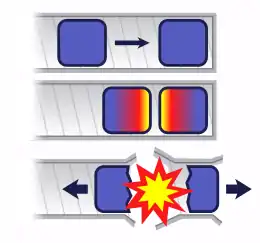

A fizzle occurs when the detonation of a device for creating a nuclear explosion (such as a nuclear weapon) grossly fails to meet its expected yield. The bombs still detonate, but the detonation is much less than anticipated. The cause(s) for the failure can be linked to improper design, poor construction, or lack of expertise.[1][2] All countries that have had a nuclear weapons testing program have experienced some fizzles.[3] A fizzle can spread radioactive material throughout the surrounding area, involve a partial fission reaction of the fissile material, or both.[4] For practical purposes, a fizzle can still have considerable explosive yield when compared to conventional weapons.

In multistage fission-fusion weapons, full yield of the fission primary that fails to initiate fusion ignition in the fusion secondary (or produces only a small degree of fusion) is also considered a "fizzle", as the weapon failed to reach its design yield despite the fission primary working correctly. Such fizzles can have very high yields, as in the case of Castle Koon, where the secondary stage of a device with a 1 megaton design fizzled, but its primary still generated a yield of 100 kilotons, and even the fizzled secondary still contributed another 10 kilotons, for a total yield of 110 kT.

Fusion boosting

If a deuterium-tritium mixture is placed at the center of the device to be compressed and heated by the fission explosion, a fission yield of 250 tons is sufficient to cause D-T fusion releasing high-energy fusion neutrons which will then fission much of the remaining fission fuel. This is known as a boosted fission weapon.[5] If a fission device designed for boosting is tested without the boost gas, a yield in the sub-kiloton range may indicate a successful test that the device's implosion and primary fission stages are working as designed, though this does not test the boosting process itself.

Nuclear fission tests considered to be fizzles

- Buster Able

- Considered to be the first known failure of any nuclear device.[6]

- Upshot–Knothole Ruth

- Testing a uranium hydride bomb. The test failed to declassify the site (erase evidence) as it left the bottom third of the 300-foot (91 m) shot tower still standing.[7]

- Upshot–Knothole Ray

- Similar test conducted the following month. Allegedly a shorter 100-foot (30 m) tower was chosen, to ensure that the tower would be completely destroyed.[7]

- North Korean nuclear test in 2006

- Russia claimed to have measured 5–15 kt yield, whereas the United States, France, and South Korea measured less than 1 kt yield.[8] This North Korean debut test was weaker than all other countries' initial tests by a factor of 20,[9] and the smallest initial test in history.[10]

Nuclear fusion tests that fizzled

- Castle Koon

- A thermonuclear device whose fusion secondary did not successfully ignite, with only low-level fusion burning taking place.

- Short Granite

- Dropped by the United Kingdom over Malden Island in the Pacific on May 15, 1957, during Operation Grapple 1, this bomb had an expected yield of over 1 megaton, but only exploded with a force of a quarter of the anticipated yield.[3] The test was still considered successful, as thermonuclear ignition occurred and contributed substantially to the bomb's yield. Another bomb dropped during Grapple 1, Purple Granite, was hoped to give an improved yield over Short Granite, but the yield was even lower.

Terrorist concerns

One month after the September 11, 2001 attacks, a CIA informant known as "Dragonfire" reported that al-Qaeda had smuggled a low-yield nuclear weapon into New York City.[11] Although the report was found to be false, concerns were expressed that even a "fizzle bomb" capable of yielding a fraction of the known 10-kiloton weapons could cause "horrific" consequences. A detonation in New York City would mean thousands of civilian casualties.[2][12]

See also

References

- ↑ Staff Writer. "NBC Weapons: North Korean Fizzle Bomb." Strategy Page. Retrieved on 2008-05-04.

- 1 2 Earl Lane. "Nuclear Experts Assess the Threat of a "Backyard Bomb”." American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved on 2008-05-04. Archived May 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Meirion Jones." A short history of fizzles." BBC News. Retrieved on 2008-05-04.

- ↑ Theodore E. Liolios." The Effects of Nuclear Terrorism: Fizzles." (PDF) European Program on Science and International Security. Retrieved on 2008-05-04.

- ↑ http://nuclearweaponarchive.org/News/DoSuitcaseNukesExist.html Nuclear Weapon Archive, Carey Sublette: Are Suitcase Bombs Possible?

- ↑ Carey Sublette. "Operation Buster-Jangle 1951." Nuclear Weapon Archive. Retrieved on 2008-05-04.

- 1 2 Carey Sublette. "Operation Upshot-Knothole 1953 - Nevada Proving Ground." Nuclear Weapon Archive. Retrieved on 2008-05-04.

- ↑ Penny Spiller." N Korea test - failure or fake?." BBC News. Retrieved on 2008-05-04.

- ↑ Todd Crowell." A deadly kind of fizzle." Asia Times Online. Retrieved on 2008-05-04.

- ↑ Staff Writer. "Special report -The fizzle heard around the world." Nature.com. Retrieved on 2008-05-04.

- ↑ Nicholas D. Kristof. "An American Hiroshima." The New York Times. Published August 11, 2004. Retrieved on 2008-05-04.

- ↑ Michael A. Levi" How Likely is a Nuclear Terrorist Attack on the United States? Archived 2008-05-02 at the Wayback Machine." Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved on 2008-05-04.

External links

- Not a bomb or a dud but a fizzle Ian Hoffman, Oakland Tribune, October 9, 2006.

- Nuclear Weapons, howthingswork.virginia.edu