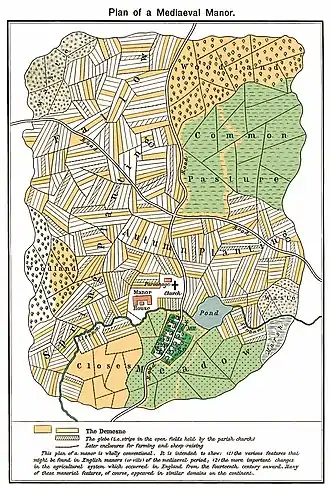

The open-field system was the prevalent agricultural system in much of Europe during the Middle Ages and lasted into the 20th century in Russia, Iran, and Turkey.[1] Each manor or village had two or three large fields, usually several hundred acres each, which were divided into many narrow strips of land. The strips or selions were cultivated by peasants, often called tenants or serfs. The holdings of a manor also included woodland and pasture areas for common usage and fields belonging to the lord of the manor and the religious authorities, usually Roman Catholics in medieval Western Europe. The farmers customarily lived in separate houses in a nucleated village with a much larger manor house and church nearby. The open-field system necessitated co-operation among the residents of the manor.

The Lord of the Manor, his officials, and a manorial court administered the manor and exercised jurisdiction over the peasantry. The Lord levied rents and required the peasantry to work on his personal lands, called a demesne.[2]

In medieval times, little land was owned outright. Instead, generally the lord had rights given to him by the king, and the tenant rented land from the lord. Lords demanded rents and labour from the tenants, but the tenants had firm user rights to cropland and common land and those rights were passed down from generation to generation. A medieval lord could not evict a tenant nor hire labour to replace him without legal cause. Most tenants likewise were not free without penalty to depart the manor for other locations or occupations. The rise of capitalism and the concept of land as a commodity to be bought and sold led to the gradual demise of the open-field system.[3] The open-field system was gradually replaced over several centuries by private ownership of land, especially after the 15th century in the process known as enclosure in England. France, Germany, and other northern European countries had systems similar to England, although open fields generally endured longer on the continent. Some elements of the open-field system were practised by early settlers in the New England region of the United States.[4][5]

Description

The most visible characteristic of the open-field system was that the arable land belonging to a manor was divided into many long narrow furlongs for cultivation. The fields of cultivated land were unfenced, hence the name open-field system. Each tenant of the manor cultivated several strips of land scattered around the manor.

The village of Elton, Cambridgeshire, is representative of a medieval open-field manor in England. The manor, whose Lord was an abbot from a nearby monastery, had 13 "hides" of arable land of six virgates each. The acreage of a hide and virgate varied; but at Elton, a hide was 144 acres (58 ha) and a virgate was 24 acres (10 ha). Thus, the total of arable land amounted to 1,872 acres (758 ha). The abbot's demesne land consisted of three hides plus 16 acres (6.5 ha) of meadow and 3 acres (1 ha) of pasture. The remainder of the land was cultivated by 113 tenants who lived in a village on the manor. Counting spouses, children, and other dependents, plus landless people, the total population resident in the manor village was probably 500 to 600.[6]

The abbot also owned two water mills for grinding grain, a fulling mill for finishing cloth, and a millpond on the manor. The village contained a church, a manor house, a village green, and the sub-manor of John of Elton, a rich farmer who cultivated one hide of land and had tenants of his own. The tenants' houses lined a road rather than being grouped in a cluster. Some of the village houses were fairly large, 50 feet (15 m) long by 14 feet (4.3 m) wide. Others were only 20 feet (6 m) long and 10 feet (3 m) wide. All were insubstantial and required frequent reconstruction. Most of the tenants' houses had outbuildings and an animal pen with a larger area, called a croft, of about one-half acre (0.2 ha), enclosed for a garden and grazing for animals.[7]

The tenants on the manor did not have equal holdings of land. About one-half of adults living on a manor had no land at all and had to work for larger landholders for their livelihood. A survey of 104 13th-century manors in England found that, among the landholding tenants, 45 percent had less than 3 acres (1 ha). To survive, they also had to work for larger landowners. 22 percent of tenants had a virgate of land (which varied in size between 24 acres (10 ha) and 32 acres (13 ha) and 31 percent had one-half virgate.[8] To rely on the land for a livelihood a tenant family needed at least 10 acres (4 ha).

The land of a typical manor in England and other countries was subdivided into two or three large fields. Non-arable land was allocated to common pasture land or waste, where the villagers would graze their livestock throughout the year, woodland for pigs and timber, and also some private fenced land (paddocks, orchards and gardens), called closes. The ploughed fields and the meadows were used for livestock grazing when fallowed or after the grain was harvested.

One of the two or three fields was fallowed each year to recover soil fertility. The fields were divided into parcels called furlongs. The furlong was further subdivided into long, thin strips of land called selions or ridges. Selions were distributed among the farmers of the village, the manor, and the church. A family might possess about 70 selions totalling about 20 acres (8 ha) scattered around the fields. The scattered nature of family holdings ensured that families each received a ration of both good and poor land and minimised risk. If some selions were unproductive, others might be productive. Ploughing techniques created a landscape of ridge and furrow, with furrows between ridges dividing holdings and aiding drainage.

The right of pasture on fallowed fields, land unsuitable for cultivation, and harvested fields was held in common with rules to prevent overgrazing enforced by the community.[9]

Crops and production

The typical planting scheme in a three-field system was that barley, oats, or legumes would be planted in one field in spring, wheat or rye in the second field in the fall and the third field would be left fallow. The following year, the planting in the fields would be rotated. Pasturage was held in common. The tenants pastured their livestock on the fallow field and on the planted fields after harvest. An elaborate set of laws and controls, partly set by the Lord of the Manor and partly by the tenants themselves regulated planting, harvest, and pasturing.[10]

Wheat and barley were the most important crops with roughly equal amounts planted on the average in England. Annual wheat production at Battle Abbey in Sussex in the late 14th century ranged from 2.26 to 5.22 seeds harvested for every seed planted, averaging 4.34 seeds harvested for every seed planted. Barley production averaged 4.01 and oats 2.87 seeds harvested for seeds planted. This translates into yields of 7 to 17 bushels per acre harvested. Battle Abbey may have been atypical, with better management and soils than typical of demesnes in open-field areas.[11] Barley was used in making beer – consumed in large quantities – and mixed with other grains to produce bread that was a dietary staple for the poorer farmers. Wheat was often sold as a cash crop. Richer people ate bread made of wheat. At Elton in Cambridgeshire in 1286, perhaps typical of that time in England, the tenants harvested about twice as much barley as wheat with lesser amounts of oats, peas, beans, rye, flax, apples, and vegetables.[12]

The land-holding tenants also had livestock, including sheep, pigs, cattle, horses, oxen, and poultry. Pork was the principal meat eaten; sheep were primarily raised for their wool, a cash crop. Only a few rich landholders had enough horses and oxen to make up a ploughing-team of six to eight oxen or horses, so sharing among neighbours was essential.[13]

History

Much of the land in the open-field system during medieval times had been cultivated for hundreds of years earlier on Roman estates or by farmers belonging to one of the ethnic groups of Europe. There are hints of a proto-open-field system going back to AD 98 among the Germanic tribes. Germanic and Anglo-Saxon invaders and settlers possibly brought the open-field system to France and England after the 5th century AD.[14] The open-field system appears to have developed to maturity between AD 850 and 1150 in England, although documentation is scarce prior to the Domesday Book of 1086.

The open-field system was never practiced in all regions and countries in Europe. It was most common in heavily populated and productive agricultural regions. In England, the south-east, notably parts of Essex and Kent, retained a pre-Roman system of farming in small, square, enclosed fields. In much of eastern and western England, fields were similarly either never open or were enclosed earlier. The primary area of open fields was in the lowland areas of England in a broad swathe from Yorkshire and Lincolnshire diagonally across England to the south, taking in parts of Norfolk and Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, large areas of the Midlands, and most of south central England. This area was the main grain-growing region (as opposed to pastoral farming) in medieval times.

The population in Europe grew in the early centuries of the open-field system, doubling in Britain between 1086 and 1300, which required increased agricultural production and more intensive cultivation of farmland.[15] The open-field system was generally not practised in marginal agricultural areas or in hilly and mountainous regions. Open fields were well suited to the dense clay soils common in northwestern Europe. Heavy ploughs were needed to cut through the soil and the ox or horse teams which pulled the ploughs were expensive, and thus both animals and ploughs were often shared by necessity among farm families.[16]

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1290574.jpg.webp)

The Black Death of 1348–1350 killed 30–60% of Europe's population.[18] As a consequence the surviving population had access to larger tracts of empty farmland and wages increased due to a shortage of labour. Richer farmers began to acquire land and remove it from communal usage. An economic recession and low grain prices in fifteenth century England gave a competitive advantage to the production of wool, meat, and milk. The shift away from grain to livestock accelerated enclosure of fields. The steadily increasing number of formerly open fields converted to enclosed (fenced) fields caused social and economic stress among small farmers who lost their access to communal grazing lands. Many tenants were forced off the lands their families may have cultivated for centuries to work for wages in towns and cities. The number of large and middle-sized estates grew in number while small land-holders decreased in number.[19] In the 16th and early 17th centuries, the practice of enclosure (particularly depopulating enclosure) was denounced by the Church and the government, and legislation was drawn up against it. The dispossession of tenants from their land created an "epidemic of vagrancy" in England in the late 16th and early 17th century.[20] The tide of elite opinion began to turn towards support for enclosure, and the rate of enclosure increased in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[21]

Controversies and inefficiencies

The open-field system is considered by many economists to have been inefficient for agricultural production and resistant to technological innovation. "Everyone was forced to conform to village norms of cropping, harvesting, and building."[22] The communal institutions, the manorial court, and the tenants regulated agricultural practices and economic behaviour. The manorial lord exercised control over the tenants by extracting rent for land or labour to cultivate his demesne lands. The scattered holdings of each farmer increased the time needed to travel to and from fields.

The open-field system, especially its characteristic of common grazing lands, has often been used as an example by economists to illustrate "the tragedy of the commons" and assert that private ownership is a better steward of resources than common or public ownership. "Tragedy of the commons" refers to the alleged destruction of common pastures in England as a result of overgrazing, each tenant maximizing his gain by grazing as many animals as possible and ignoring the long-term impact of overgrazing. The author of the term "tragedy of the commons", Garrett Hardin, pointed out that the pastures of England were "protected from ruin by limiting each tenant to a fixed number of animals". Thus, Hardin says the commons were "managed...which may be good or bad depending on the quality of the management".[23][24]

The fact that the open-field system endured for roughly a thousand years over a large part of Europe and provided a livelihood to a growing population indicates that there might not have been a better way of organizing agriculture during that time period.[25][26] However, some argue that the pastures of England were actually highly managed; they were considered to be privately owned by the village as a whole, which led to a communal sense of responsibility to maintaining the land. Managerial practices such as stinting, or limiting the amount of cattle permitted, required weed removal, removal of straw, cutting thistles, ringing swine, and knobbing cow's horns to prevent grubbing were common. The commons were regularly inspected by the villagers and sometimes by a delegation from the manorial court. It is even argued that the commons that Hardin was referring to in "The Tragedy of the Commons" were actually pre-enclosure commons, which were not true commons, but rather left over lands that were misused by the poor, displaced, and criminals.[27]

The replacement of the open-field system by privately owned property was fiercely resisted by many elements of society. Karl Marx was extremely opposed to the enclosure of the open field system, calling it a "robbery of the common lands"[28] The "brave new world" of a harsher, more competitive and capitalistic society from the 16th century onward destroyed the securities and certainties of land tenure in the open-field system.[29] The open field system died only slowly. More than half the agricultural land of England was still not enclosed in 1700, after which the government discouraged the continuation of the open-field system. It was finally laid to rest in England about 1850 after more than 5,000 Acts of Parliament and just as many voluntary agreements[30] over several centuries had transformed the "scattered plots in the open fields" into unambiguous private and enclosed properties free of village and communal control and use.[31] Over half of all agricultural land in England was enclosed during the 18th and 19th centuries.[32] Other European countries also began to pass legislation to eliminate the scattering of farm land, the Netherlands and France passing laws making land consolidation compulsory in the 1930s and 1950s respectively.[33] In Russia, the open-field system, called "cherespolositsa" ("alternating ribbons (of land)") and administered by the obschina / mir (the general village community), remained as the main system of peasant land ownership in Russia until the Stolypin reform process that started in 1905, but generally continued for many years, finally ending only with the Soviet policy of collectivisation in the 1930s.

Modern usage

One place in England where the open-field system continues to be used is the village of Laxton, Nottinghamshire. It is thought that its anomalous survival is due to the inability of two early 19th-century landowners to agree on how the land was to be enclosed, thus resulting in the perpetuation of the existing system.

The only other surviving medieval open strip field system in England is in Braunton, North Devon. It is still farmed with due regard to its ancient origins and is conserved by those who recognise its importance although the number of owners has fallen dramatically throughout the years and this has resulted in the amalgamation of some of the strips.

There is also a surviving medieval open strip field system in Wales in the township of Laugharne, which is also the last town in the UK with an intact medieval charter.

Vestiges of an open-field system also persist in the Isle of Axholme, North Lincolnshire, around the villages of Haxey, Epworth and Belton, where long strips, of an average size of half an acre, curve to follow the gently sloping ground and are used for growing vegetables or cereal crops. The boundaries are mostly unmarked, although where several strips have been amalgamated a deep furrow is sometimes used to divide them. The ancient village game of Haxey Hood is played in this open landscape.

Allotment gardens

A similar system to open fields survives in the United Kingdom as allotment gardens. In many towns and cities there are areas of land of one or two acres (up to about one hectare) interspersed between the buildings. These areas are usually owned by local authorities, or by allotment associations. Small patches of the land are allocated at a low rent to people for growing food.

References

- ↑ Keddie, Nicki R. Iran. Religion, Politics and Society: Collected Essays London: Routledge, 1980, pp. 186–187

- ↑ Astill, Grenville and Grant, Annie, eds. The Countryside of Medieval England Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1988, pp.23, 64

- ↑ Kulikoff, Allan From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000, p. 11

- ↑ Ault, W. O. Open-Field Farming in Medieval England London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1972, pp. 77–78

- ↑ Powell, Sumner Chilton. (1963). Puritan Village: The Formation of a New England Town. Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT 215pp. ISBN 0-8195-6014-6

- ↑ Gies, Frances and Joseph Life in a Medieval Village New York: Harper and Row, 1990, pp 31, 42

- ↑ Gies, pp. 34–36

- ↑ McCloskey, Donald N. "The open fields of England: rent, risk, and the rate of interest, 1300–1815" in Markets in History: Economic Studies of the Past, ed. David W. Galenson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989, pp 6–7

- ↑ "Medieval fields in their many forms" British Archaeology Issue no. 33, April 1998; Ault, W. O. "Open-Field Farming in Medieval England" London: George Allen and Unwin, Ltd., 1972, pp. 15–16

- ↑ Hopcroft, Rosemary L. Regions, Institutions, and Agrarian Change in European History Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 17–20; Astill and Grant, p. 27

- ↑ Brandon, P. F. "Cereal Yields on the Sussex Estates of Battle Abby during the Later Middle Ages," The Economic History Review, New Series, Vol. 25, No. 8 (Aug 1972), pp. 405, 412, 417, 419–420

- ↑ Gies, pp. 60–62

- ↑ Gies, pp. 82, 145–149

- ↑ Hopcroft, p. 40

- ↑ Ault, pp. 15–16, Oosthuizen, p. 165-166

- ↑ Ault, 20–21

- ↑ Whilst the stitches (strips) to the west of track across the open field were arable at the time of this visit (early May 2009), on the east side they are covered in grass. This illustrates the system whereby the stitches were cultivated by their owners during the Summer, but grazed in common during the winter. This grazing adds manure to the soil to keep it fertile.

- ↑ Austin Alchon, Suzanne (2003). A pest in the land: new world epidemics in a global perspective. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8263-2871-7.

- ↑ Hopcroft, pp 70–81

- ↑ Gies, p. 196; Kulikoff, pp. 19, 50

- ↑ Beresford, Maurice. The Lost Villages of England (Revised ed.) London: Sutton, 1998, p. 102 ff

- ↑ Hopcroft, p. 48

- ↑ Hardin, Garrett (13 December 1968). "The Tragedy of the Commons". Science. 162 (3859): 1243–8. Bibcode:1968Sci...162.1243H. doi:10.1126/science.162.3859.1243. PMID 5699198.

- ↑ Hardin, Garret, "The Tragedy of the Commons", accessed 22 August 2019

- ↑ Dahlman, Carl J. (1980), The Open Field System and Beyond, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 95

- ↑ Cox, S., (1985). "No tragedy on the commons". Environmental Ethics 7:49–61.

- ↑ Levine, Bruce (January 1986). <81::AID-JCOP2290140108>3.0.CO;2-G "The Tragedy of the Commons and the Comedy of Community: The Commons in History". Journal of Community Psychology. 14: 81–99 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ↑ "Economic Manuscripts: Capital Vol. I - Chapter Twenty-Seven". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ↑ Campbell, Bruce M. S. "The Land" in A Social History of England, 1200–1500, ed. by Rosemary Horrox and W. Mark Ormrod. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 237

- ↑ McCloskey, Donald N. (March 1972). "The Enclosure of Open Fields: Preface to a Study of Its Impact on the Efficiency of English Agriculture in the Eighteenth Century". The Journal of Economic History. 32 (1): 15–35. doi:10.1017/S0022050700075379. ISSN 0022-0507.

- ↑ McCloskey, Donald N. (1975). "2: The Persistence of English Common Fields" (PDF). In Parker, William N.; Jones, Eric L (eds.). European Peasants and Their Markets: Essays in Agrarian Economic History. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 73. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ↑ McCloskey, Donald N. (March 1972). "The Enclosure of Open Fields: Preface to a Study of Its Impact on the Efficiency of English Agriculture in the Eighteenth Century". The Journal of Economic History. 32 (1): 15–35. doi:10.1017/S0022050700075379. ISSN 0022-0507.

- ↑ McCloskey, p. 11

Further reading

- Gray, Howard L (1959) [1915]. The English Field Systems. Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press; Merlin Press.

- Rackham, Oliver (1986). The History of the Countryside. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0460044493. (On Britain, primarily England)

- Powell, Sumner Chilton (1963). Puritan Village: The Formation of a New England Town. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. (On the expansion of the open-field system into the New World)

- Hall, David (2014). The Open Fields of England. Oxford: O.U.P. ISBN 978-0-19-870295-5.

External links

- Smith, Roly (2 December 2000). "Open Society". The Guardian.

- Trent & Peak Archaeological Trust (1995). "The Laxton Village Survey".