

- Year 10, age 13 to 14

- Key Stage 4

- Year 11, age 14 to 15

- Year 12, age 15 to 16 (including GCSE examinations)

- Key Stage 5

Although the Department of Education uses Year 8 to Year 14 for post-primary education, the traditional First to Fifth Form, Lower Sixth and Upper Sixth are still used, at least informally, by some schools. Young people may continue their education at a post-primary school (often a grammar school) or at a further education college after Key Stage 4. A range of tertiary education qualifications are available through further education colleges, universities and other institutions, including at bachelor's degree, master's degree and doctorate levels.

Post-primary transfer

Most primary school children will transfer to non-grammar post-primary schools. However, issues around post-primary transfer and academic selection receive a high level of media coverage, as many parents regard a place for their child in a grammar school as a form of social mobility. In 2021–2022, 57% of young people in post-primary education (87,000 pupils) attended non-grammar schools and 43% attended grammar schools (65,000 pupils).[4]

The Education Act (Northern Ireland) 1947 introduced a school system which included a government-run eleven-plus post-primary transfer test as an entrance exam for grammar schools; this had previously been introduced in England and Wales in 1944. The test, a form of academic selection, was retained in Northern Ireland whereas England and Wales moved towards a comprehensive school system, which is also in place in Scotland. The differences in political opinion regarding academic selection, with unionists generally in favour and nationalists and the Alliance Party broadly opposed, reflect differences between Conservative and Labour in Great Britain; a Conservative government introduced the eleven-plus in the 1940s and a Labour government introduced comprehensive schooling in the 1970s.

As Minister of Education in the first Northern Ireland Assembly after the Good Friday Agreement, Martin McGuinness commissioned a review of post-primary transfer – the Burns report – which (in 2001) proposed the ending of the eleven-plus (and academic selection in post-primary transfer) and a system of formative assessment through a pupil profile to provide a wider range of educational information to teachers, parents and pupils. In the subsequent public consultation, a majority of respondents favoured the abolition of eleven-plus tests, but not the end of academic selection, and most wanted all schools to use the same criteria for entry with parental preference to be the most important criterion.

The Assembly was suspended in November 2002 and, under direct rule, Education Minister Jane Kennedy commissioned a post-primary transfer working group, chaired by Steve Costello, which reported in 2004 and broadly supported the Burns Report and recommended a broader curriculum through a model known as the entitlement framework. The Assembly was restored in March 2007 and then Education Minister Caitríona Ruane reaffirmed the decision by her predecessors to abolish the eleven-plus; the last government-run test took place in 2008. The majority of grammar schools, however, decided to set their own entrance exams which, at present, are available in two types – AQE and GL Assessment – although a single test is planned from 2023 onwards.[21]

School sectors by ethos

Controlled

Controlled schools are so-called as their governance is controlled by the state (e.g. through the Education Authority as the employer of teachers) although schools are managed by their board of governors, which include representatives of parents, teachers and transferor churches (who transferred their control of schools to the state in the mid-20th century). Controlled schools are open to children of all faiths and none.

Many controlled schools were originally church schools – under the management of the Church of Ireland, Presbyterian Church in Ireland and Methodist Church in Ireland – whose control was transferred in the 1930s and 1940s in return for assurances that a Christian ethos would continue through collective worship (school assemblies), the teaching of non-denominational religious education, and representation of churches on boards of governors. The three churches have a role in education through the Transferor Representatives' Council (TRC) and nominate around 1,500 school governors to the boards of controlled schools. In a more recent development, controlled integrated schools are those which have opted for a formally integrated status and therefore form part of both the controlled and integrated schools sectors.

The Education Act 2014,[22] which created the Education Authority in the following year, was accompanied by a commitment by the Education Minister and the Northern Ireland Executive to establish and fund a support body for schools in the controlled sector. The Controlled Schools' Support Council (CSSC) therefore became operational in 2016; its headquarters are in Stranmillis University College, Belfast. Membership of the council is voluntary and over 90% of controlled schools are members of the CSSC.

In 2021–2022, there were 379 primary schools, 63 nursery schools, 53 secondary (non-grammar) schools and 16 grammar schools in the controlled sector – a total of 511 schools. These included 24 controlled integrated primary schools, five secondary schools and one nursery school with controlled integrated status, and two Irish medium schools. Around 147,000 pupils attended controlled schools (including 8,000 in controlled integrated schools), representing approximately 42% of all pupils in Northern Ireland. In terms of religious breakdown, 59% of pupils in controlled schools were Protestant, 11% were Catholic, and 30% were from other backgrounds.[4]

Catholic maintained

Catholic maintained schools have a Roman Catholic ethos and are maintained by state funding, although the Council for Catholic Maintained Schools (CCMS) – established through the Education Reform (Northern Ireland) Order 1989 – employs teachers in the sector as well as representing its interests. The membership of the CCMS includes representatives of the Department of Education, trustees (Catholic bishops in Northern Ireland), parents (drawn from the local community on a voluntary basis) and teachers. The Catholic Schools' Trustee Service (CTSS) provides teachers, clergy and others interested in Catholic education with resources, guidance and policies to assist them in their work, and highlights the Catholic ethos in education in both the maintained and voluntary grammar sectors.

In 2021–2022, there were 442 Catholic maintained schools – 355 primary schools, 56 post-primary (non-grammar) schools, and 31 nursery schools – with a total of 124,000 pupils, representing around 35% of all pupils; 93% of pupils in the sector were from a Catholic background.[4]

Voluntary grammar

Voluntary grammar schools are self-governing schools and generally of long standing, having originally established to provide an academic education at post primary level on a fee-paying basis. These schools are now funded by the Department and managed by boards of governors which are constituted in accordance with each school's scheme of management – usually representatives of foundation governors, parents, and teachers and in most cases, representatives of the department or the Education Authority. The board of governors is the employing authority and is responsible for the employment of all staff in its school.

There were 50 voluntary grammar schools in 2021–2022 with around 51,000 pupils. The sector included 29 schools under Catholic management with 30,000 pupils and 21 under other forms of management with 21,000 pupils; 95% of pupils attending Catholic voluntary schools are from a Catholic background and 57% of pupils attending other voluntary schools are from a Protestant background.[4] The Governing Bodies Association represents the interests of voluntary grammar schools.

Integrated

Grant-maintained integrated schools are those which have been established by the voluntary efforts of parents (such as the first formally integrated school, Lagan College, which was founded in 1981). Controlled integrated schools are controlled schools which have opted to have integrated status following a transformation process with the approval of parents. While parents, rather than churches, took the initiative in the development of grant-maintained integrated schools, the older controlled integrated schools (for example, those built in the 1930s and 1940s) were founded by Protestant churches before their transfer to the state in the mid-20th century.[23]

The Northern Ireland Council for Integrated Education (NICIE), a voluntary organisation, promotes, develops and supports integrated education, through the medium of English. The Integrated Education Fund (IEF) is a trust fund for the development and growth of integrated education in the region in response to parental demand. The IEF seeks to bridge the financial gap between starting integrated schools and securing full government funding and support. It was established in 1998 with funding from EU Structural Funds, the Department of Education, the Nuffield Foundation, and the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. The IEF financially supports the establishment of new schools, the growth of existing schools, and those schools seeking to become integrated.[24]

In 2021–2022, there were 38 grant-maintained integrated schools (23 primary and 15 post-primary) and 30 controlled integrated schools (24 primary, five post-primary and one nursery); all post-primary schools in the sector are non-grammar. There were around 18,000 pupils in grant-maintained integrated schools and 8,000 pupils in controlled integrated schools, therefore around 26,000 pupils in 68 schools across the sector. The community backgrounds of pupils in grant-maintained integrated schools were 40% Catholic, 32% Protestant and 27% other, whereas the proportions for controlled integrated schools were 41% Protestant, 23% Catholic and 36% other.[4]

Irish-medium maintained

The Education (Northern Ireland) Order 1998 placed a duty on the Department of Education, similar to that already in existence in relation to integrated education through the 1989 Education Reform Order, "to encourage and facilitate the development of Irish-medium education". Pupils are usually taught most subjects through the medium of Irish, which is the second language of most of the pupils, whilst English is taught through English. This form of education has been described as Immersion education, and is now firmly established as a successful and effective form of bilingual education. It aims to develop a high standard of language competence in the immersion language (Irish) across the curriculum, but must also, and can, ensure a similar level of achievement in the first language (in this case, usually English) as that reached by pupils attending monolingual English medium schools.

Irish-medium schools, or Gaelscoileanna, are able to achieve grant-aided status, under the same procedures as other schools, by applying for maintained status. In addition to free-standing schools, Irish language medium education can be provided through units in existing schools; unit arrangements permit Irish-language-medium education to be supported where a free-standing school would not be viable. A unit may operate as a self-contained provision under the management of a host English-medium school and usually on the same site. In addition to this, there are two independent schools teaching through the medium of Irish. These are Gaelscoil Ghleann Darach in Crumlin and Gaelscoil na Daróige in Derry City.

Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta (CnaG) is the representative body for Irish-medium education, and was set up in 2000 by the Department of Education to promote, facilitate and encourage Irish-medium education. One of CnaG's central objectives is to seek to extend the availability of Irish-medium education to parents who wish to avail of it for their children, and it is supported in this role by Iontaobhas na Gaelscolaíochta (the trust fund for Irish-medium education.

In 2021–2022, there were 25 primary schools and two post-primary schools (both non-grammar) in the Irish-medium maintained sector, with around 5,000 pupils, and 10 Irish-medium units, educating around 1,500 pupils; pre-school education is also available in the Irish language.[4]

School buildings

Plans for investment in Northern Ireland schools and youth facilities were published in 2005, intended to address a reported problem of "historic under-investment". The "Investment Strategy for Northern Ireland 2005–2015" was published on 14 December 2005. To offer sufficient construction companies an opportunity to support this strategy, the Department of Education established the "Northern Ireland Schools Modernisation Programme ("NISMP"), with companies invited to express interest in works contracts in 2007.[25]

Further and higher education

Northern Ireland provides a wide range of options for further and higher education through its universities, regional colleges (for further education), and other specialist colleges for teacher training and the agri-food sector. The Open University and regional colleges, in particular, enroll large numbers of adult learners. Many young people choose to travel to Great Britain to continue their education although this has, for many years, caused concern about a 'brain drain' effect and the difficulty in retaining skills and knowledge in the region's economy. The relatively low cost of living and higher quality of life in smaller and closer-knit communities, though, is an attraction for many students and graduates from Britain, the rest of Ireland and elsewhere.

In 2019–2020, the last year before disruption to school exams by the Covid-19 pandemic, 48% of school leavers in Northern Ireland entered higher education, 29% entered further education, 10% entered training, 9% entered employment, 3% became unemployed and the destination for a further 2% was unknown.[26]

See also

- Education in the Republic of Ireland

- Controlled Schools' Support Council

- Council for Catholic Maintained Schools

- Lists of schools in Northern Ireland

- List of primary schools in Northern Ireland

- List of secondary schools in Northern Ireland

- List of grammar schools in Northern Ireland

- List of integrated schools in Northern Ireland

- List of further education colleges in Northern Ireland

- List of universities and colleges in Northern Ireland

- Segregation in Northern Ireland

References

- ↑ Estimate for the United Kingdom, from United Kingdom Archived 26 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, CIA World Factbook

- ↑ Archived 13 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Population estimates for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: mid-2019". ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Annual enrolments at schools and in funded pre-school education in Northern Ireland 2021–22" (PDF). education-ni.gov.uk. Department of Education. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ↑ "Further Education Sector Activity in Northern Ireland: 2016/17 to 2020/21" (PDF). economy-ni.gov.uk. Department for the Economy. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ↑ "Enrolments at UK Higher Education Institutions: Northern Ireland Analysis 2019/20" (PDF). economy-ni.gov.uk. Department for the Economy. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ↑ "Why CAFRE?". cafre.ac.uk. CAFRE. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ↑ "Printing of Ireland's first book, the 'Book of Common Prayer', to be commemorated – The Irish times". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 11 April 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ↑ Lenoach, Ciarán (31 October 2018). "New catalogue of books printed in Irish from 1571 to 1871 – RTE". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ↑ Tony Crowley (2002). The Politics of Language in Ireland 1366–1922: A Sourcebook. Routledge. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-134-72902-9.

- ↑ Tony Lyons, "The Hedge Schools of Ireland." History 24#6 (2016). pp 28-31 online Archived 15 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Antonia McManus (2002). The Irish Hedge School and Its Books, 1695–1831. Four Courts. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-85182-661-2. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ↑ Historians Adams and McManus are quoted in Michael C. Coleman, American Indians, the Irish, and Government Schooling: A Comparative Study (2005) p 35.

- ↑ Daire Keogh, "Forged in the Fire of Persecution: Edmund Rice (1762–1844) and the Counter-Reformationary Character of the Irish Christian Brothers." in Brendan Walsh, ed., Essays in the History of Irish Education (2016) pp. 83–103.

- 1 2 "THE DARING FIRST DECADE OF THE BOARD OF NATIONAL EDUCATION, 1831–1841, John Coolahan, University College Dublin, The Irish Journal of Education 1983 xvu 1 pp 35 54" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ↑ National Schools in the 19th Century – Kildare Place Society Archived 23 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine,

- ↑ CCEA. "Key Stage 3". Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ↑ CCEA. "The Statutory Curriculum at Key Stage 3" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ↑ Robbie Meredith (27 February 2019). "French, German or Spanish offered by fewer NI schools". BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ↑ "Mandarin Chinese". Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2021. South West College works in conjunction with some schools to offer after-school clubs for Mandarin Chinese.

- ↑ "Research and Information Service Briefing Paper 209/20: Academic Selection" (PDF). niassembly.gov.uk. Northern Ireland Assembly. 2020.

- ↑ "Education Act (Northern Ireland) 2014". legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ ""Churches and Christian Ethos in Integrated Schools", Macaulay, T 2009" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ↑ "The Report of the Independent Review of Integrated Education | Department of Education". Department of Education. 1 March 2017. Archived from the original on 20 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ↑ Her Majesty's Court of Appeal in Northern Ireland, Henry Brothers (Magherafelt) Limited, F B McKee and Company Ltd. and Desmond Scott and Philip Ewing trading as Woodvale Construction Company Ltd. and Department of Education for Northern Ireland, neutral citation No. [2011] NICA 59, paragraphs 6–7, judgment delivered 26 September 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2021

- ↑ "Qualifications and Destinations of Northern Ireland School Leavers: 2019–20" (PDF). education-ni.gov.uk. Department of Education. 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ↑ Only in Irish-medium schools

- ↑ Excluding English, and Irish in Irish-medium schools

- 1 2 Schools need only offer one language, but many schools offer students the chance to take two or three. French and German are common in most schools, while Irish is often found in Catholic schools. Spanish and Italian are sometimes offered too. CCEA offers GCSEs in French, German, Irish and Spanish, but GCSEs in Italian, Modern Greek, Polish and Portuguese are offered by other examination boards.

Further reading

- Dominic Murray, Alan Smith, Ursula Birthistle (1997), Education in Ireland, Irish Peace Institute Research Centre. ISBN 1-874653-42-9

External links

Government organisations

- Department of Education

- Department for the Economy (further education policy)

- Department for the Economy (higher education policy)

- Department for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (education and research)

- Education Authority

- Council for the Curriculum, Examinations & Assessment

- Education and Training Inspectorate

Resources

Support and advocacy organisations

- Controlled Schools' Support Council

- Transferor Representatives' Council

- Council for Catholic Maintained Schools

- Catholic Schools' Trustee Service

- Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta (for Irish-medium education)

- Iontaobhas na Gaelscolaíochta (Irish-medium education trust fund)

- Northern Ireland Council for Integrated Education

- Integrated Education Fund

- Governing Bodies Association (for voluntary grammar schools)

Universities and colleges