| Herpes zoster ophthalmicus | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Ophthalmic zoster |

| |

| Herpes zoster ophthalmicus | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

| Symptoms | Rash of the forehead, swelling of the eyelid, pain and red eye |

| Complications | visual impairment, increased pressure within the eye, chronic pain, stroke |

| Causes | Reactivation of varicella zoster virus |

| Risk factors | Poor immune function, psychological stress, older age |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms |

| Prevention | Herpes zoster vaccine |

| Medication | Antiviral pills such as acyclovir, steroid eye drops |

| Frequency | Up to 125,000 per year (US)[1] |

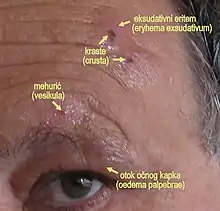

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO), also known as ophthalmic zoster, is shingles involving the eye or the surrounding area. Common signs include a rash of the forehead with swelling of the eyelid. There may also be eye pain and redness, inflammation of the conjunctiva, cornea or uvea, and sensitivity to light. Fever and tingling of the skin and allodynia near the eye may precede the rash. Complications may include visual impairment, increased pressure within the eye, chronic pain,[1][2][3] and stroke.[4]

The underlying mechanism involves a reactivation of the latent varicella zoster virus (VZV) within the trigeminal ganglion supplying the ophthalmic nerve (the first division of the trigeminal nerve). Diagnosis is generally based on signs and symptoms.[2] Alternatively, fluid collected from the rash may be analyzed for VZV DNA using real-time PCR. This test is rapid, easy to perform, and is highly sensitive and specific method for diagnosing this condition.[5]

Treatment is generally with antiviral pills such as acyclovir. Steroid eye drops and drops to dilate the pupil may also be used. The herpes zoster vaccine is recommended for prevention in those over the age of 50.[2] HZO is the second most common manifestation of shingles, the first being involvement of skin of the thorax. Shingles affects up to one half million people in the United States per year, of which 10% to 25% is HZO.[1][3]

Signs and symptoms

Skin

- Viral prodrome

- Preherpetic neuralgia

- Rash, transitioning from papules to vesicles to pustules to scabs.

- Hutchinson's sign: cutaneous involvement of the tip of the nose, indicating nasociliary nerve involvement. While a positive Hutchinson's sign increases the likelihood of ocular complications associated with HZO, it's absence does not rule out ophthalmic involvement.[6]

- Disseminated distribution in individuals with immunodeficiency.[7]

Cornea

- Epithelial: punctate epithelial erosions and pseudodendrites: often have anterior stromal infiltrates. Onset 2 to 3 days after the onset of the rash, resolving within 2–3 weeks. Common.

- Stromal:

- Nummular keratitis: have anterior stromal granular deposits. Occurs within 10 days of onset of rash. Uncommon

- Necrotising interstitial keratitis: Characterised by stromal infiltrates, corneal thinning and possibly perforation. Occurs between 3 months and several years after the onset of rash. Rare.

- Disciform Keratitis (Disciform Endotheliitis): a disc of corneal oedema, folds in Descemet's membrane, mild inflammation evident within the anterior chamber and fine keratic precipitates. Chronic. Occurs between 3 months and several years after the onset of the rash. Uncommon.

- Neurotrophic: corneal nerve damage causes a persistent epithelial defect, thinning and even perforation. The cornea becomes susceptible to bacterial and fungal keratitis. Chronic. Late onset. Uncommon.

- Mucous plaques: linear grey elevations loosely adherent to the underlying diseased epithelium/stroma. Chronic. Onset between 3 months and several years after the onset of the rash.[7]

Uveal

Anterior uveitis develops in 40–50% of people with HZO within 2 weeks of the onset of the skin rashes. Typical HZO keratitis at least mild iritis, especially if Hutchinson's sign is positive for the presence of vesicles upon the tip of the nose.

Features:[8]

This non-granulomatous iridocyclitis is associated with:

- Small keratic precipitates

- Mild aqueous flare

- Occasionally haemorrhagic hypopyon

HZO uveitis is associated with complications such as iris atrophy and secondary glaucoma are not uncommon. Complicated cataract may develop in the late stages of the disease.

Anatomy

HZO is due to reactivation of VZV within the trigeminal ganglion. The trigeminal ganglion give rise to the three divisions of cranial nerve V (CN V), namely the ophthalmic nerve, the maxillary nerve, and the mandibular nerve. VZV reactivation in trigeminal ganglion predominantly affects the ophthalmic nerve, for reasons not clearly known.[9] The ophthalmic nerve gives rise to three branches: the supraorbital nerve, the supratrochlear nerve, and the nasociliary nerve. Any combination of these nerves can be affected in HZO, although the most feared complications occur with nasociliary nerve involvement, due to its innervation of the eye. The supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves mainly innervate the skin of the forehead. The frontal nerve is more commonly affected than the nasociliary nerve or lacrimal nerve.[8]

Treatment

Treatment is usually with antivirals such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famcyclovir by mouth.[2] There is uncertainty as to the difference in effect between these three antivirals.[10] Antiviral eye drops have not been found to be useful.[1] These medications work best if started within 3 days of the start of the rash.[3]

Cycloplegics prevent synechiae from forming.

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Herpetic Corneal Infections: Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus". www.aao.org. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 "Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus - Eye Disorders". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- 1 2 3 Shaikh S, Ta CN (November 2002). "Evaluation and management of herpes zoster ophthalmicus". American Family Physician. 66 (9): 1723–30. PMID 12449270.

- ↑ Nagel MA, Gilden D (April 2015). "The relationship between herpes zoster and stroke". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 15 (4): 16. doi:10.1007/s11910-015-0534-4. PMC 5489066. PMID 25712420.

- ↑ Beards G, Graham C, Pillay D (1998). "Investigation of vesicular rashes for HSV and VZV by PCR". J. Med. Virol. 54 (3): 155–7. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199803)54:3<155::AID-JMV1>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 9515761. S2CID 24215093.

- ↑ Butsch F, Greger D, Butsch C, von Stebut E (May 2017). "Prognostic value of Hutchinson's sign for ocular involvement in herpes zoster ophthalmicus: Correspondence". JDDG: Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft. 15 (5): 563–564. doi:10.1111/ddg.13227. PMID 28422437. S2CID 205057527. Archived from the original on 2023-07-08. Retrieved 2022-09-06.

- 1 2 Denniston AK, Murray PI (2009-06-11). Oxford Handbook of Ophthalmology. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780199552641. Archived from the original on 2023-07-08. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - 1 2 Khurana AK (2008). Comprehensive Ophthalmology. Anshan. ISBN 9781905740789. Archived from the original on 2023-07-08. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ↑ Pitton Rissardo J, Fornari Caprara AL (2018-09-27). "Herpes Zoster Oticus, Ophthalmicus, and Cutaneous Disseminated: Case Report and Literature Review". Neuro-Ophthalmology. 43 (6): 407–410. doi:10.1080/01658107.2018.1523932. ISSN 0165-8107. PMC 7053943. PMID 32165902.

- ↑ Schuster AK, Harder BC, Schlichtenbrede FC, Jarczok MN, Tesarz J (November 2016). Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group (ed.). "Valacyclovir versus acyclovir for the treatment of herpes zoster ophthalmicus in immunocompetent patients". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (11): CD011503. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011503.pub2. PMC 6464932. PMID 27841441.