Rosendale cement is a natural hydraulic cement that was produced in and around Rosendale, New York, beginning in 1825.[1] From 1818 to 1970 natural cements were produced in over 70 locations in the United States and Canada. More than half of the 35 million tons of natural cement produced in the United States originated with cement rock mined in Ulster County, New York, in and around the Town of Rosendale in the Hudson River Valley.[2] The Rosendale region of southeastern New York State is widely recognized as the source of the highest quality natural cement in North America.[3] The Rosendale region was also coveted by geologists, such as W. W. Mather, a geologist working for the State of New York, for its unusual exposed bedrock.[1] Because of its reputation, Rosendale cement was used as both a trade name and as a generic term referring to any natural hydraulic cement in the US. It was used in the construction of many of the United States' most important landmarks, including the Brooklyn Bridge, the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty, Federal Hall National Memorial, and the west wing of the United States Capitol building.[4]

Composition

Rosendale natural cement from the Rosendale area was produced from fine-grained, high silica and alumina dolomite mined from the Rosendale and Whiteport Members of the late Silurian Rondout Formation. Although composition varied, one text quotes CaCO3 45.91%, MgCO3 25.14%, silica and insoluble 15.37%, Al2O3 and Fe2O3 11.38%, water and undetermined 1.20%.[5]

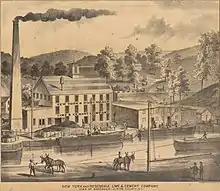

Production

Mining

Room and pillar mining was utilized in the majority of Rosendale area mines, though there are examples of open quarries. A combination of blasting and hand tools, such as sledge hammers, were used at the height of production to extract the dolomite, which was transported to the surface via steam hoists, and then to nearby kilns by narrow gauge rail for calcination.[6]

Calcination and grinding

Natural cement is produced in a process that begins with the calcination of crushed dolomite in large brick kilns, fired initially by wood and then by coal transported to Rosendale by the D&H canal. The resulting clinker is ground into progressively smaller particles. The final product is a fine powder of 50 mesh size. Unlike Portland cement, Rosendale cement does not require mixing of chemical additives. Historically, this natural cement product was packaged in paper-lined wooden barrels weighing 300 lbs, or in heavy canvas bags.[7]

History

Early history

Natural cement rock was first discovered by Canvass White in 1818 in Chittenango, east of Syracuse, who developed a process for the manufacture of cement which he patented in 1820.[1] In Rosendale, cement rock was discovered in the summer of 1825 by Canvass White or an assistant engineer for the Delaware and Hudson Canal James McEntee.[8] The cement was competitive in quality to that of Chittenango and because of its proximity to D&H canal construction, a contract to supply the cement was awarded to John Littlejohn, who commenced production in High Falls, New York in 1826.[9] Littlejohn completed his contract, and Judge Lucas Elemdorf picked up cement manufacturing in Lawrenceville, a hamlet of Rosendale, grinding the cement on the property of Jacob Low Snyder around 1827.[10] Soon, several cement works were founded most notably by Watson E. Lawrence, of whom Lawrenceville is named, the aforementioned Canvass White, and his brother Hugh White, who founded Whiteport, a hamlet in Rosendale. Another notable cement plant was located in Binnewater, a hamlet of Rosendale, run by F. O. Norton, in about 1868, and another by A. J. Snyder on his own lands in Lawrenceville in 1850.[11]

According to Dietrich Werner, the former president of the Century House Historical Society, the proximity of the Rosendale region to the Delaware and Hudson Canal enabled the production and shipment of the natural cement. Soon, Rosendale cement could be found in all major American east coast ports and in the West Indies.[1]

Industrial Revolution

With the onset of the American Industrial revolution, the demand for cement increased. Roads, dams, power plants, bridges, and various North American government projects such as the construction of cisterns, wet cellars and the Croton Aqueduct system were rapidly being built throughout the American landscape.[1] All of these structures utilized Rosendale natural cement.[12] In addition to large structures, natural cement was also used to create mortars, stuccos, lime-washes, grouts, and concretes.[2] In the final year of the 19th century, Rosendale’s cement industry peaked, producing nearly 8.5 million barrels a year. Remnants of cement operations including kilns and the Widow Jane Mine are preserved in the Snyder Estate Natural Cement Historic District.[13]

Portland cement and the decline of Rosendale

By the 20th century, the demand for Rosendale natural cement dropped precipitously, while Portland cement rapidly became the most popular building material. There are many reasons for the decline, but it is mainly attributed to advances in the production of Portland cement, especially the horizontal rotary cylinder kiln, which decreased the cost significantly, while tripling output over previous kilns. At the same time, the American Society of Testing Engineers changed their standards to favor Portland cement, which was generally perceived as more consistent and with a much shorter drying time.[7] By 1910, production dropped from a high of 8.5 million barrels a year to 1 million barrels a year, and by 1920 there was only one factory still in operation, that of A.J. Snyder.[14] One revival of the industry occurred in the mid 20th century, when A.J. Snyder began to experiment by combining natural cement with Portland cement after New York State engineers noticed the durability of Rosendale cement.[8] Notable structures built out of this hybrid are New York’s Rockefeller Center in the late 1930s, the New York State Thruway in the 1950s, and the St. Lawrence Seaway in the late 1950s and early 1960s.[2] Various writers, including Uriah Cummings, appear to support the anecdotal evidence that Rosendale cement was highly durable, and with tensile strength equal to or greater than Portland, however the decline in the industry was unstoppable.

By 1970, A. J. Snyder's last Rosendale, NY mine closed. Six years later, natural cement ceased to be produced altogether in the US.[15] Natural cement was not available in the United States for over thirty years.[16]

Revival and present day production

While the natural cement industry declined in the early 20th century, demand was later revived by efforts to restore historic buildings and structures using historically accurate materials.[17] This led to the re-opening in 2004 of the historic Hickory Bush Quarry in Rosendale, New York, operated by Freedom Cement, which currently sells authentic Rosendale cement under the Century Brand trademark.[18] This product has been used in the restoration of Fort Jefferson National Monument in Florida and the High Bridge in New York City, both of which were originally built using natural cement. Another company, Edison Coatings, continues the tradition of liberal use of the name "Rosendale cement" to market its natural hydraulic cement, though the materials for this product are extracted elsewhere.[19] Unlike the exhausted or inaccessible sources elsewhere, the mines in Rosendale, New York, still hold countless accessible tons of the highest quality natural cement rock, capable of supplying long-term future needs.[2]

In 2006, industry standards for the performance properties of natural cement were reintroduced by ASTM International under ASTM C10, Standard Specification for Natural Cement.[20] Over the past ten years, The Society for the Preservation of Historic Cements, Inc has hosted three conferences on American Natural Cement that attract experts across disciplines, including geologists, engineers, preservationists, historians and architects.[21]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Werner, Dietrich; Burmeister, Kurtis (2007). "An Overview of the History and Economic Geology of the Natural Cement Industry at Rosendale, Ulster County, New York". Journal of ASTM International. 4 (6): 100672. doi:10.1520/JAI100672. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Edison, Michael P. (2007). "Formulating with Rosendale Natural Cement" (PDF). Journal of ASTM International. 4: 100625. doi:10.1520/JAI100625.

- ↑ Werner, Dietrich; Burmeister, Kurtis (2007). "An Overview of the History and Economic Geology of the Natural Cement Industry at Rosendale, Ulster County, New York". Journal of ASTM International. 4 (6): 100672. doi:10.1520/JAI100672 – via ASTM Compass.

- ↑ Cummings, Uriah (1898). American Cements, Rogers & Manson, p. 297,298, ISBN 1334181586.

- ↑ Wanless, Harold rollin (1921). "Final Report on the History of the Rosendale Cement District"

- ↑ Werner, Dietrich; Burmeister, Kurtis (2007). "An Overview of the History and Economic Geology of the Natural Cement Industry at Rosendale, Ulster County, New York". Journal of ASTM International. 4 (6): 9, 10. doi:10.1520/JAI100672 – via ASTM Compass.

- 1 2 Howe, Dennis E. (2009). Industrial Archeology of a Rosendale Cement Works at Whiteport, Whiteport Press, p. 25,26.

- 1 2 Gilchrist, Ann. (1976). Footsteps Across Cement, A History of the Township of Rosendale, New York,Self Publish, p. 60.

- ↑ Sylvester, Nathaniel Bartlett (1880). History of Ulster County New York, Everts & Peck, p. 240.

- ↑ Gilchrist, Ann. (1976). Footsteps Across Cement, A History of the Township of Rosendale, New York,Self Publish, p. 44.

- ↑ Gilchrist, Ann. (1976). Footsteps Across Cement, A History of the Township of Rosendale, New York,Self Publish, p. 47.

- ↑ Edison, Leyla. "Perspectives: The Reintroduction of Natural Cement". Journal of ASTM International. 4: xi.

- ↑ "The Century House Historical Society".

- ↑ Gilchrist, Ann. (1976). Footsteps Across Cement, A History of the Township of Rosendale, New York,Self Publish, p. 59.

- ↑ "History of Rosendale Cement". www.rosendalecement.net. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ↑ "NaturalCement.org". www.naturalcement.org. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ↑ Edison, Michael P., "The American Natural Cement Revival", January 2006, ASTM Standardization News.

- ↑ "Century Brand® Natural Cement", Freedom Cement, LLC.

- ↑ "Rosendale Natural Cement Products", Edison Coatings, Inc.

- ↑ "ASTM C10, Standard Specification for Natural Cement", ASTM International.

- ↑ "The Birth Of The American Cement Industry" (PDF). www.naturalcement.org. Retrieved 8 December 2018.