| Neretva | |

|---|---|

| |

Neretva Delta  Neretva (Dinaric Alps) | |

| Etymology | of Illyrian origin, from Indo-European base *ner-, *nor- "to dive, dip, immerse" |

| Location | |

| Countries | |

| Towns | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Lebršnik and Zelengora Mountains, Dinaric Alps, Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| • coordinates | 43°16′17″N 18°33′27″E / 43.27139°N 18.55750°E |

| • elevation | 1,227 m (4,026 ft) |

| Mouth | Adriatic Sea |

• location | Ploče, Croatia |

• coordinates | 43°01′11″N 17°26′42″E / 43.01972°N 17.44500°E |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 225 km (140 mi)[1] |

| Basin size | 11,798 km2 (4,555 sq mi)[1] |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 341 m3/s (12,000 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Progression | Neretva→ Adriatic Sea |

| River system | Adriatic |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Mostarska Bijela, Buna, Bregava, Krupa |

| • right | Rakitnica, Rama, Trebižat |

| Waterbodies | Uloško Lake, Boračko jezero, Blatačko Lake, Jablaničko Lake, Ramsko Lake, Salakovačko Lake, Grabovičko Lake, Mostarsko Lake, Hutovo Blato, Vrutak, Neretva Delta |

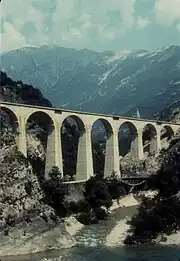

| Bridges | Stara Ćuprija, Stari Most |

| Inland ports | Metković |

The Neretva (Serbian Cyrillic: Неретва, pronounced [něreːtʋa]), also known as Narenta, is one of the largest rivers of the eastern part of the Adriatic basin. Four hydroelectric power plants with large dams (higher than 150,5 metres)[2] provide flood protection, power and water storage. It is recognized for its natural environment and diverse landscapes.[3]

Freshwater ecosystems have suffered from an increasing population and the associated development pressures. One of the most valuable natural resources of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia is its freshwater resource,[4] contained by an abundant wellspring and clear rivers.[4][5] Situated between the major regional rivers (Drina river on the east, Una river on the west and the Sava river) the Neretva basin contains the most significant[4] source of drinking water.

The Neretva is notable[6][7] among rivers of the Dinaric Alps region, especially regarding its diverse ecosystems and habitats, flora and fauna, cultural and historic heritage.[4][5]

Its name has been suggested to come from the Indo-European root *ner, meaning "to dive". The same root is seen in the Serbo-Croatian root "roniti".[8]

Geography and hydrology

The Neretva flows through Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia until reaching the Adriatic Sea. It is the largest karst river in the Dinaric Alps in the eastern part of the Adriatic basin/watershed. Its total length is 225 kilometres (140 miles), of which 208 kilometres (129 miles) are in Bosnia and Herzegovina, while the final 22 kilometres (14 miles) are in the Dubrovnik-Neretva County of Croatia.[9]

The Neretva watershed is 11,798 square kilometres (4,555 sq mi) in total; in Bosnia and Herzegovina 11,368 square kilometres (4,389 sq mi) with the addition of the Trebišnjica river watershed and in Croatia, 430 square kilometres (170 sq mi).[1] The average discharge at profile Žitomislići in Bosnia and Herzegovina is 233 cubic metres (8,200 cu ft)/s and at the mouth in Croatia is 341 cubic metres (12,000 cu ft)/s in addition to the Trebišnjica River's 402 cubic metres (14,200 cu ft)/s. The Trebišnjica River basin is included in the Neretva watershed due to a physical link of the two basins by the porous karst terrain.

The hydrological parameters of Neretva are regularly monitored in Croatia at Metković.[10]

Sections

.jpg.webp)

Geographically and hydrologically the Neretva is divided into three sections.[11]

Its source and headwaters gorge are situated deep in the Dinaric Alps at the base of the Zelengora and Lebršnik mountains, specifically under the Gredelj saddle. The river source is at 1,227 meters above sea level and consists of five small and distinct wellsprings. On its 90 kilometers course through the first section the Neretva cuts two distinct deep and narrow canyons and two distinct wide and fertile valleys, around Ulog and then Župa Komska, wider area around Glavatičevo, before it reaches town of Konjic. This section is also better known as the Upper Neretva (Bosnian: Gornja Neretva), and here river flows generally from east-southeast to north-northwest as do most Bosnia and Herzegovina rivers belonging to the Danube watershed, and covers some 1,390 square kilometres (540 sq mi) with an average elevation of 1.2%. Right below Konjic, the Neretva again expands into a third and largest valley which provided fertile agricultural land before it was flooded by large artificial reservoir, Jablaničko Lake, formed after construction of a Jablanica Dam near town of Jablanica.[11][12]

The second section begins from the confluence of the Neretva and the Rama between Konjic and Jablanica where the Neretva suddenly takes almost 180° degrees turn toward east-southeast and flows the short leg before reaches town of Jablanica, from which point turns again toward south. From Jablanica, the Neretva enters third and the largest canyon on its course, running through the steep slopes mountains of Prenj, Čvrsnica and Čabulja reaching 800–1,200 metres (2,625–3,937 feet) in depth. Three hydroelectric dams operate between Jablanica and Mostar.[12]

When the Neretva expands for the second and final time, it reaches its third section. This area is often colloquially called the "Bosnian and Herzegovinian California". The last 30 kilometres (19 miles) of its course forms wide alluvial delta, before the river empties into the Adriatic Sea.[13]

Tributaries

Rivers of the Tatinac (also known as the Jezernica), the Gornji Krupac and Donji Krupac, the Ljuta (also known as the Dindolka), the Jesenica, the Bjelimićka Rijeka, the Slatinica, the Račica, the Rakitnica, the Ljuta (Konjička), the Trešanica, the Neretvica, the Rama, Doljanka, the Drežanka, the Grabovica, the Radobolja, and the Trebižat flow into the Neretva from the right, while the Jezernica, the Živanjski Potok (also known as the Živašnica), the Lađanica, the Krupac, the Bukovica, the Šištica with its Šištica Waterfall, the Bijela, the Idbar, the Glogošnica, the Mostarska Bijela, the Buna, the Bregava, and the Krupa flow into it from the left.

Towns and villages

Towns and villages on the Neretva include Ulog, Glavatičevo, Konjic, Čelebići, Ostrožac, Jablanica, Grabovica, Drežnica, Bijelo polje, Vrapčići, Mostar, Buna village, the historical town of Blagaj, Žitomislići, the historical village of Počitelj, Tasovčići, Čapljina, and Gabela in Bosnia and Herzegovina; and Metković, Opuzen, Komin, Rogotin, and Ploče in Croatia. The biggest town on the Neretva River is Mostar in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Upper Neretva

.jpg.webp)

The upper course of the Neretva river is simply called the Upper Neretva (Bosnian: Gornja Neretva). It includes numerous streams and well-springs, three major glacial lakes near the river and more lakes scattered across the mountains of Treskavica and Zelengora in the wider area, mountains, peaks and forests, flora and fauna of the area. The Upper Neretva has water of Class I purity[14] and is almost certainly the coldest river water in the world, often as low as 7–8 degrees Celsius in the summer months. Rising from the base of the Zelengora and Lebršnik Mountain, Neretva headwaters run in undisturbed rapids and waterfalls, carving steep gorges reaching 600–800 metres (2,000–2,600 ft) in depth.

Rakitnica River

The Rakitnica is the main tributary of the first section (Bosnian: Gornja Neretva). The Rakitnica River forms a 26 km (16 miles) long canyon, out of its 32 km (20 miles) length, that stretches between Bjelašnica and Visočica to the southeast from Sarajevo.[15] From the canyon, a hiking trail along the ridge of the Rakitnica canyon drops 800 m below, to the famous village of Lukomir. The village is the only remaining traditional semi-nomadic Bosniak mountain village in Bosnia and Herzegovina. At almost 1,500 m, Lukomir features stone homes with cherry-wood roof tiles. It is the country's highest and most isolated mountain village. The village is inaccessible from the first snows in December until late April and sometimes even later, except by skis or on foot.

Middle Neretva

Hydrographically the Middle Neretva section begins from the town of Konjic, but after the construction of Jablanica Hydroelectric Power Station and flooding of the large fertile valley between Konjic and Jablanica, known simply as "Neretva" since Middle Ages. The new point for hydrographical division became the dam of the Jablanica HPP where there also is a place of confluence of the rivers Neretva and Rama. Here the Neretva river suddenly takes an almost 180° turn towards the east-southeast and flows for a short leg before it reaches the town of Jablanica. From this point it turns again toward the south and enters the third and largest canyon on its course, running through the steep slopes of the mountains of Prenj, Čvrsnica, and Čabulja, reaching between 800–1,200 metres (2,625–3,937 feet) in depth. This section is characterized by a steep and relatively narrow canyon, and rugged karstic geology and hydrology.

Four enormous vale-size rifts appear in the mountainsides forming canyon walls, two from each side of the river, intersecting with the main canyon almost perpendicularly. The Neretva receives only four small streams in this section, all running through these side vales, which are relatively short. Going downstream from Jablanica, the first two from each side are the Glogošnica stream, its eponymous canyon and small village on the left, and the Grabovica stream with its eponymous canyon and historical village, from the right side. Further downstream two much larger vales appear again on each side, first on the right the stream of Drežanka and its large and steep valley, with two eponymous villages, Donja (Lower) and Gornja (Upper) Drežnica, and than Mostarska Bijela, as one of the most pristine vales in Bosnia and Herzegovina, with its eponymous uniquely characteristic subterranean stream, embedded deep into the Prenj mountain, on the left.

Although these streams are of low outflow, there are also numerous wellsprings rising on both sides of the canyon at the river banks, with high-capacity discharge. Three large hydroelectric power stations operate in this section of the Neretva, between Jablanica and Mostar, namely Grabovica HPP, Salakovac HPP and Mostar HPP.[12]

Lakes

Jablanica lake is a large artificial lake on the Neretva river, right below Konjic where the Neretva expands into a wide valley. The river provided fertile, agricultural land before the lake flooded most of it. The lake was created in 1953 after construction of a largegravitational hydroelectric dam near Jablanica in central Bosnia and Herzegovina. The lake has an irregular, elongated shape, and its width varies along its length. The lake is a popular vacation destination.[2]

Lower Neretva

Downstream from the confluence of its tributaries, the Trebižat and Bregava Rivers, the valley spreads into an alluvial fan covering 20,000 hectares (49,000 acres). The upper valley, the 7,411 hectares in Bosnia and Herzegovina, is called Hutovo Blato.

Hutovo Blato wetlands

The Neretva Delta has been recognised as a Ramsar site since 1992, and Hutovo Blato since 2001. Both areas form one integrated Ramsar site that is a natural entity divided by the state border.[3] The Important Bird Areas programme, conducted by Birdlife International, covers protected areas in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[16]

Since 1995, Hutovo Blato has been protected as Hutovo Blato Nature Park[17][18] and managed by a public authority. The whole zone is protected from human impact and provides habitat for many plants and animals.[16] The historical site Old Fortress Hutovo Blato is in the Nature Park.

Gornje Blato-Deransko Lake is supplied by the karstic water sources of the Trebišnjica River, emerging from bordering hills. It is hydro-geologically connected to the Neretva River through its effluent, the Krupa River, formed out of five lakes (Škrka, Deranja, Jelim, Orah, Drijen). Large portions are permanently flooded and isolated by wide groves of reedbebds and trees. It represents a more interesting preserved area.[18]

Krupa River

The Krupa River is a Neretva left tributary and the main water current of Hutovo Blato, which carries the waters from Gornje Blato and Svitavsko Lake into the Neretva River. The length of Krupa is 9 km (6 miles) with an average depth of 5 metres (16 feet). The Krupa does not have a specific source, but is an arm of Deransko Lake. Also, the Krupa is a unique river in Europe, because it flows both ways. It flows both towards and back from its mouth. This happens when a high water level causes Neretva to push Krupa in the opposite direction.[18]

Neretva Delta wetlands

Passing towns and villages in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Neretva spills out into the Adriatic Sea, building a wetland delta that is listed under the Ramsar Convention as internationally important.[19][16]

In this lower alluvial valley in Croatia, the Neretva River splinters into multiple courses, creating a delta covering approximately 12,000 hectares. The delta in Croatia has been reduced by extensive land reclamation projects, reducing the river flows to just three branches from the original twelve. The marshes, lagoons and lakes that once dotted this plain have disappeared and only fragments of the old Mediterranean wetlands survive.[20] Wetlands, marshes and lagoons, lakes, beaches, rivers, hummocks (limestone hills) and mountains compose the delta, with five protected areas with a total area of 1,620 ha. These are ornithological, ichthyologic and landscape reserves.[20]

Endemic and endangered species

Dinaric karst water systems support 25% of the total of 546 fish species in Europe, many endemic. The Neretva River, together with four other areas in the Mediterranean, has the largest number of threatened freshwater fish species.[21] The degree of endemism in the karst ecoregion is greater than 10%. Multiple fish species have small habitats and are vulnerable, so they are included on the Red List of endangered fish as of 2006. The Adriatic basin has 88 species of fish, of which 44 are Mediterranean endemic species, and 41 are Adriatic endemic species. More than half of the Adriatic river basin species of fish inhabit the Neretva, the Ombla, the Trebišnjica, the Morača Rivers and their tributaries, and more than 30 are endemic.[22]

Invasive species

A pike perch (Sander lucioperca Linnaeus 1758)[23] (also see Sander (genus)) population in the Neretva River watershed was observed in 1990 for the first time. The Rama River, a right tributary of the Neretva, and its Rama Lake received an unknown quantity of this allochthonous species. Population estimates have increased in the Neretva accumulation lakes. This fact confirms previous scientific assumptions of Škrijelj (1991, 1995), who predicted the possibility of pike perch displacement (migration) from Ramsko Lake to the Rama River and then further downstream to the river and its lakes. In 1990 the perch population made up 1.95% of the fish population in Rama Lake. Within a decade this rose to 25.42% in the nearby Jablaničko Lake.

The fast pace of pike perch population growth and displacements is expected to match the environmental conditions from the mid-ecological valence of this fish. In this sense, it is the established continuous and accelerated growth of the population dynamics of pike perch in Jablaničko Lake, a relatively good representation in Salakovačko Lake and the beginning of growth of population in Grabovičko Lake. Parallel with the increase in pike perch is a decrease in endemic indigenous species like European chub also white chub (Squalius cephalus), and the disappearance of rare and endemic species like Adriatic Dace also Balkan dace (Squalius svallize also Leuciscus svallize Heckel & Kner 1858), Neretvan softmouth trout (Salmothymus obtusirostris oxyrhinchus Steind.) and marble trout (Salmo marmoratus Cuv.).

Pike perch causes clearly visible, negative effects on the autochthonous species in Jablaničko Lake. In Salakovačko Lake these effects are in progress, although less visible, while in Grabovičko Lake it is not yet clearly visible.

Salmonids

Salmonid fish from the Neretva basin show considerable variation in morphology, ecology and behaviour.[24][25]

Among most endangered are three endemic species of trout: Neretvan softmouth trout (Salmothymus obtusirostris oxyrhinchus Steind.),[26] Toothtrout (Salmo dentex)[27] and marble trout (Salmo marmoratus Cuv.).[28]

All three endemic trout species of the Neretva are endangered, mostly due to the habitat destruction or construction of large/major dams ("large" is higher than 15–20 m; "major" is over 150–250 m).[2] Other problems include hybridization or genetic pollution with introduced, non-native trouts, illegal fishing and poor water and fisheries management.[29][30]

Cyprinids

The most endangered cyprinids (family Cyprinidae) are endemic.

Especially interesting are five Phoxinellus (sub)species that inhabit isolated karstic plains (fields) of eastern as well as western Herzegovina in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which eventually reach the Neretva watershed and/or coastal drainages of south-eastern Dalmatia.

- Karst minnow (Phoxinellus metohiensis) is considered Vulnerable (VU).

- South Dalmatian minnow (Phoxinellus pstrossii) is threatened, but was marked Data Deficient (DD) and was not designated on IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Version 2009.1.

- Dalmatian minnow (Phoxinellus ghetaldii) is considered vulnerable.

- Adriatic minnow (Phoxinellus alepidotus) is endemic to Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia and occurs in lowland water bodies with little current. It is threatened due to pollution and habitat destruction.[31] It is considered endangered.

- Spotted minnow (Phoxinellus adspersus), is endemic in the Tihaljina River, which is fed by underground waters from Imotsko field and is connected to the Trebižat river via the Mlada River. It also occurs in Mostarsko Blato wetlands. Fish were found in the source of the Norin River, a right-hand tributary of the lower Neretva at Metković, in Croatia, at Kuti Lake, a left-hand tributary of the lower Neretva, at Imotsko field in Red Lake (Croatia) and the Vrljika river drainage and near Vrgorac in the Matica River system.[32] It is considered vulnerable.

- Minnow nase (Chondrostoma phoxinus) is considered Critically Endangered (CR)

- Neretvan nase (also Dalmatian nase and Dalmatian soiffe) (Chondrostoma knerii)[33] is endemic to the Neretva. Neretvan nase is mainly distributed in the lower parts and delta, the Krupa River, Nature Park Hutovo Blato wetlands and Neretva Delta wetlands. It occurs in water bodies with little current. It is threatened by habitat destruction and pollution.[34] It is considered Vulnerable (VU).

- Adriatic dace also Balkan dace (Squalius svallize also Leuciscus svallize Heckel & Kner 1858)[35] is a vulnerable endemic, although also found in Montenegro and Albania. Adults inhabit water bodies on the low plains, with little current and in lakes. They feed on invertebrates. It is threatened due to pollution, habitat destruction and due to introduction of other species.

- Illyrian dace (Squalius illyricus also Leuciscus illyricus Heckel & Kner 1858)[36] inhabits karstic waters of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Albania. It occurs in water courses on low plains, with little current. It feeds on invertebrates. It is stressed by habitat destruction, pollution and introduced species. It is considered Near Threatened (NT).

- Turskyi dace (Leuciscus turskyi also Squalius turskyi turskyi and Telestes turskyi)[37] inhabits karstic waters, lake Buško Blato and the Krka and Čikola rivers. It occurs on the low plains, with little current and in lakes. It feeds on invertebrates. Threats include water abstraction and pollution. It is considered Critically Endangered (CR).

- Dalmatian barbelgudgeon (Aulopyge hugeli)[38] inhabits karstic streams of Glamocko field, Livanjsko field and Duvanjsko field, lakes Buško Blato, Blidinje and Cetina, Krka and Zrmanja river drainages. It occurs in lentic waters and feeds on plants. The fish is threatened by water pollution and habitat destruction and is considered endangered. It is migratory in Livanjsko field.

Cobitidae

The Neretvan spined loach (Cobitis narentana Karaman, 1928) is an Adriatic watershed endemic that inhabits a narrow area of the Neretva watershed in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[39] In Bosnia and Herzegovina it inhabits only the lower Neretva and its smaller tributaries like the Matica River. In Croatia it is a strictly protected species and inhabits only the Neretva delta and its smaller tributaries, the (Norin) and lake systems of the Neretva delta (Baćina lakes, Kuti, Desne, Modro oko).[39] It is considered Vulnerable (VU).

Neretva delta endemics

The Neretva delta hosts more than 20 endemic species, of which 18 are endemic to the Adriatic watershed, along with three endemic species in Croatia. Nearly half (45%) of the total number of species that inhabit this area are included in one of the categories of threat and are mainly endemic.[22]

Hydroelectric controversy

The benefits brought by hydroelectric dams have come at an environmental and social cost.[40] The waters of the Neretva river with its two main tributaries, the Rama and the Trebišnjica, are already harnessed by 9 (nine) Hydroelectric power plants with large dams, four on Neretva main stream, one with a major dam on the Rama tributary, and another four on the Trebišnjica River (one of these being in Croatia).[2]

These facilities are as follows:

- on the Neretva: Jablanica Hydroelectric Power Station, Grabovica Hydroelectric Power Station, Salakovac Hydroelectric Power Station, Mostar Hydroelectric Power Station;

- on the Rama: Rama Hydroelectric Power Station;

- on the Trebišnjica: Trebinje-1 Hydroelectric Power Station, Trebinje-2 Hydroelectric Power Station, Čapljina Hydroelectric Power Station, Dubrovnik Hydroelectric Power Station (in Croatia).

There are additionally a number of hydroelectric power station of various capacities on smaller tributaries, such as Mostarsko Blato Hydroelectric Power Station on the Lištica (downstream from HPP named Jasenica), Peć Mlini Hydroelectric Power Station on the Trebižat, and numerous small hydro projects on the small river tributaries like Tatinac, Trešanica, Neretvica and Duščica, with a proposed small hydro on the rivers Doljanka, Glogošnica, and one abandoned on the Idbar.

Projects in Upper Neretva

The government of the Bosnia and Herzegovina has unveiled plans to build three more hydroelectric power plants with dams over 150.5 metres in height[2] upstream from the existing plants, beginning with Glavaticevo Hydro Power Plant in the village of Glavatičevo, then going upstream to Bjelimići Hydro Power Plant and Ljubuča Hydro Power Plant located near the eponymous villages; and another, by the Republic of Srpska, at the Neretva headwaters gorge, near the source of the river. It is similarly opposed by environmental organizations and NGO's, such as Zeleni-Neretva Konjic[41] and the World Wildlife Fund.[5][19][42][43][44]

Meanwhile, Bosnia and Herzegovina entity, Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, was preparing a parallel plan to form a large, protected area as a national park which would include the entire region of Gornja Neretva (English: Upper Neretva), and have within the park the three hydroelectric plants. The latest idea is that the park should be divided in two, where the Neretva should be excluded from both and would become the boundary between parks. Those who oppose the plan wish to have the area turned into the National Park of Upper Neretva and would leave the park without substantial development.[40][45][46]

Projects in Ulog

Since the 2000's, the other entity of Bosnia, Republica Srpska, has developed plans to construct up to eight Hydroelectric power plants, seven small hydroelectric power plants, and one large, namely HE Ulog, on the stretch of the Neretva with high ecological value, which lies within the entity's administrative lines.[47] This stretch consists of around 40 kilometers of the course of the Neretva between its source and the entity boundary at Ljusići village. Opposition to these plans, and ongoing construction of HE Ulog in particular, attracted both domestic and international experts, activists and public, who voiced their opposition with scientific arguments, even taking the issue to European Council.[48] Irregularities in planning and design, the flawed environmental impact study and the complete absence of research work on the ground related to the geological instability of the terrain, as well as irregularities in the implementation of tenders and the issuance of environmental and construction permits, are particularly noteworthy. In the environmental impact study, the only significant impact, one that should be reflected on the downstream part of the Neretva watercourse, is completely ignored. Such drastic disregard in planning and designing, considering that the facilities of HE Ulog are located on the very line of demarcation of two ethnically based entities, which makes the downstream of the river located entirely in another administrative entity, where all the ecological consequences resulting from the use of Neretva water and the production of electricity will be felt exclusively, introduces, besides environmental, also an ethnic and political dimension to the issue.[49][50]

The Upper Horizons - Trebišnjica

In recent times the Republic of Srpska government finished the project named The Upper Horizons (Bosnian: Gornji horizonti), a large hydroelectric project that diverted underground waters in the Neretva watershed to the Trebišnjica plant and others in the Trebišnjica basin. This project was opposed by NGO's in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia. They argued that the project would increase salinity levels of every surface and underground water on the right bank of the Neretva, damage internationally recognized Ramsar sites, a protected Nature Park Hutovo Blato in Bosnia and Herzegovina, protected Neretva Delta in Croatia, and important reservoirs of freshwater, plus agricultural lands in the lower Neretva valley.[51][52][53][54]

Cultural and historical significance

Early history

During antiquity, the Neretva was known as Narenta, Narona and Naro(n),[55][56][57] and was the inland[58] home to the ancient Illyrian tribe of Ardiaei. They became ship builders, seafarers and fishermen. Archaeological discoveries of Illyrian culture dealt both with daily and religious life such as the discovery of ancient Illyrian shipwrecks found in Hutovo Blato, in the vicinity of the Neretva River.[59]

After intense excavations in the area of Hutovo Blato in the autumn of 2008, archaeologists from Bosnia and Herzegovina University of Mostar and Sweden University of Lund found traces of an Illyrian trading post that was more than two thousand years old. The find is unique in a European perspective and archaeologists have concluded that Desilo, as the location is called, was an important trading post of great significance for contact between the Illyrians and the Romans. Archaeological finds include the ruins of a settlement, the remains of a harbour that probably functioned as a trading post, as well as many sunken boats, fully laden with wine pitchers – so-called amphorae – from the 1st century BC.[60] Archaeologist Adam Lindhagen claimed that it was the most important Illyrian ruin.[61][62]

Roman period

One of the most significant monuments of Roman times in Bosnia and Herzegovina is Mogorjelo. Located 1 kilometer south of the town of Čapljina, Mogorjelo remnants of the old Roman suburban Villa Rustica from the 4th century represents ancient Roman agricultural production and estate, mills, bakeries, olive oil refinery and forges.[63] The Villa was destroyed in the middle of the 4th century, during the invasion of western Goths. Surviving residents did not restore it to its original splendor. The name of Mogorjelo is thought to be derived either from the Slavic word for "burn" (Slavic – goriti) or that at the end of the 5th century the church was built on the ruins of the Villa, and was dedicated to St. Hermagor – Mogoru.[64]

Middle Ages

In the Early Middle Ages, the South Slavic Narentines held the region. They were known for piracy and resisted Christianization until they were defeated by the Venetians, and then the Byzantines, at the turn of the 10th and 11th centuries.

Gabela is a rich archaeological site on the Neretva bank, situated 5 km (3 miles) south of Čapljina. Along with notable medieval buildings, remains of Old City walls, and a sculpture of a stone lion – a symbol of Venetian culture survived.

Ottoman period

The Old Bridge was commissioned by Suleiman the Magnificent in 1557 to replace an older wooden suspension bridge. Construction began in 1557 and took nine years: according to the inscription the bridge was completed in 974 AH, corresponding to the period between 19 July 1566 and 7 July 1567. Memories and legends and the name of the builder, Mimar Hayruddin (student of the Old/Great Sinan (Mimar Sinan / Koca Sinan), the Ottoman architect) were preserved in writing. Charged under pain of death to construct a bridge of such unprecedented dimensions, the architect reportedly prepared for his own funeral on the day the scaffolding was finally removed from the completed structure. Upon its completion it was the widest man-made arch in the world. Associated technical issues remain obscure: how the scaffolding was erected, how the stone was transported from one bank to the other, and how the scaffolding was maintained during construction. On 9 November 1993, during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina it was destroyed by sustained artillery shelling.[65] After the war, immediate plans were raised to reconstruct the bridge as a symbol of peace and ethnic harmony, literally bridging the two sides of the conflict. They attempted to reuse as much original material as possible. Salvage operations, funded by the international community, raised the stones and the remains of the bridge from the river bed. Missing elements or parts that were not usable were cut from the original quarry. Now listed as a World Heritage Site, the bridge was rebuilt under the aegis of UNESCO. Its 1,088 stones were shaped according to the original techniques, at a cost of about €12 million. The grand opening was held on 23 July 2004.

It is traditional for the town's young men to leap from the 24 metres (79 ft) bridge into the Neretva. The practice dates back to 1566, the time the bridge was built, and an event was held every summer in front of the populace. The first recorded instance of someone diving off the bridge is from 1664. In 1968 a formal diving competition was inaugurated and held every summer.[66]

Počitelj is situated on a hill near Mostar and is easily accessible by bus. As with many other Bosnian sites, this town is Ottoman in design. It is a historic fortified town with a hostel (caravanserai) and a hamam beneath. A traditional mosque is there. During the Bosnian War Počitelj was badly damaged and most of its residents fled and never returned[67]

World War II: Battle of the Neretva

The famous Battle of Neretva is a 1969 Oscar-nominated motion picture depicting events from the Second World War and the actual Battle of the Neretva.[68] Codenamed Fall Weiß, the operation was a German plan for a combined attack launched in early 1943 against Yugoslav Partisans throughout occupied Yugoslavia. The offensive took place between January and April 1943. The operation used to be known, in socialist Yugoslav times, as the Fourth Enemy Offensive, or as the Battle for the Wounded.

At one point during the battle, the Partisans were caught in a pocket with their back to the Neretva River. Near Jablanica, 20,000 Partisans under command of Marshal Josip Broz Tito struggled to save some 4500 wounded comrades and typhus patients together with the Supreme Headquarters and Main Hospital, against some 150,000 Axis combatants.[69]

In popular culture

Celebrated Bosnian and Herzegovinian poet, Mak Dizdar often used the river Neretva as motif in his poetry, alongside other historical, cultural and natural feature of his native Herzegovina. The famous Battle of Neretva is a 1969 Oscar-nominated motion picture depicting events from the World War II and the actual Battle of the Neretva.[68] Many folk songs are written or performed with the Neretva as main theme.

Gallery

View from the Old Bridge in Mostar

View from the Old Bridge in Mostar Neretva River in seen from Musala Bridge in Mostar

Neretva River in seen from Musala Bridge in Mostar The mouth of the Neretva river and Adriatic sea

The mouth of the Neretva river and Adriatic sea

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Croatia 2017 (PDF) (in Croatian and English). Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2017. p. 47. ISSN 1333-3305. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Methodology and Technical Notes". IUCN - Watersheds of the World. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

A large dam is defined by the industry as one higher than 15 metres high and a major dam as higher than 150.5 metres

- 1 2 "Transboundary management of the lower Neretva valley". Ramsar Convention. 14 March 2002. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "UNDP H2O Knowledge Fair - Bosnia and Herzegovina". UNDP H2O Knowledge Fair. Archived from the original on 21 November 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

There are about 30 water reservoirs in Bosnia and Herzegovina primarily on the Neretva and Trebisnjica basin, ...

- 1 2 3 "Living Neretva". WWF - World Wide Fund. Archived from the original on 3 February 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ↑ "Geoheritage of the Balkan Peninsula" (PDF). The Geological Survey of Sweden (SGU). Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ↑ "Database of researchers and research institutions in BiH - Project of identification and characterisation of autochthonous human, animal and plant resource of the Neretva - Resume". Database of researchers and research institutions in B&H. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ↑ "Metkovi?". Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ↑ "Neretva River Sub-basin". Internationally Shared Surface Water Bodies in the Balkan Region. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- ↑ "Daily hydrological report". State Hydrometeorological Bureau of the Republic of Croatia. Archived from the original on 30 May 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- 1 2 "Hydrological characteristics of Bosnia and Herzegovina - Adriatic watershed". Hydro-meteorological institute of Federation of B&H. Archived from the original on 23 March 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- 1 2 3 "HE Jablanica - Elektroprivreda BiH". www.elektroprivreda.ba. JP Elektroprivreda BiH. Archived from the original on 23 November 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ "EuroNatur: Neretva-Delta". www.euronatur.org. EuroNatur. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ "Water Quality Protection Project - Environmental Assessment". World Bank. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ↑ "BHTourism - Rakitnica". Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ↑ Hutovo Blato Nature Park Archived 18 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 "Hutovo Blato Nature Park". Network of Adriatic Parks. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Water power: the upper Neretva River, Bosnia-Herzegovina". WWF - World Wide Fund. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- 1 2 "Nature in Neretva Delta". Neretva.info - Neretva Delta. Archived from the original on 1 August 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- ↑ Smith, Kevin G.; Darwall, William R. T. (2006). The Status and Distribution of Freshwater Fish Endemic to the Mediterranean Basin. IUCN. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-2-8317-0908-6. Archived from the original on 9 November 2023. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- 1 2 Skaramuca Boško; Dulčić Jakov (14 December 2007). Endangered and endemic species of fish in the basins of the Neretva river, Trebišnjica and Morača. Dubrovnik: Sveučilište u Dubrovniku; EastWest Institute. pp. 43–46. ISBN 978-953-7153-18-2.

- ↑ "Sander lucioperca". Fishbase. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ↑ "Marble trout (Salmo marmoratus)". Balkan Trout Restoration Group. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ↑ S. MUHAMEDAGIĆ; H. M. GJOEN; M. VEGRA (2008). "Salmonids of the Neretva river basin - p" (PDF). EIFAC FAO Fisheries and Aqauculture Report No. 871. European Inland Fisheries Advisory Commission (EIFAC): 224–233. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ↑ "Salmo obtusirostris". Balkan Trout Restoration Group. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ↑ "Salmo dentex". Balkan Trout Restoration Group. Archived from the original on 22 June 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ↑ "Salmo marmoratus". Balkan Trout Restoration Group. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ↑ Freyhof, J.; Kottelat, M. (2008). "Salmo dentex". 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- ↑ Crivelli, A.J. (2006). "Salmo marmoratus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2006: e.T19859A9043279. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2006.RLTS.T19859A9043279.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ "Adriatic minnow (Phoxinellus alepidotus)". Fishbase. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ↑ "Spotted minnow (Phoxinellus adspersus)". Fishbase. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ↑ "Neretvan Nase (Chondrostoma knerii)". Fishbase. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ↑ Crivelli, A.J. (2006). "Chondrostoma knerii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2006: e.T4788A11094572. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2006.RLTS.T4788A11094572.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ "(Squalius svallize also Leuciscus svallize)". Fishbase. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ↑ "Ilirski klijen (Squalius illyricus)". Fishbase. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ↑ "Turkish chub (Leuciscus turskyi)". Fishbase. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ↑ "Dalmatian Barbelgudgeon (Aulopyge hugeli)". Fishbase. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- 1 2 Mrakovcic, Milorad & Brigić, Andreja & Buj, Ivana & Ćaleta, Marko & Mustafić, Perica & Zanella, Davor. (2006). Red Book of Freshwater Fish in Croatia

- 1 2 "Our view of the Hydroelectrical Power Station System "Upper Neretva"" (PDF). Konjic NGO For Preservation of the Neretva River And Environment Protection. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2008. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ↑ "ZELENI-NERETVA Konjic NGO For Preservation of the Neretva River And Environment Protection". Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ↑ "Fondacija Heinrich Böll". Archived from the original on 22 May 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ↑ "REC - The Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe". Archived from the original on 13 September 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ↑ "Declaration for the Protection of the Neretva River". NGO For Preservation of the Neretva River And Environment Protection. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ↑ Silenced Rivers: The Ecology and Politics of Large Dams, by Patrick McCully, Zed Books, London, 1996

- ↑ "Arguments Pro&Contra - Why Are We Contra The Hydroelectrical Power Station System "Upper Neretva"". ZELENI-NERETVA Konjic NGO For Preservation of the Neretva River And Environment Protection. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ↑ "Problematična HE Ulog na Neretvi izazvala niz protesta" [=The problematic HPP Ulog on the Neretva caused a series of protests]. energetika-net.com (in Serbo-Croatian). Banja Luka: Energetika-Net. 28 October 2020. Archived from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ↑ Meliha Kešmer (26 October 2020). "Rijeku Neretvu od bh. vlasti i investitora brane i pred Vijećem Europe" [The Neretva River is being defended from the Bosnian authorities and investors even before the Council of Europe]. Radio Slobodna Evropa (in Serbo-Croatian). Archived from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ↑ "O projektu HE ULOG na gornjoj Neretvi" [About the HE ULOG project on the upper Neretva]. Zeleni Neretva (in Bosnian). 27 April 2022. Archived from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ↑ "Decenija bitke za Neretvu: HE Ulog – katastrofa u realizaciji" [A decade of the battle for Neretva: HPP Ulog – a disaster in the making]. AbrašMEDIA (in Serbo-Croatian). 30 October 2021. Archived from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ↑ Mirsad Behram (2 February 2014). ""Gornji horizonti" već nanijeli štetu" [The "Upper Horizons" have already done damage]. Radio Slobodna Evropa (in Serbo-Croatian). Archived from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ↑ Ruža Tomašić (6 March 2014). "Parliamentary question | Impact of the Upper Horizons project on the ecosystem of the river Neretva and the local economy". www.europarl.europa.eu. European Parliament. Archived from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ↑ "Slobodna Dalmacija - Uzbuna u dolini Neretve; 'krade' se voda iz rijeke zbog nove hidroelektrane koju gradi Republika Srpska u suradnji s Kinezima: 'Uništit će nas!'" [Alarm in the Neretva Valley; water is being 'stolen' from the river because of the new hydroelectric power plant that Republika Srpska is building in cooperation with the Chinese: 'It will destroy us!']. slobodnadalmacija.hr (in Croatian). 10 January 2022. Archived from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ↑ "DOZNAJEMO Zbog projekta Gornji horizonti Hrvatska prijavljuje BIH europskim institucijama" [Because of the Gornji Horizonti project, Croatia reports BIH to European institutions]. Morski HR (in Croatian). 18 January 2022. Archived from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ↑ Archeological Museum of Narona

- ↑ The Ancient City of Narona Archived 22 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Neven Kazazovic, Tajne Neretve

- ↑ Appian and Illyricum by Marjeta Šašel Kos Archived 24 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine," The Ardiaei were certainly also settled in the hinterland, along the Naro River at least as far as the Konjic region,"

- ↑ Illyria Archived 4 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Bosnian archaeologists discover fabled ships". iol.co.za. Archived from the original on 2 November 2005. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ↑ "The world's first Illyrian trading post found". Apollon - University of Oslo. Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ↑ "Unique Archaeological Discovery in Balkan: World's First Illyrian Trading Post Found". Science Daily. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ↑ "Mogorjelo on the Vine route of Herzegovina". Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ↑ Čapljina municipality - Mogorjelo Archived 11 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "ICTY: Prlić et al. (IT-04-74)". Archived from the original on 2 August 2009.

- ↑ Diving Club Mostar Archived 12 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ World Heritage Sites in Bosnia Herzegovina Archived 23 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Neretva at IMDb

- ↑ "Operation WEISS – The Battle of Neretva". Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2009.