| Rugby School | |

|---|---|

| |

Rugby School, seen from 'The Close' playing field. | |

| Address | |

Lawrence Sheriff Street , CV22 5EH England | |

| Coordinates | 52°22′03″N 1°15′40″W / 52.3675°N 1.2611°W |

| Information | |

| Type | Public school Private boarding school |

| Motto | Latin: Orando Laborando (by praying, by working) |

| Religious affiliation(s) | Church of England |

| Established | 1567 |

| Founder | Lawrence Sheriff |

| Department for Education URN | 125777 Tables |

| Executive Head Master | Peter Green |

| Head | Gareth Parker-Jones |

| Gender | Co-educational |

| Age | 13 to 18 |

| Enrolment | 810 |

| Houses | 16 |

| Colour(s) | Duck Egg Blue |

| Former pupils | Old Rugbeians |

| School song | Floreat Rugbeia |

| Website | rugbyschool.co.uk |

Rugby School is a public school (English fee-charging boarding school for pupils aged 13–18) in Rugby, Warwickshire, England.[1]

Founded in 1567 as a free grammar school for local boys, it is one of the oldest independent schools in Britain.[2] Up to 1667, the school remained in comparative obscurity. Its re-establishment by Thomas Arnold during his time as Headmaster, from 1828 to 1841, was seen as the forerunner of the Victorian public school.[3] It was one of nine prestigious schools investigated by the Clarendon Commission of 1864 and later regulated as one of the seven schools included in the Public Schools Act 1868. Originally a boys school, it became fully co-educational in 1992.[4]

The school's alumni – or "Old Rugbeians" – include a UK prime minister, several bishops, prominent poets, scientists, writers and soldiers.

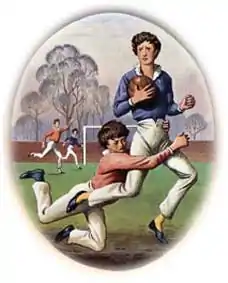

Rugby School is the birthplace of rugby football.[5]

History

Foundation and early growth

Rugby School was founded in 1567 as a provision in the will of Lawrence Sheriff, who had made his fortune supplying groceries to Queen Elizabeth I of England.[6] In the last few months of his life, Sheriff had drawn up a will which stipulated that his fortune should be used to found almshouses and a free grammar school "to serve chiefly for the children of Rugby and Brownsover... and next for such as be of other places hereunto adjoyneing.". Shortly before his death, Sheriff added a codicil to his will reducing the amount of money he left to the school, possibly due to a family financial problem, but instead leaving his eight acre Conduit Close estate in Middlesex: At the time this seemed like a poor exchange, as the estate consisted of undeveloped farmland on the edge of London, however, in time this endowment made Rugby School a wealthy institution due to the subsequent development of the area and rise in land values. The area of what is now the Rugby Estate includes much of what is now Great Ormond Street, Lamb's Conduit Street and Rugby Street in the London district of Bloomsbury.[7]

Up to 1667, the school remained in comparative obscurity. Sheriff's endowment was not fully realized for some time, due to a challenge over the provisions of the will from the Howkins family, to whom Sheriff was related through his sister, Bridget. Its history during that trying period is characterised mainly by a series of lawsuits between the Howkins family, who tried to defeat the intentions of the testator, and the masters and trustees, who tried to carry them out. A final decision was handed down in 1667, confirming the findings of a commission in favour of the trust, and henceforth the school maintained a steady growth.[8] Under the headmastership of Henry Holyoake (from 1688 to 1731) the school became more than simply a local concern, and began to take on national importance.[8] By the end of the 17th century, there were pupils from every part of England attending the school.[9]

The school was originally based in a wooden schoolhouse on Church Street opposite St Andrew's Church, which incorporated Lawrence Sheriff's former house. By the 1740s this building was in poor condition, and the school looked to relocate to new premises. In 1750, the school moved to its current location to the south of the town centre, when it purchased a former Manor House at the south of High Street; this became the Master's house, a new schoolhouse was built alongside. The current school buildings date from the 19th and early 20th centuries.[10]

Henry Ingles, who was Headmaster between 1794 and 1806, was known for his strict discipline and gained the nickname "The Black Tiger". His time as Headmaster is most notable for the 'Great Rebellion' of 1797: It started when Ingles heard one of the boys shoot a cork gun, and the boy told him that Mr Rowell, a grocer, had supplied the gunpowder. Mr Rowell denied this, and as a result the boy Astley was flogged by Ingles, the boys retaliated by smashing Mr Rowell's windows and Ingles insisted that the boys pay for the damage. This provoked a full-scale riot, in which the boys blew off doors, smashed windows and burned furniture and books. As the other Masters were away, Ingles called on help from the townsfolk. A party of recruiting soldiers and some townsfolk advanced on the rioters, who retreated onto a moated island in the school grounds. The Riot Act was read out by a local justice of the peace, calling on the boys to surrender, and while this caused a distraction a group of soldiers waded across the moat from the rear and took the boys prisoner.[10]

Victorian period

Rugby School's most famous headmaster was Thomas Arnold, from 1828 to 1841, whose emphasis on moral and religious principle, was widely admired and was seen as the blueprint for Victorian public schools. Arnold's period as headmaster is immortalised in Thomas Hughes 1857 novel Tom Brown's School Days. In the Victorian period, Rugby School saw several further Headmasters of some distinction, these included Frederick Temple (1858–1869) who would later become the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Percival (1887–1895) after whom the Percival Guildhouse is named, and Herbert Armitage James (1895–1910)[10]

In 1845, a committee of Rugby schoolboys, William Delafield Arnold, W. W. Shirley and Frederick Hutchins,[11] wrote the "Laws of Football as Played At Rugby School", the first published set of laws for any code of football.[11][12]

Rugby was one of the nine prestigious schools investigated by the Clarendon Commission of 1861–64 (the schools under scrutiny being Eton, Charterhouse, Harrow, Shrewsbury, Westminster, and Winchester, and two day schools: St Paul's and Merchant Taylors). Rugby went on to be included in the Public Schools Act 1868, which ultimately related only to the seven boarding schools.

From the early days of the school the pupils were divided into "Foundationers" i.e. boys who lived in Rugby and surrounding villages who received free schooling, as per Sheriff's original bequest, and "Non-Foundationers", boys from outside the Rugby area who paid fees and were boarders. Non-Foundationers were admitted from the early history of the school as they helped to pay the bills. Gradually, as the school's reputation grew, fee-paying Non-Foundationers became dominant and local boys benefited less and less from Sheriff's original intentions. By the latter half of the 19th century it was no longer desirable to have local boys attending a prestigious public school and so a new school – Lawrence Sheriff Grammar School – was founded in 1878 in order to continue Sheriff's original bequest for a free school for local boys.[10]

On several occasions in the late 19th century Rugby School was visited by the French educator Pierre de Coubertin, who would later cite the school as one of the main inspirations for his most notable achievement, the founding of the modern Olympic Games in 1896.[13][14]

Modern history

_3.23.jpg.webp)

In 1975 two girls were admitted to the sixth form and the first girls' house opened three years later, followed by three more. In 1992 the school became fully co-educational when the first 13-year-old girls arrived, and in 1995 Rugby had its first-ever Head Girl, Louise Woolcock, who appeared on the front page of The Times. In September 2003 the last girls' house was added. Today, total enrolment of day pupils, from forms 4 to 12, numbers around 800.[15]

Rugby football

The game of Rugby football owes its name to the school.

The legend of William Webb Ellis and the origin of the game is commemorated by a plaque. The story is that Webb Ellis was the first to pick up a football and run with it, and thus invent a new sport. However, the sole source of the story is Matthew Bloxam, a former pupil but not a contemporary of Webb Ellis. In October 1876, four years after the death of Webb Ellis, in a letter to the school newspaper The Meteor he quotes an unknown friend relating the story to him. He elaborated on the story four years later in another letter to The Meteor, but shed no further light on its source. Richard Lindon, a boot and shoemaker who had premises across the street from the school's main entrance in Lawrence Sheriff Street, is credited with the invention of the "oval" rugby ball, the rubber inflatable bladder and the brass hand pump.[16]

There were no standard rules for football in Webb Ellis's time at Rugby (1816–1825) and most varieties involved carrying the ball. The games played at Rugby were organised by the pupils and not the masters, the rules being a matter of custom and not written down. They were frequently changed and modified with each new intake of students.

Rugby fives

Rugby fives is a handball game, similar to squash, played in an enclosed court. It has similarities with Winchester fives (a form of Wessex fives) and Eton fives.

It is most commonly believed to be derived from Wessex fives, a game played by Thomas Arnold, Headmaster of Rugby, who had played Wessex fives when a boy at Lord Weymouth's Grammar, now Warminster School. The open court of Wessex fives, built in 1787, is still in existence at Warminster School although it has fallen out of regular use.

Rugby fives is played between two players (singles) or between two teams of two players each (doubles), the aim being to hit the ball above a 'bar' across the front wall in such a way that the opposition cannot return it before a second bounce. The ball is slightly larger than a golf ball, leather-coated and hard. Players wear leather padded gloves on both hands, with which they hit the ball.

Rugby fives continues to have a good following with tournaments being run nationwide, presided over by the Rugby Fives Association.[17]

Cricket

The school has produced a number of cricketers who have gone onto play Test and first-class cricket. The school has played host to two major matches, the first of which was a Twenty20 match between Warwickshire and Glamorgan in the 2013 Friends Life t20.[18] The second match was a List-A one-day match between Warwickshire and Sussex in the 2015 Royal London One-Day Cup, though it was due to host a match in the 2014 competition, however this was abandoned.[19] In the 2015 match, William Porterfield scored a century, with a score of exactly 100.[20]

Houses

Rugby School has both day and boarding-pupils, the latter in the majority. Originally it was for boys only, but girls have been admitted to the sixth form since 1975. It went fully co-educational in 1992. The school community is divided into houses.

| House | Founded † | Girls/Boys |

|---|---|---|

| Cotton | 1836[21] | Boys |

| Kilbracken | 1841[22] | Boys |

| Michell | 1882[23] | Boys |

| School Field | 1852[24] | Boys |

| School House | 1750[25] | Boys |

| Sheriff | 1930[26] | Boys |

| Town House | 1567[27] | Boys (Day) |

| Whitelaw | c.1790[28] | Boys |

| Bradley | 1830 (1992)[29] | Girls |

| Dean | 1832 (1978)[30] | Girls |

| Griffin | 2003[31] | Girls |

| Rupert Brooke | 1860 (1988)[32] | Girls |

| Southfield | 1993[33] | Girls (Day) |

| Stanley | 1828 (1992)[34] | Girls |

| Tudor | 1893 (2002)[35] | Girls |

- † Numbers in brackets indicate date of conversion to a Girls' house where applicable

Academic life

Pupils beginning Rugby in the F Block (first year) study various subjects.[36] In a pupil's second year (E block), they do nine subjects which are for their GCSEs, this is the same for the D Block (GCSE year).[37] The school then provides standard A-levels in 29 subjects. Students at this stage have the choice of taking three or four subjects and are also offered the opportunity to take an extended project. The School also offers taking the IB Diploma Programme.[38] Oxbridge acceptance percentage in 2007 was 10.4% [39]

Scholarships

The Governing Body provides financial benefits with school fees to families unable to afford them. Parents of pupils who are given a Scholarship are capable of obtaining a 10% fee deduction, although more than one scholarship can be awarded to one student.

Fees

Former pupils

There have been a number of notable Old Rugbeians, including the purported father of the sport of Rugby William Webb Ellis, the inventor of Australian rules football, Tom Wills, the war poets Rupert Brooke and John Gillespie Magee, Jr., Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, author and mathematician Lewis Carroll, poet and cultural critic Matthew Arnold, the author and social critic Salman Rushdie (who said of his time there: "Almost the only thing I am proud of about going to Rugby school was that Lewis Carroll went there too."[41]) and the Irish writer and republican Francis Stuart. The Indian concert pianist, music composer and singer Adnan Sami also studied at Rugby School.[42] Matthew Arnold's father Thomas Arnold, was a headmaster of the school. Philip Henry Bahr (later Sir Philip Henry Manson-Bahr), a zoologist and medical doctor, World War I veteran, was President of both Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene and Medical Society of London, and vice-president of the British Ornithologists' Union.[43][44] Richard Barrett Talbot Kelly joined the army in 1915, straight after leaving the school, earned a Military Cross during the First World War, and later returned to the school as Director of Art.[45]

Rugbeian Society

The Rugbeian Society is for former pupils at the school.[46] An Old Rugbeian is sometimes referred to as an OR.

The purposes of the society are to encourage and help Rugbeians in interacting with each other and to strengthen the ties between ORs and the school.

In 2010 the Rugbeians reached the semi-finals of the Public Schools' Old Boys' Sevens tournament, hosted by the Old Silhillians to celebrate the 450th anniversary of fellow Warwickshire public school, Solihull School.

Buildings and architecture

The buildings of Rugby School date from the 18th and 19th century with some early 20th-century additions. The oldest buildings are the Old Quad Buildings and the School House the oldest parts of which date from 1748, but were mostly built between 1809 and 1813, designed by Henry Hakewill, these are grade II* listed.[47][48]

Most of the current landmark buildings date from the Victorian era and were designed by William Butterfield: The most notable of these is the chapel, dating from 1872, which is topped by an octagonal tower 138 feet (42 m) tall, and is grade I listed.[49][50] Butterfield's New Quad buildings are Grade II* listed and date from 1867 to 1885. The Grade II* War Memorial chapel, designed by Sir Charles Nicholson, dates to 1922.[51][52] Nicholson was educated at the school from the late-1870s.[53]

The Temple Speech Room on Barby Road was named after former Rugby headmaster, Frederick Temple,[54] It was opened on 3 July 1909 by King Edward VII.[55] Designed by Thomas Graham Jackson, it is grade II listed.[56] The Macready Theatre is based in a prominent Victorian building on Lawrence Sheriff Street which was built as classrooms in 1885, in 1975 it was converted into a theatre, in 2018, it was opened to the general public.[57]

The School House, of 1813

The School House, of 1813 Old Quad Buildings of 1809-13

Old Quad Buildings of 1809-13.JPG.webp) From left to right; New Quad Buildings, Chapel and War Memorial Chapel.

From left to right; New Quad Buildings, Chapel and War Memorial Chapel. Temple Speech Room

Temple Speech Room

Head Masters

- Richard Seele – 1600

- Nicolas Greenhill – 1602

- Augustus Rolfe – 1606

- Wiligent Greene – to 1642

- Raphael Pearce – 1642 to 1651

- Peter Whitehead

- John Allen – to 1669

- Knightley Harrison – 1669 to 1674

- Robert Aahbridge – 1674 to 1681

- Leonard Jeacocks – 1681 to 1687

- Henry Holyoake – 1687 to 1730

- John Plomer – 1731 to 1742

- Thomas Crossfield – 1742 to 1744

- William Knail – 1744 to 1751

- John Richmond – 1751 to 1755

- Stanley Burrough – 1755 to 1778

- Thomas James – 1778 to 1794

- Henry Ingles – 1794 to 1806

- John Wooll – 1806 to 1827

- Thomas Arnold – 1828 to 1842

- Archibald Campbell Tait – 1842 to 1848

- Meyrick Goulburn – 1849 to 1857

- Frederick Temple – 1858 to 1869

- Henry Hayman – 1870 to 1874

- Thomas William Jex-Blake – 1874 to 1887

- John Percival – 1887 to 1895

- Herbert Armitage James – 1895 to 1910[58]

- Albert Augustus David – 1910 to 1921[58]

- William Wyamar Vaughan – 1921 to 1931[58]

- Percy Hugh Beverley Lyon – 1931 to 1948[58]

- Arthur Frederic Brownlow fforde – 1948 to 1957[58]

- Walter Hamilton – 1957 to 1966[58]

- James Woodhouse – 1967 to 1980

- Brian Rees −1980 to 1985[59]

- Richard Bull – 1985 to 1990[59]

- Michael Mavor – 1990 to 2001[59]

- Patrick Derham – 2001 to 2014[60]

- Peter Green 2014 – 2020 [61]

- Peter Green (Executive Head Master) 2020–

- Gareth Parker Jones (Head) 2020– [62]

Thomas Arnold

Rugby's most famous headmaster was Thomas Arnold, appointed in 1828; he executed many reforms to the school curriculum and administration. Arnold's and the school's reputations were immortalised through Thomas Hughes' book Tom Brown's School Days.

David Newsome writes about the new educational methods employed by Arnold in his book, 'Godliness and Good Learning' (Cassell 1961). He calls the morality practised at Arnold's school muscular Christianity. Arnold had three principles: religious and moral principle, gentlemanly conduct and academic performance. George Mosse, former professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, lectured on Arnold's time at Rugby. According to Mosse, Thomas Arnold created an institution which fused religious and moral principles, gentlemanly conduct, and learning based on self-discipline. These morals were socially enforced through the "Gospel of work". The object of education was to produce "the Christian gentleman," a man with good outward appearance, playful but earnest, industrious, manly, honest, virginal pure, innocent, and responsible.

John Percival

In 1888 the appointment of Marie Bethell Beauclerc by Percival was the first appointment of a female teacher in an English boys' public school and the first time shorthand had been taught in any such school. The shorthand course was popular with one hundred boys in the classes.

Controversy

In September 2005, the school was one of fifty independent schools operating independent school fee-fixing, in breach of the Competition Act, 1998. All of the schools involved were ordered to abandon this practice, pay a nominal penalty of £10,000 each and to make ex-gratia payments totalling three million pounds into a trust designed to benefit pupils who attended the schools during the period in respect of which fee information had been shared.[63][64]

However, the head of the Independent Schools Council declared that independent schools had always been exempt from anti-cartel rules applied to business, were following a long-established procedure in sharing the information with each other and that they were unaware of the change to the law (on which they had not been consulted). She wrote to John Vickers, the OFT director-general, stating "They are not a group of businessmen meeting behind closed doors to fix the price of their products to the disadvantage of the consumer. They are schools that have quite openly continued to follow a long-established practice because they were unaware that the law had changed."[65]

See also

References

- ↑ Simpson, John Barclay Hope (6 February 1967). "Rugby Since Arnold: A History of Rugby School from 1842". Macmillan. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 6 February 2023 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Gabbitas". Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "The truth about Flashman: an old Rugbeian writes". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "Rugby pupils long to keep old-fashioned skirts". The Times. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ↑ "Six ways the town of Rugby helped change the world" Archived 4 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ↑ Rugby by Henry Christopher Bradby

- ↑ "About the Rugby Estate". University College London. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- 1 2 . New International Encyclopedia. Vol. XVII. 1905.

- ↑ Waite, Rev W.O. (1893). "RUGBY: PAST & PRESENT, WITH AN HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF NEIGHBOURING PARISHES". p. 76. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Osbourne, Andy; Rawlins, Eddy (1988). Rugby: Growth of a Town.

- 1 2 Curry, Graham (2001). Football: A Study in Diffusion (PDF). Leicester: University of Leicester. p. 28. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ↑ – via Wikisource.

- ↑ "Rugby school inspired founder of modern Games". Reuters. 18 April 2012. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ↑ "Rugby School welcomes the Olympic Torch". ITV. 2 July 2012. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ↑ University of Oxford student. "Rugby School". Archived from the original on 20 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "richardlindon.com". Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "Welcome". Rugby Fives Association. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ "Twenty20 Matches played on Rugby School Ground, Rugby". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ↑ "List A Matches played on Rugby School Ground, Rugby". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ↑ "Rugby School Ground, Rugby - Centuries in List A matches". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ↑ "Rugby School – Cotton". Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "Rugby School – Kilbracken". Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "Walter Gorden Michell Biography". Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "Rugby – School Field". Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "Rugby School – School House". Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "Rugby School – Sheriff". Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "Rugby School – Town House". Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "Rugby School Register, 1675–1842". Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021. The Rugby School Register records on pp. xxii–xxiii that Whitelaw House, then run by Christopher Moor was in existence about 1790. The first boy to board out with Christopher Moor was Edward Watkin in 1796. The Moors opened the present House on its Hillmorton Road site in 1811.

- ↑ "Rugby School – Bradley". Archived from the original on 25 December 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "The History of Dean House". Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "The History of Griffin House". Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "Rugby School – Rupert Brooke". Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "Rugby School – Southfield (Day)". Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "Rugby School – Stanley". Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "Rugby School – Tudor". Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ↑ "F Block Curriculum Guide" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ↑ "E and D Block Curriculum Guide" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ↑ "Upper School Curriculum Guide" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ↑ http://image.guardian.co.uk/sys-files/Education/documents/2007/09/20/100topoxbridge.pdf Archived 19 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 "Tatler fees guide". Tatler. 16 October 2020. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ↑ Salman Rushdie: The Arab spring is a demand for desires and rights that are common to all human beings Archived 1 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Daily Telegraph

- ↑ "Adnan Sami". India.com. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ↑ "Sir Philip Henry Manson-Bahr". Lives of the fellows : Munk's Roll : Volume VI. Royal College of Physicians of London. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ↑ "Obituary Notices: Sir Philip Manson-Bahr, C.M.G., D.S.O., M.A., M.D., F.R.C.P., D.T.M.&H". British Medical Journal. 2 (5525): 1332–1334. 1966. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5525.1332. PMC 1944321. PMID 5332525.

- ↑ "Lieutenant Richard Talbot Kelly". National Army Museum, London. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ↑ "Rugby School – (Development Office)". Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ Historic England. "OLD QUAD BUILDINGS AT RUGBY SCHOOL (1035021)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ↑ Historic England. "SCHOOL HOUSE AT RUGBY SCHOOL (1183930)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ↑ Historic England. "CHAPEL AT RUGBY SCHOOL (1183714)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ Pernell, Sarah (2006). Rugby. ISBN 1-85937-620-7.

- ↑ Historic England. "NEW QUAD BUILDINGS AT RUGBY SCHOOL (1035020)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ↑ Historic England. "WAR MEMORIAL CHAPEL AT RUGBY SCHOOL (1365005)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ↑ Historic England. "Tombstone of Sir Charles Nicholson and family (1472162)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ↑ "A brief history of Rugby School, Flourishing in the 20th Century". Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ↑ "Rugby School. Temple Speech Room, Opening". Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ↑ "Temple Speech Room at Rugby School A Grade II Listed Building in Rugby, Warwickshire". British Listed Buildings. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ↑ "First professional theatre in Rugby to open next week". Rugby Observer. 28 November 2018. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 John Barclay Hope Simpson, Rugby Since Arnold: A History of Rugby School from 1842, Published by Macmillan, 1967

- 1 2 3 "Rugby School – Home". rugbyschool.co.uk. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ↑ "New Post for Head Master". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "New Head Master Announced". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "Rugby School - Rugby School Senior Management Team". Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ Halpin, Halpin. "Independent schools face huge fines over cartel to fix fees". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ↑ "Office of Fair Trading Press Release". National Ara chive. 21 December 2006. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ↑ "Private schools send papers to fee-fixing inquiry". The Daily Telegraph. London. 3 January 2004. Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

Further reading

- Carter, George David. "The extent to which the novel" Tom Brown's Schooldays",(1857), by Thomas Hughes, accurately reflects the ideas, purposes and policies of Dr. Thomas Arnold in Rugby School, 1828–1842." (MA thesis, Kansas State U, 1967). online

- Hope-Simpson, John Barclay. Rugby Since Arnold: A History of Rugby School from 1842. (1967).

- Mack, Edward Clarence. Public schools and British opinion, 1780 to 1860: An examination of the relationship between contemporary ideas and the evolution of an English institution (1938), comparison with other elite schools

- Neddam*, Fabrice. "Constructing masculinities under Thomas Arnold of Rugby (1828–1842): gender, educational policy and school life in an early‐Victorian public school." Gender and Education 16.3 (2004): 303–326.

- Rouse, W.H.D. A history of Rugby School (1898) online.