Union of Dutch National Solidarists Verbond van Dietsche Nationaal-Solidaristen | |

|---|---|

| |

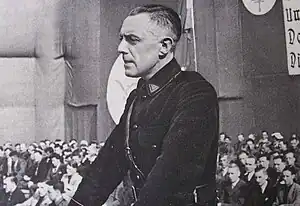

| Leader | Joris Van Severen |

| Founded | 6 October 1931 |

| Dissolved | 10 May 1941 |

| Merged into | Eenheidsbeweging-VNV |

| Headquarters | Izegem, West Flanders |

| Youth wing | Jong Dinaso |

| Paramilitary wing | Dinaso Militanten Orde |

| Ideology | National Solidarism[1] |

| Political position | Far-right |

| Colours | Orange White Blue |

| Slogan | "Dietschland en Orde" |

| Party flag | |

| |

Verdinaso (Verbond van Dietsche Nationaal-Solidaristen, lit. 'Union of Dutch National Solidarists'[8]), sometimes rendered as Dinaso,[9] was a small fascist political movement active in Belgium and, to a lesser extent, the Netherlands between 1931 and 1941.

Verdinaso was founded by Joris Van Severen, Jef François, Wies Moens, and Emiel Thiers on 6 October 1931 at a meeting in the Hôtel Richelieu in Ghent. It emerged from the Flemish Movement although, under Van Severen's leadership, it moved towards a novel authoritarian political ideology, which he referred to as National Solidarism. The organisation had initially called for the reunification of Flanders with the Netherlands in a Greater Netherlands (Dietschland) but discarded this ideal in 1934 in favour of a broader corporatist ideology calling for the establishment of a federated authoritarian polity on the model of the Burgundian Netherlands which would incorporate the whole of Belgium and possibly Luxembourg.[10] The party remained small but succeeded in attracting several young students and intellectuals inspired by Italian Fascism and Portugal's Estado Novo. It established a paramilitary wing in 1937, identified by its members' green shirts, known as the Dinaso Militant Order (Dinaso Militanten Orde).

Although Verdinaso never gained a mass following, its role in diminishing support for the established Flemish Front (Vlaamsche Front) at the 1929 elections led to the latter's decision to substantially reorganise itself in 1931 into the Flemish National League (Vlaamsch Nationaal Verbond) and to shift its ideological mainstream away from democratic reform and pacificism towards right-wing authoritarianism.[11]

Character and history

The party was against the parliamentary democracy and eventually advocated a corporative society ruled by the Belgian King. As such it never participated in elections and never became a potent political pressure group.

The Verdinaso initially advocated Flemish and Dutch nationalism. It proposed the union of Flanders with the Netherlands to form a Dietsland or Diets Rijk ("Dietsch Empire"), justifying this based on a shared history of the two lands under the Burgundians, and the emblematic rule of Charles I. In 1932, two of its leaders, François and Van Severen, were elected to the Chamber of Deputies; the same year, the party was joined by Victor Leemans, who wrote the work Het nationaal-socialisme, an apology for National Socialism.

After 1934, Verdinaso shifted its focus towards a Belgian identity circa 1939, becoming a bilingual (French-Dutch) movement, believing that the Belgian state should be founded on Roman Catholic corporatism – an economic model interpreted by Verdinaso from the Catholic social teaching, and akin to Integralism and the Action Française (an influence on Van Severen). Influential members, like Wies Moens, left the organization over what they viewed as treason to Dutch nationalism and a shift towards belgicism.[12] The party virulently opposed Communism on the left and liberal capitalism on the right; it was also somewhat antisemitic, occasionally venting the opinion that Jews, as well as Freemasons constituted a hidden power working against the interests of Dietsland. The movement also shifted from proposing a union between Flanders and the Netherlands to one between Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

In the elections of May 24, 1936, Verdinaso ran on a typical list with other Flemish nationalists under the common denominator Vlaams Nationaal Block, gaining 13% of the vote and 16 deputy seats; in 1939, it peaked at 15% of the vote and 17 seats. The Dinaso Militanten Orde had around 3,000 members, grouped under the leadership of François, and edited the newspapers Recht en Trouw and De Vlag (placed under the leadership of Moens).

When World War II, broke out Van Severen was killed in Abbeville, France, suspected of being an agent of Nazi Germany, and as part of some executions of Rexists and Belgian communists (both groups were suspected of pro-German activism, justified by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in the case of the latter). As a consequence, the Verdinaso lost a clear direction (despite Van Severen's replacement with François), and was eventually forced to join the Flemish National Union on May 5, 1941. Some of Verdinaso's members, who were advocating a strong Belgian authoritarian regime around King Leopold III, however, joined the resistance against the German occupation.[13]

Ideology

Verdinaso was based around the ideology of "National-Solidarism", which was a social doctrine that was firmly anti-Marxist and anti-capitalist. The party wished to reform society in an organic sense, that is to say, growing gradually, naturally, with respect for its nature, history and tradition. Verdinaso opposed both liberalism and parliamentary democracy.[14] With the Verdinaso, Van Severen wanted to form a leading elite that would conquer power in the state through its style and action, rather than overthrow it. The Verdinaso leaned toward the Conservative Revolution, more specifically with the Young Conservatives. There was also the influence of Charles Maurras's nationalist Action Française.

Notable members

References

Notes

- ↑ At its foundation, it supported Flemish separatism, but before long, the group, which was far-right, supported the Dietsch option.[3] Van Severen advocated the use of force to take over the existing Belgium and then to establish the Greater Belgium state that he supported.[4] He also advocated anti-parliamentarism, something that had been strengthened by his defeat in 1929, during which he felt moderates in the Frontpartij had deliberately sabotaged his re-election.[5] His vision would eventually expand to that of the Dietsche Rijk which, rather than splitting Flanders off from Belgium to form the new state, advocated the practical union of the Benelux countries into a single entity.[6]

Citations

- ↑ van Tienen, Paul (1958). Geschiedenis der conservatieve revolutie in Nederland (1st ed.). Scheveningen. ISBN 1-85973-274-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Rees, Biographical Dictionary of the Extreme Right, p. 402

- ↑ Carsten, The Rise of Fascism, p. 208-9

- ↑ Rees, Biographical Dictionary of the Extreme Right, p. 402

- ↑ Rees, Biographical Dictionary of the Extreme Right, p. 402

- ↑ Hans Rogger & Eugen Weber, The European Right: A Historical Profile, University of California Press, 1965, pp. 151-152

- ↑

Badie, Bertrand; Berg-Schlosser, Dirk; Morlino, Leonardo, eds. (7 September 2011). International Encyclopedia of Political Science. SAGE Publications (published 2011). ISBN 9781483305394. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

... fascist Italy ... developed a state structure known as the corporate state with the ruling party acting as a mediator between 'corporations' making up the body of the nation. Similar designs were quite popular elsewhere in the 1930s. The most prominent examples were Estado Novo in Portugal (1932–1968) and Brazil (1937–1945), the Austrian Standestaat (1933–1938), and authoritarian experiments in Estonia, Romania, and some other countries of East and East-Central Europe,

- ↑ Kossmann 1978, p. 626.

- ↑ Moore, Bob, ed. (2000). Resistance in Western Europe (1st ed.). Oxford: Berg. p. 267. ISBN 1-85973-274-7.

- ↑ Kossmann 1978, pp. 639–40.

- ↑ Kossmann 1978, p. 640.

- ↑ "Verbond van Dietsche Nationaal Solidaristen (Verdinaso) - NEVB Online". nevb.be. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ↑ De Bock, Walter. Extreem-rechts en de rijkswacht op 25 oktober 1936 : een poging tot staatsgreep in België ("The extreme right and the Gendarmerie on 25 October 1936 : an attempted coup in Belgium") (in Dutch). pp. 16–17. in : De Bock, Walter; et al. (1981). Extreem-rechts en de staat ("The extreme right and the state") (in Dutch). Antwerpen: Uitgeverij EPO. pp. 11–58. ISBN 90-6445-971-1.

- ↑ "Blokwatch - Nationale webstek over het Vlaams Belang - Het programma van het Verdinaso". 10 November 2007. Archived from the original on 10 November 2007.

Further reading

- Kossmann, E. H. (1978). The Low Countries, 1780-1940. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-822108-8.

External links

Media related to Verdinaso at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Verdinaso at Wikimedia Commons- L'Extrême droite en Flandre hier

- Rues sans complexes Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine - Belgian fascists that some streets were still named after in 1999 (short biographies).