| Kalahari Basin | |

|---|---|

| Kalahari Depression | |

| |

| Country | Angola, Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe |

| Cities | Windhoek |

| Characteristics | |

| Area | 725,293 km2 (280,037 sq mi)[1] |

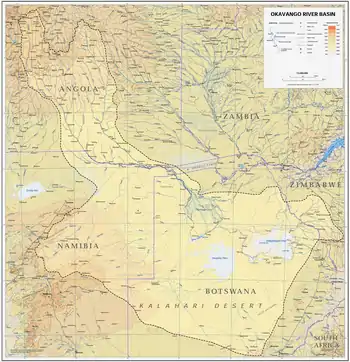

The Kalahari Basin, also known as the Kalahari Depression, Okavango Basin or the Makgadikgadi Basin,[1] is an endorheic basin and large lowland area covering approximately 725,293 km2 - mostly within Botswana and Namibia, but also parts of Angola, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The outstanding physical feature in the basin, and occupying the centre, is the large Kalahari Desert.

The perennial river bifurcation of Selinda Spillway (or Magweggana River), on the Cuando River, connects the Kalahari basin to the Zambezi Basin.[2]

General characteristics of the basin

The Okavango River is the chief stream in the basin. It is formed by the confluence of the Cubango and Cuito rivers, which originate on the Bié Plateau of central Angola and flow southeast. The Cubango is joined just above its confluence with the Cuito by the Omatako River, which flows northeast from its origin in the Damaraland region of central Namibia. The Okavango continues through the Caprivi Strip of Namibia into Botswana, where it splits into a number of distributaries to form the Okavango Delta, a large inland delta that becomes a seasonally flooded grassland. After the Okavango Delta, the waters of the basin enter a zone of strong evaporation, already within the Kalahari Desert depression.[3]

A series of salt pans lie in the lowest points of the basin, including the Nwako Pan south of the Okavango Delta and the vast Makgadikgadi Pan southeast of the Delta. At times of high flow, the Okavango spills into the Nwako Pan via the Xudum and Nhabe distributaries to replenish Lake Ngami, a saline lake, and into Lake Xau and the western end of the Makgadikgadi Pan via the Boteti distributary. The Mopipi Dam was built on the Boteti to provide water to the Orapa diamond mine.[4]

The Selinda Spillway, also known as the Magweqana, Magwekwana or Magweggana, is a distributary channel that connects the Okavango Delta to the Cuando River, a tributary of the Zambezi.[2] In periods of very high water in the Okavango, the water flows eastward towards the Cuando-Linyanti-System. The last time this happened was in August 2009 after 30 years of falling dry. In times of high water in the Kwando, the water can flow west from the Cuando towards the Okavango Delta, but often evaporates before it reaches the delta.[5]

Other streams in the basin include the Eiseb, an intermittent stream that originates in Namibia's Herreroland and flows east into the Okavango Delta, and the Nata River, which originates in western Zimbabwe to flow into the eastern end of the Makgadikgadi Pan.[5]

Ecology

Despite its aridity, the Kalahari Basin supports a variety of fauna and flora on soils known as Kalahari sands. The native flora includes acacia trees, African rosewood and a large number of herbs and grasses.[6] Some of the areas within the Kalahari are seasonal wetlands, such as the Makgadikgadi Pans of Botswana. This area, for example, supports numerous halophilic species and, in the rainy season tens of thousands of flamingos visit these pans.[7]

Water resource management

The source of the Okavango Delta's waters in Angola and Namibia remain unaffected by any upstream dams or significant water abstraction and the three riparian states have established a protocol under the Permanent Okavango River Basin Water Commission (OKACOM) for the sustainable management of the entire river system.[4]

See also

- Nxai Pan

- Nata River

- Tsodilo Hills

- Lake Makgadikgadi - the paleo lake , the largest in Africa, which once occupied the basin until 10 thousand years ago.

References

- 1 2 Ashton, Peter; Neal, Marian (2003). "An overview of key strategic issues in the Okavango basin". In Turton, A.R.; Ashton, P.J.; Cloete, T.E. (eds.). Transboundary Rivers, Sovereignty and Development: Hydropolitical Drivers in the Okavango. pp. 31–63. CiteSeerx: 10.1.1.468.8632.

- 1 2 Is this Harry and Meghan's honeymoon hotel?. The Telegraph. 29 May 2018.

- ↑ Kalahari and Okavango Delta. Earth Observatory - Nasa. 6 August 2008.

- 1 2 Okavango Delta. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2019.

- 1 2 Thomas, David.; Shaw, Paul A.. The Kalahari Environment. Cambridge University Press, 21 February 1991

- ↑ Martin Leipold, 2008]

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan, 2008

Sources

- C. Michael Hogan (2008) Makgadikgadi, Megalithic Portal, ed. A.Burnham

- Martin Leipold (2008) Plants of the Kalahari

- A.J.E. Els and K.M. Rowntree Water Resources in the Savanna Regions of Botswana Geography Department, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa

- Thieme, Michelle L. (2005). Freshwater Ecoregions of Africa and Madagascar: A Conservation Assessment. Island Press, Washington DC.