Ontario, California | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) .JPG.webp) .jpg.webp)  Clockwise: Ovitt Family Community Library; Empire Towers; Ontario Convention Center; Chaffey High School | |

Flag  Seal Coat of arms | |

| Motto: Southern California's Next Urban Center[1] | |

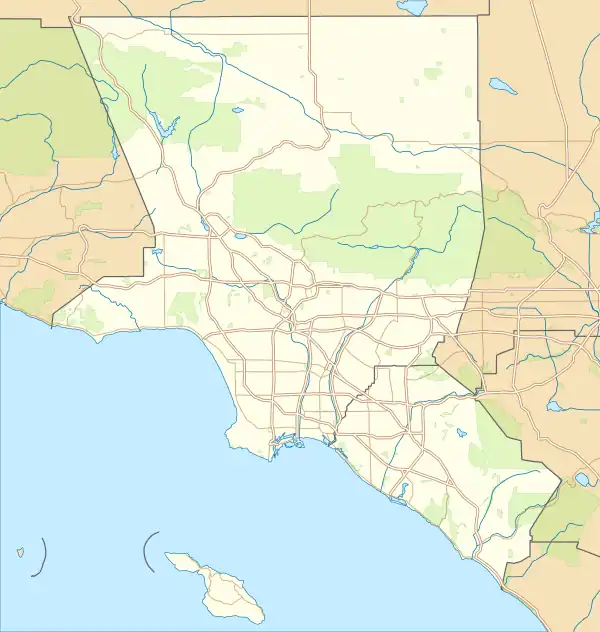

Location in San Bernardino County in California | |

Ontario, California Location in the Los Angeles metropolitan area  Ontario, California Ontario, California (California)  Ontario, California Ontario, California (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 34°03′10″N 117°37′40″W / 34.05278°N 117.62778°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | San Bernardino |

| Incorporated | December 10, 1891[2] |

| Named for | Ontario, Canada |

| Government | |

| • Type | City Council / City Manager[1] |

| • City Council[3] | Mayor Paul S. Leon Mayor Pro Tem Debra Dorst-Porada Alan D. Wapner Jim W. Bowman Ruben Valencia |

| Area | |

| • Total | 50.00 sq mi (129.50 km2) |

| • Land | 49.97 sq mi (129.43 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.08 km2) 0.13% |

| Elevation | 1,004 ft (306 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 175,265 |

| • Rank | 3rd in San Bernardino County 26th in California 149th in the United States |

| • Density | 3,507/sq mi (1,354.1/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP codes | 91758, 91761, 91762, 91764 |

| Area code | 909 |

| FIPS code | 06-53896 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1652764, 2411323 |

| Website | www |

Ontario is a city in southwestern San Bernardino County in the U.S. state of California, 35 miles (56 km) east of downtown Los Angeles and 23 miles (37 km) west of downtown San Bernardino, the county seat. Located in the western part of the Inland Empire metropolitan area, it lies just east of Los Angeles County and is part of the Greater Los Angeles Area. As of the 2020 Census, the city had a population of 175,265.[7]

The city is home to the Ontario International Airport, which is the 15th-busiest airport in the United States by cargo carried. Ontario handles the mass of freight traffic between the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and the rest of the country.[8]

It takes its name from the Ontario Model Colony development established in 1882 by the Canadian engineer George Chaffey and his brothers William Chaffey and Charles Chaffey.[9] They named the settlement after their home province of Ontario.

History

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Tovaangar (-1771)

Ontario was inhabited by the Tongva people for over 1000 years.[10] Their country is now known as Tovaangar. The Ontario area was connected to the village of Cucamonga, whose location is not now precisely known.

The Spanish Empire's New Spain Portolá expedition found and named the Santa Ana River in 1769. They also explored the Cucamonga area.[11]

Spanish Empire (1771-1822)

In 1771, Franciscans from New Spain settled in the area, and established the Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, founding what is today San Gabriel. They enslaved the Tongva people. The area was now part of the New Spain Province of Las Californias.

Juan Bautista de Anza is said to have passed through the area on his 1774 expedition. A city park and a middle school now bear his name.

In 1804, the northern part of Las Califonias became the new province of Alta California.

In 1810, the San Gabriel Franciscans took over the nearby Tongva village of Kaawchama, replacing it with the Guachama rancheria. This included a chapel devoted to San Bernadino (beginning the association of the saint with the area). The rancheria was destroyed by the Serrano in 1812.

In 1819, the San Gabriel Franciscans built the San Bernardino de Sena estancia near the earlier Guachama site.

Mexico (1822-1847)

In 1822, word of the Mexican triumph in the Mexican War of Independence reached the inland area, and the lands previously controlled by the Spanish Empire passed to the custody of the Mexican government.

In 1826, Jedediah Smith passed through what is now Upland on the first known overland journey from the east coast to the west coast of North America. He used Native American trails that he helped establish as the California Trail. (This later became the National Old Trails Road, and today's Foothill Boulevard.)[12]

Use of the San Gabriel mission's Rancho Cucamonga was in 1839 granted to Tiburcio Tapia by Mexican governor Juan Bautista Alvarado as part of the secularization of California land holdings.[13] This emancipated the Tongva enslaved there.

In 1845, the rancho was inherited by Tapia's daughter, Maria Prudhomme, and her husband Leon Prudhomme.

United States (1847-)

In January 1847, the area became controlled by the United States following the conquest of California as part of the Mexican-American War. This was formalised by the Treaty of Cahuenga that month. Under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, the United States recognised the existing land tenure, and took formal control of the land. It ruled it under a military administration until a new civilian body was established in December 1849, which became the state of California in September 1850. In February 1850, the interim California government established Los Angeles County. (The earlier Los Angeles municipal government did not cover today's Ontario.)[14]

The new Californian administration soon began a war of extermination against the Tongva, which came to be known as being part of the California genocide. 1850's Act for the Government and Protection of Indians ensured that slavery of the people it covered remained legal.[15]

San Bernadino County was founded in 1853, following the establishment of a new Mormon settlement.

Rancho Cucamonga was sold in 1858 to John Rains.

Slavery of Native Americans became illegal in California in 1865.[16]

John Rain's heirs sold Rancho Cucamonga in 1870 to an Isaias Hellman-led syndicate,[17] the "Cucamonga Company".[18] 20 years after the initial application, the California government formally converted the title of the rancho to freehold in 1872.[13][19]

In 1881, the Chaffey brothers, George and William, purchased a parcel of Hellman's Rancho Cucamonga land and the water rights to it. The land was sometimes referred to the "San Antonio lands", as they included half the water rights to Mount San Antonio[20] (colloquially known as "Mount Baldy"). They engineered a drainage system channelling water from the foothills of the mountain down to the flatter lands below that performed the dual functions of allowing farmers to water their crops and preventing the floods that periodically afflict them.

They also created the main thoroughfare of Euclid Avenue (California Highway 83), with its distinctive wide lanes and grassy median. The new "Model Colony" (called so because it offered the perfect balance between agriculture and the urban comforts of schools, churches, and commerce) was originally conceived as a dry town, early deeds containing clauses forbidding the manufacture or sale of alcoholic beverages within the town. The two named the town "Ontario" in honor of the province of Ontario in Canada, where they were from.[21]

Ontario attracted farmers (primarily growing citrus) and ailing Easterners seeking a drier climate (often to treat tuberculosis). To impress visitors and potential settlers with the "abundance" of water in Ontario, a fountain was placed at the Southern Pacific railway station. It was turned on when passenger trains were approaching and frugally turned off again after their departure. The original "Chaffey fountain", a simple spigot surrounded by a ring of white stones, was later replaced by the more ornate "Frankish Fountain", an art nouveau creation now located outside the Ontario Museum of History and Art.[22]

In 1885, the Chaffey brothers opened a campus of the University of Southern California. This included a secondary school.

Agriculture was vital to the early economy, and many street names recall this legacy. The Sunkist plant remains as a living vestige of the citrus era. The Chaffey brothers left in 1886 to found the Australian irrigation settlements of Mildura and Renmark, selling their Ontario assets to the Ontario Land & Improvement Company. Its president was Charles Frankish.[23] He founded the Ontario State Bank in 1887, the settlement's first bank.[24]

A mule-drawn tramway was used from 1887 to 1895 for public transportation on the central reservation of Euclid Avenue, operated by the Ontario and San Antonio Heights Railroad Company. Mining engineer John Tays refined its design. The two mules were loaded onto a platform at the rear of the car and allowed to ride, as gravity propelled the trolley back down the avenue to the downtown Ontario terminus. The mule car is commemorated by a replica in an enclosure south of C Street on the Euclid Avenue median.

A new wave of Mexican migrants arrived in the 1880s as railroad workers (see traquero).

Central Ontario was incorporated as a city in 1891. The municipality's territory was later greatly expanded in 1900. North Ontario broke away in 1906, calling itself Upland.[18]

The San Antonio Electric Light & Power Company was organized in 1891 to provide electricity to Ontario, Pomona and Redlands.[18] In 1895, the Ontario Electric Company was established by Charles Frankish.[24] In its first year it took over the mule-cars, and replaced them with electrical powered vehicles.[24]

Tens of thousands of European immigrants came to work in agriculture. In the early 1900s, the first Filipinos and Japanese farm laborers arrived, and later many came to own plant nurseries.[25] Another wave of Mexicans arrived after the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s. Mexican Americans at one time resided in the city's poorer central side facing State Route 60 and Chino.

In 1901, the original college closed, and a new Ontario High School replaced it. This soon became Chaffey College, and offered college courses as well as high school education.

In 1903, Ontario was proclaimed a “Model Irrigation Colony” by an act of Congress.

In 1912, the streetcar line became the Upland–Ontario Line of Pacific Electric. It was closed in 1928.

In April 1926, Euclid Ave became part of U.S. Route 66. It became the first fully paved road between the United States' east and west coasts in 1938.

In 1929, the city of Ontario established the Ontario Municipal Airport. This is now the Ontario International Airport, and is the largest employer in the city.

The city of Ontario grew quickly, increasing 10 times in the next half a century. The population of 20,000 in the 1960s grew nearly eight times more by 2007. Ontario was at one time viewed as an "Iowa under palm trees," with a solid Midwestern/Mid-American foundation, and a large German and Swiss community.

In 1960, the higher education part of Chaffey College moved to nearby Rancho Cucamonga.

From 1970 to 1980, the Ontario Motor Speedway hosted motor racing events including the California 500, and music events like California Jam.

The Cardenas supermarket chain began in Ontario in 1981.

An Ontario station of the Metrolink rail service opened in 1993.

Large shopping mall Ontario Mills opened to the public on November 14, 1996, on the old Ontario Motor Speedway parking lot.

On December 13, 1996, AMC Theatres opened AMC Ontario Mills 30 in Ontario, which it billed as the "world's largest theater".[26] Three months later, Edwards Theaters opened the Edwards Ontario Palace 22 across the street.[26] Ontario now had 52 screens on the one site, more than any other location in the United States.[26] The opening of that many screens in the Inland Empire came about as the culmination of a lifelong rivalry between AMC's Stanley Durwood and Edwards Theaters' James Edwards.[26] Edwards was infuriated when he learned Durwood had beaten him to a deal with Ontario Mills, and later told him, "I had to teach you a lesson".[26]

In 2008, the Ontario Community Events Center opened. It hosts a number of professional minor-league indoor sports teams.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 50.0 square miles (129 km2). Of that, 49.9 square miles (129 km2) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.26 km2) is water. The total area is 0.13% water.

Climate

The climate of Ontario is influenced by BSh semi-arid conditions, with hot summers and mild winters. Santa Ana Winds hit the area frequently in autumn and winter. Extremes range from 118 °F (48 °C) down to 25 °F (−4 °C). According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Ontario has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate, abbreviated "Csa" on climate maps.[27]

| Climate data for Ontario, California (Ontario International Airport) (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1998–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 90 (32) |

90 (32) |

94 (34) |

101 (38) |

103 (39) |

112 (44) |

117 (47) |

112 (44) |

118 (48) |

107 (42) |

98 (37) |

87 (31) |

118 (48) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 82.2 (27.9) |

82.9 (28.3) |

88.5 (31.4) |

94.1 (34.5) |

96.2 (35.7) |

101.4 (38.6) |

104.9 (40.5) |

106.0 (41.1) |

106.9 (41.6) |

98.9 (37.2) |

92.0 (33.3) |

80.7 (27.1) |

110.5 (43.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 67.7 (19.8) |

68.1 (20.1) |

71.7 (22.1) |

75.7 (24.3) |

79.8 (26.6) |

86.4 (30.2) |

93.8 (34.3) |

94.9 (34.9) |

91.3 (32.9) |

82.6 (28.1) |

74.7 (23.7) |

66.9 (19.4) |

79.5 (26.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 56.1 (13.4) |

57.1 (13.9) |

60.2 (15.7) |

63.4 (17.4) |

67.7 (19.8) |

73.2 (22.9) |

79.2 (26.2) |

80.1 (26.7) |

77.6 (25.3) |

69.8 (21.0) |

61.9 (16.6) |

55.2 (12.9) |

66.8 (19.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 44.6 (7.0) |

46.2 (7.9) |

48.7 (9.3) |

51.1 (10.6) |

55.6 (13.1) |

60.0 (15.6) |

64.7 (18.2) |

65.2 (18.4) |

63.8 (17.7) |

57.1 (13.9) |

49.0 (9.4) |

43.6 (6.4) |

54.1 (12.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 33.9 (1.1) |

35.0 (1.7) |

39.2 (4.0) |

44.0 (6.7) |

48.5 (9.2) |

54.9 (12.7) |

59.3 (15.2) |

59.7 (15.4) |

55.9 (13.3) |

48.4 (9.1) |

39.3 (4.1) |

33.1 (0.6) |

31.3 (−0.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 25 (−4) |

29 (−2) |

33 (1) |

33 (1) |

42 (6) |

46 (8) |

56 (13) |

56 (13) |

51 (11) |

41 (5) |

32 (0) |

28 (−2) |

25 (−4) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.57 (65) |

3.07 (78) |

1.64 (42) |

0.76 (19) |

0.30 (7.6) |

0.02 (0.51) |

0.05 (1.3) |

0.03 (0.76) |

0.10 (2.5) |

0.41 (10) |

0.80 (20) |

1.89 (48) |

11.64 (296) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 5.1 | 6.4 | 5.3 | 3.6 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 5.6 | 35.5 |

| Source: NOAA (mean maxima/minima 2006–2020)[28][29] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

The most common country of origin in Ontario is Mexico. 19.04% of Ontario's population is Mexican-born. The remaining most countries of origin in Ontario are the Philippines, El Salvador, Guatemala, Vietnam, Korea, China, Honduras, Thailand and Peru. The most common spoken languages in Ontario are Spanish, Vietnamese, Chinese, Tagalog, other Pacific Island language, Korean, Portuguese, Urdu and Arabic. Roman Catholicism is the most practiced religion.[30]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 683 | — | |

| 1900 | 722 | 5.7% | |

| 1910 | 4,274 | 492.0% | |

| 1920 | 7,280 | 70.3% | |

| 1930 | 13,583 | 86.6% | |

| 1940 | 14,197 | 4.5% | |

| 1950 | 22,872 | 61.1% | |

| 1960 | 46,617 | 103.8% | |

| 1970 | 64,118 | 37.5% | |

| 1980 | 88,820 | 38.5% | |

| 1990 | 133,179 | 49.9% | |

| 2000 | 158,007 | 18.6% | |

| 2010 | 163,924 | 3.7% | |

| 2020 | 175,265 | 6.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[31] | |||

2010

The 2010 United States Census[32] reported that Ontario had a population of 163,924. The population density was 3,278.1 inhabitants per square mile (1,265.7/km2). The racial makeup of Ontario was 83,683 (51.0%) White (18.2% Non-Hispanic White),[33] 10,561 (6.4%) African American, 1,686 (1.0%) Native American, 8,453 (5.2%) Asian, 514 (0.3%) Pacific Islander, 51,373 (31.3%) from other races, and 7,654 (4.7%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 113,085 persons (69.0%).

The Census reported that 163,166 people (99.5% of the population) lived in households, 411 (0.3%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 347 (0.2%) were institutionalized.

There were 44,931 households, out of which 23,076 (51.4%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 23,789 (52.9%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 7,916 (17.6%) had a female householder with no husband present, 3,890 (8.7%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 3,470 (7.7%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 384 (0.9%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 6,741 households (15.0%) were made up of individuals, and 2,101 (4.7%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.63. There were 35,595 families (79.2% of all households); the average family size was 3.98.

The population was spread out, with 49,443 people (30.2%) under the age of 18, 19,296 people (11.8%) aged 18 to 24, 49,428 people (30.2%) aged 25 to 44, 34,703 people (21.2%) aged 45 to 64, and 11,054 people (6.7%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29.9 years. For every 100 females, there were 99.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.8 males.

There were 47,449 housing units at an average density of 948.9 per square mile (366.4/km2), of which 24,832 (55.3%) were owner-occupied, and 20,099 (44.7%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.0%; the rental vacancy rate was 5.8%. 90,864 people (55.4% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 72,302 people (44.1%) lived in rental housing units.

During 2009–2013, Ontario had a median household income of $54,249, with 18.1% of the population living below the federal poverty line.[33]

2000

As of the census[34] of 2000, there were 158,007 people, 43,525 households, and 34,689 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,173.9 inhabitants per square mile (1,225.4/km2). There were 45,182 housing units at an average density of 907.6 per square mile (350.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 47.8% White, 7.5% African American, 1.1% Native American, 3.9% Asian, 0.4% Pacific Islander, 34.1% from other races and 5.3% were from two or more races. 59.9% were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 43,525 households, out of which 49.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56.9% were married couples living together, 15.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 20.3% were non-families. 15.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 4.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.6 and the average family size was 4.0.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 34.4% under the age of 18, 11.2% from 18 to 24, 32.4% from 25 to 44, 16.1% from 45 to 64, and 5.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 28 years. For every 100 females, there were 100.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 98.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $42,452, and the median income for a family was $44,031. Males had a median income of $31,664 versus $26,069 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,244. 15.5% of the population and 12.2% of families were below the poverty line. 19.1% of those under the age of 18 and 7.6% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.

Economy

In the years following Ontario's founding, the economy was driven by its reputation as a health resort. Shortly thereafter, citrus farmers began taking advantage of Ontario's rocky soil to plant lemon and orange groves. Agricultural opportunities also attracted vintners and olive growers. The Graber Olive House, which continues to produce olives, is a city historical landmark and one of the oldest institutions in Ontario. Dairy farming is also prevalent, as it continues to be in neighboring Chino. Much of southern Ontario still contains dairy farms and other agricultural farms.[35] However, the area is currently under planning to be developed into a mixed-use area of residential homes, industrial and business parks, and town centers, collectively known as the New Model Colony.[36]

A major pre-war industry was the city's General Electric plant that produced clothing irons. During and after World War II, Ontario experienced a housing boom common to many suburbs. The expansion of the Southern California defense industry attracted many settlers to the city.[37] With California's aerospace industry concentrated in Los Angeles and the Bay Area, the Ontario International Airport was used as a pilot training center.[38] Today, Ontario still has a manufacturing industry, the most notable of which are Maglite, which produces flashlights. Manufacturing has waned, and Ontario's economy is dominated by service industries and warehousing. Major distribution centers are operated by companies such as AutoZone, Cardinal Health, MBM, Genuine Parts/NAPA, and Nordstrom.[39]

Ontario is also home to Niagara Bottling, The Icee Company, clothing companies Famous Stars and Straps and Shiekh Shoes, Scripto U.S.A., and to Phoenix Motorcars, who employs over 150 employees in Ontario.[40]

Top employers

According to the city's 2014 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[39] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ontario International Airport | 5,000–9,999 |

| 2 | Safariland | 500–999 |

| 3 | Sam's Club Distribution | 500–999 |

| 4 | Securitas | 500–999 |

| 5 | Target Distribution | 500–999 |

| 6 | United Parcel Service (UPS) | 500–999 |

Tourism

The Greater Ontario Convention and Visitors Bureau implemented a tourism marketing district and adopted an aggressive five-year strategic plan focusing on marketing initiatives to bring visitors to the region, build brand and destination awareness while enhancing the local economy.[41]

Arts and culture

Ontario is home to three museums, the Ontario Museum of History and Art, the Chaffey Community Museum of Art, and the Ontario Police Museum.

Built in 1925, The Granada Theatre was leased to West Coast Junior Theater. By the 1940s, the theater had become part of the Fox West Coast Theater chain. The Granada Theatre was designed by architect L.A. Smith.[42]

Ontario is also the home to the second largest consumer Quilt Show in the United States, Road to California. The quilt show books over 2,400 room nights and has a recorded attendance of over 40,000 attendees.[43]

The Ontario post office contains two oil on canvas murals, The Dream depicting founder Chaffey with surveyors and The Reality which shows a view of the completed Euclid Avenue, painted by WPA muralist Nellie Geraldine Best in 1942.[44]

Since 1959, Ontario has placed three-dimensional nativity scenes on the median of Euclid Avenue during the Christmas season. The scenes, featuring statues by the sculptor Rudolph Vargas, were challenged in 1998 as a violation of church-state separation under the California Constitution by an atheist resident, but the dispute was resolved when private organizations began funding the storage and labor involved in the set-up and maintenance of the scenery in its entirety.[45] To support the nativity scenes the Ontario Chamber of Commerce started a craft fair called "Christmas on Euclid".

The All-States Picnic, an Independence Day celebration, began in 1939 to recognize the varied origins of the city's residents. Picnic tables lined the median of Euclid Avenue from Hawthorne to E Street, with signs for each of the country's 48 states. The picnic was suspended during World War II, but when it resumed in 1948, it attracted 120,000 people. A 1941 Ripley's Believe It or Not! cartoon listed Ontario's picnic table as the "world's longest". As native Californians came to outnumber the out-of-state-born, the celebration waned in popularity until it was discontinued in 1981. It was revived in 1991 as a celebration of civic pride.[46]

Sports

The Toyota Arena is a multipurpose arena which opened in late 2008. It is owned by Ontario, but is operated by SMG Worldwide. It is an 11,000-seat multi-purpose arena, the largest enclosed arena in the Inland Empire. Over 125 events are held annually featuring sporting competitions, concerts, and family shows.

The arena had been the home of the Ontario Reign, a former team in the ECHL, that called the arena home from 2008 to 2015. The Los Angeles Kings' affiliate played at the 9,736-seat Toyota Arena. In their debut season of 2008–09, they were second in the league in attendance, averaging 5856 fans per game.[47] The Reign led the ECHL in average attendance in every subsequent year.

In January 2015, the American Hockey League, a minor league above the ECHL, announced that it was forming a new Pacific Division and would be replacing the ECHL Ontario Reign with a relocated team. The Kings relocated the Manchester Monarchs, a franchise they had owned and operated since 2012, and became the Ontario Reign beginning with the 2015–16 AHL season.

The Ontario Motor Speedway was located in Ontario, and held races for USAC, Formula One, NHRA, and NASCAR. It was demolished in 1980 after the Chevron Land Company bought the property.[48]

| Club | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empire Strykers | MASL, Indoor soccer | Toyota Arena | 2013 | 0 |

| Ontario Reign | American Hockey League, Ice hockey | Toyota Arena | 2015 | 1 |

| Ontario Clippers | NBA G League, Basketball | Toyota Arena | 2017 | 0 |

Government

Local government

The city is governed by a five-member council.

According to the 2009 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, the city's various funds had $399.4 million in revenues, $305.3 million in expenditures, $1,606.0 million in total assets, $317.6 million in total liabilities, and $412.4 million in cash and investments.[49]

State and federal representation

In the California State Legislature, Ontario is in the 20th Senate District, represented by Democrat Caroline Menjivar, and in the 52nd Assembly District, represented by Democrat Wendy Carrillo.[50]

In the United States House of Representatives, Ontario is in California's 35th congressional district, represented by Democrat Norma Torres.[51]

Education

Ontario has five school districts: Ontario/Montclair Elementary, Mt View Elementary, Cucamonga Elementary, Chino Unified and Chaffey Joint Union in the City borders. There are also several private schools throughout the city as well as two private military schools. Ontario also has nine trade schools. The University of La Verne College of Law is located in downtown Ontario. National University, Argosy University, San Joaquin Valley College and Chapman University have a satellite campus near the Ontario Mills mall. Ontario Christian is located there. Gateway Seminary has a campus in Ontario.[52]

Infrastructure

Transportation

The Ontario International Airport provides domestic and international air travel. Because of the many manufacturing companies and warehouses in the city, the airport also serves as a major hub for freight, especially for FedEx and UPS.

Because Ontario is a major hub for passengers and freight, the city is also served by several major freeways. Interstate 10 and the Pomona Freeway (State Route 60) run east–west through the city. Interstate 10 is north of the Ontario airport while the Pomona freeway is south of the airport. Interstate 15 runs in the north–south directions at the eastern side of the city. State Route 83, also known as Euclid Avenue, also runs in the north–south direction at the western side of the city.

The city maintains an Amtrak station which is served by the Sunset Limited and Texas Eagle lines. Ontario also has a Metrolink station off of Haven Avenue. It connects Ontario with much of the Greater Los Angeles area, Orange County and the San Fernando Valley. Public bus transportation is provided by Omnitrans. Additional bus and rail connections to Los Angeles and elsewhere are available at the nearby Montclair station. A bus rapid transit line known as the sbX Purple Line is currently being constructed, which will run through the city.

Cemeteries

The Bellevue Memorial Park is located on West G Street.[53][54] Spanish–American War Congressional Medal of Honor recipient Frank Fulton Ross is buried there, as is George Chaffey, one of the two founders of the city.[55]

Shopping

Ontario Mills is a major shopping mall in Ontario, while Cardenas, a supermarket chain specializing in Latin American cuisine, was founded in and is based in Ontario.

Notable people

- Hobie Alter, pioneer surfboard maker and catamaran builder

- Jeff Ayres, basketball player, NBA champion with the San Antonio Spurs

- Rod Barajas, MLB player for the Los Angeles Dodgers and six other MLB teams

- Madge Bellamy, actress[56]

- Jim Brulte, politician[57]

- Jason Bowles, stock car racing driver

- Eudora Stone Bumstead (1860–1892), poet, hymnwriter

- Henry Bumstead, Academy Award-winning cinematic art director and designer

- Beverly Cleary, author and Newbery Medal-winning novelist (1984), The Luckiest Girl and memoir My Own Two Feet

- Andy Clyde, actor, married in Ontario in 1932

- Del Crandall, MLB player and manager, 11-time All-Star, member of 1957 World Series champion Braves

- William De Los Santos, poet, screenwriter and film director

- Joseph Dippolito, former underboss of the Dragna crime family

- Landon Donovan, former Los Angeles Galaxy and USMNT player; born in Ontario, raised in Redlands

- Prince Fielder, baseball player for the Texas Rangers

- José Carrera García, professional footballer

- Ana Patricia González, winner of Nuestra Belleza Latina 2010 (Our Latin Beauty 2010) and currently appearing on ¡Despierta América![58]

- Bill Graber, pole vaulter

- Robert Graettinger, composer

- Cle Kooiman, soccer player

- Ryan Lane, actor

- Nick Leyva, manager of the Philadelphia Phillies (1989–1991)[59]

- Christina "T" Lopez, singer, actress; former member of Latin girl dance-pop band Soluna[60]

- Sam Maloof, furniture designer and woodworker

- Shelly Martinez, professional wrestler

- Anthony Muñoz, 1998 Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee

- Al Newman, former MLB player [61]

- Douglas Northway, Olympic bronze medalist, swimming[62]

- Joan O'Brien, actress, graduate of Chaffey Union High School District

- Charles Phoenix, pop culture humorist, historian, author and chef

- Antonio Pierce, football player

- Joey Scarbury, singer[63]

- Robert Shaw, conductor[64]

- Mike Sweeney, MLB player for Philadelphia Phillies, attended Ontario High School and led 1991 baseball team to undefeated record and state title[65]

- Bobby Wagner, football player, attended Colony High School; middle Linebacker for the Super Bowl champions Seattle Seahawks

- Joseph Wambaugh, author[57]

- Frank Zappa, musician, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award[66]

Sister cities

Ontario has five sister cities around the world.[67] They are:

.svg.png.webp) Brockville, Ontario, Canada (since 1977)

Brockville, Ontario, Canada (since 1977) Guamúchil, Sinaloa, Mexico (since 1982)

Guamúchil, Sinaloa, Mexico (since 1982) Mocorito, Sinaloa, Mexico (since 1982)

Mocorito, Sinaloa, Mexico (since 1982) Los Mochis, Sinaloa, Mexico (since 1988)

Los Mochis, Sinaloa, Mexico (since 1988).svg.png.webp) Winterthur, Canton of Zürich, Switzerland[note 1][68]

Winterthur, Canton of Zürich, Switzerland[note 1][68] Jieyang, China[69]

Jieyang, China[69]

See also

Notes

- ↑ However, according to the official website by the city of Winterthur, Ontario is not one of its partner cities.

References

- 1 2 "City Facts". City of Ontario. Archived from the original on December 19, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ↑ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on February 21, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ "Public Officials". City of Ontario, California. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ↑ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ↑ "Ontario". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- ↑ "QuickFacts: Ontario city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Census - Geography Profile: Ontario city, California". Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ↑ "Ontario: Inland Empire Urban Center". Inlandempireoutlook.org. November 26, 2009. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ↑ History of Ontario Archived April 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ↑ Early Ontario. Arcadia. 2014. ISBN 9781467132404.

- ↑ "Rancho Cucamonga". Bureau of Land Management. September 17, 2020.

- ↑ Delja, Beatrice. "CHL # 781 National Old Trails Monument San Bernadino [sic]". www.californiahistoricallandmarks.com. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- 1 2 Prudhomme, Leon Victor; Tapia, Tiburcio; Prudhomme, Leon Victor; United States District Court (California: Southern District) (eds.). Cucamonga [San Bernardino County] Leon V. Prudhomme, Claimant. Case no. 214, Southern District of California. 1852-1864.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ Guinn, J. M.; Stearns, Abel; Valdez, Bacillo; Herrera, Jose M. (1907). "FROM PUEBLO TO CIUDAD. The Municipal and Territorial Expansion of Los Angeles". Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California. 7 (2/3): 216–221. doi:10.2307/41168646. ISSN 2162-9145.

- ↑ Compiled laws of the State of California: containing all the acts of the Legislature of a public and general nature, now in force, passed at the sessions of 1850-51-52-53, Benicia, S. Garfeilde, 1853. pp. 822-825 An Act for the Government and Protection of Indians

- ↑ Dutschke, Dwight (2014). "A History of American Indians in California" (PDF). California Office of Historic Preservation, Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey for California. Retrieved October 10, 2016.

- ↑ Richardson, Katie. "Guides: Pomona Valley Historical Collection: Ranchos". libguides.library.cpp.edu. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- 1 2 3 Brown, John; Boyd, James (1922). History of San Bernardino and Riverside counties / with selected biography of actors and witnesses of the period of growth and achievement. Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center. [Madison, Wis.] : The Western Historical Association.

- ↑ "Report of the Surveyor General 1844–1886" (PDF). State of California. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 20, 2013 – via slc.ca.gov.

- ↑ Hackenberger, Benjamin C. "The San Antonio Wash: Addressing the Gap Between Claremont and Upland".

- ↑ Historic Preservation | City of Ontario, California

- ↑ "The City of Ontario's Citrus Industry" (PDF).

- ↑ https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/5038fc9f-c181-414a-8b78-cffcf286ff6b

- 1 2 3 "California Genealogy Trails - Californian American Bios page 8". genealogytrails.com. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ↑ "City History - DOIA".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hayes, Dade; Bing, Jonathan (2004). Open Wide: How Hollywood Box Office Became a National Obsession. New York: Miramax Books. pp. 311-317. ISBN 1401352006.

- ↑ "Ontario, California Travel Weather Averages (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ↑ "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Ontario INTL AP, CA". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ↑ "_Ontario AFH Final Draft" (PDF).

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA – Ontario city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- 1 2 "Ontario (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 18, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ Singh, Maanvi (September 13, 2022). "'Monstrosities in the farmland': how giant warehouses transformed a California town". The Guardian. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ↑ Khouri, Andrew (November 6, 2014) "Ontario housing development restarts after stalling during recession" Los Angeles Times

- ↑ Bakken, Gordon Morris; Alexandra Kindell (2006). Encyclopedia of immigration and migration in the American West. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications.

- ↑ City History Retrieved 2017-10-21

- 1 2 "City of Ontario CAFR". Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ↑ Ken Bensinger (April 5, 2008). "Road for electric car makers full of potholes". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 3, 2011.

- ↑ "Greater Ontario Visitors and Convention Bureau". www.discoverontariocalifornia.org. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ↑ "City of Ontario Designated Landmarks" (PDF).

- ↑ "Ontario Convention Center attracting more and more conventions". dailybulletin.com. February 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Murals will adorn walls of post office". The San Bernardino County Sun. San Bernardino Country Sun. October 29, 1942. p. 15. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ↑ "chaffey.org". chaffey.org. December 22, 1999. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ↑ "dailybulletin.com". dailybulletin.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ↑ "ECHL 2008-09 team attendance at hockeydb.com". hockeydb.com. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ↑ "California 500 Dreaming : It Was Fun While It Lasted at Ontario Motor Speedway (1970-1980)". Los Angeles Times. November 27, 1995.

- ↑ City Ontario CAFR Archived January 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2009-08-14

- ↑ "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ↑ "California's 35th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ↑ Education | City of Ontario, California

- ↑ "Bellevue Memorial Park". Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- ↑ "Bellview Cemetery". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ vconline.org.uk

- ↑ "Silent-movie star lived here, far from the limelight". www.dailybulletin.com. May 7, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- 1 2 "chaffey.org". chaffey.org. March 22, 2005. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Ana Patricia: "No quisiera vivir nunca en la Mansión de la belleza"". PeopleenEspanol.com. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Nick Leyva". Retrosheet.org. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Soluna On Fire". QV Magazine. Archived from the original on January 15, 2007.

- ↑ "Al Newman Statistics". The Baseball Cube. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Doug Northway Biography and Statistics". Sports-reference.com. April 28, 1955. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Joey Scarbury, born in Ontario, California, singer, Greatest American Hero June 7 in History". Brainyhistory.com. June 7, 1955. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Alumni Hall of Fame". Chaffey.org. March 22, 2005. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ↑ "mikesweeney.org". mikesweeney.org. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ↑ Miles, Barry (2004). Frank Zappa. London: Atlantic Books. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-84354-092-2.

- ↑ "Sister Cities". City of Ontario, California. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Partnerstädte" (official site) (in German). Winterthur, Switzerland: Stadt Winterthur. 2016. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Facts & History | City of Ontario, California".