Bunraku (文楽) (also known as Ningyō jōruri (人形浄瑠璃)) is a form of traditional Japanese puppet theatre, founded in Osaka in the beginning of the 17th century, which is still performed in the modern day.[1] Three kinds of performers take part in a bunraku performance: the Ningyōtsukai or Ningyōzukai (puppeteers), the tayū (chanters), and shamisen musicians. Occasionally other instruments such as taiko drums will be used. The combination of chanting and shamisen playing is called jōruri and the Japanese word for puppet (or dolls, generally) is ningyō. It is used in many plays.

History

Bunraku's history goes as far back as the 16th century, but the origins of its modern form can be traced to around the 1680s. It rose to popularity after the playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1724) began a collaboration with the chanter Takemoto Gidayu (1651–1714), who established the Takemoto puppet theater in Osaka in 1684.

Originally, the term bunraku referred only to the particular theater established in 1805 in Osaka, which was named the Bunrakuza after the puppeteering ensemble of Uemura Bunrakuken (植村文楽軒, 1751–1810), an early 18th-century puppeteer from Awaji, whose efforts revived the flagging fortunes of the traditional puppet theatre.

Elements of the form

The puppets of the Osaka tradition tend to be somewhat smaller overall, while the puppets in the Awaji tradition are some of the largest as productions in that region tend to be held outdoors.

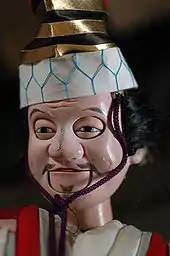

The heads and hands of traditional puppets are carved by specialists, while the bodies and costumes are often constructed by puppeteers. The heads can be quite mechanically sophisticated; in plays with supernatural themes, a puppet may be constructed so that its face can quickly transform into that of a demon. Less complex heads may have eyes that move up and down, side to side or close, and noses, mouths, and eyebrows that move.

Controls for all movements of parts of the head are located on a handle that extends down from the neck of the puppet, and are reached by the main puppeteer inserting their left hand into the chest of the puppet through a hole in the back of the torso.

The main puppeteer, the omozukai, uses their right hand to control the right hand of the puppet, and uses their left hand to control the puppet's head. The left puppeteer, known as the hidarizukai or sashizukai, depending on the tradition of the troupe, manipulates the left hand of the puppet with their own right hand by means of a control rod that extends back from the elbow of the puppet. A third puppeteer, the ashizukai, operates the feet and legs. Puppeteers begin their training by operating the feet, then move on to the left hand, before being able to train as the main puppeteer. Many practitioners in the traditional puppetry world, particularly those in the National Theater, describe the long training period, which often requires ten years on the feet, ten years on the left hand, and ten years on the head of secondary characters before finally developing the requisite skills to move to the manipulation of the head of a main character, as an artistic necessity. However, in a culture like that of Japan, which privileges seniority, the system can also be considered a mechanism to manage competition among artistic egos and provide for a balance among the demographics of the puppeteers in a troupe in order to fill each role.

All but the most minor characters require three puppeteers, who perform in full view of the audience, generally wearing black robes. In most traditions, all puppeteers also wear black hoods over their heads, but a few others, including the National Bunraku Theater, leave the main puppeteer unhooded, a style of performance known as dezukai. The shape of the puppeteers' hoods also varies, depending on the school to which the puppeteer belongs.

Usually a single chanter recites all the characters' parts, altering his vocal pitch and style in order to portray the various characters in a scene. Occasionally multiple chanters are used. The chanters sit next to the shamisen player. Some traditional puppet theaters have a revolving platform for the chanter and shamisen player, which rotates to bring replacement musicians in for the next scene.

The shamisen used in bunraku is slightly larger than other kinds of shamisen and has a different sound, lower in pitch and with a fuller tone.

Bunraku shares many themes with kabuki. In fact, many plays were adapted for performance both by actors in kabuki and by puppet troupes in bunraku. Bunraku is particularly noted for lovers' suicide plays. The story of the forty-seven rōnin is also famous in both bunraku and kabuki.

Bunraku is an author's theater, as opposed to kabuki, which is a performer's theater. In bunraku, prior to the performance, the chanter holds up the text and bows before it, promising to follow it faithfully. In kabuki, actors insert puns on their names, ad-libs, references to contemporary happenings and other things which deviate from the script.

The most famous bunraku playwright was Chikamatsu Monzaemon. With more than 100 plays to his credit, he is sometimes called the Shakespeare of Japan.

Bunraku companies, performers, and puppet makers have been designated "Living National Treasures" under Japan's program for preserving its culture.

Today

Osaka is the home of the government-supported troupe at National Bunraku Theatre. The theater offers five or more shows every year, each running for two to three weeks in Osaka before moving to Tokyo for a run at the National Theater. The National Bunraku Theatre also tours within Japan and occasionally abroad.

Until the late 1800s there were also hundreds of other professional, semi-professional, and amateur troupes across Japan that performed traditional puppet drama.

Since the end of World War II, the number of troupes has dropped to fewer than 40, most of which perform only once or twice a year, often in conjunction with local festivals. A few regional troupes, however, continue to perform actively.

The Awaji Puppet Troupe, located on Awaji Island southwest of Kobe, offers short daily performances and more extensive shows at its own theater and has toured the United States, Russia and elsewhere abroad.

The Tonda Puppet Troupe (冨田人形共遊団) of Shiga Prefecture, founded in the 1830s, has toured the United States and Australia on five occasions and has been active in hosting academic programs in Japan for American university students who wish to train in traditional Japanese puppetry.

The Imada Puppet Troupe, which has performed in France, Taiwan, and the United States, as well as the Kuroda Puppet Troupe are located in the city of Iida, in Nagano Prefecture. Both troupes, which trace their histories back more than 300 years, perform frequently and are also active in nurturing a new generation of traditional puppeteers and expanding knowledge of puppetry through training programs at local middle schools and by teaching American university students in summer academic programs at their home theaters.

The increase in interest in bunraku puppetry has contributed to the establishment of the first traditional Japanese puppet troupe in North America. Since 2003, the Bunraku Bay Puppet Troupe, based at the University of Missouri in Columbia, Missouri, has performed at venues around the United States, including the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and the Smithsonian Institution, as well as in Japan. They have also performed alongside the Imada Puppet Troupe.[2] The Center for Puppetry Arts in Atlanta, Georgia, has an extensive variety of bunraku puppets in its Asian collection.[3]

Music and song

The chanter/singer (tayū) and the shamisen player provide the essential music of the traditional Japanese puppet theater. In most performances only a shamisen player and a chanter perform the music for an act. Harmony between these two musicians determines the quality of their contribution to the performance.[4]

The role of the tayū is to express the emotions and the personality of the puppets. The tayū performs not only the voice of each of the characters, but also serves as the narrator of the play.

Located to the side of the stage the tayū physically demonstrates facial expressions of each character while performing their respective voices. While performing multiple characters simultaneously the tayū facilitates the distinction between characters by exaggerating their emotions and voices. This is also done to maximize the emotional aspects for the audience.

In bunraku the futo-zao shamisen which is the largest shamisen as well as that of the lowest register, is employed.

The instruments most frequently used are flutes, in particular the shakuhachi, the koto and various percussion instruments.

Puppets

The head

The heads of the puppets (kashira) are divided into categories according to gender, social class and personality. Certain heads are created for specific roles, others can be employed for several different performances by changing the clothing and the paint. The heads are in effect repainted and prepared before each presentation.[5][6]

There are approximately 80 types of puppet heads broadly classified, and the Digital Library of the Japan Arts Council (ja) lists 129 types of puppet heads.[7][8]

Some of these heads have special tricks on them, and by pulling the strings of these tricks, the expression of the puppet can be changed to show that the human has turned into a yōkai (strange apparition) or a onryō (vengeful spirit) by activating the trick. For example, by pulling a string, the gabu, a type of head, can instantly split a beautiful woman's mouth open up to her ears and grow fangs, her eyes change to a large golden color and she grows golden horns. It is possible to represent the transformation of a woman into hannya (female demon) in a single head. The head of Tamamo-no-Mae, by pulling a string, can instantly cover the face of a beautiful woman with a kitsune (fox) mask. It is possible to represent, with a single head, the true appearance of the nine-tailed fox that was disguised as Tamamo-no-Mae.[7][9] Note that in Noh, the change in the attributes of the characters is represented by removing one of the double-layered Noh masks.[10] The nashiwari, a type of head, can be made by pulling a string to split the head in two, revealing a red section to represent a head severed by a sword.[7]

The preparation of the hair constitutes an art in and of itself. The hair distinguishes the character and can also indicate certain personality traits. The hair is made from human hair, however yak tail can be added to create volume. The ensemble is then fixed on a copper plate. To ensure that the puppet head is not damaged, the finishing of the hairstyle is made with water and beeswax, not oil.[11]

Costumes

The costumes are designed by a costume master and are composed of a series of garments with varying colors and patterns. These garments typically include a sash and a collar as well as an underkimono (juban), a kimono, and a haori or an outer robe (uchikake). In order to keep the costumes soft they are lined with cotton.[12]

As the clothing of the puppets wear out or are soiled the clothing is replaced by the puppeteers. The process of dressing or redressing the puppets by the puppeteers is called koshirae.

Construction

A puppet's skeletal structure is simple. The carved wooden kashira is attached to the head grip, or dogushi, and thrust down an opening out of the puppet's shoulder. Long material is draped over the front and back of the shoulder board, followed by the attachment of cloth. Carved bamboo is attached to create the hips of the puppet, arms and legs are tied to the body with lengths of rope. There is no torso to the puppet, as it would merely block out the puppeteer's range of movement of the individual limbs. The isho, or costume of the doll is then sewn on to cover over any cloth, wooden or bamboo parts that the artist does not wish to be seen. Finally, a slit is created in the back of the costume in order for the chief puppeteer to firmly handle the dogushi head stick.[13]

Text and the puppets

Unlike kabuki, which emphasizes the performance of the main actors, bunraku simultaneously demonstrates elements of presentation (directly attempting to invoke a certain response) and representation (trying to express the ideas or the feelings of the author). In this way attention is given to both visual and musical aspects of the puppets as well as the performance and the text. Every play begins with a short ritual in which the tayū, kneeling behind a small but ornate lectern, reverentially lifts their copy of the script to demonstrate devotion to a faithful rendering of the text. The script is presented at the beginning of each act as well.

Performers

Despite their complex training the puppeteers originated from a very destitute background. The kugutsu-mawashi were itinerants and as a result were treated as outcasts by the educated, richer class of Japanese society at the time. As a form of entertainment, the men would operate small hand puppets and put on miniature theatre performances, while women were often skilled in dancing and magic tricks which they used to tempt travelers to spend the night with them. The whole environment that gave birth to these puppet shows is reflected in the themes.[14]

Stage

The musician's stage (yuka)

The yuka is the auxiliary stage upon which the gidayu-bushi is performed. It juts out into the audience area at the front right area of the seats. Upon this auxiliary stage there is a special rotating platform. It is here that the chanter and the shamisen player make their appearance, and, when they are finished, it turns once more, bringing them backstage and placing the next performers on the stage.[15]

The partitions (tesuri) and the pit (funazoko)

In the area between upstage and downstage, there are three stage positions, known as "railings" (tesuri). Located in the area behind the second partition is often called the pit and it is where the puppeteers stand in order to carry out the puppets' lifelike movements.

Small curtain (komaku) and screened-off rooms (misuuchi)

This stage looks from an angle of the audience, the right side is referred to as the kamite (stage left), while the left side is referred to as the shimote (stage right). The puppets are made to appear and then leave the stage through the small black curtains. The blinded screens are just above these small curtains, and they have special blinds made from bamboo so that the audience cannot see inside.

Large curtain (joshiki-maku)

The joshiki-maku is a large, low hanging curtain hanging off of a ledge called the san-n-tesuri. It is used to separate the area where the audience is sitting from the main stage. The puppeteers stood behind the joshiki-maku, holding their puppets above the curtain while being hidden from the audience. However, the dezukai practice established later in the bunraku form would let the actors be seen on stage moving with the puppets, nulling the use of the curtains.[16]

See also

- Hachioji Kuruma Ningyo

- Shigeru Nanba, Japanese painter who features bunraku puppets in his works

References

- ↑ "The History of Bunraku 1". The Puppet Theater of Japan: Bunraku. An Introduction to Bunraku: A Guide to Watching Japan's Puppet Theater. Japan Arts Council. 2004. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ↑ "Bunraku Bay performs with 300-year-old troupe". themaneater.com. Archived from the original on 1 August 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ↑ Asian Collection at the Center for Puppetry Arts

- ↑ An Introduction to Bunraku, Japan Arts Council, The Chanter and the Shamisen Player Archived 31 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ An Introduction to Bunraku, Japan Arts Council, The Puppet's Head Archived 21 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ An Introduction to Bunraku, Japan Arts Council, Making the Puppet's Head Archived 16 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 かしらの種類 (in Japanese). Japan Arts Council. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ↑ 首(かしら)で探す (in Japanese). Japan Arts Council. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ↑ "Bunraku Dolls: Types of Heads". Japan Arts Council. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ↑ Seki Kobayashi, Tetsuo Nishi, and Hisashi Hata (2012). 能楽大事典. Chikuma Shobō. p. 200, 307, 741. ISBN 978-4480873576.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ An Introduction to Bunraku, Japan Arts Council, The Puppet's Wig Archived 22 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ An Introduction to Bunraku, Japan Arts Council, The Puppet's Costumes Archived 3 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Adachi, Barbara (1978). The Voice and Hands of Bunraku. Tokyo: Mobil Seikyu Kabushiki Kaisha.

- ↑ Ortolani, Benito (1995). The Japanese Theatre: From Shamanistic Ritual to Contemporary Pluralism. Princeton University: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04333-7.

- ↑ Brazell, Karen (1998) [1997]. Traditional Japanese Theater. Columbia University Press. pp. 115–124. ISBN 0-231-10872-9.

- ↑ Leiter, Samuel (2006). Historical Dictionary of Japanese Traditional Theatre. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press.