In organic chemistry, a nucleophilic addition reaction is an addition reaction where a chemical compound with an electrophilic double or triple bond reacts with a nucleophile, such that the double or triple bond is broken. Nucleophilic additions differ from electrophilic additions in that the former reactions involve the group to which atoms are added accepting electron pairs, whereas the latter reactions involve the group donating electron pairs.

Addition to carbon–heteroatom double bonds

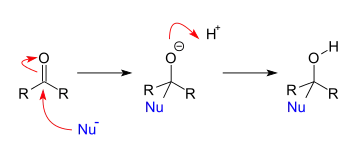

Nucleophilic addition reactions of nucleophiles with electrophilic double or triple bond (π bonds) create a new carbon center with two additional single, or σ, bonds.[1] Addition of a nucleophile to carbon–heteroatom double or triple bonds such as >C=O or -C≡N show great variety. These types of bonds are polar (have a large difference in electronegativity between the two atoms); consequently, their carbon atoms carries a partial positive charge. This makes the molecule an electrophile, and the carbon atom the electrophilic center; this atom is the primary target for the nucleophile. Chemists have developed a geometric system to describe the approach of the nucleophile to the electrophilic center, using two angles, the Bürgi–Dunitz and the Flippin–Lodge angles after scientists that first studied and described them.[2][3][4]

This type of reaction is also called a 1,2-nucleophilic addition. The stereochemistry of this type of nucleophilic attack is not an issue, when both alkyl substituents are dissimilar and there are not any other controlling issues such as chelation with a Lewis acid, the reaction product is a racemate. Addition reactions of this type are numerous. When the addition reaction is accompanied by an elimination the reaction type is nucleophilic acyl substitution or an addition-elimination reaction.

Addition to carbonyl groups

With a carbonyl compound as an electrophile, the nucleophile can be:[1]

- water in hydration to a geminal diol (hydrate)

- an alcohol in acetalisation to an acetal

- a hydride in reduction to an alcohol

- an amine with formaldehyde and a carbonyl compound in the Mannich reaction

- an enolate ion in an aldol reaction or Baylis–Hillman reaction

- an organometallic nucleophile in the Grignard reaction or the related Barbier reaction or a Reformatskii reaction

- ylides such as a Wittig reagent or the Corey–Chaykovsky reagent or α-silyl carbanions in the Peterson olefination

- a phosphonate carbanion in the Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons reaction

- a pyridine zwitterion in the Hammick reaction

- an acetylide in alkynylation reactions.

- a cyanide ion in cyanohydrin reactions

In many nucleophilic reactions, addition to the carbonyl group is very important. In some cases, the C=O double bond is reduced to a C-O single bond when the nucleophile bonds with carbon. For example, in the cyanohydrin reaction a cyanide ion forms a C-C bond by breaking the carbonyl's double bond to form a cyanohydrin.

Addition to nitriles

With nitrile electrophiles, nucleophilic addition take place by:[1]

- hydrolysis of a nitrile to form an amide or a carboxylic acid

- organozinc nucleophiles in the Blaise reaction

- alcohols in the Pinner reaction.

- the (same) nitrile α-carbon in the Thorpe reaction. The intramolecular version is called the Thorpe–Ziegler reaction.

- Grignard reagents to form imines.[5] The route affords ketones following hydrolysis[6] or primary amines following imine reduction.[7]

Addition to carbon–carbon double bonds

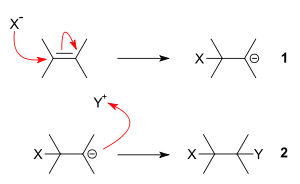

When a nucleophile X− adds to an alkene, the driving force is the transfer of negative charge from X to the electron-poor unsaturated -C=C- system. This occurs through the formation of a covalent bond between X and one carbon atom, concomitant with the transfer of electron density from the pi bond onto the other carbon atom (step 1).[1] During a telescoped second reaction or workup (step 2), the resulting negatively charged carbanion combines with an electrophilic Y to form the second covalent bond.

Unsubstituted and unstrained alkenes are typically insufficiently polar to admit nucleophilic addition, but a few exceptions are known. The most famous is the Varrentrapp reaction, in which a nucleophilic addition "zipper" eventually terminates in decarboxylation. Most nucleophilic addition, however, is to a substituted or strained alkene.

The strain energy in fullerenes weakens their double-bonds; addition thereto is the Bingel reaction.

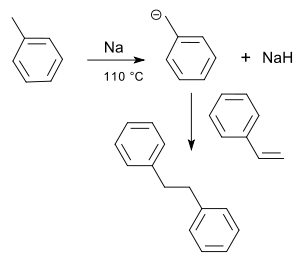

Bonds adjacent to an electron-withdrawing substituent (e.g. a carbonyl group, nitrile, or fluoride) readily admit nucleophilic addition. In this process, conjugate addition, the nucleophile X adds β to the substituent, because then said substituent inductively stabilizes the product's negative charge. Aromatic substituents, although typically electrophilic, can also sometimes stabilize negative charge; for example, styrene reacts in toluene with sodium to give 1,3-diphenylpropane:[8]

Styrene reacts with sodium and toluene to give 1,3-diphenylpropane (one carbon atom omitted)

Styrene reacts with sodium and toluene to give 1,3-diphenylpropane (one carbon atom omitted)

References

- 1 2 3 4 March Jerry; (1985). Advanced Organic Chemistry reactions, mechanisms and structure (3rd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons, inc. ISBN 0-471-85472-7

- ↑ Fleming, Ian (2010). Molecular orbitals and organic chemical reactions. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-74658-5.

- ↑ Bürgi, H. B.; Dunitz, J. D.; Lehn, J. M.; Wipff, G. (1974). "Stereochemistry of reaction paths at carbonyl centres". Tetrahedron. 30 (12): 1563. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90678-7.

- ↑ H. B. Bürgi; J. D. Dunitz; J. M. Lehn; G. Wipff (1974). "Stereochemistry of reaction paths at carbonyl centres". Tetrahedron. 30 (12): 1563–1572. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90678-7.

- ↑ Moureu, Charles; Mignonac, Georges (1920). "Les Cetimines". Annales de chimie et de physique. 9 (13): 322–359. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Moffett, R. B.; Shriner, R. L. (1941). "ω-Methoxyacetophenone". Organic Syntheses. 21: 79. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.021.0079.

- ↑ Weiberth, Franz J.; Hall, Stan S. (1986). "Tandem alkylation-reduction of nitriles. Synthesis of branched primary amines". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 51 (26): 5338–5341. doi:10.1021/jo00376a053.

- ↑ Sodium-catalyzed Side Chain Aralkylation of Alkylbenzenes with Styrene Herman Pines, Dieter Wunderlich J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1958; 80(22)6001–6004. doi:10.1021/ja01555a029