In theoretical computer science, a nondeterministic Turing machine (NTM) is a theoretical model of computation whose governing rules specify more than one possible action when in some given situations. That is, an NTM's next state is not completely determined by its action and the current symbol it sees, unlike a deterministic Turing machine.

NTMs are sometimes used in thought experiments to examine the abilities and limits of computers. One of the most important open problems in theoretical computer science is the P versus NP problem, which (among other equivalent formulations) concerns the question of how difficult it is to simulate nondeterministic computation with a deterministic computer.

Background

In essence, a Turing machine is imagined to be a simple computer that reads and writes symbols one at a time on an endless tape by strictly following a set of rules. It determines what action it should perform next according to its internal state and what symbol it currently sees. An example of one of a Turing Machine's rules might thus be: "If you are in state 2 and you see an 'A', then change it to 'B', move left, and change to state 3."

Deterministic Turing machine

In a deterministic Turing machine (DTM), the set of rules prescribes at most one action to be performed for any given situation.

A deterministic Turing machine has a transition function that, for a given state and symbol under the tape head, specifies three things:

- the symbol to be written to the tape (it may be the same as the symbol currently in that position, or not even write at all, resulting in no practical change),

- the direction (left, right or neither) in which the head should move, and

- the subsequent state of the finite control.

For example, an X on the tape in state 3 might make the DTM write a Y on the tape, move the head one position to the right, and switch to state 5.

Intuition

In contrast to a deterministic Turing machine, in a nondeterministic Turing machine (NTM) the set of rules may prescribe more than one action to be performed for any given situation. For example, an X on the tape in state 3 might allow the NTM to:

- Write a Y, move right, and switch to state 5

or

- Write an X, move left, and stay in state 3.

Resolution of multiple rules

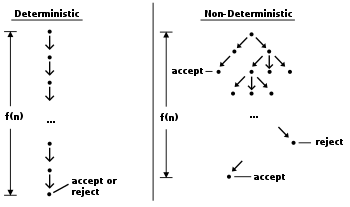

How does the NTM "know" which of these actions it should take? There are two ways of looking at it. One is to say that the machine is the "luckiest possible guesser"; it always picks a transition that eventually leads to an accepting state, if there is such a transition. The other is to imagine that the machine "branches" into many copies, each of which follows one of the possible transitions. Whereas a DTM has a single "computation path" that it follows, an NTM has a "computation tree". If at least one branch of the tree halts with an "accept" condition, the NTM accepts the input.

Definition

A nondeterministic Turing machine can be formally defined as a six-tuple , where

- is a finite set of states

- is a finite set of symbols (the tape alphabet)

- is the initial state

- is the blank symbol

- is the set of accepting (final) states

- is a relation on states and symbols called the transition relation. is the movement to the left, is no movement, and is the movement to the right.

The difference with a standard (deterministic) Turing machine is that, for deterministic Turing machines, the transition relation is a function rather than just a relation.

Configurations and the yields relation on configurations, which describes the possible actions of the Turing machine given any possible contents of the tape, are as for standard Turing machines, except that the yields relation is no longer single-valued. (If the machine is deterministic, the possible computations are all prefixes of a single, possibly infinite, path.)

The input for an NTM is provided in the same manner as for a deterministic Turing machine: the machine is started in the configuration in which the tape head is on the first character of the string (if any), and the tape is all blank otherwise.

An NTM accepts an input string if and only if at least one of the possible computational paths starting from that string puts the machine into an accepting state. When simulating the many branching paths of an NTM on a deterministic machine, we can stop the entire simulation as soon as any branch reaches an accepting state.

Alternative definitions

As a mathematical construction used primarily in proofs, there are a variety of minor variations on the definition of an NTM, but these variations all accept equivalent languages.

The head movement in the output of the transition relation is often encoded numerically instead of using letters to represent moving the head Left (-1), Stationary (0), and Right (+1); giving a transition function output of . It is common to omit the stationary (0) output,[1] and instead insert the transitive closure of any desired stationary transitions.

Some authors add an explicit reject state,[2] which causes the NTM to halt without accepting. This definition still retains the asymmetry that any nondeterministic branch can accept, but every branch must reject for the string to be rejected.

Computational equivalence with DTMs

Any computational problem that can be solved by a DTM can also be solved by a NTM, and vice versa. However, it is believed that in general the time complexity may not be the same.

DTM as a special case of NTM

NTMs include DTMs as special cases, so every computation that can be carried out by a DTM can also be carried out by the equivalent NTM.

DTM simulation of NTM

It might seem that NTMs are more powerful than DTMs, since they can allow trees of possible computations arising from the same initial configuration, accepting a string if any one branch in the tree accepts it. However, it is possible to simulate NTMs with DTMs, and in fact this can be done in more than one way.

Multiplicity of configuration states

One approach is to use a DTM of which the configurations represent multiple configurations of the NTM, and the DTM's operation consists of visiting each of them in turn, executing a single step at each visit, and spawning new configurations whenever the transition relation defines multiple continuations.

Multiplicity of tapes

Another construction simulates NTMs with 3-tape DTMs, of which the first tape always holds the original input string, the second is used to simulate a particular computation of the NTM, and the third encodes a path in the NTM's computation tree.[3] The 3-tape DTMs are easily simulated with a normal single-tape DTM.

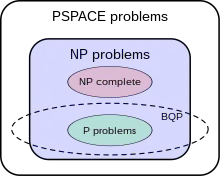

Time complexity and P versus NP

In the second construction, the constructed DTM effectively performs a breadth-first search of the NTM's computation tree, visiting all possible computations of the NTM in order of increasing length until it finds an accepting one. Therefore, the length of an accepting computation of the DTM is, in general, exponential in the length of the shortest accepting computation of the NTM. This is believed to be a general property of simulations of NTMs by DTMs. The P = NP problem, the most famous unresolved question in computer science, concerns one case of this issue: whether or not every problem solvable by a NTM in polynomial time is necessarily also solvable by a DTM in polynomial time.

Bounded nondeterminism

An NTM has the property of bounded nondeterminism. That is, if an NTM always halts on a given input tape T then it halts in a bounded number of steps, and therefore can only have a bounded number of possible configurations.

Comparison with quantum computers

Because quantum computers use quantum bits, which can be in superpositions of states, rather than conventional bits, there is sometimes a misconception that quantum computers are NTMs.[4] However, it is believed by experts (but has not been proven) that the power of quantum computers is, in fact, incomparable to that of NTMs; that is, problems likely exist that an NTM could efficiently solve that a quantum computer cannot and vice versa.[5] In particular, it is likely that NP-complete problems are solvable by NTMs but not by quantum computers in polynomial time.

Intuitively speaking, while a quantum computer can indeed be in a superposition state corresponding to all possible computational branches having been executed at the same time (similar to an NTM), the final measurement will collapse the quantum computer into a randomly selected branch. This branch then does not, in general, represent the sought-for solution, unlike the NTM, which is allowed to pick the right solution among the exponentially many branches.

See also

References

- ↑ Garey, Michael R.; David S. Johnson (1979). Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness. W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-1045-5.

- ↑ Erickson, Jeff. "Nondeterministic Turing Machines" (PDF). U. Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- ↑ Lewis, Harry R.; Papadimitriou, Christos (1981). "Section 4.6: Nondeterministic Turing machines". Elements of the Theory of Computation (1st ed.). Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. pp. 204–211. ISBN 978-0132624787.

- ↑ The Orion Quantum Computer Anti-Hype FAQ, Scott Aaronson.

- ↑ Tušarová, Tereza (2004). "Quantum complexity classes". arXiv:cs/0409051..

General

- Martin, John C. (1997). "Section 9.6: Nondeterministic Turing machines". Introduction to Languages and the Theory of Computation (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 277–281. ISBN 978-0073191461.

- Papadimitriou, Christos (1993). "Section 2.7: Nondeterministic machines". Computational Complexity (1st ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 45–50. ISBN 978-0201530827.