Old St. Andrew's Parish Church | |

Old St. Andrew's in 2021 | |

| |

| Nearest city | Charleston, South Carolina |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 32°50′18″N 80°2′59″W / 32.83833°N 80.04972°W |

| Area | 12.9 acres (5.2 ha) |

| Built | 1706 |

| Architectural style | Colonial |

| NRHP reference No. | 73001694[1] |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1973 |

.jpg.webp)

.tiff.jpg.webp)

Saint Andrew's Parish Church is located in Charleston, South Carolina, along the west side of the Ashley River. Built in 1706 it is the oldest surviving church building south of Virginia.[2] Its historic graveyard dates from the church's establishment.[3] Expanded in 1723 into the shape of a cross, the church is the only remaining colonial cruciform church in South Carolina.[4][5] In 1973 it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.[6] Old St. Andrew's, as it is commonly called, remains an active place of worship and is affiliated with the Anglican Diocese of South Carolina and the Anglican Church in North America.[7]

18th Century: Colonial Era through the American Revolution

Establishment

The Church Act of 1706 established the Church of England as the official state supported religion in the Carolina colony, created the parish system, with both secular and ecclesiastical functions, named ten parishes within the boundaries of the three existing counties (Craven, Berkeley, and Colleton), and designated ten Anglican churches to serve the inhabitants of these parishes. St. Andrew's Parish Church was named to serve residents along the Ashley River.[8][9]

St. Andrew's Parish was approximately 280 square miles: 40 miles north-to-south and 7 miles east-to-west. It was bordered on the south by Folly Island and the Atlantic Ocean, to the east by St. James Goose Creek Parish (through the middle of today's Charleston International Airport), to the west by Rantowles Creek and St. Paul's Parish, and to the north into today's Dorchester County. The area where the English settlers first landed in 1680, today called Charles Towne Landing State Historic Site, is located in St. Andrew's Parish.[10][11]

Residents in the northern part of the parish soon found it too difficult to travel to other parts of the parish, so in 1717 the parish was cut in half. The northern half became the parish of St. George's, Dorchester, with its southern boundary about a mile south of Middleton Place.[12][13] The new St. Andrew's Parish consisted of today's West Ashley and James Island and operated as a governmental jurisdiction until 1865 when it became part of the Charleston District.[14]

The Early Church

St. Andrew's Parish Church was built in 1706. It was forty feet long and twenty-five feet wide, built of brick, with a roof of pine, and had two doors and five small, square windows. A wider "great" door was used by the gentry and faced the river. A narrower "small" door was used by commoners and clergy and faced west. It is likely that enslaved Africans built the church. A graveyard of seven acres surrounded the church.[15]

The first rector was Rev. Alexander Wood. He arrived in 1708 and died two years later.[16] He was succeeded by Rev. Ebenezer Taylor (1712–17), whose tenure was marked by turmoil among his churchwardens, vestry, and parishioners. Taylor was a moderate Presbyterian minister who was recruited by Rev. Gideon Johnston, the Anglican commissary (the Bishop of London's personal representative), to become an ordained Anglican minister. Johnston presented Taylor to the vestry of St. Andrew's Parish Church as Wood's successor. His idea was that Taylor could siphon off Presbyterians to the Church of England in this majority Presbyterian parish. The vestry reluctantly accepted him as rector.[17]

Taylor did not lure Presbyterians to the Anglican fold. In fact, his stubborn personality and unfamiliarity with Anglican customs alienated the very Anglicans he was called to serve. His work among the enslaved on parish plantations, a ministry which few ministers undertook at the time, was another sore point.[18] During his tenure, Indian raids during the Yamasee War occurred almost as far as the Ashley River.[19] In long letters to London, Taylor complained bitterly of the treatment he received from his parishioners.[20][21][22][23] Toward the end of his tenure the churchwardens and vestry nailed the church windows shut and locked the door to prevent him from entering the church and conducting worship services.[24] In 1717 Taylor was banished to North Carolina, where he died three years later.[25]

Stability and Expansion

Rev. William Guy succeeded Ebenezer Taylor in 1718, serving until his death in 1750. His thirty-two-year tenure was one of the longest in the church's history and was even more remarkable in an age where frequent clergy turnover from illness, death, or transfer was the norm.[26] If Ebenezer Taylor was disliked by his parish, William Guy was beloved.[27]

Reverend Guy chronicled parish life in the many letters he sent to the SPG.[28][29][30][31][32][33] He began the parish's first register, the official repository of births, baptisms, marriages, and deaths, when churches and not government agencies maintained vital statistics.[34][35] He established a chapel on James Island to make it easier for parishioners to worship closer to home.[36] He was, however, unsuccessful in ministering to the enslaved on parish plantations.[37]

The parish's twenty-six-acre glebe, where the minister lived and raised crops and livestock, was one of the smallest of all South Carolina parishes.[38] During Guy's tenure it was expanded to eighty-three acres.[39] In 1750 a small, wooden parsonage badly in need of repair was replaced with a spacious, two-story brick house.[39]

As more people settled the Ashley River area, the 1706 church became too small to accommodate even half of those who wanted to worship there.[40][41] Beginning in 1723 and continuing for more than a decade, the small, rectangular church was expanded into the shape of a cross. The expansion tripled the floor space of the existing church. Features of the 1723 expansion that visitors see today include the chancel and transept at the east end, compass-headed windows recessed into the walls, the barrel-vaulted ceiling over the crossing of the aisles, and three equal-size doors. The pine roof was replaced by one of cypress. Cedar pews were added. The exterior brick was roughcast or stuccoed to mask the differences between the old and new brick and emulate a grander stone facade. A steeple at the west end was planned but whether it was ever realized is unknown.[42] Although Anglican churches were supported by public taxes, these were never enough. The expansion required several subscriptions by parishioners to pay for the project.[43] The finished church conveyed a simple elegance or "a quaint severity combined with great charm".[44] The expanded St. Andrew's "reflected many of the essential design features that characterized eighteenth-century church architecture in South Carolina."[45]

Prosperity

The flourishing condition of St. Andrew's Parish Church was the result of a booming economy, primarily the cultivation of rice.[46] None of this prosperity would have been possible without the slave labor system the British imported from Barbados and the West Indies.[47] As early as 1705 there were about 130 white families along the Ashley River and 150 enslaved people.[48] In 1728 Reverend Guy estimated that there were 800 free whites and 1,800 enslaved blacks in the parish.[49]

William Guy was succeeded by Rev. Charles Martyn in 1752.[50] He also had a long tenure, resigning in 1770 to return to England due to ill health.[51] The parish's prosperity continued under his tenure with the addition of a second significant cash crop. The cultivation of indigo was perfected by Eliza Lucas Pinckney at her father's plantation on Wappoo Creek in St. Andrew's Parish.[52][53] The combination of rice and indigo made the parish one of the wealthiest areas in all of colonial British North America.[54][55] More enslaved labor was needed to fuel this engine, and by 1777 the parish's enslaved population reached 3,460.[56][57]

Fire and Rebuilding

In the midst of this prosperity, a devastating fire struck the church in the early 1760s. It was severe enough that anything made of wood would have burned, leaving the 1706 and 1723 walls standing.[58] The church was thoroughly restored and reopened in 1764.[59] The work was funded by parishioner pew subscriptions.[60][61]

Features of the 1764 rebuilding include the magnificent reredos or altarpiece at the east end, the balcony at the west end, the stone and tile paver floor throughout the church, and the red-and-tan tile floor beneath the altar.[62] The large east-end window behind the altar was not replaced after the fire, and the wall bricked in and reredos added. Its four tablets depict the Lord's Prayer, Ten Commandments, and Apostles' Creed. Such an expensive adornment in a simple country church was an expensive undertaking that only a wealthy parish could afford.[63] A balcony which had originally been installed in 1754[64][65] was rebuilt after the fire for people who could not afford to buy their seating.[66] The stone and tile paver floor would be removed in 1855, buried under a new stone floor, and not resurface until 1969.[67] The red-and-tan tile floor in the altar area is possibly of Dutch origin.[68]

American Revolution

After Charles Martyn left for England, he was succeeded by Rev. Thomas Panting (1770–71)[69] and Rev. Christopher Ernst Schwab (1771–73), a Bavarian from Franconia.[70] It would be fourteen years until Schwab was replaced, after the American Revolution.[71]

The Revolution affected the church, parsonage, and chapel on James Island. In March 1780 British and Hessian troops were met with colonial cannon fire at Church Creek, just south of the parish church. British General Alexander Leslie directed Hessian Captain Johann Ewald to take a detachment of men across the creek and silence the rebels. Otherwise, cannon would be brought up which might have destroyed the church. Ewald and his men became mired in the mud, which gave the colonials time to escape. The British and Hessians camped in the churchyard overnight.[72][73] They later proceeded north to Drayton Hall and Magnolia Gardens, where they crossed the Ashley River, marched down the peninsula and captured the city of Charles Town.[74][75] The war left a bitter legacy in St. Andrew's Parish. The parish church was "much Injured and pulled to pieces by the British Army,"[76][77] the parsonage was burned,[76][77] and the chapel on James Island destroyed.[77][78]

19th Century: Antebellum Era, Civil War, and Its Aftermath

Stagnation and Economic Decline

Parishioners set about to restore their church, rebuild the parsonage, and hire a rector. In 1785 the new state House and Senate incorporated the Vestries and Churchwardens of the Parish of St. Andrew and gave them authority over a wide range of issues affecting the parish.[79] A new rector was hired in 1787, the last from England. Rev. Thomas Mills had sailed to Charleston, fleeing his homeland after his staunch support of American independence left him with little opportunity there.[71] His twenty-nine-year tenure (1787-1816) was the only stability in parish leadership until the 1840s.[80]

Prewar prosperity was followed by economic stagnation, with a significant decline in rice cultivation and low-quality indigo becoming noncompetitive in world markets. St. Andrew's, as with other rural parishes, continued to heavily rely on African American slave labor, with 90 percent of the population enslaved.[81] As one observer noted in the 1840s, "for a long time the Ashley river plantations were the most highly appreciated & productive lands in the colony. Now these lands are almost left untilled.... & the whole presents a melancholy sense of abandonment, desolation, & ruin."[82]

St. Andrew's was without another regular minister for eleven of the next thirteen years.[83] The church building was used as a polling place until the 1830s.[84] Rev. Joseph Gilbert was elected rector in 1824 but died the same year.[85] He was followed by Rev. Paul Trapier (1829–35), whose privileged city upbringing made it difficult to adapt to this difficult, rural posting,[86] and Rev. Dr. Jasper Adams (1835–38), former president of the College of Charleston, who likely used his time at St. Andrew's to complete his only book, Elements of Moral Philosophy.[87] The chapel on James Island became its own church, St. James, in 1831.[78][88] In the first half of the century, a white marble tablet memorializing Jonathan Fitch (J. F.) and Thomas Rose (T. R.), the 1706 church building supervisors, was placed over the south exterior door.[89][90]

Antebellum Ministry to the Enslaved

Rev. James Stuart Hanckel served St. Andrew's as deacon and priest from 1838 until 1851.[91] He ministered to his small, white congregation in the parish church during the cooler months (November through May), when the threat of disease was less.[92] Needed church repairs were completed in 1840,[92][93] a baptismal font was installed in 1842 (the same one in use today),[94][95] and the first confirmation class was held in 1843.[95][96]

Soon after he arrived, Hanckel began a regular ministry to the enslaved, the first focused attempt at St. Andrew's to reach out to African Americans on parish plantations.[92] The antebellum parish register, begun by Paul Trapier in 1830, included many slave baptisms, confirmations, marriages, and burials during Hanckel's tenure.[97] Three plantation chapels were constructed for religious instruction and worship. Two were built in 1845: Middleton Chapel in the southern part of the parish on Nathaniel Russell Middleton's plantation and Magwood's Chapel in the center of the parish on Simon J. Magwood's plantation.[98] To the north, John Grimké Drayton, a candidate for Holy Orders, added Magnolia Chapel at his plantation Magnolia-on-the-Ashley in 1850.[99] By the end of Hanckel's tenure, there were twice as many black communicants in the parish as white.[100]

John Grimké Drayton succeeded Stuart Hanckel in late 1851.[101] Drayton, a wealthy plantation owner, renowned horticulturalist, and dedicated Episcopal priest, served St. Andrew's for forty years (1851–91), the longest tenure in the church's history.[101] He witnessed the last of the antebellum years, the Civil War and its devastation, and slow recovery. He continued ministering to the enslaved and took what Stuart Hanckel had begun to new levels. From 1851 to 1859 black communicants outnumbered whites five-to-one.[102]

1855 Restoration

Early in Drayton's tenure the parish church had fallen into a "very dilapidated" state.[103] In 1855 it was thoroughly restored under the leadership of Col. William Izard Bull of Ashley Hall plantation. Much of the look of today's church dates from Bull's restoration. The colonial high-backed pews had deteriorated past the point of saving, so Bull installed more fashionable low-backed pews, each with a latching door. He inscribed his pew plan in the plaster on the north wall of the nave. It was covered up and not discovered until almost a century later. The pulpit and reading desk were moved to their current location. Cast iron railings were installed around the pulpit, desk, and altar, likely to match the look of the font's pedestal. The stone and tile floor was replaced with large, square sandstone pavers, with the earlier flooring buried in the dirt underneath. Bull placed memorial tablets to his ancestors, the Izards and Bulls, on the southeast wall of the chancel. Scenery and cherubs which had been previously painted on the walls, "all to the horror of grandma and the other ladies", were removed.[104]

Civil War

Reverend Drayton remained in the parish during the Civil War.[105] He also served St. John in the Wilderness Church in Flat Rock, North Carolina, as rector during the summer.[106] He gave his last worship service at St. Andrew's on February 12, 1865, before he left for Flat Rock.[105] Confederate forces had surrendered and had left the city and its environs unprotected from invading Union troops and freed slaves who accompanied them.[105]

Drayton returned from Flat Rock to find his home at Magnolia burned but his magnificent gardens spared.[107] He took residence at the Grimké family home on the peninsula in Charleston.[108] (John was born a Grimké but had changed his surname to Drayton in 1836 so that he could inherit Magnolia.)[109] Union forces appropriated St. Andrew's Parish Church as a public meeting and polling place.[110] Drayton could not gain access to his own church.[110]

A postwar report on the condition of St. Andrew's Parish painted a grim picture. The church had survived "but in the midst of a desert. Every residence but one [Drayton Hall], on the west bank of Ashley River was burnt simultaneously with the evacuation of Charleston, by the besieging forces of James Island."[111][112] The observer continued: "The demon of civil war was let loose on this Parish. But three residences exist between the Ashley and Stono rivers [about 8-10 miles from the parish church].... It must be many years before the congregation can return in sufficient numbers to rebuild their homes and restore the worship of God."[111][112]

Postwar Ministry to the Freedmen

After the war the now freed black people abandoned their previously white church connections in "a black exodus of Biblical proportions."[113] Nowhere in South Carolina did the freedmen reunite with their white prewar minister, except with Rev. John Grimké Drayton in St. Andrew's Parish.[114] Walking through the parish in 1867 he met a group of freedmen who asked him to restart religious services.[114][115] This seemingly benign request was in fact monumental.[114]

Drayton began meeting with his black congregants at the three plantation chapels.[116] He preached to "overflowing congregations"[117] and conducted worship on the first, third, and fifth Sundays from November through May.[116] White congregants were almost nonexistent.[116] In 1875 Drayton wrote "the interest of my people has not flagged, and, with great distances to overcome, they have continued 'the assembling of themselves together.'"[118] During this time Drayton, now in his sixties and living with tuberculosis, was walking sixteen-to-eighteen miles from his home in Charleston to the chapels on Sunday, "eating my dinner from my pocket".[116] By 1880 there were only 617 black Episcopalians in the state, and the St. Andrew's chapels were only one of three congregations with any sizeable black membership.[119][120] Black communicants in St. Andrew's Parish now outnumbered whites eight-to-one.[119]

Church Reopening, Earthquake, and Decline

Reverend Drayton reopened the parish church eleven years after the Civil War ended, on March 26, 1876.[121][122] Worshippers arrived from Charleston by steamer to Bees Ferry and then walked to the church.[123] Funding for needed repairs likely came from income from land sales for phosphate mining along the Ashley River, which brought a short-lived economic boom to the area.[124][125] Ten years after the reopening, the church was severely damaged by the Great Charleston Earthquake of 1886.[126][127] Its epicenter was located just seven miles north of the parish church near Middleton Place.[128] As Reverend Drayton's health continued to deteriorate, his black congregation assumed new leadership.[129] Magwood's Chapel, the focus of worship and instruction, was given its own name: St. Andrew's Church, Charleston County, later known as St. Andrew's Mission Church.[129] John Grimké Drayton died on April 2, 1891, at Linwood, his daughter Julia's home in Summerville.[130]

20th Century: Dormancy and Resurgence

Vacancy and Historical Curiosity

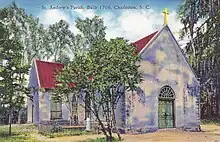

Reverend Drayton was not replaced, and the church became dormant for the next fifty-seven years.[131] The wardens and vestry tried to maintain the building and keep vandals out.[132] After three of them died in close succession, the remaining leaders relinquished control of the church in 1916 to the Diocese of South Carolina.[133] The diocese made needed repairs to the building over many years.[134] From 1923 to 1946 Rev. Wallace Martin held occasional services in the church.[135] The building became a historical curiosity; numerous postcards depicting the vacant Old St. Andrew's were produced during this time.[136] In 1937 the Hanahans of Millbrook plantation installed the cherub and decorative grapevines over the reredos at the east end as a gift commemorating a family wedding.[137] In 1940 Old St. Andrew's was documented and photographed, and elements of the church were illustrated as part of the federal government's Historic American Buildings Survey.[138]

Reopening after World War II

With Old St. Andrew's closed, Episcopalians had organized a new church, All Saints' Mission, closer to where they lived, near the Ashley River along the Savannah Highway/Folly Road area.[139] They wanted to build a new church, since reopening the dilapidated colonial church many miles away seemed overwhelming.[139] But they were unable to make a new church a reality and reluctantly reopened St. Andrew's Parish Church on Easter Day, March 28, 1948.[140] Rev. Lawton Riley was named priest in charge.[141]

Soon afterwards termites were found in the walls of the church and the building was closed for repair for almost two years.[142] Old plaster was stripped off the walls and ceiling to get to the wooden studs and trusses.[141] Damaged pews, window sills, and shutters were repaired, the reredos was cleaned, and the roof and exterior trim were painted.[141] An oil heater was installed in the north transept by the door.[141] An eighteenth-century red tile commemorating Fitch and Rose was likely removed to make room for the flue along the north transept wall.[143] Memorial tablets dedicated to John Grimké Drayton and Drayton Franklin Hastie, who had fought to keep the church under vestry control before his death in 1916, were placed opposite to each other on the south and north walls of the nave, respectively.[144] The first electric lighting was installed, along the tops of the walls.[145] Colonel William Izard Bull's plan of the new pews he installed in 1855 was discovered on the north wall of the nave, and the electricians who installed the lighting etched their names above it.[145] Instead of being preserved, the artifact was covered by the Hastie memorial.[145]

Paying for ongoing repairs became a never-ending task.[146] The glebe which dated to colonial times was sold.[147] The church held a seemingly endless number of fundraisers, the most enduring of which is Tea Room.[146] As ladies of the church would prepare the building for Sunday worship in the spring, visitors traveling up Magnolia Gardens Road to see the Ashley River plantations in bloom would see cars parked by the church. They would ask the ladies where they could get something to eat, since there were no commercial establishments anywhere nearby. These enterprising women began bringing sandwiches, coffee, and desserts and served visitors out of their cars, then on picnic tables, then in the parish house once it was built.[148] A Gift Shop offering handmade wares and foods was added.[148] Tea Room and Gift Shop has remained a fixture on the church calendar for more than seventy years.[148][149]

Growth and Uncertainty

Rev. Lynwood Magee arrived in 1952 and led the church during its most explosive period of growth, the baby boom of the fifties and sixties.[150] During his tenure the number of baptized members and communicants quadrupled.[151] The church regained full parish status in 1955, having been admitted to the diocese as an organized mission after the reopening.[152][153] A simple, concrete block parish house was built in 1953, then expanded twice (1956 and 1962) to accommodate an ever-growing number of parishioners and Sunday school students.[154]

Reverend Magee left Old St. Andrew's in 1963 for All Saints' Church in Florence, South Carolina.[151] He was followed by four rectors over the next twenty-two years, one of whom served eleven years and three with short tenures.[155] This period was marked by decreasing financial commitments due to donor fatigue, apathy, and internal difficulties.[155]

The church received a needed facelift in 1969.[156] The exterior walls were repaired and repainted.[156] The interior walls and pews were painted light blue.[156] The sandstone paver floor, which had been set in the dirt, had become unstable and needed leveling and mortaring. When the floor was taken up, the 1764 paver and tile floor was found underneath it. The old floor was more attractive and durable, so it was set in the current pattern and mortared into place.[156] The cross of St. Andrew (an X) was placed at the crossing of the aisles and the west end.[156]

The tenure of Rev. John Gilchrist (1970–81) brought renewed energy to the church.[157] The front of the parish house was expanded to include a large seating area and expanded kitchen.[158] In 1973 Old St. Andrew's was placed on the National Register of Historical Places[6] and celebrated the 25th anniversary of the 1948 reopening.[159] Parishioners marked the national bicentennial by wearing period dress.[160][161] Gilchrist guided both the church and the diocese through the Episcopal Church's difficult revision of the Book of Common Prayer.[162] When the revised book took effect in 1979 a number of dissatisfied parishioners left and founded St. Timothy's Anglican Catholic Church nearby.[163]

Confidence Regained

The tenure of rector George Tompkins (1987-2006) brought needed stability.[164] Just two years after he arrived, Hurricane Hugo struck Charleston. It spared the parish church, but caused heavy damage to the parish house, toppled more than 200 trees in the churchyard, and upended gravestones and coping.[165][166] Clearing the debris and restoring the building and grounds took more than a year.[167] The blue walls and pews of the church were repainted white.[168] The education wing of Magee House, built in 1963, received much-needed repairs.[169] Paying for these projects put a constant strain on parish finances.[170] In 1990 the main dining room of the parish house was named Gilchrist Hall after Rev. John Gilchrist.[171] Two years later the parish house was named Magee House in honor of Rev. Lynwood Magee.[168] By the end of the nineties Old St. Andrew's had 701 members, 21 percent more than at the beginning of the decade.[172]

21st Century: Continued Growth and Renewal

Great Restoration and 300th Anniversary

As the millennium approached, the vestry began planning for the church's 300th anniversary in 2006.[173] Structural engineers were hired to inspect the building. What they found was disturbing. Differential building settlement had caused the gabled walls to tilt outward.[174][175][176] The 1764 roof rafters were too small, and some of the collar ties had pulled away from them.[174][175][176] The walls were pushed outward, in some places eight inches off plumb.[174][175][176] The effects of the 1886 earthquake were also seen.[174][175][176] The report was sobering: "the under-size rafters posed an immediate life safety concern".[177][178]

The estimated cost of these and other needed repairs came to $1.2 million.[178] Parishioner and outside gifts amounted for about 40 percent of the total, with the rest financed.[179] The church was closed for about a year, beginning in April 2004.[180][181] Virtually the entire building was restored.[182][183][184] The church reopened on Easter Day 2005, fifty-seven years after the church was reopened in 1948.[185][186]

The church celebrated its tercentennial with a year-long series of activities in 2005-6.[187] Reverend Tompkins, who had been battling rheumatoid arthritis, resigned in March 2006.[188] He was succeeded by Rev. Marshall Huey, who was elected the church's 19th rector and installed on November 5, 2006.[189]

Parish Life

The parish's most immediate financial need was paying off the $729,000 restoration mortgage, which it did in just six years.[189][190] The relationship between Old St. Andrew's and St. Andrew's Mission Church, founded in 1845 as Magwood's Chapel, was strengthened through the intentional dialogue between Huey and Rev. James Yarsiah and then Rev. Jimmy Gallant of St. Andrew's Mission.[191] The first Easter Sunrise service was held at Drayton Hall in conjunction with St. Andrew's Mission Church to more closely tie the churches to the wider West Ashley community.[192] It was later moved to Magnolia Plantation and Gardens, where it continues today.[193] In 2008 a Family Service, which augments the two other Sunday worship services, was begun to appeal to families with young children.[194] Missionary efforts expanded, including work in Boca Chica, Dominican Republic, and West Ashley.[195][196][197] The Old St. Andrew's Trust, which provides the church long-term financial stability, was established through a generous bequest from Dr. Mary B. Wilson.[198] In 2020 microphones and cameras were installed unobtrusively along the walls of the church and hardware and software installed in the balcony to livestream worship services during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.[199] The following year the education wing of Magee House was significantly renovated.[200]

Denominational Affiliation

In 2012 Old St. Andrew's and other churches in the diocese found themselves entangled in legal controversy after the Diocese of South Carolina disaffiliated from the Episcopal Church.[201] After a seven-week period of discernment in early 2013, parishioners of Old St. Andrew's voted three-to-one to align with the diocese and leave the national church.[202] The parish's vote mirrored that of the majority of the diocese, eighty percent of whom eventually left the Episcopal Church.[203] In 2017 the diocese and with it Old St. Andrew's joined the Anglican Church in North America (ACNA).[204]

For a decade litigation ensued between the Episcopal Church and the disaffiliated diocese and the individual churches that left with it over the question of church property ownership.[205][206][207][208][209][210] After a number of court rulings and appeals, on May 24, 2023, the South Carolina Supreme Court denied an appeal by the Episcopal Church that challenged a prior court ruling that Old St. Andrew's, and not the Episcopal Church, owns its property.[211][212]

Rectors[213]

1 Alexander Wood 1708-10 2 Ebenezer Taylor 1712-17 3 William Guy 1718-50 4 Charles Martyn 1753-70 5 Thomas Panting 1770-71 6 Christopher Ernst Schwab 1771-73 7 Thomas Mills 1787-1816 8 Joseph M. Gilbert 1824 9 Paul Trapier 1830-35 10 Jasper Adams 1835-38 11 James Stuart Hanckel 1841-49, 1849-51 12 John Grimké Drayton 1851-91 13 Lynwood Cresse Magee 1955-63 14 John L. Kelly 1963-66 15 Howard Taylor Cutler 1967-70 16 John Ernest Gilchrist 1970-81 17 Geoffrey Robert Imperatore 1982-85 18 George Johnson Tompkins III 1987-2006 19 Stewart Marshall Huey Jr. 2006-

See also

References

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ↑ Porwoll, Paul (2014). Against All Odds: History of Saint Andrew's Parish Church Charleston, 1706-2013. Bloomington, IN: WestBow Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-4908-1818-4.

- ↑ Merrens, H. Roy, ed. (1977). The South Carolina Colonial Scene: Contemporary Views, 1697-1774. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 0-87249-261-3.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 59.

- ↑ William Guy to Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, January 22, 1728, in Merrens 1977, p. 83

- 1 2 "St. Andrew's Episcopal Church, National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form, 1973". 1973. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ↑ "Old St. Andrew's Parish Church". Anglican Diocese of South Carolina. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ↑ Cooper, Thomas, ed. (1837). The Statutes at Large of South Carolina; Edited under Authority of the Legislature. Vol. 2. Columbia: A. S. Johnston. pp. 282–294. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 10-15.

- ↑ Cooper (1837). The Statutes at Large of South Carolina. Vol. 2. pp. 328–330. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 5-9.

- ↑ Cooper (1838). The Statutes at Large of South Carolina. Vol. 3. pp. 9–11. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 42.

- ↑ Reynolds, Michael S. (2006). "St. Andrew's Parish". In Edgar, Walter (ed.). The South Carolina Encyclopedia. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. p. 823. ISBN 978-1-57003-598-2. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 18-21.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 23-25.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 25-27.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 27-29.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 30.

- ↑ Ebenezer Taylor to SPG, April 18, 1716, SPG Letters, series A, vol. 11, no. 64, pp. 233–244.

- ↑ Taylor to SPG, February 15, 1716, SPG Letters, series B, vol. 4I, pp. 168–198.

- ↑ Taylor to SPG, April 23, 1719, SPG Letters, series A, vol. 13, pp. 268-277.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 31-41.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 39.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 40-42.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 45, 72-73.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 45, 58, 69, 72.

- ↑ Guy to SPG, September 28, 1719, SPG Letters, series A, vol. 13, pp. 298-299.

- ↑ Guy to SPG, May 19, 1720, SPG Letters, series A, vol. 13, pp. 287-288.

- ↑ Guy to SPG, Jul 5, 1721, SPG Letters, series A, vol. 15, pp. 50-51.

- ↑ Guy to the Bishop of London, March 17, 1724, SPG Letters, Fulham Papers, no. 194.

- ↑ Guy to SPG, January 22, 1728, in Merrens 1977, pp. 81-86.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 47-50

- ↑ Porwoll, Paul (2018). Register of Saint Andrew's Parish Church, Charleston, SC (PDF). Vol. I: 18th Century. Charleston: Saint Andrew's Parish Church. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 50-56.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 68-69.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 69.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 65-66.

- 1 2 Porwoll 2014, p. 66

- ↑ Dalcho, Frederick (1820). An Historical Account of the Protestant Episcopal Church in South-Carolina, from the First Settlement of the Province to the War of Revolution. Charleston: E. Thayer. p. 338. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 58.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 58-64.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 58-59.

- ↑ Dorsey, Stephen P. (1952). Early English Churches in America: 1607-1807. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 94. LCCN 52-9429.

- ↑ Nelson, Louis P. (2008). The Beauty of Holiness: Anglicanism and Architecture in Colonial South Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8078-3233-2.

- ↑ Coclanis, Peter A. (2006). "Rice". In Edgar (ed.). The South Carolina Encyclopedia. p. 823. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ↑ Littlefield, Daniel C. (2006). "Slave Trade". In Edgar (ed.). The South Carolina Encyclopedia. pp. 876–877. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ↑ "Documents concerning Rev. Samuel Thomas, 1702-1707". South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine. 5 (1): 33–34. 1904. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ↑ Guy to SPG, January 22, 1728, in Merrens 1977, pp. 84-85.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 74.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 92.

- ↑ Pinckney, Elise (2006). "Pinckney, Eliza Lucas". In Edgar (ed.). The South Carolina Encyclopedia. pp. 728–729. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 77-78.

- ↑ William George Bentley, "Wealth Distribution in Colonial South Carolina" (PhD diss., Georgia State University, 1977), pp. 61-76.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 77.

- ↑ Miscellaneous Communications to the General Assembly, series S165029, vol. 1, record 299, 1777, South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 94.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 81.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 81-89.

- ↑ Cooper (1838). The Statutes at Large of South Carolina. Vol. 4. pp. 181–182. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 89-92.

- ↑ Porwoll, Paul (2019). Surprises at Every Turn: An Architectural Tour of Old St. Andrew's (PDF). Charleston: Saint Andrew's Parish Church. pp. 10–15, 17, 23. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ↑ Porwoll 2019, pp. 13-15.

- ↑ Charles Martyn to SPG, January 8, 1754, in Dalcho 1820, p. 340.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 76.

- ↑ Porwoll 2019, p.10.

- ↑ Porwoll 2019, p. 23.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 63.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 92-93.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 93-94.

- 1 2 Porwoll 2014, p. 101.

- ↑ Ewald, Captain Johann (1979). Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal. Translated by Tustin, Joseph P. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 208–214. ISBN 0-300-02153-4. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 95-97.

- ↑ Ewald 1979, pp. 214-220.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 96.

- 1 2 Petitions to the General Assembly, series S165015, vol. 60 (Report). South Carolina Department of Archives and History. 1785.

- 1 2 3 Porwoll 2014, p. 98

- 1 2 Thomas, Albert Sidney (1957). A Historical Account of the Protestant Episcopal Church in South Carolina 1820-1957 Being a Continuation of Dalcho's Account 1670-1820. Columbia: Bryan. p. 333. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ↑ Cooper (1838). The Statutes at Large of South Carolina. Vol. 4. pp. 703–704. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 107-108.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 102.

- ↑ Ruffin, Edmund (1992). Mathew, William M. (ed.). Agriculture, Geology, and Society in Antebellum South Carolina: The Private Diary of Edmund Ruffin, 1843. Athens: University of Georgia Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-8203-1324-5.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 107.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 108.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 108-109.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 109-115.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 115-118.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 113.

- ↑ Bull, Henry DeSaussure (1961). The Family of Stephen Bull of Kinghurst Hall, County Warwick, England, and Ashley Hall, South Carolina 1600-1960. Georgetown, SC: Winyah. p. 133.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 140.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 118-130.

- 1 2 3 Porwoll 2014, p. 119

- ↑ Journal of the Proceedings of the Annual Convention, Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of South Carolina [JAC, PECSC], 1841. Charleston: A. E. Miller. 1841. p. 40. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ JAC, PECSC. 1843. p. 53. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- 1 2 Porwoll 2014, p. 120

- ↑ JAC, PECSC. 1843. p. 15. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ Porwoll, Paul (2018). "In My Trials, Lord, Walk with Me": What an Antebellum Parish Register Reveals about Race and Reconciliation. Charleston: Saint Andrew's Parish Church and Saint Andrew's Episcopal Mission Church. pp. 202–243. ISBN 978-0-692-06931-8.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 122-125.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 125.

- ↑ Porwoll 2018, p. 25.

- 1 2 Porwoll 2014, p. 132

- ↑ Porwoll 2018, p. 27.

- ↑ Porwoll 2018, p. 235.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 136-141.

- 1 2 3 Porwoll 2014, p. 150

- ↑ Porwoll 2018, p. 30.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 151.

- ↑ Porwoll 2018, p. 119.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 133.

- 1 2 Porwoll 2014, pp. 164-165

- 1 2 JAC, PECSC. 1868. p. 84. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- 1 2 Porwoll 2014, p. 163

- ↑ Edgar, Walter (1998). South Carolina: A History. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. p. 382. ISBN 1-57003-255-6.

- 1 2 3 Porwoll 2014, pp. 119-120

- ↑ JAC, PECSC. 1867. p. 50. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- 1 2 3 4 Porwoll 2014, pp. 165-166

- ↑ JAC, PECSC. 1869. p. 94. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ JAC, PECSC. 1875. p. 106. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- 1 2 Porwoll 2014, p. 174

- ↑ JAC, PECSC. 1880. pp. 103, 151. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ JAC, PECSC. 1868. p. 162. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 167-169.

- ↑ St. Andrew's Church: 1706 and 1876, Vertical File 30-07-20, South Carolina Historical Society. Includes a Charleston News and Courier classified ad for steamer service to the church for its reopening.

- ↑ McKinley, Shepherd W. (2006). "Phosphate". In Edgar (ed.). The South Carolina Encyclopedia. pp. 719–720. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 171-174.

- ↑ JAC, PECSC. 1887. p. 77. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 176-178.

- ↑ Peters, Kenneth E. (2006). "Earthquakes". In Edgar (ed.). The South Carolina Encyclopedia. p. 281. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- 1 2 Porwoll 2014, pp. 180-183

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 181.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 183-210.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 188-191.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 191-193.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 193-196.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 200-207.

- ↑ Porwoll, Paul (2021). A Pictorial History of Saint Andrew's Parish Church (PDF). Vol. I: Exterior. Charleston: Saint Andrew's Parish Church. pp. 18–20. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ Porwoll, Paul (2021). A Pictorial History of Saint Andrew's Parish Church (PDF). Vol. II: Interior. Charleston: Saint Andrew's Parish Church. p. 9. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ "St. Andrew's Episcopal Church, State Route 61, Charleston, Charleston County, SC". 1940. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- 1 2 Porwoll 2014, pp. 207-209

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 209-210.

- 1 2 3 4 Porwoll 2014, p. 212

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 211-212.

- ↑ Porwoll, Paul (2015). Yesterday and Today: Four Centuries of Change at Old St. Andrew's (PDF). Charleston: Saint Andrew's Parish Church. p. 8. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 212-213.

- 1 2 3 Porwoll 2014, p. 213

- 1 2 Porwoll 2014, pp. 213-215, 228-231

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 214.

- 1 2 3 Porwoll 2014, pp. 214-215

- ↑ The Church Women of Old St. Andrew's Annual Report (CW-OSA) 2022, in St. Andrew's Parish Church: 2022 Annual Report, January 29, 2023, p. 31.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 221-222.

- 1 2 Porwoll 2014, p. 240.

- ↑ JAC, PECSC 1955, pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 235-236.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 222-225.

- 1 2 Porwoll 2014, pp. 241-275

- 1 2 3 4 5 Porwoll 2014, pp. 250-251

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 255-256, 260-263.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 259-260.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 263.

- ↑ Jacobs, Nancy (1976-10-05). "Day Captures Colonial Mood: Past Linked to Future". Post and Courier. Charleston.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 264.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 265-268.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 268.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 276-306.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 280-282.

- ↑ Porwoll 2021, Exterior, p. 42.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 281.

- 1 2 Porwoll 2014, p. 283

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 283-284.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 284-285.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 282.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 287.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 288.

- 1 2 3 4 4SE Structural Engineers (2002). "Preliminary Structural Evaluation, St. Andrews Church, Charleston, South Carolina". In Glenn Keyes Architects (ed.). Preservation Plan for Old St. Andrews Episcopal Church, 2604 Ashley River Road, Charleston, South Carolina, November 26, 2002. Charleston: Glenn Keyes Architects.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 Leake, Larry (2005). Old St. Andrews Episcopal Church: Construction Documentation. A Report Prepared for the Old St. Andrews Vestry, Charleston, SC, and Glenn Keyes, Architect AIA. Charleston: Richard Marks Restorations. pp. 2–3.

- 1 2 3 4 Porwoll 2014, p. 291

- ↑ Leake 2005, p. 3.

- 1 2 Porwoll 2014, p. 292.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 293-294.

- ↑ "Making Room for Renewal". Post and Courier. Charleston. 2004-04-26.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 294.

- ↑ Leake 2005, pp. 4-16.

- ↑ Porwoll 2021, Interior, pp. 24-32

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 294-302.

- ↑ Gartland, Michael (2005-03-27). "Historic Church Celebrates Easter Rebirth: 10-Month Project Restores Faded Luster to Old St. Andrew's". Post and Courier. Charleston.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 301.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 303-305.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 305-306.

- 1 2 Porwoll 2014, p. 308.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Rector for 2015, in St. Andrew's Parish Church: 2015 Annual Report, January 31, 2016.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 313, 316-317.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 313-314.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 319.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 313.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 310, 313, 315.

- ↑ Dominican Republic Mission Council Report 2022, in St. Andrew's Parish Church: 2022 Annual Report, January 29, 2023, pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Outreach Committee Annual Report 2022, in St. Andrew's Parish Church: 2022 Annual Report, pp. 33-35.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Rector, January, 2015, in St. Andrew's Parish Church: 2014 Annual Report, January 25, 2015.

- ↑ Porwoll 2021, Interior, p. 35.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Rector for 2021, in St. Andrew's Parish Church: 2021 Annual Report, January 30, 2022.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 319-321.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, pp. 321-324.

- ↑ Lewis, Rev. Canon Jim (2013-10-02). "The Real Story behind Our Split with the Episcopal Church". Mercury. Charleston.

- ↑ Parker, Adam (2017-03-11). "Diocese of South Carolina Joins ACNA". Post and Courier. Charleston. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ "National Episcopal Church Asks for Judge to Reconsider Ruling". Post and Courier. Charleston. 2015-02-14. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ Hawes, Jennifer Berry; Parker, Adam (2017-08-02). "State Supreme Court Rules the Episcopal Church Can Reclaim 29 Properties from Breakaway Parishes". Post and Courier. Charleston.

- ↑ Diocese of South Carolina, Federal Judge Enjoins Use of Diocese Names and Seal, September 20, 2019.

- ↑ "Judge Dickson Rules in Favor of Anglican Diocese of S.C." Mercury. Charleston. 2020-06-20. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ Dennis, Rickey Ciapha Jr. (2022-04-20). "SC Supreme Court Rules Some Breakaway Churches Must Return Properties to Episcopal Diocese". Post and Courier. Charleston. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ "SC Supreme Court Approves Petition for Rehearing Sought by Six Parishes of the Anglican Diocese of South Carolina". 2022-08-17. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ↑ Lewis, Rev. Canon Jim (Summer 2023). "South Carolina Supreme Court Final Order: Two More Anglican Parishes Have Property Rights Affirmed" (PDF). Jubilate Deo. Charleston. Retrieved 2023-06-16.

- ↑ Marshall Huey, email to Parishioners of Old St. Andrew's, May 24, 2023.

- ↑ Porwoll 2014, p. 334.