Ngola Ritmos | |

|---|---|

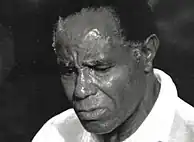

Liceu Vieira Dias, Nino Ndongo, Belita Palma, Amadeu Amorim, Lourdes Van Dunem and Zé María | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Bairro Operário, Luanda, Angola |

| Genres | Afro-Folk Semba |

| Instrument(s) | Guitar, Reco-Reco (Dikanza), Ngoma Drums, Accordion and Acacia Sticks |

| Years active | 1947–1968 |

| Past members | Carlos Aniceto Vieira Dias (Liceu), Domingos Van-Dunem, Mário da Silva Araújo, Francisco Machado, Manuel António Rodrigues (Nino Ndongo), Amadeu Timóteo Malheiros Amorim (Amadeu Amorim), Euclides Fontes Pereira Rocha (Fontinhas), José Maria dos Santos (Zé Maria), José Cordeiro dos Santos (Zé Cordeiro), Ricardo Vaz Borja (Xodó), José Ferreira (Gegé), Lourdes Van-Dunem and Belita Palma |

Ngola Ritmos was a musical group created in 1947 in the home of Manuel dos Passos by a group of young men called Domingos Van-Dúnem, Mário da Silva Araújo, Francisco Machado, Liceu Vieira Días and Nino Ndongo who formerly comprised a group named "Os Sambas" . They sang in kimbundu with the purpose to spread and divulge cultural and political awareness to the peoples of Luanda during the Portuguese Empire era. They felt a need to create something new. To spread and divulge folkloric themes that were fading away due to colonialism so Ngola Ritmos, still a small group, appeared with Liceu Vieira Días as the main guitar player and the rest playing with drums and acacia sticks as rattles.[1]

Musical career

In the 1950s, the band comprised Liceu, Nino, Amadeu , José Maria, Euclides Fontes Pereira, José Cordeiro, Lourdes Van-Dúnem and Belita Palma. They sang laments inspired by their daily chronicles or funeral rites where women would also sing laments.[2]

They recorded two discs[3] and in 1965 they performed for the first time in a big city.[4]

While songs like Mbiri Mbiri, Kolonial, Palamé or Muxima, which are their most popular themes, have been covered by numerous artists, recordings by Ngola Ritmos are very rare. Muxima and Django Ué were recorded in Luanda. Most of the members of Ngola Ritmos were nationalist militants. Liceu, one of the founding members of the group, was also a founding member of the MPLA and along with Amadeu Amorim, he was arrested in 1959 and deported to the Tarrafal prison in Cape Verde, to return only ten years later. Nevertheless, the band lasted until the late sixties, recording the song Nzaji in Lisbon.[5]

Political involvement

They made their first public appearance with original sounds that at the time were some very popular cultural repertoires. They *raised* musical manifestations linked to the terrible reality of the time in which they lived in with a concern for recreation but also with the hope of transmitting through music the political and economic reality of their country, Angola.[6] Undoubtedly, this work was an awakening of consciences because at the time they rarely had the opportunity to hear Angolans play in shows. They took great pride in this because they had finally taken their music to the neighbourhoods, the musseques as they called them to help their society to reclaim their social and cultural values and revert from colonially imposed norms to their own.[7][8]

And so they kept making music behind the backs of the portuguese in the musseques and even more artists of which Belita Palma, Lurdes Van-Dúnem, Fontinhas, Zé Maria, Amadeu Amorim, Zé Cordeiro, Xodó and Gégé. Belita Palma became the main singer along with Lourdes Van-Dunem, seen as they were the most talented. But one day after multiple years of success Nino, Liceu and Amadeu, caught by the police that at the time was called PIDE, were taken to the Tarrafal concentration camp. Fortunately this didn’t stop the group from evolving and continue to make music seen as they went on yo play songs such as “A Moringa”, “Muxima”, “Nzagi” etc … and they went on to become famous folkloric songs among Angolans. Their music fit so well with theatre because they sang laments and stories about what their people went through in the slums.

They had to gain a new form and to create a new branch of the group by making an experimental theatre group/ drama club called 'Gexto'[9] so they recruited more members, partial members, to be the actors who would serve as hosts for every time they were performing while they still played music. This was one of the first early ways to amplify art in every single way possible in Luanda. That’s where Angola’s contact with Cuba started and it was because of Ngola Ritmos. Francisco Javier Hernández, first cuban internationalist went to Luando as a missionary in 1988 as first cuban ambassador to commune with any Angolan representative of music and culture and get to know angolan culture, to help simultaneaously exchange cultural opinions and traditions and spread Angolan culture not only with Cuba but also on a global aspect.

"Liceu Vieira Dias and Ngola Ritmos were de facto pioneers of the aesthetic modernity of Angolan Popular Music, in the sense of innovative proposals for the stylization of the popular songbook, and the Ngola Ritmos ensemble proved to be one of the paradigms of Angolan nationalism, a phenomenon embodied, fundamentally , in musical intervention, in an evident perspective of alertness and emancipation of political and cultural conscience, as did, in a clearly mobilizing dimension, the Kimbambas do Ritmo and Nzaji ensembles, in the beginnings of the national liberation struggle."

"The first meetings and gatherings that shaped the group Ngola Ritmos, frequent on Saturday and Sunday afternoons, took place in the mid-1940s, at the home of the nationalist, Manuel dos Passos, where Liceu Vieira Dias, Domingos Van-Dúnem , Mário da Silva Araújo, Francisco Machado and Manuel António Rodrigues, Nino Ndongo. Later, in 1951, Euclides Fontes Pereira joined the group, Fontinhas, composer and owner of a very peculiar subtlety of friction of the “dikanza”, reco-reco, and, later, the guitarist and interpreter, José Maria dos Santos, Zé Maria. The hard core of Ngola Ritmos was formed by Euclides Fontes Pereira, Fontinhas, Amadeu Timóteo Malheiros Amorim, Amadeu Amorim, Liceu Vieira Dias, Liceu, José Maria dos Santos, Zé Maria, and Manuel António Rodrigues, Nino Ndongo. In its final stage, Ngola Ritmos had the helpful collaboration of Belita Palma, Lourdes Van-Dúnem and Conceição Legot, who would form the 'Trio Femeníno'.[10]

The term Massemba, a popular umbigada dance, performed by couples of dancers in a group, is plural of semba, the name that came to designate the most representative musical genre in the region of Luanda. Danced in the street, on recess afternoons and moonlit nights, the Massemba, passed to the virtuosity of the guitars of Liceu Vieira Dias, José Maria and Nino Ndongo, giving rise to semba. Massemba took on the Portuguese name of rivet, when it migrated to the dance halls with the support of the concertina. irregular beat" by Liceu Vieira Dias and semba, by the innovative proposals of José Maria and Nino Ndongo, in their most varied known rhythmic figures. Semba, through the rhythmic proposals of José Maria and Nino Ndongo, came to be absorbed, in a line of continuities, by important later guitarists such as José Keno, from Jovens do Prenda, who says he was influenced by the generality of the music of Ngola Ritmos, Duia , ensembles by Gingas, Marito Arcanjo, Kiezos, the song “Rosa Rosé” and “Muá Pangu”, are two examples, Botto Trindade, from Bongos, guitarist who inherited the rhythm of Ngola Ritmos, through Carlitos Vieira Dias, son of Liceu Vieira Dias, Manuel Marinheiro, África Ritmos, Mingo, Jovens do Prenda, and Ângelo Manuel Quental, from the group Águias Reais."

Tributes

- In 1978 António Ole made the film about the group entitled 'O Ritmo do N'Gola Ritmos' [5][11]

- In 2009 the film 'O Lendário Tio Liceu e os N'gola Ritmos' , by Jorge António, received the Award Best Documentary at FICLuanda 2010

- Semana de Homenagem a Liceu Vieira Dias e ao Ngola Ritmos[10]

- Live performance in hommage to Ngola Ritmos

- Toty Sa'Med,[12] Aline Frazão,[13] Ruy Mingas,[14] Show do Mês,[15] and more, contributing to the perpetuation of Liceu Vieira Dias and Ngola Ritmos by interpreting song by them.

See also

References

- ↑ "Mário Rui Silva e o Ngola Ritmos | Música | Cultura | Jornal de Angola - Online". 2017-12-01. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ↑ Boulbina, Seloua Luste (2012). "Présence africaine de la musique et culture nationale "Tribute to Fanon"". Présence Africaine. 185–186 (185/186): 219–229. doi:10.3917/presa.185.0219. ISSN 0032-7638. JSTOR 24431127.

- ↑ "N'gola Ritmos". Discogs. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ↑ A.cortez (2011-04-11). "Música Eléctrica a Preto e Branco: N' Gola Ritmos". Música Eléctrica a Preto e Branco. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- 1 2 O Ritmo do Ngola Ritmos, retrieved 2022-11-23

- ↑ Moorman, Marissa Jean (2008). Intonations: A Social History of Music and Nation in Luanda, Angola, from 1945 to Recent Times. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-1823-9.

- ↑ Minnesota Monographs in the Humanities. University of Minnesota Press. 1975. ISBN 978-0-8166-0745-7.

- ↑ "N'gola Ritmos - Do ritmo e da palavra se fez luta". Afreaka (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2014-12-25. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ↑ Moorman, Marissa Jean (2004). Feel Angolan with this Music: A Social History of Music and Nation, Luanda, Angola 1945-1975. University of Minnesota.

- 1 2 "Jornal de Angola - Notícias - Semana de homenagem a Liceu Vieira Dias e Ngola Ritmos". Jornal de Angola (in Portuguese). 2019-05-06. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ↑ "You are being redirected..." kadist.org. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ↑ "Toty Sa´Med recupera os clássicos da música angolana". VOA (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ↑ Aline Frazão - Susana/Nguxi (Live in Tivoli BBVA) ft. Toty Sa'Med, retrieved 2023-01-21

- ↑ Ruy Mingas e Carlitos - Homenagem ao tio - Cantar Ruy Mingas, retrieved 2023-01-21

- ↑ SHOW DO MÊS 6ª TEMPORADA - CANTAR - RUY MINGAS, retrieved 2023-01-21