| Jeu de Paume Oath | |

|---|---|

Serment du Jeu de Paume | |

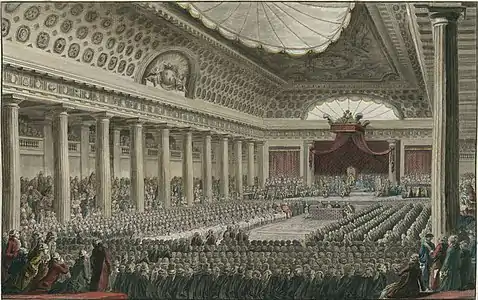

Drawing by Jacques-Louis David of the Tennis Court Oath. David later became a deputy in the National Convention in 1793 | |

| General information | |

| Type | Sport |

| Location | Royal Tennis Court of Versailles |

| Coordinates | 48°48′3.6″N 2°7′26″E / 48.801000°N 2.12389°E |

| Date | June 20, 1789 |

|---|---|

| Cause | Causes of the French Revolution |

| Motive | Creation of a French Constitution |

| Participants | National Assembly |

On 20 June 1789, the members of the French Third Estate took the Jeu de Paume Oath (French: Serment du Jeu de Paume) in the tennis court which had been built in 1686 for the use of the Palace of Versailles.[1] Their vow "not to separate and to reassemble wherever necessary until the Constitution of the kingdom is established" became a pivotal event in the French Revolution.

The Estates-General had been called to address the country's fiscal and agricultural crisis, but they had become bogged down in issues of representation immediately after convening in May 1789, particularly whether they would vote by order or by head (which would increase the power of the Third Estate, as it outnumbered the other two estates by a large margin). On 17 June, the Third Estate began to call itself the National Assembly, led by Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, Comte de Mirabeau.[2]

On the morning of 20 June, the deputies were shocked to discover that the chamber door was locked and guarded by soldiers. They immediately feared the worst and were anxious that a royal attack was imminent from King Louis XVI, so upon the suggestion of one of their members Joseph-Ignace Guillotin,[3] the deputies congregated in a nearby indoor royal tennis court near the Palace of Versailles. The 576 of the 577 members from the Third Estate took the oath[4] – the only person who did not join was Joseph Martin-Dauch from Castelnaudary, who would only execute decisions that were made by the monarch.[5]

Background

Before the Revolution, French society—aside from royalty—was divided into three estates. The First Estate comprised the clergy; the Second Estate was the nobility. The rest of France—some 97 per cent of the population—was the Third Estate, which ranged from very wealthy city merchants to impoverished rural farmers. The three estates had historically met in the Estates General, a legislative assembly, [6] but this had not happened since 1614.

The Estates General of 1789 was a general assembly representing the French estates of the realm: the clergy (First Estate), the Nobility (Second Estate), and the commoners (Third Estate). It was the last of the Estates General of the Kingdom of France. Summoned by King Louis XVI, the Estates General of 1789 ended when the Third Estate formed the National Assembly and, against the wishes of the King, invited the other two estates to join. This signaled the outbreak of the French Revolution.[7]

The Third Estate comprised the overwhelming majority of the French population but the structure of the Estates-General was such that the Third Estate comprised a bare majority of the delegates. A simple majority was sufficient—as long as delegate votes were cast together. The First and Second Estates preferred to divide the vote; a proposal might need to receive approval from each Estate or there might be two "houses" of the Estates-General (one for the first two Estates, and one for the Third) and a bill would need to be passed by both houses. Either way, the First and Second Estates could exercise a veto over proposals enjoying widespread support among the Third Estate, such as reforms that threatened the privileges of the nobility and clergy.

Oath

The deputies' fears, even if wrong, were reasonable and the importance of the oath goes above and beyond its context.[8] The oath was a revolutionary act and an assertion that political authority derived from the people and their representatives rather than from the monarchy. Their solidarity forced Louis XVI to order the clergy and the nobility to join the Third Estate in the National Assembly to give the illusion that he controlled the National Assembly.[2] This oath was vital to the Third Estate as a protest that led to more power in the Estates General, every governing body thereafter.[9]

An English-language translation of the oath reads:

The National Assembly,

Considering that it has been called to establish the constitution of the realm, to bring about the regeneration of public order, and to maintain the true principles of monarchy; nothing may prevent it from continuing its deliberations in any place it is forced to establish itself; and, finally, the National Assembly exists wherever its members are gathered.

Decrees that all members of this Assembly immediately take a solemn oath never to separate, and to reassemble wherever circumstances require until the constitution of the realm is established and fixed upon solid foundations; and that said oath having been sworn, all members and each one individually confirms this unwavering resolution with his signature.

We swear never to separate ourselves from the National Assembly, and to reassemble wherever circumstances require until the constitution of the realm is drawn up and fixed upon solid foundations.[10]

Significance and aftermath

The Oath signified for the first time that French citizens formally stood in opposition to Louis XVI. The National Assembly's refusal to back down forced the king to make concessions. It was foreshadowed by and drew considerably from the 1776 United States Declaration of Independence, especially the preamble. The Oath also inspired a wide variety of revolutionary activities in the months afterwards, ranging from rioting in the French countryside to renewed calls for a written constitution. It reinforced the Assembly's strength, and although the King attempted to thwart its effect, Louis was forced to relent and on 27 June 1789 he formally requested that voting occur based on head counts, not on each estates' power.[11] The Tennis Court Oath (20 June 1789) preceded the abolition of feudalism (4 August 1789) and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (26 August 1789) as the National Assembly became increasingly radical.

Following the 100 year celebration of the oath in 1889, what had been the Royal Tennis Court was again forgotten and deteriorated. Prior to World War II, there was a plan to convert it into a table tennis room for Senate administrators at the Palace. In 1989 the bicentenary of the French Revolution was an opportunity to restore the tennis court.[12]

Gallery

The deputies of the third estate meeting in the tennis court at the Château of Versailles, swearing not to disperse until a constitution is assured.

The deputies of the third estate meeting in the tennis court at the Château of Versailles, swearing not to disperse until a constitution is assured. Etching by Helman after C. Monnet, “Serment du Jeu de Paume à Versailles” on 19 June 1789

Etching by Helman after C. Monnet, “Serment du Jeu de Paume à Versailles” on 19 June 1789 In the western gallery of the Salle du Jeu de Paume, reproductions of the engravings are on display.

In the western gallery of the Salle du Jeu de Paume, reproductions of the engravings are on display.

See also

References

- ↑ "The Royal tennis court". Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- 1 2 Doyle, William (1990). The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0192852212.

- ↑ Donegan, Ciaran F. (1990). "Dr Guillotin – reformer and humanitarian". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 83 (10): 637–639. doi:10.1177/014107689008301014. PMC 1292858. PMID 2286964.

- ↑ Thompson, Marshall Putnam (1914). "The Fifth Musketeer: The Marquis de la Fayette". Proceedings of the Bunker Hill Monument Association at the annual meeting. p. 50. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- ↑ Hanson, Paul R. (2004). Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810850521.

- ↑ Estates-General in Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ "Summoning of the Estates General, 1789". Palace of Versailles. 23 August 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ↑ Osen, James L. (1995). Royalist Political Thought during the French Revolution. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313294419.

- ↑ John D Ruddy (12 January 2015), French Revolution in 9 Minutes, retrieved 29 February 2016

- ↑ "The Tennis Court Oath, June 1789" (PDF). Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ↑ Hanson, Paul R. (2015). Historical dictionary of the French Revolution (Second ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 118. ISBN 9780810878914.

- ↑ "The Royal Tennis Court". Retrieved 21 June 2021.

External links

- Wilde, Robert (2014). "The Estates General and the Revolution of 1789". about.com. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

Works related to Tennis Court Oath at Wikisource

Works related to Tennis Court Oath at Wikisource Media related to Tennis Court Oath at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tennis Court Oath at Wikimedia Commons- Official site of the French Courte Paume Comité (Real tennis in french) (in French)

- Article "Tennis" in the 1797 edition of Encyclopedia Britannica

- The Real Tennis Society

- The Tennis Court Oath by Robinson, James Harvey

- Tennis court Versailles

- The Tennis Court Oatk Author(s): James Harvey Robinson Source: Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 10, No. 3 (Sep., 1895), pp. 460–474 Published by: The Academy of Political Science, Accessed: 01-01-2022 17:18 UTC