| Type | Beer, lager, porter, cider |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1904 |

| Defunct | 1919 |

| Headquarters | Dawson City, Yukon |

| Owner | Thomas O'Brien |

The O'Brien Brewing and Malting Company, also known as the Klondike Brewery, was a brewery founded by Thomas O'Brien in Klondike City, an adjoining settlement to Dawson City, Yukon Territory, Canada from 1904 to 1919. It was established during a period in which Dawson City was expected to become an important regional city, and used modern techniques and equipment imported from California. It was initially successful, selling 68,748 gallons of beer in 1905, but Dawson's population declined and growing temperance attitudes threatened the business. O'Brien sold the company in 1915, and in 1919 prohibition forced its closure. The brewery was abandoned, and the remains of the site are now owned by the Tr'ondek Hwech'in First Nation.

Background

Dawson City was founded in 1896 in the early days of the Klondike Gold Rush, alongside the Yukon River in north-western Canada.[1] Swelled by would-be gold-miners and adventurers, Dawson's population soared to 30,000 at the height of the rush in 1898.[2] Dawson declined in size again as many of the immigrants left, but it was appointed the Territorial Capital of the new Yukon Territory in 1900, and by the following year it had a stable population of around 10,000.[3]

Imported beer had been very expensive during the initial gold rush, costing around $100 a barrel, or approximately $1 a bottle.[4][lower-alpha 1] The Dawson City Brewery had been established in the city by a businessman called T. Krozner in 1898 to manufacture a local alternative, but this had closed by 1902 as the city's population declined and prices fell.[6]

Thomas O'Brien was a Canadian miner and businessman who had prospered considerably during the rush, investing widely in businesses across the city to become one of the wealthiest of the local hotel and saloon owners.[7] O'Brien had considerable confidence that Dawson would continue to grow as an economic powerhouse in the region, both because of its remaining gold deposits and the presence of Canadian government institutions.[8] O'Brien believed that transportation costs would inevitably keep the prices for imported beer high in Dawson and make a local brewery a profitable venture, with the potential to export its product into the neighbouring U.S. district of Alaska.[9]

Creation

The legal paperwork for the O'Brien Brewing and Malting Company was completed in late 1903 and the company was formally created in February 1904 by O'Brien as the majority shareholder with 77 percent of the stock, and six other investors.[10] The company had an initial capital of $200,000 and owned $53,000 of land in Klondike City, just across the river from Dawson, which O'Brien had sold to the new company.[10][lower-alpha 1] George Mero was employed to build the new brewery at considerable speed - 15 days were allowed for the work's completion - converting O'Brien's old building for its new use.[11] The brewery was situated alongside the Klondike Mines Railway terminal, also owned by O'Brien.[11] It opened for business in April.[11]

O'Brien intended the brewery to be a modern facility similar to those in California, and brought in Charles Bolbrugge, a brewer from San Francisco, to run the operation.[12] The facility probably took the form of a tower brewery, which minimised the requirements for power supplies, and had a cooperage built adjacent to it.[13] Some of the equipment was probably reused from the local Eldorado Bottling works, which had closed three years before, and possibly the old Dawson City Brewery, which was then combined with up-to-date steam pumps, bottling machines and an artificial refrigeration plant.[14] A variety of second-hand bottles were probably collected from around Dawson City, many of which were then reused at the new brewery, the remainder being discarded along the nearby river shore.[15] The malt and hops for the brewing process were imported from California.[16]

A variety of products were manufactured over the lifetime of the brewery, including lager, "Blue Label" and "Special Brew" branded lagers, "Red Label" steam beer, "Bohemiam" bock, porter, "Champagne" cider, ginger beer and various non-alcoholic sodas and drinks.[17] Newspaper reports suggested that between 1,200 and 1,500 gallons of beer could be produced a day and, by September, the brewery's lager was selling at $3.50 for a dozen bottles.[18][lower-alpha 1]

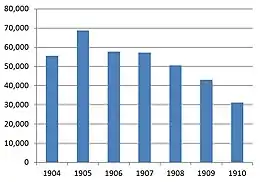

The brewery quickly dominated the local market in its first year of operation, producing 68,748 gallons in 1905 and pushing sales of imported beer down by almost half.[19] O'Brien became the leader of the Yukon Independent Party and held political meetings in the brewery, leading to his faction becoming known as the "steam beers".[20] He used his political connections to support the imposition of a 50 cent per gallon tax on foreign beer in the Yukon in 1907.[21][lower-alpha 1]

Decline

O'Brien's company soon encountered problems. Despite expectations, Dawson City's population began to decline again: one resident, Laura Berton, later described how people were "trickling from it like water from a leaky barrel".[22] By 1909 the population had fallen to 2,000, driving down demand for the brewery's products.[22] Export sales in the highly competitive Alaskan marketplace failed to materialise.[23] The temperance movement also gained ground, almost managing to pass a law introducing prohibition across the territory in 1916. The number of licensed saloons dropped sharply, from 21 in 1902 to only 6 in 1906, and other sales outlets were curtailed.[24] Despite the company's efforts to advertise their product - promoting the health benefits of beer and the company's role in championing a local, pioneering industry - sales dropped considerably after 1908, falling to 31,305 gallons by 1910.[25]

Closure

In 1915, O'Brien, by now in poor health as a consequence of alcohol abuse, sold his shares in the brewery to Joseph Segber, who appointed F. Vinnicomb to manage the company day-to-day.[26] The sale of alcohol in the territory was suspended in the autumn of 1919, full prohibition followed the next year, and the company ceased trading.[26] Initially the premises were kept maintained, probably in case the company was able to reopen, but most of the equipment was sold off to a new brewery in Fairbanks in 1933.[27] The buildings were soon dismantled, probably for firewood, and vegetation reclaimed the site.[28] The rusting brewery steam boiler remained on the site, surrounded by mounds of used bottles, many of which were dug up and removed by collectors over subsequent years, leaving perhaps over 3,000 intact bottles still in place.[29] The remains of a Perfection Bottling Machine and a Crown capping device were left buried beneath the debris.[29]

In 1977 the site was threatened with destruction as part of wider plans to dredge the Klondike City site for gold.[30] The land was instead purchased by the Government of Canada, and the site is now owned by the Tr'ondek Hwech'in First Nation.[30] An archaeological investigation of the site took place in 1998, documenting the structure of the building and analysing the industrial remains.[31]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 During this period, the US and Canadian dollars were both attached to the gold standard and held equal value. For this reason the academic literature and contemporary accounts do not usually differentiate between gold rush prices quoted in US or Canadian dollars. A $1 bottle of beer in 1898 would be equivalent in value to US $29.40 in 2014, using the US Consumer Price Index for comparison. $3.50 for a dozen bottles in 1904 would be the equivalent to US $96 in 2014. A 50 cents tax on a gallon of beer in 1907 would the equivalent to US $13 in 2014. Company equity and property worth $200,000 and $53,000 in 1904 would be the equivalent in value to US $134 million and $35.5 million respectively, using a relative share of GDP index.[5]

References

- ↑ Berton 2001, pp. 47–48

- ↑ Porsild 1998, p. 191

- ↑ Porsild 1998, p. 191; Burley & Will 2000, p. 38

- ↑ Burley & Will 2002, pp. 12–13

- ↑ Lawrence H. Officer; Samuel H. Williamson (2014), "Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount - 1774 to Present", MeasuringWorth, retrieved 5 September 2015

- ↑ Burley & Will 2002, p. 13

- ↑ Burley & Will 2000, p. 38; Porsild 1998, p. 97

- ↑ Burley & Will 2002, pp. 10–11

- ↑ Burley & Will 2000, p. 38; Burley & Will 2002, p. 17

- 1 2 Burley & Will 2000, pp. 38–39; Burley & Will 2002, p. 13

- 1 2 3 Burley & Will 2000, p. 39; Burley & Will 2002, pp. 11, 15, 32

- ↑ Burley & Will 2000, p. 39; Burley & Will 2002, p. 1

- ↑ Burley & Will 2002, pp. 25, 65

- ↑ Burley & Will 2002, pp. 29, 88

- ↑ Burley & Will 2002, p. 79

- ↑ Burley & Will 2002, p. 23

- ↑ Burley & Will 2000, pp. 39–40; Burley & Will 2002, pp. 25–26

- ↑ Burley & Will 2002, pp. 24–25

- ↑ Burley & Will 2000, p. 40

- ↑ Burley & Will 2002, pp. 15–16

- ↑ Burley & Will 2002, p. 16

- 1 2 Berton 1974, p. 119; Burley & Will 2002, p. 16

- ↑ Burley & Will 2002, pp. 17, 19

- ↑ Burley & Will 2002, p. 29

- ↑ Burley & Will 2000, pp. 40–41

- 1 2 Burley & Will 2000, p. 41; Burley & Will 2002, p. 22

- ↑ Burley & Will 2002, pp. 32, 35

- ↑ Burley & Will 2002, pp. 32, 35, 49, 51

- 1 2 Burley & Will 2002, pp. 35, 51, 67

- 1 2 Burley & Will 2002, p. 3

- ↑ Burley & Will 2002, p. 4

Bibliography

- Berton, Laura Beatrice (1974). I Married the Klondike. Toronto, Canada: McClelland and Stewart. ISBN 0-7710-1240-3.

- Berton, Pierre (2001) [1971]. Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush 1896–1899. Toronto, Canada: Anchor Canada. ISBN 0-385-65844-3.

- Burley, David V.; Will, Michael H. (2000). "'The Beer That Made Klondike Famous and Milwaukee Jealous': The O'Brien Brewing and Malting Company Site, Klondike City, Yukon". IA, The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology. 26 (1): 37–54. JSTOR 40968505.

- Burley, David V.; Will, Michael H. (2002). Special Brew: Industrial Archaeology and History of the Klondike Brewery. Dale Eftoda, Minister, US: Heritage Branch, Government of the Yukon.

- Porsild, Charlene (1998). Gamblers and Dreamers: Women, Men, and Community in the Klondike. Vancouver, Canada: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 0-7748-0650-8.