Energy in Armenia is mostly from natural gas.[1] Armenia has no proven reserves of oil or natural gas and currently imports most of its gas from Russia. The Iran-Armenia Natural Gas Pipeline has the capacity to equal imports from Russia.[2]

Despite a lack of fossil fuel, there are significant domestic resources to generate electricity in Armenia. The Armenian electrical energy sector has had a surplus capacity ever since emerging from a severe post-Soviet crisis in the mid-1990s, thanks to the reopening of the Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant, which was built in 1979 and supplies over 40% of the country's electricity.[3] Armenia has plans to build a new nuclear power plant in order to replace the aging and dangerous[4] Metsamor, possibly a small modular reactor.[5] The country also has eleven hydroelectric power plants and has plans to build a geothermal power plant in Syunik. Most of the rest of Armenia's electricity is generated by the natural gas-fired thermal power plants in Yerevan (completed in 2010) and Hrazdan.

Upon gaining independence, Armenia signed the European Energy Charter in December 1991, the charter is now known as the Energy Charter Treaty which promotes integration of global energy markets.[6] Armenia is also a partner country of the EU INOGATE energy programme, which has four key topics: enhancing energy security, convergence of member state energy markets on the basis of EU internal energy market principles, supporting sustainable energy development, and attracting investment for energy projects of common and regional interest.[7] Since 2011, Armenia holds observer member status in the EU's Energy Community.

History and geopolitics

Before the USSR collapsed, oil imports made up about half of Armenia's primary energy supply of 8000 ktoe (compare to 3100 ktoe in 2016).[8][9]

Back then, oil made its way to Armenia via a direct rail link from Armenia-Georgia-Russia, but since the Abkhazia-Georgia border is closed fuel is transported across the Black Sea to Georgia from where it makes its way to Armenia via rail cars. Further restriction to Armenian oil imports represents economic blockade maintained by Azerbaijan to the East, and Turkey to the West. The blockade began shortly after the outbreak of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War and was upheld ever since, despite a cease fire agreement in 1994.[10]

Rankings

Armenia was ranked 43rd among 125 countries at Energy Trilemma Index in 2018.[11] The index ranks countries on their ability to provide sustainable energy through 3 dimensions: Energy security, Energy equity (accessibility and affordability), Environmental sustainability.

Primary energy supply

Total primary energy supply in Armenia in 2016 amounted to 3025 ktoe (1000 tonnes of oil equivalent).[9] This roughly matches or surpasses production of previous years.[8] TPES included Production (963 ktoe), Imports (2235 ktoe), Exports (-122 ktoe), International Marine Bunkers (0 ktoe), International Aviation Bunkers (-45 ktoe), Stock Changes (-5 ktoe). Armenia's Total Final Consumption is 2120 (ktoe), Losses -180 (ktoe), Industry 320 (ktoe), Transport 622 (ktoe) and Residential 786 (ktoe).

Natural reserves

Armenia has no proven oil or gas reserves. Earlier explorations failed to deliver satisfactory results in the past .

In 2018 new permits for oil and gas exploration were issued to Tashir Group affiliated companies.[12][13][14]

Oil

According to Statistical Committee of Armenia no oil was imported in 2016, but rather its refinement products.[9]

Proposed Iranian pipeline

Armenian and Iranian authorities have for years been discussing an oil pipeline (distinct from the existing Iran-Armenia natural gas pipeline) that will pump Iranian oil products to Armenia. As of early 2011, no concrete dates have been set for the construction.[15] Armenian Energy Minister Armen Movsisian has said that the construction will take two years and cost Armenia about $100 million.[15] Earlier Iran's oil minister said that the 365-kilometer pipeline could go on stream by 2014.[15] Iran plans to export 1.5 million liters of gasoline and diesel fuel a day to Armenia through the pipeline; Armenia's annual demand for refined oil products stands at around 400,000 metric tons.[15]

Natural gas

Natural gas represents a large portion of total energy consumption in Armenia, accounting for 50% and is the primary means of winter heating in the country.

Gazprom Armenia (owned by the Russian gas giant Gazprom) owns the natural gas pipeline network within Armenia and holds a monopoly over the import and distribution of natural gas to consumers and businesses.

Armenia's thermal power stations (which supply approximately 24% of its electricity) run on natural gas, making Armenia (at the present time) dependent on imported Russian gas.[16]

Russian-Georgian pipeline

The Russian gas export monopoly Gazprom supplies Armenia with gas through a pipeline that runs through Georgia.[17] In 2007, Gazprom provided Armenia with just under 2 billion cubic meters of natural gas. As a transit fee, Armenia pays Georgia approximately 10% of the gas that was destined to reach Armenia.[18] Russian natural gas supplies to Georgia and Armenia are provided by two main pipelines: the North Caucasus-Transcaucasus pipeline (1,200 mm diameter) and the Mozdok-Tbilisi pipeline (700 mm diameter).[19]

In 2008, Armenia imported 2.2 billion cubic meters of natural gas from Russia.[20]

Iranian pipeline

A new gas pipeline, the Iran-Armenia Natural Gas Pipeline, was completed in October, 2008. It is owned and operated by Gazprom Armenia and links Armenia to neighboring Iran, which has the world's second largest natural gas reserve after Russia.[21] It has a capacity to pump 2.3-2.5 billion cubic meters of Iranian gas per year. The Armenian Ministry of Energy said in 2008 that it "does not yet have a need" for Iranian gas.[22] Analysts said that Armenia's reluctance to import Iranian gas was a result of pressure from Russia which maintains a monopoly over Armenia's natural gas market.[22]

Gazprom wholly owns a crucial 24-mile section of the pipeline which Armenia surrendered in exchange for natural gas supplies from Russia at prices well below the European average until 2009. According to an analyst, Armenia "effectively bargained away its future prospects for energy sources in return for cheaper prices now." While Armenia could diversify its gas supply, with control of the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline, Gazprom now controls the competitors' supply.[21]

In 2009 Armenia was importing 1-1.5 million cubic meters of Iranian natural gas, paying for this by electricity exports.[20]

Armenia receives about 370 million cubic meters of gas a year from Iran, which is converted into electricity and is sent back to Iran.[23]

Gas from Turkmenistan might be supplied via Iran.[24]

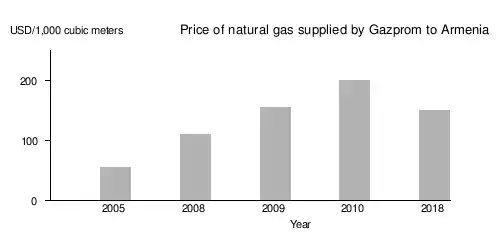

Pricing

According to the agreements reached in 2017 by Karapetyan government gas import price stands at $150 for one thousand cubic meters throughout year 2018.[25] Gazprom Armenia sells it to Armenian households at almost $300.[26]

Electricity

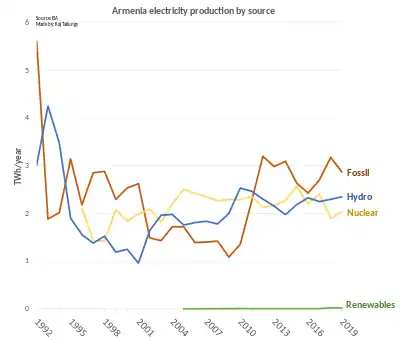

Since 1996 three main energy sources for electricity generation in Armenia were natural gas, nuclear power and hydropower.[27]

Despite a lack of fossil fuel, Armenia has significant domestic electricity generation resources. In 2006, non-thermal domestic electricity generation accounted for 76% of total generation: 43% nuclear and 33% hydroelectric. In comparison, in 2002, these numbers were 56%, 32%, and 26%.

In 2006, Armenia's power plants generated a total of 5,940.9 million KWh of electricity of which 5,566.7 million KWh were delivered (374.2 million KWh – or 6.3% – was consumed by the producing plants).[28] Thus, in 2006, Armenia's power plants on average generated 678.2 MW of power, while the country's electricity consumption rate on average was 635.5 MW.

Armenia has a total of 11 power stations and 17 220 kV substations. A map of Armenia's National Electricity Transmission Grid can be found at the website of the Global Energy Network Institute here .

Nuclear power

.jpg.webp)

Nuclear power provides 38% of the electricity in Armenia through one operating nuclear reactor, Unit 2 of Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant, which is a WWER-440 reactor with extra seismic reinforcement.[29] It was created in 1976 and is the only nuclear power plant in the South Caucasus. However, after the Spitak earthquake in 1988, the nuclear power plant's operation was forced to stop,[30] becoming one of the causes of the Armenian energy crisis of 1990's. The second unit of the NPP was restarted in October 1995, putting an end to the 'dark and cold years'.

While Armenia is the sole owner of the plant, the Russian company United Energy Systems (UES) manages the Metsamor NPP. Nuclear fuel must be flown in from Russia.

A modernization of NPP is scheduled for 2018, which will enhance the safety and increase installed capacity by 40-50 MW.[31]

Armenia also explores the possibilities of small modular reactor that would give flexibility and the opportunity to build a new nuclear power plant in a short time.[31]

Earlier it was reported that Armenia is looking for a new reactor with 1060 MW capacity in 2026.[32]

Armenia operates one Soviet-designed VVER-440 nuclear unit at Metsamor, which supplies over 40% of the country's energy needs. The EU and Turkey have expressed concern about the continuing operation of the plant. The Armenian energy minister has announced that a US$2 billion feasibility study of a new 1,000 MWe nuclear power plant is to be carried out in cooperation with Russia, the United States and the IAEA. Russia has agreed to build the plant in return for minority ownership of it. Furthermore, the USA has signalled its commitment to help Armenia with preliminary studies.

Armenia's Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant has an installed capacity of 815 MW, though only one unit of 407.5 MW is currently in operation.[33]

Because Turkey, despite its WTO obligation, blockades Armenian borders, nuclear fuel is flown in from Russia.[34]Used fuel is sent back to Russia.

Armenia signed a cooperation agreement with the European Organization for Nuclear Research in March 1994.[35] Since 2018, Armenia has also signed a cooperation agreement with the European Atomic Energy Community.[36]

Metsamor nuclear power plant provides more than 40 percent of power in Armenia; however, it is aging and will need to be replaced soon. It has received much financing for modernizing its systems and safety features.[37] Russia has extended a loan of $270 million and a $30 million grant for extending the lifetime of Metsamor NPP in 2015, which will be coming to an end in 2016. The funds are to be provided for 15 years with a 5-year grace period and an interest rate of annually 3%.[38]

Plans for building a new nuclear power plant have been discussed. In July 2014, the energy minister of Russian Federation announced that Russia is willing to provide US$4.5 billion out of US$5 billion needed for construction of a new nuclear power plant.[39] In 2014, the construction of a new power plant was approved by the Armenian government, which was to be started in 2018.

Fossil gas power

During 2010–2017 thermal power plants (running on imported natural gas from Russia and Iran) provided about one-third of Armenia's electricity.[40]

Thermal power plants (running on natural gas) in Armenia have an established capacity of 1,756 MW.[33]

The following table lists thermal power plants which together account for 24% of Armenia's domestic electricity generation.[41]

| Plant | Year built | Operational capacity (MW) | 2019 Electricity Generation[42] (GWh) | Ownership |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hrazdan Thermal Power Plant | 1966–1974; 2012 | units 1-4: 1,110;

unit 5: 480 |

467 (units 1-4);

378 (unit 5) |

units 1-4: Hrazdan Power Company, owned by the family of Samvel Karapetyan;

unit 5: Gazprom Armenia |

| Yerevan Thermal Power Plant | 1963–1967[43] | 550 | 1087 |

In April 2010, a new natural gas-fired thermal power plant was inaugurated in Yerevan, making it the first major energy facility built in the country since independence.[40] The plant will reportedly allow Armenia to considerably cut back on use of natural gas for electricity production, because officials say it will also be twice as efficient as the plant's decommissioned unit and four other Soviet-era facilities of its kind functioning in the central Armenian town of Hrazdan.[40] With a capacity of 242 megawatts, its gas-powered turbine will be able to generate approximately one-quarter of Armenia's current (as of 2010) electricity output.[40] The state-of-the-art plant was built in Yerevan in place of an obsolete facility with a $247 million loan provided by the Japanese government through the Japan Bank of International Cooperation (JBIC). The long-term loan was disbursed to the Armenian government on concessional terms in 2007.[40]

Armenia's energy sector will expand further after the ongoing construction of the Hrazdan thermal plant's new and even more powerful Fifth Unit.[40] Russia's Gazprom monopoly acquired the incomplete facility in 2006 as part of a complex agreement with the Armenian government that raised its controlling stake in the Armenian gas distribution network to a commanding 80 percent. The Russian giant pledged to spend more than $200 million on finishing its protracted construction by 2011.[40]

The new Yerevan and Hrazdan TPP facilities will pave the way for large-scale Armenian imports of natural gas from neighboring Iran through a pipeline constructed in late 2008. Armenia began receiving modest amounts of Iranian gas in May 2009. With Russian gas essentially meeting its domestic needs, it is expected that the bulk of that gas will be converted into electricity and exported to the Islamic Republic.[44]

In late December 2010, the Armenian Energy Ministry announced that the fifth block of the Hrazdan thermal power plant will go online by April 2011.[44] Although construction on the fifth block began in the late 1980s, the Armenian government tried to unsuccessfully finish it in the late 1990s. The current project is part of a 2006 deal between Gazprom and the Armenian government, in which Gazprom acquired the incomplete facility and increased its stake in Armenia's gas distribution network, in turn pledging to spend $200 million in completing the project by 2011.[44]Hydro

Hydro power plants provide 70 percent of Armenia's renewable energy. Major HPP capacities are installed within Sevan-Hrazdan Cascade and Vorotan Cascade.[47] The hydropower potential of Armenia is reported to be 21.8 billion kWh.

As of the 1 January 2018, electricity was generated by 184 small HPPs, with total installed capacity of 353 MW. In 2017 the generation of the electricity from small HPPs was around 862 million kW*h, which is about 11% of the total generated electricity in Armenia (7762 million kW*h). As of 1 January 2018, and according to the provided licenses, 36 additional SHPPs are under construction, with about total projected 69 MW capacity and 250 million kW*h electricity annual supply.[48][49]

The economically justified hydropower potential of Armenia is around 3.600 GWh/year.From this amount, 1.500 GWh/year (or about 42% of economically justified hydropower potential) has been developed already.[50]Six of the plants are in the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh.[51]Solar

Solar energy is widely available in Armenia due to its geographical position and is considered a developing industry. In 2022 less than 2% of Armenia’s electricity was generated by solar power.[52]

The use of solar energy in Armenia is gradually increasing.[53] In 2019, the European Union announced plans to assist Armenia towards developing its solar power capacity. The initiative has supported the construction of a power plant with 4,000 solar panels located in Gladzor.[54]

Solar power potential in Armenia is 8 GW according to the Eurasian Development Bank.[55] The reason for this is that average solar radiation in Armenia is almost 1700 kWh/m2 annually.[56] One of the well-known utilization examples is the American University of Armenia (AUA) which uses it not only for electricity generation, but also for water heating. The Government of Armenia is promoting utilization of solar energy.[57][58]

In 2018 the amount of solar power produced in Armenia increased by nearly 50 per cent. Government figures show that Armenia's solar power average is 60 per cent better than the European average.

In March 2018 an international consortium consisting of the Dutch and Spanish companies won the tender for the construction of a 55 MW solar power plant Masrik-1. The solar power station is planned to be built in the community of Mets Masrik of the Gegharkunik region entirely at the expense of foreign investments. The expected volume of investments in this generation facility will be about $50 million. Construction of the plant was expected to be completed by 2020.[59] In May 2019 the deadline for start of financing the Masrik-1 solar power plant construction project has been extended by 198 days.[60]Renewable energy

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Armenia energy profile – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 2023-01-12.

- ↑ "Iran and Armenia agree to double gas trade | Eurasianet". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 2023-01-12.

- ↑ "New Armenian Power Plant Set For Launch", Armenia Liberty (RFE/RL), December 21, 2010.

- ↑ D'Agostino, Susan (2021-03-05). "Armenia's nuclear power plant is dangerous. Time to close it". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved 2023-09-16.

- ↑ amartikian (2023-06-05). "Construction of a new nuclear power plant: who will be Armenia's energy partner?". English Jamnews. Retrieved 2023-09-16.

- ↑ "Energy Charter Treaty Members".

- ↑ INOGATE website

- 1 2 "Total primary energy supply in Armenia (1990–2015)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-12-03. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- 1 2 3 "Energy balance of the Republic of Armenia, 2016" (PDF).

- ↑ Official Energy Statistics from the U.S. Government – Caucasus Region, Energy Information Administration of the U.S. Department of Energy

- ↑ "WEC Energy Trilemma Index Tool". trilemma.worldenergy.org. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

- ↑ "Positive Opinion to 'Tashir Capital': Company Will Search for Oil and Gas in Shirak, Lori, and Tavush". www.ecolur.org. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- ↑ "'Tashir Capital' Intends to Search for Oil and Gas in Yerevan". www.ecolur.org. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- ↑ "Billionaire Samvel Karapetyan Exploring for Oil and Gas Around Yerevan – Hetq – News, Articles, Investigations". Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- 1 2 3 4 "No Firm Date Set For Work On Another Armenian-Iranian Pipeline", Armenia Liberty (RFE/RL), February 15, 2011.

- ↑ "Armenian Power Utility Rules Out Price Rise", Armenian Liberty (RFE/RL), July 28, 2008.

- ↑ "Armenia: Gas Price Hike Poses Challenge for Government", EurasiaNet, April 24, 2008.

- ↑ "Georgia/Russia: Both Sides Move Closer On Gas Issues" Archived 2007-06-24 at archive.today, Armenian Liberty (RFE/RL), December 21, 2005.

- ↑ Russian Gas Supplies to Georgia, Armenia Cut Over Pipeline Blasts – Ministry, RIA Novosti, January 22, 2006.

- 1 2 Armenia to import gas from Iran Archived 2013-04-19 at archive.today, Interfax-Ukraine (December 22, 2009)

- 1 2 Resolving a Supply Dispute, Armenia to Buy Russian Gas, The New York Times, April 7, 2006.

- 1 2 Armenia: New Projects A Stab At Independence From Moscow? Archived 2012-10-05 at the Wayback Machine, EurasiaNet.org, October 17, 2008.

- ↑ "Armenian government is looking into chances to have gas price reduced". arka.am. 10 October 2018. Retrieved 2018-10-18.

- ↑ "Iran Willing to Swap Gas from Turkmenistan to Armenia – Asbarez.com". Retrieved 2023-01-12.

- ↑ "New Armenia energy minister comments on gas price". news.am. Retrieved 2018-10-18.

- ↑ "Pashinyan creates task force to look into natural gas price". arka.am. 24 September 2018. Retrieved 2018-10-18.

- ↑ "Electricity generation by fuel in Armenia (1990–2015)" (PDF).

- ↑ 2006Q4 Electric Power: Main Indicators Archived 2011-05-31 at the Wayback Machine, Public Services Regulatory Commission of The Republic of Armenia, 2007.

- ↑ "Nuclear Power Plant Construction". JamesTown. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ↑ "An Energy Overview of Armenia". Global Energy Network Institute. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- 1 2 "Modernization to increase the capacity of Armenian nuclear power plant by 10%". arka.am. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- ↑ "Nuclear Power in Armenia - World Nuclear Association". www.world-nuclear.org. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- 1 2 "Electric Power in Asia and the Pacific 2001–2002: Armenia" Archived 2008-10-08 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations ESCAP.

- ↑ Official Energy Statistics from the U.S. Government – Caucasus Region, Energy Information Administration of the U.S. Department of Energy

- ↑ Our Member States, 2020-01-07.

- ↑ Armenian president declares readiness to enhance cooperation with European Union, 2019-10-22.

- ↑ "Armenia's Metsamor nuclear power station – most dangerous in the world?". ZME Science. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ "PSRC to consider Metsamor nuclear power plant's 2016 investment program". Arka News Agency. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ "Nuclear Power in Armenia". World Nuclear Association. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Armenia Inaugurates New Power Plant", Armenia Liberty (RFE/RL), April 20, 2010.

- ↑ Map of Armenian Electricity Grid, Global Energy Network Institute, September, 2000.

- ↑ "ENA Annual Report 2019" (PDF).

- ↑ "General Information on Armenian Power Sector" Archived 2009-02-28 at the Wayback Machine, Renewable Energy Armenia (Danish Energy Management A/S).

- 1 2 3 "New Armenian Power Plant Set For Launch", Armenia Liberty (RFE/RL), December 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Energy Profile – Armenia" (PDF). Irena. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-12-29. Retrieved 2023-05-27.

- ↑ "Technical Report – Quantifying Fiscal Risks from climate change". IMF. Archived from the original on 2023-05-27. Retrieved 2023-05-27.

- ↑ "Hydro Energy". Ministry of Energy Infrastructures and Natural Resources of the Republic of Armenia. Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ↑ "Hydro Energy - Investment projects - Projects - www.minenergy.am". www.minenergy.am. Archived from the original on 2018-04-12. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ↑ "Small Hydro Power Plants in Armenia". Armenian Community Council of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 2 May 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ↑ "Hydropower Potential of Armenia" Archived 2009-02-28 at the Wayback Machine, Renewable Energy Armenia (Danish Energy Management A/S).

- ↑ "Six months into blockade, Nagorno-Karabakh faces energy crisis as key reservoir dries up". Archived from the original on 2023-05-27. Retrieved 2023-05-27.

- ↑ "Armenia - Energy". www.trade.gov. Retrieved 2023-05-27.

- ↑ "Արևային-կայանների-կիրառումը" (PDF). gea.am (in Armenian). Green Energy Association. August 2016. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ↑ "EU boosts eco-tourism and renewable energy in Armenia with new solar power plant - EU Neighbours east".

- ↑ "Eurasian Development Bank to finance 11 solar power plants in Armenia". ceenergynews.com. 2022-08-19. Retrieved 2023-05-27.

- ↑ "Solar Energy". Ministry of Energy of Armenia. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ↑ "Legislative Reform to Promote Solar Energy in Armenia". Renewable Energy World. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ↑ "Solar Heating and Cooling in Armenia". Inforse-Europe. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ↑ "Solar power plant Masrik-1 to build a consortium of Dutch and Spanish companies". finport.am. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- ↑ "Deadline for start of financing the Masrik-1 solar power plant construction project has been extended by 198 days". www.finport.am. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- ↑ Eduard Karapoghosyan (14 June 2011). "Armenian Energy Sector Overview" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-08-23.

External links

- Armenian Nuclear power plant

- Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources of Armenia

- Public Services Regulatory Commission of The Republic of Armenia Archived 2019-10-12 at the Wayback Machine (statistics on electricity generation & consumption, natural gas consumption, and thermal energy generation)

- Hrazdan Energy Company Archived 2008-06-15 at the Wayback Machine