| Chukchi Sea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | North Asia and Northern America |

| Coordinates | 69°N 172°W / 69°N 172°W |

| Type | Sea |

| Basin countries | Russia and United States |

| Surface area | 620,000 km2 (240,000 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 80 m (260 ft) |

| Water volume | 50,000 km3 (4.1×1010 acre⋅ft) |

| References | [1][2][3] |

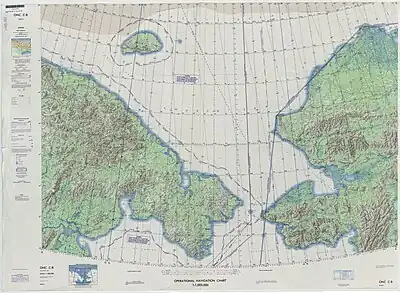

The Chukchi Sea (Russian: Чуко́тское мо́ре, romanized: Chukótskoye móre, IPA: [tɕʊˈkotskəjə ˈmorʲe]), sometimes referred to as the Chuuk Sea, Chukotsk Sea[4] or the Sea of Chukotsk,[5] is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is bounded on the west by the Long Strait, off Wrangel Island, and in the east by Point Barrow, Alaska, beyond which lies the Beaufort Sea. The Bering Strait forms its southernmost limit and connects it to the Bering Sea and the Pacific Ocean. The principal port on the Chukchi Sea is Uelen in Russia. The International Date Line crosses the Chukchi Sea from northwest to southeast. It is displaced eastwards to avoid Wrangel Island as well as the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug on the Russian mainland.

Geography

The sea has an approximate area of 595,000 square kilometres (230,000 sq mi) and is only navigable about four months of the year. The main geological feature of the Chukchi Sea bottom is the 700-kilometer-long (430 mi) Hope Basin, which is bound to the northeast by the Herald Arch. Depths less than 50 meters (160 ft) occupy 56% of the total area.

The Chukchi Sea has very few islands compared to other seas of the Arctic. Wrangel Island lies at the northwestern limit of the sea, Herald Island is located off Wrangel Island's Waring Point, near the northern limit of the sea. A few small islands lie along the Siberian and Alaskan coasts.

The sea is named after the Chukchi people, who reside on its shores and on the Chukotka Peninsula. The coastal Chukchi traditionally engaged in fishing, whaling and the hunting of walrus in this cold sea.

In Siberia places along the coast are: Cape Billings, Cape Schmidt, Amguyema River, Cape Vankarem, the large Kolyuchinskaya Bay, Neskynpil'gyn Lagoon, Cape Serdtse-Kamen, Enurmino, Chegitun River, Inchoun, Uelen and Cape Dezhnev.

In Alaska, the rivers flowing into the Chukchi Sea are the Kivalina, the Kobuk, the Kokolik, the Kukpowruk, the Kukpuk, the Noatak, the Utukok, the Pitmegea, and the Wulik, among others. Of rivers flowing in from its Siberian side, the Amguyema, Ioniveyem, and the Chegitun are the most important.

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the "Chuckchi Sea" [sic] as follows:[6]

On the West. The Eastern limit of East Siberian Sea [From the Northernmost point of Wrangel Island through this island to Blossom Point thence to Cape Yakan on the mainland (176°40′E)].

On the North. A line from Point Barrow, Alaska (71°20′N 156°20′W / 71.333°N 156.333°W) to the Northernmost point of Wrangel Island (179°30'W).

On the South. The Arctic Circle [66°33′46″N] between Siberia and Alaska. [The northern limit of the Bering Sea.]

Common usage is that the southern extent is further south, at the narrowest part of the Bering Strait which is on the 66th parallel north.

Chukchi Sea Shelf

The Chukchi Sea Shelf is the westernmost part of the continental shelf of the United States and the easternmost part of the continental shelf of Russia. Within this shelf, the 50-mile (80 km) Chukchi Corridor acts as a passageway for one of the largest marine mammal migrations in the world. Species that have been documented migrating through this corridor include the bowhead whale, beluga whale, Pacific walrus, and bearded seals[7][8][9]

History

In 1648, Semyon Dezhnyov sailed from the Kolyma River on the Arctic to the Anadyr River on the Pacific, but his route was not practical and was not used for the next 200 years. In 1728, Vitus Bering and in 1779, Captain James Cook entered the sea from the Pacific.

On 28 September 1878, during Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld's expedition that made the whole length of the Northeast passage for the first time in history, the steamship Vega got stuck in fast ice in the Chukchi Sea. Since further progress for that year was impossible, the ship was secured in winter quarters. Even so, members of the expedition and the crew were aware only a few miles of ice-blocked sea lay between them and the open waters. The following year, two days after Vega was released, she passed the Bering Strait and steamed towards the Pacific Ocean.

In 1913, Karluk, abandoned by expedition leader Vilhjalmur Stefansson, drifted in the ice along the northern expanses of the Chukchi Sea and sank, crushed by ice near Herald Island. The survivors made it to Wrangel Island, where they found themselves in a hopeless situation. Then Captain Robert Bartlett walked hundreds of kilometers with Kataktovik, an Inuit man, on the ice of the Chukchi Sea in order to look for help. They reached Cape Vankarem on the Chukotka coast, on April 15, 1914. Twelve survivors of the ill-fated expedition were found on Wrangel island nine months later by the King & Winge, a newly built Arctic fishing schooner.

In 1933, the steamer Chelyuskin sailed from Murmansk, east bound to attempt a transit of the Northern Sea Route to the Pacific, in order to demonstrate such a transit could be achieved in one season. The vessel became beset in heavy ice in the Chukchi Sea, and after drifting with the ice for over two months, was crushed and sank on 13 February 1934 near Kolyuchin Island. Apart from one fatality, her entire complement of 104 was able to establish a camp on the sea ice. The Soviet government organized an impressive aerial evacuation, under which all were rescued. Captain Vladimir Voronin and expedition leader Otto Schmidt became heroes.

Following several unsuccessful attempts, the wreck was located on the bed of the Chukchi Sea by a Russian expedition, Chelyuskin-70, in mid-September 2006. Two small components of the ship's superstructure were recovered by divers and were sent to the ship's builders, Burmeister & Wain of Copenhagen, for identification.

In July 2009, a large mass of organic material was found floating in the sea off the northwest Alaskan coast. Analysis by the U.S. Coast Guard has identified it as a large body of algal bloom.

On 15 October 2010, Russian scientists opened a floating polar research station in the Chukchi Sea at the margin of the Arctic Ocean. The name of the station was Severny Polyus-38 and it was home to 15 researchers for a year. They conducted polar studies and gathered scientific evidence to reinforce Russia's claims to the Arctic.[10]

Fauna

The polar bears living on the pack ice of the Chukchi Sea are one of the five genetically distinct Eurasian populations of the species.[11]

Phytoplankton

In 2012, scientists from the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory published findings describing the discovery of the largest-known oceanic phytoplankton algal bloom in the world. The findings were unexpected as it was previously believed that the plankton grows only after the seasonal ice melt, yet some algae was discovered under several metres of intact sea ice.[12]

Anderson et al 2021 documents two cyst beds of the dinoflagellate Alexandrium catenella in Ledyard Bay and Barrow Canyon within the Chukchi sea.[13] Although the cyst beds consist of A. catenella in a dormant state, if environmental conditions are right, they can germinate and create harmful algal blooms. In its active state, A. catenella produces saxitoxin, a potent neurotoxin that is responsible for paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) if consumed. The toxin can bioaccumulate through the food-chain and poses a threat to local communities that rely on the marine food web for sustenance.[14]

The total area of the cyst beds is 145,600 km2, comparable to the area of the state of Iowa. These beds are six times larger than previously reported beds in other areas, and cyst concentration in the sediment is among the highest globally. Germination can only occur in the upper few millimeters of a bed, as cysts must be in oxic conditions to enter their more active life stage in which reproduction is possible.[13]

At bottom water temperatures of approximately 3 °C, A. catenella cysts take approximately 28 days to germinate, and at bottom water temperatures of 8°, the germination time is shortened to 10 days. In situ blooms in 2018 and 2019 have been attributed to these cyst beds and occurred in the months of July and August. With warmer summer water temperatures and increasingly destabilized oceanic currents associated with climate change, bloom initiation has been advanced by three weeks over the last two decades, and the time window for harmful surface blooms has been extended.[13]

Oil and gas resources

The Chukchi shelf is believed to hold oil and gas reserves as high as 30 billion barrels (4.8×109 m3). Several oil companies have competed for leases on the area, and on 6 February 2008, the U.S. government announced the successful bidders would pay US$2.6 billion for extraction rights. The auction drew considerable criticism from environmentalists.[15] In May 2015, the Obama administration's Bureau of Ocean Energy Management gave a conditional approval for Shell Oil to drill in shallow (140 ft [43 m] deep) Chukchi Sea waters.[16] In September 2015, Shell announced that it was ending its oil exploration in the region, citing tremendous cost and declining oil prices.[17] Shell vowed to return, but eventually gave up all but one of the corporation's leases in the Arctic.[18]

See also

References

- ↑ R. Stein, Arctic Ocean Sediments: Processes, Proxies, and Paleoenvironment, p. 37

- ↑ Beaufort Sea, Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian)

- ↑ Beaufort Sea, Encyclopædia Britannica on-line

- ↑ "education.rec.org Seas and Oceans: The Chukotsk Sea". Archived from the original on 2021-10-17. Retrieved 2019-04-11.

- ↑ Owen, Richard (15 October 1983). "Race against time to save ice-bound ships". The Times. No. 61664. London. col D, p. 6.

- ↑ "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ↑ Quakenbush L., R. Small, and J. Citta, "Satellite tracking of bowhead whales: Movements and analysis from 2006 to 2012", Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Outer Continental Shelf Study, 2013. Retrieved 16-09-2016.

- ↑ Suydam R., F. Lowry, and K. Frost, "Distribution and Movements of Beluga Whales from the Eastern Chukchi Sea Stock During Summer and Early Autumn" Archived 2016-06-23 at the Wayback Machine, Coastal Marine Institute and US Department of Interior, Minerals Management Service, 2005. Retrieved 16-09-2016.

- ↑ Berchok C., J. Crance, E. Garlan, J. Mocklin, P. Stabeno, J. Napp, B. Rone, A. Spear, M. Wang, and C. Clark, "Chukchi Offshore Monitoring In Drilling Area (COMIDA): Factors Affecting the Distribution and Relative Abundance of Endangered Whales and Other Marine Mammals in the Chukchi Sea", Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Outer Continental Shelf Study, 2015. Retrieved 16-09-2016.

- ↑ Russian Drifting Polar Station SP-38 Opens In Chukchi Sea, RIA Novosti, 8 November 2010

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan (2008) Polar Bear: Ursus maritimus, Globaltwitcher.com, ed. N. Stromberg Archived December 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Huge algae blooms discovered beneath Arctic ice - The Times of India". timesofindia.indiatimes.com. Archived from the original on 2012-06-12.

- 1 2 3 Anderson, Donald M.; Fachon, Evangeline; Pickart, Robert S.; Lin, Peigen; Fischer, Alexis D.; Richlen, Mindy L.; Uva, Victoria; Brosnahan, Michael L.; McRaven, Leah; Bahr, Frank; Lefebvre, Kathi; Grebmeier, Jacqueline M.; Danielson, Seth L.; Lyu, Yihua; Fukai, Yuri (12 October 2021). "Evidence for massive and recurrent toxic blooms of Alexandrium catenella in the Alaskan Arctic". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (41): e2107387118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11807387A. doi:10.1073/pnas.2107387118. PMC 8521661. PMID 34607950.

- ↑ "There's a Toxic, California-Sized Algae Bed Creeping into the Arctic".

- ↑ "'Chukchi Sea Lease Sale Is a Risky Fix for Our Oil Addiction' (Anchorage News, February 8, 2008)". Archived from the original on July 19, 2009. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- ↑ Davenport, Coral (11 May 2015). "Administration Gives Conditional Approval for Shell to Drill in Arctic". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ↑ Krauss, Clifford; Reed, Stanley (28 September 2015). "Shell Exits Arctic as Slump in Oil Prices Forces Industry to Retrench". The New York Times.

- ↑ "As firms abandon Arctic drilling, Obama comes under pressure to do more to avert dangerous warming there". The Washington Post.

Further reading

- Polyak, Leonid; Darby, Dennis A.; Bischof, Jens F.; Jakobsson, Martin (March 2007). "Stratigraphic constraints on late Pleistocene glacial erosion and deglaciation of the Chukchi margin, Arctic Ocean". Quaternary Research. 67 (2): 234–245. Bibcode:2007QuRes..67..234P. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2006.08.001. S2CID 23107907.

- Albert Hastings Markham. Arctic Exploration, 1895

- Armstrong, T., The Russians in the Arctic, London, 1958.

- William Barr, Discovery of the wreck of the Soviet steamer Chelyuskin on the bed of the Chukchi Sea

- Early Soviet Exploration

- History of Russian Arctic Exploration

- Niven, J., The Ice Master, The Doomed 1913 Voyage of the Karluk.

- Polynyas in the Chukchi Sea:

- Polar bear protection in the Chukchi Sea: Polar bears shared by US, Russia to be managed jointly

- Vinogradov V.A., Gusev E.A., Lopatin B.G. Structure of the Russian Eastern Arctic Shelf:

External links

- Ecological assessment Archived 2006-09-30 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- Audubon Alaska's Arctic Marine Synthesis: Atlas of the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas