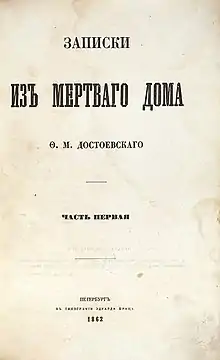

First separate edition (1862) | |

| Author | Fyodor Dostoevsky |

|---|---|

| Original title | Записки из Мёртвого дома (Zapiski iz Myortvovo doma) |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Semi-autobiographical novel, philosophical novel |

| Publisher | Vremya |

Publication date | 1860–1862 |

| Pages | 368 |

The House of the Dead (Russian: Записки из Мёртвого дома, Zapiski iz Myortvovo doma) is a semi-autobiographical novel published in 1860–2[1] in the journal Vremya[2] by Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky. It has also been published in English under the titles Notes from the House of the Dead, Memoirs from the House of the Dead and Notes from a Dead House, which are more literal translations of the Russian title.

The novel portrays the life of convicts in a Siberian prison camp. It is generally considered to be a fictionalised memoir; a loosely-knit collection of descriptions, events and philosophical discussion, organised around theme and character rather than plot, based on Dostoevsky's own experiences as a prisoner in such a setting. Dostoevsky spent four years in a forced-labour prison camp in Siberia following his conviction for involvement in the Petrashevsky Circle. This experience allowed him to describe with great authenticity the conditions of prison life and the characters of the convicts.

Background

After his mock execution on 22 December 1849, Dostoevsky was sentenced to four years imprisonment in a katorga labor camp at Omsk in western Siberia. Though he often was met with hostility from the other prisoners due to his noble status of dvoryanin, his views on life changed. After his time in the camps and a further six years of exile Dostoevsky returned to Petersburg and wrote The House of the Dead. The novel incorporates several of the horrifying experiences he witnessed while in prison. He recalls the guards' brutality and relish performing unspeakably cruel acts, the crimes that the convicted criminals committed, and the fact that among these hardened criminals there were good and decent individuals.[3] However, he is also astonished at the convicts' abilities to commit murders without the slightest change in conscience. It was a stark contrast to his own heightened sensitivity. During this time in prison he began experiencing the epileptic seizures that would plague him for the rest of his life.

Plot

The narrator, Aleksandr Petrovich Goryanchikov, has been sentenced to deportation to Siberia and ten years of hard labour for murdering his wife. Life in prison is particularly hard for Aleksandr Petrovich, since he is a "gentleman" and suffers the malice of the other prisoners, nearly all of whom belong to the peasantry. Gradually Goryanchikov overcomes his revulsion at his situation and his fellow convicts, undergoing a spiritual awakening that culminates with his release from the camp. Dostoevsky portrays the inmates of the prison with sympathy for their plight, and also expresses admiration for their courage, energy, ingenuity and talent. He concludes that the existence of the prison, with its absurd practices and savage corporal punishments, is a tragic fact, both for the prisoners and for Russia.

Though the novel has no readily identifiable plot in the conventional sense, events and descriptions are carefully organized around the narrator's gradual insight into the true nature of the prison-camp and the other prisoners. It is primarily in this sense that the novel is autobiographical: Dostoevsky wrote later, in A Writer's Diary and elsewhere, about the transformation he underwent during his imprisonment, as he slowly overcame his preconceptions and his repulsion, attaining a new understanding of the intense humanity and moral qualities of those around him.[4]

Narration

The first chapter, entitled "Ten years a convict", is an introduction written by an unnamed acquaintance of Goryanchikov. This narrator discusses Goryanchikov's background as a convict, his crime and his sentence, and the nature of his life as a Siberian colonist after his release. He describes Goryanchikov's intense personality and reclusive behaviour from the superficial and detached perspective of a new acquaintance who has developed a curiosity about him. He records that, upon hearing of Goryanchikov's death, he had managed to acquire some papers from the landlady, among which were the memoirs of prison life. He describes them as "incoherent and fragmentary... interrupted, here and there, either by anecdotes, or by strange, terrible recollections thrown in convulsively as if torn from the writer."[5] These memoirs, with Goryanchikov himself narrating, constitute the rest of the novel.

Characters

Many of the characters in the novel were based on real-life people that Dostoevsky met while in prison. However, there was a degree of alteration or embellishment in some characters and events for the sake of imparting greater depth to his themes.[6]

The Major, the violent-tempered, tyrannical governor of the prison. He is described by Alexander Petrovich as "a spiteful, ill-regulated man, terrible above all things, because he possessed almost absolute power over two hundred human beings." Referred to by the prisoners as "the man with the eight eyes" due to his apparent omniscience, he is universally despised and feared.

Akim Akimitch, one of the few other noblemen in the prison, befriends Alexander Petrovich and teaches him about the ways of prison life. He is a former officer who was sentenced for unilaterally ordering an illegal execution. Alexander Petrovich considers Akim Akimitch to be incapable of independent intelligence and wholly bound to notions of duty and obedience. He is conscientious, precise, excitable and argumentative, and assumes the role of a moral remonstrator with the other convicts, who, while afraid of him, also laugh at him and consider him a bit mad.

A parricide. The second convict Alexander Petrovich mentions is not referred to by name, but his character and crime (killing his father to obtain his inheritance) are discussed in some detail. He is described as always "in the liveliest, merriest spirits", and unwavering in his denial of his guilt, a denial that Goryanchikov is inclined to believe. The real life person upon whom this character was based (D. I. Ilyinsky) was later freed after another man confessed to the crime. The main elements of his story became the central theme of The Brothers Karamazov and the initial inspiration for the character of Dimitri Karamazov.[7]

Aristov an exceptionally corrupt and perverted nobleman who acts as a spy and informer. Repelled by his depravity, Alexander Petrovich refuses to enter in to relations with him. He is a man utterly submitted to corporeality and the basest impulses, with a conscience guided only by cold calculation. Alexander Petrovich says of him that "if he wanted a drink of brandy, and could only have got it by killing some one, he would not have hesitated one moment if it was pretty certain the crime would not come out."

Gazin, an immensely strong, violent criminal, in prison for, among other things, torturing and murdering small children. He creates a shocking and repulsive impression on everyone else. According to Alexander Petrovich: "It was less by his great height and his herculean construction, than by his enormous and deformed head, that he inspired terror."

Orloff, a notorious criminal and escapee, who Alexander Petrovich describes as "a brilliant example of the victory of spirit over matter", unlike some other prisoners whose fearfulness proceeded more from their complete submission to matter. He undergoes extreme corporal punishment but is unbowed and quickly recovers his strength and spirit.

Luka has murdered six people, occasionally brags of it, and wishes to be feared for it, but in fact no-one in the prison is the least bit afraid of him. For Alexander Petrovich he represents a particular type:

When once he has passed the fatal line, he is himself astonished to find that nothing sacred exists for him. He breaks through all laws, defies all powers, and gives himself boundless license... From time to time, the murderer will amuse himself by recalling his audacity, his lawlessness when he was in a state of despair. He likes at these moments to have some silly fellow before whom he can brag... "That is the sort of man I am," he says.

Petrov, an externally quiet and polite man who befriends Alexander Petrovich and often seeks his company, apparently for edification on matters of knowledge. Alexander Petrovich finds it hard to reconcile Petrov's sincere friendship and unfailing courtesy with the ever-present potential (attributed to him by all the other prisoners, including Alexander Petrovich) for the most extreme violence. In this sense, Petrov is thought to be the most dangerous and determined man in the prison.

Ali a beautiful-souled young Tatar, imprisoned with his two older brothers. He has a gentle and innocent yet strong and stoical nature, and is much beloved by Alexander Petrovich and many of the others. "How this young man preserved his tender heart, his native honesty, his frank cordiality without getting perverted and corrupted during his period of hard labour, is quite inexplicable."

Isaiah Fomitch a Jew who becomes a great friend of Alexander Petrovich. He is small, feeble and cunning, capable of both abject cowardice and great courage, laughed at constantly by the other prisoners, but at the same time "inexhaustibly good humoured". He has scars on his forehead and cheeks from burns received while in the pillory. In the bath-room scene, where all the convicts are crowded together for a steam bath, Alexander Petrovich describes the hellish chaos of bodies, heat and steam:

From this cloud stood out torn backs, shaved heads; and, to complete the picture, Isaiah Fomitch howling with joy on the highest of the benches. He was saturating himself with steam. Any other man would have fainted away, but no temperature is too high for him; he engages the services of a rubber for a kopeck, but after a few moments the latter is unable to continue, throws away his bunch of twigs, and runs to inundate himself with cold water. Isaiah Fomitch does not lose courage, he runs to hire a second rubber, then a third; on these occasions he thinks nothing of expense, and changes his rubber four or five times. "He stews well, the gallant Isaiah Fomitch," cry the convicts from below. The Jew feels that he goes beyond all the others, he has beaten them; he triumphs with his hoarse falsetto voice, and sings out his favourite air which rises above the general hubbub.

Reception

The House of the Dead was the only work by Dostoevsky that Leo Tolstoy revered.[8] He saw it as exalted religious art, inspired by deep faith and love of humanity.[9][10] Turgenev, who was also not enamored of Dostoevsky's larger scale fiction (particularly Demons and Crime and Punishment), described the bath-house scene from House of the Dead as "simply Dantesque".[11][12] Herzen echoed the comparison to Dante and further compared the description of Siberian prison life to "a fresco in the spirit of Michelangelo".[11] Frank suggests that the memoir-novel's popularity with those who might ordinarily be antipathetic to Dostoevsky's prose style, is due to the composed and neutral tone of its narration and the vividness of the descriptive writing: "The intense dramatism of the fiction is here replaced by a calm objectivity of presentation; there is little close analysis of interior states of mind, and there are marvelous descriptive passages that reveal Dostoevsky's ability as an observer of the external world."[11]

Editions

English translations

- Fedor Dostoyeffsky (1862). Buried Alive: or, Ten Years Penal Servitude in Siberia. Translated by von Thilo, Marie. London: Longman's, Green, and Co. (published 1881).

- Fedor Dostoïeffsky (1862). Prison Life in Siberia. Translated by Edwards, H. Sutherland. London: J. & R. Maxwell (published 1888).

- Fyodor Dostoevsky (1862). The House of the Dead: or, Prison Life in Siberia; A Novel in Two Parts. Translated by Garnett, Constance. New York: The Macmillan Company (published 1915).

- Fyodor Dostoevsky (1862). Notes from a Dead House. Translated by Navrozov, Lev. Moscow: Foreign Language Publishing House (published 1950).

- Fyodor Dostoevsky (1862). Memoirs from the House of the Dead. Translated by Coulson, Jessie. Oxford University Press, Oxford World's Classics (published 1983). ISBN 9780199540518.

- Fyodor Dostoevsky (1862). The House of the Dead. Translated by McDuff, David. Penguin Classics (published 1985). ISBN 9780140444568.

- Fyodor Dostoevsky (1862). Notes from the House of the Dead. Translated by Jakim, Boris. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. (published 2013). ISBN 978-0802866479.

- Fyodor Dostoevsky (1862). Notes from a Dead House. Translated by Pevear, Richard; Volokhonsky, Larissa. Vintage Books (published 2016). ISBN 978-0-307-94987-5.

- Fyodor Dostoevsky (1862). The House of the Dead. Translated by Cockrell, Roger. Alma Classics (published 2018). ISBN 978-1-84749-666-9.

Adaptations

In 1927–1928, Leoš Janáček wrote an operatic version of the novel, with the title From the House of the Dead. It was his last opera.

In 1932 The House of the Dead was made into a film, directed by Vasili Fyodorov and starring Nikolay Khmelyov. The script was devised by the Russian writer and critic Viktor Shklovsky who also had a role as an actor.

See also

References

- ↑ The first part was published in 1860 and the second one in 1862. The novel's first complete appearance was in book form in 1862.

- ↑ See the Introduction by Joseph Frank in Dostoevsky, Fyodor (2004). The House of the Dead and Poor Folk. Translated by Constance Garnett. Barnes and Noble. ISBN 9781593081942.

- ↑ Morson, Gary Saul (2023). "Fyodor Dostoevsky". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Frank (2010), p. 365.

- ↑ Dostoevsky, Fyodor (1915). The House of the Dead. Translated by Constance Garnett. William Heinemann. p. 6. ISBN 9780434204069.

- ↑ Frank (2010), p. 197.

- ↑ Frank (2010), p. 204.

- ↑ Rayfield, Donald (29 Sep 2016). "The House of the Dead by Daniel Beer review – was Siberia hell on earth?". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ↑ Frank (2010), p. 369.

- ↑ Tolstoy, L.N.; Maude, Louise and Aylmer (1951). Tales from Army Life. p. 105.

- 1 2 3 Frank (2010), p. 368.

- ↑ Turgenev, Ivan (1961). Letters, 13 vols. p. 6:66.

- Frank, Joseph (2010). Dostoevsky A Writer In His Time. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691128191.

External links

- Compare English translations of The House of the Dead at the Wayback Machine

- Full text of The House of the Dead in the original Russian

- Full text of The House of the Dead in English at the Internet Archive

- The House of the Dead at Project Gutenberg

The House of the Dead public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The House of the Dead public domain audiobook at LibriVox