| North American cougar | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| A cougar at Wildlife Prairie Park in Illinois | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Felinae |

| Genus: | Puma |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | P. c. couguar[3] |

| Trinomial name | |

| Puma concolor couguar[3] (Kerr, 1792) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The North American cougar (Puma concolor couguar) is a cougar subspecies in North America. It is the biggest cat in North America (North American jaguars are fairly small).[4][5] It was once common in eastern North America and is still prevalent in the western half of the continent. This subspecies includes populations in western Canada, the western United States, Florida, Mexico and Central America, and possibly South America northwest of the Andes Mountains.[6] It thus includes the extirpated eastern cougar and extant Florida panther populations.

Taxonomic history

As of 2017, P. c. cougar was recognised as being valid by the Cat Classification Taskforce of the Cat Specialist Group. P. c. costaricensis had been regarded as a subspecies in Central America.[6][7]

Description

The North American cougar has a solid tan-colored coat without spots and weighs 25–80 kg (55–176 pounds).[8] Females average 50 kg (110 lb), about the same as a jaguar in the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve on the Mexican Pacific coast.[5]

Habitat and distribution

The North American cougar lives in various places and habitats.[8] Several populations still exist and are thriving in the western United States, Southern Florida, and western Canada, but the North American cougar was once commonly found in eastern portions of the United States. It was believed to be extirpated there in the early 1900s. In Michigan, it was thought to have been killed off and extinct in the early 1900s. Today there is evidence to support that cougars could be on the rise in Mexico and could have a substantial population in years to come. Some mainstream scientists believe that small relict populations may exist (around 50 individuals), especially in the Appalachian Mountains and eastern Canada.[9] Recent scientific findings in hair traps in Fundy National Park in New Brunswick have confirmed the existence of at least three cougars in New Brunswick.[9] The Ontario Puma Foundation estimates that there are currently 850 cougars in Ontario.

The Quebec wildlife services also considers cougars to be present in the province as a threatened species after multiple DNA tests confirmed cougar hair in lynx mating sites.[10] The only unequivocally known eastern population is the critically endangered Florida panther. There have been unconfirmed sightings in Elliotsville Plantation, Maine (north of Monson) and as early as 1997 in New Hampshire.[11]

Sightings in the United States

Reported sightings of cougars in the United States continue today, despite their status as extirpated.

- California

- Connecticut

- In 2011, a cougar was sighted in Greenwich, Connecticut, and later killed by an SUV in Milford after allegedly travelling 1,500 mi (2,400 km) from South Dakota.[14]

- Illinois

- On April 14, 2008, a cougar triggered a flurry of reports before being cornered and killed in the Chicago neighborhood of Roscoe Village while officers tried to contain it. The cougar was the first sighted in the city limits of Chicago since the city was founded in 1833.[15]

- On November 22, 2013, a cougar was found on a farm near Morrison in Whiteside County, Illinois. An Illinois Department of Natural Resources officer subsequently shot and killed the cougar after determining it posed a risk to the public.[16]

- Michigan

- According to the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, there were fifteen confirmed cougar sightings in the state in 2020 and, as of October, there had been ten confirmed sightings in the Upper Peninsula in 2021. The Department said that the steep increase in sightings may be attributable to the proliferation of trail cameras.[17]

- Tennessee

- On September 26, 2015, a hair sample was submitted by a hunter in Carroll County, Tennessee; DNA analysis indicated it was a female with genetics similar to cougars in South Dakota.[18] Bobcats in this state currently reside in regions that were once roamed by cougars.

- Wisconsin

- Genetic analysis of DNA from a cougar sighting in Wisconsin in 2008 indicated that a cougar was in Wisconsin and that it was not a captive animal. The cougar is thought to have migrated from a native population in the Black Hills of South Dakota; however, the genetic analysis could not affirm that hypothesis. Whether other, perhaps breeding, cougars are present is also uncertain. A second sighting was reported and tracks were documented in a nearby Wisconsin community. Unfortunately, a genetic analysis could not be done and a determination could not be made.[19] This cougar later made its way south into the northern Chicago suburb of Wilmette.

- On June 3, 2013, a verified sighting was made in Florence County, Wisconsin. The cougar was photographed by an automatic trail camera, and confirmed by DNR biologists in October, 2013.[20]

- In December, 2020, two sightings, one verified, were made in Dane County, in and around Stoughton, Wisconsin. The cougar was photographed by an individual, and confirmed by the Wisconsin DNR.

- In November 2021, a DNR representative told WDJT-TV that the Department confirms about 15 cougar sightings per year in the state.[21]

While the origins of these animals are unknown, some cougar experts believe some are captive animals that have been released or escaped.[22]

Ecology

The North American Cougar is a carnivore and its main sources of prey are deer, elk, mountain goats, moose and bighorn sheep. [23] Despite being a large predator, the North American Cougar can also be the prey of larger predators like wolves and bears.[24] The North American cougar usually hunts at night and sometimes travels long distances in search of food. They are short distance sprinters and can remain hidden for hours to surprise unsuspecting prey and pounce when they least expect it.[23] They use their strong jaws and large canines to puncture the neck of their prey, breaking the neck and efficiently killing their prey. They also grab their prey by the throat to suffocate it.[23] It is fast and can maneuver quite easily and skillfully.[7] Depending on the abundance of prey, such as deer, it shares the same prey as the jaguar in Central or North America.[25] Other sympatric predators include the grizzly bear and American black bears.[26] Cougars are known to prey on bear cubs.[27] Cougars in the Great Basin have been recorded to prey on feral horses,[28] as well as feral donkeys in the Sonoran and Mojave Deserts.[29]

Rivalry between the cougar and grizzly bear was a popular topic in North America. Fights between them were staged, and those in the wilderness were recorded by people, including native peoples.[30]

The North American Cougar plays an important role in regulating ecosystems as a large predator. The presence of the cougar as a predator prevents the overpopulation of herbivorous prey, like deer, in an ecosystem. Overpopulation of prey can result in the destruction of vegetation and biodiversity in an ecosystem.[23]

Reproduction

Adult male cougars can breed with multiple female cougars any time of the year, however the peak breeding season is in the months of January and August. When cougars are two years old, they reach the level of sexual maturity. The breeding process does not last a long time and after the male and female cougar mate, they separate. After mating, the male cougar plays no further role and the female cougar bears the full responsibility of raising its young. The average litter size is three cubs and each of the babies weigh a little over a pound. Cougars will breed until they occupy territory. Cougars have a 92 day gestation period allowing the breeding process to continue throughout the year.[23]

Threats and conservation

The primary causes of the declining population of cougars is due to hunting and loss of habitat. [24] Sport hunting and loss of territory reflect the most significant threats upon the cougar extinction status. Most of the cougars’ prey is found near humans. Whether it be through sport hunting or through the protection of livestock, humans kill cougars purposefully. Though there is evidence of indirect killings through vehicle collisions, the intentional human impact is drastic. Humans continue to affect the declining cougar population through the occupation of their habitats. Cougars tend to occupy areas that are prime for development and expansion. From mountains to deserts, humans utilize the cougar territory to build new sites and structures for human enjoyment.[31] As a consequence to the construction, cougars lose their habitats.

Even though conservation efforts of the cougar have decreased against the "more appealing" jaguar, it is hunted less frequently because it has no spots, and is thus less desirable to hunters.[7]

Despite the declining population of cougars, the extinction of the North American Cougar is not seen as a large concern.[24] In Oregon, a healthy population of 5,000 was reported in 2006, exceeding a target of 3,000.[32] California has actively sought to protect the cat and has an estimated population of 4,000 to 6,000.[33] With the increase of human development and infrastructure growth in California, the cougar populations in the state are becoming more isolated from one another.[34]

A 2012 study using 18 motion-sensitive cameras in Río Los Cipreses National Reserve counted a population of two males and two females (one of them with at least two cubs) in an area of 600 km2 (0.63 cougars per 100 km2).[35] The Bay Area Puma Project aims to obtain information on cougar populations in the San Francisco Bay area and the animals' interactions with habitat, prey, humans, and residential communities.[36] A study on wildlife ecologists showed that urban cougar populations exist around the Los Angeles metropolitan area, with individuals of these populations having the smallest home ranges recorded for any cougars studied, and being primarily nocturnal and not crepuscular (most likely adaptations to avoid humans in high-density areas).[37]

Communication and behavior

Cougars are intelligent animals that rely on strategy when it comes to various means of survival. Through scent, noises, and posture, cougars communicate with each other to exchange messages. Each message depends on how the cougar delivers the sound. If a cougar growls or hisses, other cougars understand a threat is present. The ‘caterwaul’ is a screeching sound made by female cougars during the mating season when competing males are present.[23] Cougars use various methods to signal and communicate with each other. When cougars perceive a looming threat or danger nearby, they lay their ears back and either maintain eye contact or retreat to a less visible location in preparation to attack.[38]

See also

- Shasta (mascot)

- South American cougar

- American cheetah (extinct species related to the cougar, despite its name)

- Felinae

References

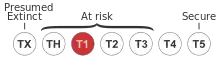

- ↑ "Puma concolor". explorer.natureserve.org.

Canada: N5, United States: N5

- ↑ "Puma concolor browni". explorer.natureserve.org.

- 1 2 Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Subspecies Puma concolor couguar". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 544–545. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Barrett, J. (1998). Cougar. Blackbirch Press. ISBN 1567112587.

- 1 2 Rodrigo Nuanaez; Brian Miller; Fred Lindzey (2000). "Food habits of jaguars and pumas in Jalisco, Mexico". Journal of Zoology. 252 (3): 373–379. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2000.tb00632.x. Retrieved 2006-08-08.

- 1 2 Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 33–34.

- 1 2 3 "Cougar Subspecies". Panthera. Archived from the original on 2014-05-31. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- 1 2 Sunquist, Mel; Sunquist, Fiona (2002). Wild Cats of the World. The University of Chicago Press. p. 452. ISBN 0-226-77999-8.

- 1 2 Lang, Le Duing; Tessier, Nathalie; Gauthier, Marc; Wissink, Renee; Jolicoeur, Hélène; Lapointe, François-Joseph (September 2013). "Genetic Confirmation of Cougars ( Puma concolor ) in Eastern Canada". Northeastern Naturalist. 20 (3): 383–396. doi:10.1656/045.020.0302. S2CID 84214196.

- ↑ "Your part in helping endangered species". Ministry of Wildlife and Natural Resources, Quebec, Canada. 2010. Archived from the original on February 3, 2011. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ↑ Davidson, Rick (2009). "NH Sightings Catamount" (PDF). Beech River Books. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 7, 2009. Retrieved March 20, 2009.

- ↑ Dellinger, Justin A.; Torres, Steven G. (2020-01-05). "A retrospective look at mountain lion populations in California (1906–2018)". California Fish and Wildlife Journal. 106 (1). doi:10.51492/cfwj.106.6. ISSN 2689-4203. S2CID 250398737.

- 1 2 Pridgen, Andrew (2022-10-05). "How California created a 'genetic mix-up' of mountain lion population". SFGATE. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ↑ Mountain lion killed in Conn. had walked from S. Dakota. Content.usatoday.com (2011-07-26). Retrieved on 2012-12-29.

- ↑ Manier, Jeremy; Shah, Tina (15 April 2008). "Cops kill cougar on North Side". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ↑ Times Staff (22 November 2013). "Cougar shot in Whiteside County". Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Barghouthi, Hani (November 7, 2021). "Do increased cougar sightings mean more are roaming Michigan?". The Detroit News. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ↑ "Cougars in Tennessee - TN.Gov". www.tn.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- ↑ "Hills Mountain Lion May Have Migrated To Wisconsin". CougarNetwork. Archived from the original on 2008-05-22. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ↑ "Cougars in Wisconsin". Retrieved 2013-11-22.

- ↑ Becker, Amanda (November 10, 2021). "Wisconsin DNR confirms West Bend trail camera picture is a cougar". CBS58. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ↑ "Northeast Confirmation Reports". CougarNetwork. Archived from the original on 2007-07-31. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Cougar Biology & Behavior". Western Wildlife Outreach. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- 1 2 3 "Eastern Cougars Declared Extinct—But That Might Not be Bad". Animals. 2018-01-25. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ↑ Gutiérrez-González, Carmina E.; López-González, Carlos A. (2017). "Jaguar interactions with pumas and prey at the northern edge of jaguars' range". PeerJ. 5: e2886. doi:10.7717/peerj.2886. PMC 5248577. PMID 28133569.

- ↑ Grant, Richard (October 2016). "The Return of the Great American Jaguar". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ↑ Servheen, C.; Herrero, S.; Peyton, B. (1999). Bears: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan (PDF). Missoula, Montana: IUCN/SSC Bear Specialist Group. ISBN 978-2-8317-0462-3.

- ↑ "JWM: Cougars prey on feral horses in the Great Basin". 20 August 2021.

- ↑ "DO COUGARS AFFECT ECOSYSTEMS BY PREYING ON FERAL DONKEYS?". 10 May 2023.

- ↑ Tracy Irwin Storer; Lloyd Pacheco Tevis (1996). California Grizzly. University of California Press. pp. 71–151. ISBN 978-0-520-20520-8.

- ↑ "Threats". WildFutures. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ↑ "Cougar Management Plan". Wildlife Division: Wildlife Management Plans. Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. 2006. Archived from the original on June 30, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ↑ "Mountain Lions in California". California Department of Fish and Game. 2004. Archived from the original on April 30, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ↑ Ernest, Holly B.; Vickers, T. Winston; Morrison, Scott A.; Buchalski, Michael R.; Boyce, Walter M. (2014). "Fractured Genetic Connectivity Threatens a Southern California Puma (Puma concolor) Population". PLOS ONE. 9 (10): e107985. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j7985E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107985. PMC 4189954. PMID 25295530.

- ↑ Research of Nicolás Guarda, supported by Conaf, Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, and a private enterprise. See article in Chilean newspaper La Tercera, Investigación midió por primera vez población de pumas en zona central Archived January 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on January 28, 2013, in Spanish Language.

- ↑ "Bay Area Puma Project (BAPP)". Felidae Conservation Fund. Archived from the original on March 23, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- ↑ Walker, Elicia (October 25, 2021). "Big cats adapt to city life". wildlife.org. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ↑ "Understanding a Mountain Lion's "Body Language"". www.hunter-ed.com. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- Sources

- Wright, Bruce S. The Eastern Panther: A Question of Survival. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin and Company, 1972.

External links

- Eastern Cougar Foundation

- National Heritage Information Centre: General Element Report: Puma concolor Archived 2015-09-04 at the Wayback Machine

- New York State Department of Environmental Conservation: Eastern Cougar Fact Sheet

- The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

- Photograph of a black or dark cougar in Costa Rica

- Largest North American Cat: Mountain Lion (Cougar)