Frontispiece to volume 1 by Josiah Wood Whymper, entitled "Adventure with Curl-Crested Toucans". The image is misleading as Bates was not carrying a gun when he encountered the birds.[1] | |

| Author | Henry Walter Bates |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | E. W. Robinson, Josiah Wood Whymper, Joseph Wolf, Johann Baptist Zwecker, etc. |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Natural history, Travel |

| Publisher | John Murray |

Publication date | 1863 |

| Pages | 466 |

The Naturalist on the River Amazons, subtitled A Record of the Adventures, Habits of Animals, Sketches of Brazilian and Indian Life, and Aspects of Nature under the Equator, during Eleven Years of Travel, is an 1863 book by the British naturalist Henry Walter Bates about his expedition to the Amazon basin. Bates and his friend Alfred Russel Wallace set out to obtain new species and new evidence for evolution by natural selection, as well as exotic specimens to sell. He explored thousands of miles of the Amazon and its tributaries, and collected over 14,000 species, of which 8,000 were new to science. His observations of the coloration of butterflies led him to discover Batesian mimicry.

The book contains an evenly distributed mixture of natural history, travel, and observation of human societies, including the towns with their Catholic processions. Only the most remarkable discoveries of animals and plants are described, and theories such as evolution and mimicry are barely mentioned. Bates remarks that finding a new species is only the start; he also describes animal behaviour, sometimes in detail, as for the army ants. He constantly relates the wildlife to the people, explaining how the people hunt, what they eat and what they use as medicines. The book is illustrated with drawings by leading artists including E. W. Robinson, Josiah Wood Whymper, Joseph Wolf and Johann Baptist Zwecker.

On Bates's return to England, he was encouraged by Charles Darwin to write up his eleven-year stay in the Amazon as a book. The result was widely admired, not least by Darwin:

The best book of Natural History Travels ever published in England.

— Charles Darwin, Letter to Bates (1863)[2]

Other reviewers sometimes disagreed with the book's support for evolution, but generally enjoyed his account of the journey, scenery, people, and natural history. The book has been reprinted many times, mostly in Bates's own effective abridgement for the second edition, which omitted the more technical descriptions.

Publication history

The first edition, in 1863, was long and full of technical description. The second edition, in 1864, was abridged, with most of the technical description removed, making for a shorter and more readable book which has been reprinted many times. Bates prefaced the 1864 edition by writing

Having been urged to prepare a new edition of this work for a wider circle than that contemplated in the former one, I have thought it advisable to condense those portions which, treating of abstruse scientific questions, presuppose a larger amount of Natural History knowledge than an author has a right to expect of the general reader.

— Henry Bates[P 1]

An unabridged edition was reissued only after 30 years, in 1892; it appeared together with a 'memoir' of Bates by Edward Clodd.

Major versions

- Bates H.W. 1863. The naturalist on the river Amazons. 2 volumes, Murray, London.

- Bates H.W. 1864. The naturalist on the river Amazons. 2nd edition as one volume, Murray, London. [abridged by removing natural history descriptions; much reprinted]

- Bates H.W. 1892. The naturalist on the river Amazons, with a memoir of the author by Edward Clodd. [only full edition since 1863, with good short biography by Clodd]

Approach

In 1847, Bates and his friend Alfred Russel Wallace, both in their early twenties,[lower-alpha 1] agreed that they would jointly make a collecting trip to the Amazon "towards solving the problem of origin of species".[1] They had been inspired by reading the American entomologist William Henry Edwards's pioneering 1847 book A Voyage Up the River Amazon, with a residency at Pará.[3][4]

Neither had much money, so they determined to fund themselves by collecting and selling fine specimens of birds and insects.[5] Both made extensive travels—in different parts of the Amazon basin—creating large natural history collections, especially of insects. Wallace sailed back to England in 1852 after four years; on the voyage, his ship caught fire, and his collection was destroyed; undeterred, he set out again, leading eventually (1869) to a comparable book, The Malay Archipelago.[6][7][8] By the time he came home in November 1859,[9] Bates had collected over 14,000 species, of which 8,000 were new to science.[5] His observations of the coloration of butterflies led him to describe what is now called Batesian mimicry, where an edible species protects itself from predators by appearing like a distasteful species.[5] Bates's account of his stay, including observations of nature and the people around him, occupies his book.

In the abridged version, there is a balance between descriptions of places and adventures, and the wildlife seen there. The style is accurate, but vivid and direct:

The house lizards belong to a peculiar family, the Geckos, and are found even in the best-kept chambers, most frequently on the walls and ceilings, to which they cling motionless by day, being active only at night. They are of speckled grey or ashy colours. The structure of their feet is beautifully adapted for clinging to and running over smooth surfaces; the underside of their toes being expanded into cushions, beneath which folds of skin form a series of flexible plates. By means of this apparatus they can walk or run across a smooth ceiling with their backs downwards ; the plated soles, by quick muscular action, exhausting and admitting air alternately. The Geckos are very repulsive in appearance.

— Bates, chapter 1.

The book begins and ends suddenly. The journey out, as reviewer Joseph James observes,[10] is dismissed in a few words. The last few lines of the book run:

On the 6th of June, when in 7° 55' N. lat. and 52° 30' W. long., and therefore about 400 miles from the mouth of the main Amazons, we passed numerous patches of floating grass mingled with tree-trunks and withered foliage. Amongst these masses I espied many fruits of that peculiarly Amazonian tree the Ubussu palm; this was the last I saw of the Great River.

— Bates

Illustrations

There are 39 illustrations, some of animals and plants, some of human topics such as the "Masked-dance and wedding-feast of Tucuna Indians", which is signed by Josiah Wood Whymper. Some illustrations including "Turtle Fishing and Adventure with Alligator"[P 2] are by the German illustrator Johann Baptist Zwecker; some, such as "Bird-Killing Spider (Mygale Avicularia) Attacking Finches"[P 3] are by E.W. Robinson; others by the zoological artist Joseph Wolf.[11]

Chapters

The structure of the readable, cut-down second edition of 1864 is as follows:

- 1 Pará — arrival, aspect of the country, etc. (now the city of Belém)

- Bates arrives, and at once starts learning about the country's peoples and natural history.

The impressions received during this first walk can never wholly fade from my mind... Amongst them were several handsome women, dressed in a slovenly manner, barefoot or shod in loose slippers; but wearing richly-decorated ear-rings, and around their necks strings of very large gold beads. They had dark expressive eyes, and remarkably rich heads of hair. It was a mere fancy, but I thought the mingled squalor, luxuriance and beauty of these women were pointedly in harmony with the rest of the scene; so striking, in the view, was the mixture of natural riches and human poverty.

— Bates[P 4]

- He soon notices and describes the leafcutter ants.[P 5] He stays in Pará for 18 months, making short trips into the interior; the city is clean and safe compared to others in Brazil.[P 6]

- 2 Pará — the swampy forests, etc.

- Bates takes a house a few miles outside town on the edge of the forest, and soon starts to notice butterflies and climbing palms. He begins collecting during the day, and making notes and preparing specimens in the evening. At first he is disappointed by how few signs there are of larger animals such as monkeys, tapir or jaguar. Later he realizes these do exist, but are widely scattered and very shy. He meets a landowner who complains of the high price of slaves. There are colossal trees with buttressed trunks.

- 3 Pará — religious holidays, marmoset monkeys, serpents, insects

- He witnesses Catholic processions, notably the festival for Our Lady of Nazareth at Pará. He describes the few monkeys that can be seen in the area, and the strange Amphisbaena, a legless lizard. There are beautiful Morpho butterflies of different species, and assorted spiders, including "monstrous" hairy ones.

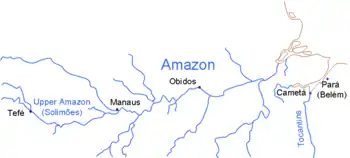

- 4 The Tocantins and Cametá

- Bates and Wallace travel up the Tocantins river, hiring a two-masted boat, a crew of three, and taking provisions for three months. At Baiao he is astonished to be shown a young man's books including Virgil, Terence, Cicero and Livy: "an unexpected sight, a classical library in a mud-plastered and palm-thatched hut on the banks of the Tocantins".[P 7] Their host kills an ox in their honour, but Bates is kept awake by swarms of rats and cockroaches.[P 8] They see the hyacinthine macaw which can crush hard palm nuts with its beak,[P 9] and two species of freshwater dolphin, one new to science.[P 10] Bates visits Cameta; Wallace goes to explore the Guama and Capim rivers.[P 11] The large bird-eating spider (Mygalomorphae) has urticating hairs: Bates handles the first specimen "incautiously, and I suffered terribly for three days". He sees some children leading one with a cord around its waist like a dog.[P 12] On the return journey, the boat with his baggage leaves before him; when he catches up with it, he finds it "leaking at all points".[P 13]

- 5 Caripí and the Bay of Marajó

- Bates stays three months in an old mansion on the coast, going insect-hunting with a German who lives in the woods. His room is full of four species of bat: one leaf-nosed bat, Phyllostoma, bites him on the hip: "This was rather unpleasant".[P 14] He finds stewed giant anteater delicious, like goose.[P 15] Several times he shoots hummingbird hawkmoths, mistaking them for hummingbirds.[P 16] He catches a pale brown tree snake 4 ft 8 in (140 cm) long, but only 1/4 in (6mm) thick, and a pale green one 6 ft (180 cm) long "undistinguishable amidst the foliage".[P 17] When he has shot all the game around his house, he goes hunting with a neighbour by canoe, getting some agouti and paca rodents.[P 18]

- 6 The Lower Amazons — Pará to Obydos (now the city of Óbidos)

- He describes how travellers went upriver before the steamboats arrived, and gives a history of earlier explorations of the Amazons. His preparations for the voyage to Obydos include household goods, provisions, ammunition, boxes, books and "a hundredweight (50 kg) of copper money".[P 19] There are many species of palms along a river channel.[P 20] A rare species of alligator and the armoured Loricaria fish are caught.[P 21] Obydos is a pleasant town of 1200 people, on cliffs of pink and yellow clays, surrounded by cocoa plantations with four kinds of monkey and the huge Morpho hecuba butterfly up to 8 in (20 cm) across, as well as slow-flying Heliconius butterflies in great numbers.[P 22] He obtains a musical cricket, Chlorocoelus tanana.[P 23]

- 7 The Lower Amazons — Obydos to Manaos, or the Barra of the Rio Negro

- Bates leaves Obydos; he finds the people lazy, as otherwise they could easily become comfortable with mixed farming. They sail through a tremendous storm.[P 24] He finds a Pterochroza grasshopper whose forewings perfectly resemble leaves,[P 25] the Victoria waterlily, masses of ticks, the howler monkey and large Morpho butterflies. He meets Wallace again at Barra.[P 26] Back in Para, he catches yellow fever.

- 8 Santarem

- He describes Santarem and the customs of its people. He goes on short "excursions" around the little town. The pure "Indians" choose to build light open shelters, resting inside in hammocks, whereas those of mixed or African origin build more substantial mud huts.[P 27] He enjoys watching small pale green Bembex and other kinds of sand wasps.[P 28] He regrets that the people cut down the Oenocarpus distichus palm to harvest its fruits, which yield a milky, nutty beverage.[P 29] He describes some potter wasps and mason bees.[P 30] He meets a "feiticeira" or witch who knows the uses of many plants, but remarks that "the Indian men all become sceptics after a little intercourse with the whites" and that her witchcraft "was of a very weak quality" though others have more dangerous tricks.[P 31]

- 9 Voyage up the Tapajos

- Bates hires a boat made of stonewood for a three month trip up the Tapajos river. He prepares for the trip by salting meat, grinding coffee, and placing all the food in tin boxes to keep insects and damp out. He buys trade-goods such as fishhooks, axes, knives and beads.[P 32] He witnesses poison-fishing using lianas of Paullinia pinnata.[P 33] At Point Cajetuba he finds a line of dead fire-ants, "an inch or two in height and breadth", washed up on the shore "without interruption for miles".[P 34] Terrible wounds are inflicted by the stingray[P 33] and the piranha.[P 35] His men make a canoe from a trunk of the stonewood tree,[P 36] and an anaconda steals two chickens from a cage on his boat; the snake is "only 18 feet nine inches (6 metres) in length".[P 37] Becoming weak from a diet of fish, he eats a spider monkey, finding it delicious.[P 38] They notice the river is gently tidal, 530 miles (850 km) from its mouth, "a proof of the extreme flatness of the land".[P 39] Bates is unimpressed by a homeopathy-crazed priest,[P 40] especially when his pills prove useless against fever.[P 41]

- 10 The Upper Amazons — Voyage to Ega (now the city of Tefé)

- He sails from Barra (continuing the story from Chapter 7) to Ega. In Solimões (the Upper Amazons) the soil is clay, alluvium or deep humus, with rich vegetation.[P 42] They catch a manatee (sea cow) which tastes like coarse pork with greenish, fish-flavoured fat, and he is badly bitten by small "Pium" bloodsucking flies.[P 43] Pieces of pumice have floated 1200 miles (1900 km) from the Andes volcanoes.[P 44] Bates observes a large landslip on which masses of giant forest trees rock to and fro.[P 45] He notes there are discomforts but "scarcely any danger from wild animals".[P 46] He becomes desperate for intellectual society, running out of reading matter, even the advertisements in the Athenaeum journal.[P 47] He describes the food and fruits at Ega, and the curious seasons, with two wet and two dry seasons each year, the river thus rising and falling twice. The people regularly eat turtles.[P 48]

- 11 Excursions in the Neighbourhood of Ega

- Bates goes hunting with a native, who brings down a crested oropendola with a blowpipe at a range of 30 yards (27 metres); he notes that the usefully silent weapon can kill at twice that range, but that he and Wallace "found it very difficult to hold steady the long tubes".[P 49] Around a campfire, he listens to tales; the Bouto or river dolphin used to take "the shape of a beautiful woman, with hair hanging loose to her heels, and walking ashore at night in the streets of Ega, to entice the young men down to the water" where the Bouto would grab them and "plunge beneath the waves with a triumphant cry".[P 50] They go turtle-hunting; and Bates kills an alligator with a heavy stick.[P 51] He finds many footprints of the jaguar, and "the great pleasure" of seeing the "rare and curious umbrella bird".[P 52] Arrived in Catua, he admires a woman of 17: "her figure was almost faultless", and her blue mouth "gave quite a captivating finish to her appearance", but she was "extremely bashful". He is amazed at how much alcohol the "shy Indian and Mameluco maidens" can drink, never giving way to their suitors without it.[P 53]

- 12 Animals of the Neighbourhood of Ega

- Having discovered over 3000 new species at Ega, Bates agrees that discovery "forms but a small item in the interest belonging to the study of the living creation."[P 54] He describes the scarlet-faced and other monkeys, "a curious animal", the kinkajou, bats, and toucans. He found 18 species "of true Papilio (swallowtail) butterflies" and about 550 butterfly species in all at Ega, among over 7000 species of insect. He describes some unusual insects and their behaviour, including a moth which suspends its cocoon on a long strong silk thread, which while conspicuous is hard for birds to attack.[P 55] He describes at length various species of Eciton or army ants, noting that confused accounts of these have appeared in travel books, then copied into natural histories.

- 13 Excursions beyond Ega

- In November 1856 Bates travels on a steamboat from Ega upriver to Tunantins; it travels all night despite the thick darkness, and makes the 240 miles (380 km) in four days, with the captain at the wheel almost the whole time. He is delighted to discover a new butterfly, Catagramma excelsior, the largest of its genus. He finds the forest at St Paulo glorious, writing that five years would not be enough "to exhaust the treasures of its neighbourhood in Zoology and Botany":[P 56]

At mid-day the vertical sun penetrates into the gloomy depths of this romantic spot, lighting up the leafy banks of the rivulet and its clean sandy margins, where numbers of scarlet, green, and black tanagers and brightly-coloured butterflies sport about in the stray beams. Sparkling brooks, large and small, traverse the glorious forest...

— Bates[P 56]

Reception

Contemporary reviews

Bates, I have read your book — I have seen the Amazons. — John Gould, painter and ornithologist[4]

...the power of observation and felicity of style which characterizes The Naturalist on the Amazons — Alfred Russel Wallace[12]

Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin, having encouraged Bates to publish an account of his travels, read The Naturalist on the River Amazons with great pleasure, writing to Bates on 18 April 1863 that

My criticisms may be condensed into a single sentence, namely that it is the best book of Natural History Travels ever published in England. Your style seems to me admirable. Nothing can be better than the discussion on the struggle for existence & nothing better than the descriptions on the Forest scenery. It is a grand book, & whether or not it sells quickly it will last. You have spoken out boldly on Species; & boldness on this subject seems to get rarer & rarer.— How beautifully illustrated it is. The cut on the back is most tasteful. I heartily congratulate you on its publication.

— Charles Darwin[2]

Darwin noted in his letter that Athenaeum magazine reviewed the book coldly and insolently,[2][13] while the Reader received it warmly.[14] Darwin published An Appreciation of the book in the Natural History Review in 1863,[15] in which he notes that Bates sent back "a mass of specimens" of "no less than 14,712 species" (mostly of insects), of which 8000 were new to science. Darwin at once observes that although Bates is "no mean authority" on insects, the book is not limited to them, but ranges over natural history and more widely to describe his "adventures during his journeyings up and down the mighty river". Darwin clearly enjoyed Bates's account of the hyacinthine macaw, calling it a "splendid bird" with its "enormous beak" able to feed on mucuja palm nuts, and quoting Bates: "which are so hard as to be difficult to break with a heavy hammer, are crushed to a pulp by the powerful beak of this Macaw."[P 9] Darwin took the opportunity to hit back at the Athenaeum magazine which had criticised Bates's book, at the same time painting a picture of Bates's lonely life in the rainforest:[15]

Mr. Bates must indeed have been driven to great straits as regards his mental food, when, as he tells us, he took to reading the Athenaeum three times over, "the first time devouring the more interesting articles—the second, the whole of the remainder—and the third, reading all the advertisements from beginning to end.

— Charles Darwin[15]

Darwin notes that "We need hardly say that Mr. Bates... is a zealous advocate of the hypothesis of the origin of species by derivation from a common stock", in other words that Bates was a staunch Darwinian. Darwin was happy to have the Naturalist on his side, and to use the book in the Origin of Species debate which was still heated in 1863. In particular, Darwin was struck by Bates's robust evidence of mimicry in "the Butterflies of the genus Heliconius".[15] Here Darwin quotes nearly a whole page from Bates's conclusions, including Bates's view of his own findings that hint at speciation actually in progress:[15]

The facts just given are therefore of some scientific importance, for they tend to show that a physiological species can be and is produced in nature out of the varieties of a pre-existing closely allied one. This is not an isolated case... But in very few has it happened that the species which clearly appears to be the parent, co-exists with one that has been evidently derived from it.

— Charles Darwin[15]

London Quarterly Review

The London Quarterly Review began with the observation that "When an intelligent man tells us that he has spent eleven of the best years of his life in any district, we may be pretty sure he has something to say about it which will interest even those who generally find travels dull reading".[16] The reviewer finds Bates among the most readable, and free of the usual "personal twaddle" of travel and adventure books. The reviewer also remarks on Bates's subtitle "...of the origin of species", that Wallace had taken up that theme more fully. In the reviewer's opinion, Bates says little about "the Darwinian hypothesis", focusing instead steadily on natural history, while making "very shrewd remarks" about human society and giving "most glowing" descriptions of tropical scenery. The reviewer notes that most of the people Bates meets "had a tinge of colour" but made the "lonely Englishman" comfortable with their "winning cordiality", and is amused that in a feast in Ega an Indian dressed up as an entomologist, complete with insect-net, hunting-bag, pincushion, and an old pair of spectacles. As for nature, the reviewer considers that "in Brazil man is oppressed, crushed, by the immensity of nature".[16]

Bates's occasional hints at Darwinian evolution are unwelcome or misunderstood by the reviewer, as when Bates writes that if a kind of seed is found in two places, we have to "come to the strange conclusion" it has been created twice unless we can show it can be carried that far; but the reviewer finds Bates in "too great a hurry to come to conclusions" (sic). The reviewer, too, objects to Bates's illustration of "transition forms between Heliconius Melpomene and H. Thelxiope", which he thinks are no more different than "a couple of Dorking hens". Bates's assumption that all forest animals are adapted to forest life is rejected by the reviewer, who sees the same features as signs of a beneficent Creator; while his mention of "slow adaptation of the fauna of a forest-clad country throughout an immense lapse of geological time" is criticised for being "haunted" by this "spectre of time". However the reviewer is fascinated by the variety of life described in the book, and by Bates's "rapturous manner" of speaking about how delicious monkey flesh is, which "almost puts a premium on cannibalism". The review concludes "not without regret" (at such an enjoyable book), and assures readers "that they will not find him heavy reading"; supposes that 11 years was "perhaps a little too much" of tropical life; and recommends intending museum curators to try it for "a year or two".[16]

Joseph F. James

An unabridged edition was reviewed by botanist and geologist Joseph F. James (1857-1897)[17] in Science in 1893.[10] James was reviewing a book which was at that time already a 30-year-old classic that had been reprinted at least four times. He compared it to Gilbert White's 1789 The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle, and Alfred Russel Wallace's The Malay Archipelago, writing that[10]

No one can err, we believe, in placing Bates's "Naturalist on the River Amazons" among the foremost books of travel of this age; and no one who has read it, but recalls its graphic pages with delight.

— Joseph F. James[10]

James notes that "on the appearance of the book in 1868 it met with cordial praise from all quarters". Despite his professed liking for Bates's "direct and concise" style, he quotes at length Bates' description of the tropics, with the[10]

whirring of cicadas, the shrill stridulation of a vast number and variety of field-crickets and grasshoppers, each species sounding its peculiar note; the plaintive hootings of tree-frogs,- all blended together in one continuous ringing sound, - the audible expression of the teeming profusion of nature."

— Joseph F. James[10]

James spends much space in his review quoting Bates's account of the strangling fig, called the "Murderer Liana or Sipo", which he uses to emphasize the "struggle for existence" between plants, as much as for animals. Bates explains how the fig grows rings around the "victim" tree, which eventually dies, leaving the "selfish parasite clasping in its arms the lifeless and decaying body of its victim", so that the fig itself must quickly flower, fruit and die when its support fails. James observes that "It is as much in the reflections that the varied phenomena under observation give rise to as in the descriptive portions that the value and charm of the book lie." Unable to resist a final quotation, even after admitting he has "overstepped our space", he cites Bates's description of his last night in the "country of perpetual summer", regretting he will have to live again in England with its "gloomy winters" and "factory chimneys"; but after Bates has returned, he rediscovers "how incomparably superior is civilized life" which can nourish "feelings, tastes and intellect".[10]

Modern assessments

New Yorker

In 1988, Alex Shoumatoff, writing in The New Yorker, makes Bates's Naturalist his choice if he were allowed only one book for a tropical journey.[4] In his view, it is "the basic text" and a monument of scientific travel writing. Shoumatoff had in fact spent eight months in Bates's "glorious forest" (he quotes) with a copy in his backpack; he thus admires Bates's acceptance of the inevitable discomfort and homesickness from personal knowledge, noting that Bates only complained when all the following had occurred together: he had been robbed, he had gone barefoot having worn out his shoes, he had received no parcels from England, and worst of all he had nothing left to read. But otherwise Bates was "lost in wonder" at the astonishing diversity of the natural history of the Amazons. He was, writes Shoumatoff, one of the four largely self-educated geniuses who pioneered tropical biology, and who all knew each other: Darwin, Wallace, Bates, and the botanist Richard Spruce.[4]

Shoumatoff observes that "Reading Bates is an emotional experience for someone who has travelled in Amazonia, because much of what he describes so poignantly is no longer there"; that the "charm and the genius" of the book is that Bates covers both natural history and everything else that is going on—as the subtitle so accurately says, "A Record of Adventures, Habits of Animals, Sketches of Brazilian and Indian Life, and Aspects of Nature Under the Equator, During Eleven Years of Travel."[4]

He feels a dreamy quality in the best of Bates's writing, as when he meets a boa constrictor: "On seeing me the reptile suddenly turned, and glided at an accelerated rate down the path. ...The rapidly moving and shining body looked like a stream of brown liquid flowing over the thick bed of fallen leaves."[P 57] However he is less impressed with Bates's remarks about the "intellectual inferiority" of the natives, and observes that Bates was wrong about the fertility of tropical soils, which are often poor: the luxuriant growth results from rapid recycling of nutrients. He celebrates the "famous closing passage" of the book, where Bates expresses his "deep misgivings" about returning to England, and writes that recent "progress" in the Amazon is just as shocking.[4]

John G.T. Anderson

In 2011 John G.T. Anderson chose to "recommend the reader's attention" to Bates' Naturalist in the Journal of Natural History Education and Experience, writing that [18]

As much as I love Wallace, I feel that Bates is far and away the better storyteller of the pair, with a keen eye for landscapes, species, and peoples.

— John Anderson[18]

Anderson writes that Bates threw himself eagerly into the local culture, writing warmly about the people as well as delighting in everything from the odd to the mundane "in a modest yet engaging style that leaves this reader itching to go and see for himself." Noting that Bates collected over 8,000 species on the trip, the book shows, writes Anderson, how this was achieved:[18]

the discomfort of narrow canoes, the encounters with alligators and giant spiders, drinking burning rum around a campfire while waiting for jaguars, and above all else the sheer fun and intense joy of seeing new things in new places through eyes of a keen observer and master storyteller..

— John Anderson[18]

Zoological Society of London

The Zoological Society of London writes that "This fascinating, lucidly written book is widely regarded as one of the greatest reports of natural history travels." It describes the book as "an eloquently written compendium of curious natural facts and observations on Amazon life before the rubber boom, revealing the amazing zoological and botanical richness of the region" and calls his specimens "a hugely significant contribution to zoological discovery."[11]

In science, education, and literature

Bates's book is cited in papers for its accurate early observations, such as of the urticating hairs of tarantulas,[19] the puddle drinking habits of butterflies,[20] or of the rich insect fauna in the tropics.[21] The book and Bates' Amazon trip are covered in lecture courses on evolution by professors such as Anne E. Magurran and Maria Dornelas.[22] The warm reception of Bates's Naturalist was not confined to scientists. The novelists D.H. Lawrence and George Orwell both wrote admiringly of the book.[23] Lawrence wrote to his friend S. S. Koteliansky "I should like, from the Everyman Library Bates' – Naturalist on the Amazon... because I intend some day to go to South America – to Peru or Ecuador, not the Amazon. But I know Bates is good."[24]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Bates was 22, Wallace was 24.

References

Primary

- ↑ Bates, 1864. page xv.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 359.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 97.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. pp. 10–14.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 23.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 75.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. pp. 76–77.

- 1 2 Bates, 1864. pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 88.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 89.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. pp. 95–97.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 108.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 109.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 115.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 116.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 124.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 135.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 139.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 149.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. pp. 165–167.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 170.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 201.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 219.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. pp. 221–223.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. pp. 224–225.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. pp. 225–229.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 234.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 238.

- 1 2 Bates, 1864. p. 242.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 244.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 247.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 265.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 262–263.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 266.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 269.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 250.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 281.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 290.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 295–296.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 298.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 300.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 307.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 308.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. pp. 326–330.

- 1 2 Bates, 1864. pp. 338–340.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 357.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 358.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. pp. 374–375.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. pp. 366–367.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 388.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 414.

- 1 2 Bates, 1864. p. 447.

- ↑ Bates, 1864. p. 267.

Secondary

- 1 2 Mallet, Jim. "Henry Walter Bates". University College London. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 Darwin, Charles (18 April 1863). "Darwin to Bates, H.W." Letter 4107. Darwin Correspondence Project. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ Edwards, 1847.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Shoumatoff, Alex (22 August 1988). "A Critic at Large, Henry Walter Bates". New Yorker: 76. Archived from the original on 6 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 Dickenson, John (July 1992). "The Naturalist on the River Amazons and a Wider World: Reflections on the Centenary of Henry Walter Bates". The Geographical Journal. 158 (2): 207–214. doi:10.2307/3059789. JSTOR 3059789.

- ↑ Shermer, Michael (2002). In Darwin's Shadow: The Life and Science of Alfred Russel Wallace. Oxford University Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-19-514830-4.

- ↑ Slotten, Ross A. (2004). The Heretic in Darwin's Court: the life of Alfred Russel Wallace. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 84–88. ISBN 0-231-13010-4.

- ↑ Wallace, 1869.

- ↑ "Henry Walter Bates". The Linnean Society. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 James, Joseph F. (24 March 1893). "The Naturalist on the River Amazons. BY HENRY WALTER BATES. With a memoir of the author by Edward Clodd. Reprint of the unabridged edition. New York. D. Appleton & Co. 395 p. Map. 8°". Science. ns-21 (529): 163–165. doi:10.1126/science.ns-21.529.163-b.

- 1 2 "Artefact of the month - June 2007". Zoological Society of London. June 2007. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ↑ Wallace, Alfred Russel (25 February 1892). "H. W. Bates, The Naturalist of the Amazons". Nature. 45 (1165): 398–399. Bibcode:1892Natur..45..398A. doi:10.1038/045398c0.

- ↑ "Athenaeum". Review of The naturalist on the River Amazons. 25 April 1863. p. 489.

- ↑ "Reader". Review of The naturalist on the River Amazons. 18 April 1863. p. 378.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Darwin, Charles (1863). "An Appreciation: The Naturalist on the River Amazons by Henry Walter Bates". Natural History Review, vol iii. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 Telford, John; Barber, Benjamin Aquila, eds. (1864). "Book Reviews: The Naturalist on the River Amazons". London Quarterly Review. 22: 48–71.

- ↑ Vincent, Michael A. "A history of Miami University Department of Botany" (PDF). Prehistory (before 1906). Miami University. p. 6. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Anderson, John GT (2011). "Journal of Natural History Education and Experience, Volume 5" (PDF). 101 Natural History Books That You Should Read Before You Die: 2. Henry Walter Bates' The Naturalist on the River Amazons. Natural History Network. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ Foelix, Rainer; Rast, Bastian; Erb, Bruno (2009). "Palpal urticating hairs in the tarantula Ephebopus: fine structure and mechanism of release" (PDF). Journal of Arachnology. 37 (3): 292–298. doi:10.1636/sh08-106.1. S2CID 55161327.

- ↑ Scribner, J Mark (Spring 1987). "Puddling By Female Florida Tiger Swallowtail Butterflies, Papillo Glaucus Australis (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae)" (PDF). The Great Lakes Entomologist. 20 (1): 21–24.

- ↑ Magurran, Anne E; Dornelas, Maria (November 2010). "Biological diversity in a changing world". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 365 (1558): 3593–3597. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0296. PMC 2982013. PMID 20980308.

- ↑ Carroll, Sean B. (2005). "Evolution: Constant Change and Common Threads 2005 Holiday Lectures on Science" (PDF). HHMI. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ Slater, Candace (2002). Entangled Edens: Visions of the Amazon. University of California Press. p. 235. ISBN 9780520226418.

- ↑ Lawrence, D.H. (2006). The Letters of D.H. Lawrence. Cambridge University Press. p. 315. Letter 1681 of 1 January 1919.

Bibliography

- Bates, H. W. (1863). The naturalist on the River Amazons, a record of adventures, habits of animals, sketches of Brazilian and Indian life and aspects of nature under the Equator during eleven years of travel. London: J. Murray. (First edition.)

- --- Second edition, 1864. (Reprinted in paperback facsimile, Elibron Classics, 2005.)

- Edwards, William Henry (1861). A voyage up the River Amazon: including a residence at Pará. J. Murray.

- Wallace, Alfred Russel (1869). The Malay Archipelago: The land of the orang-utan, and the bird of paradise. A narrative of travel, with sketches of man and nature (1 ed.). Macmillan.

External links

- The Naturalist on the River Amazons at Project Gutenberg

- First edition (1863) in 2 volumes, Murray, London. Volume 1; Volume 2.

- Reprint of 2nd (abridged, 1864) edition (Dent, London; Dutton, New York) (with 'Appreciation' by Charles Darwin)

- 1892 Edition, single volume, with a Memoir of the Author by Edward Clodd.