Oskaloosa, Iowa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname: Osky | |

| Motto: "Note the Difference" | |

Location of Oskaloosa, Iowa | |

Oskaloosa Location in the United States  Oskaloosa Oskaloosa (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 41°17′31″N 92°38′25″W / 41.29194°N 92.64028°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Mahaska |

| Incorporated | February 4, 1875[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8.04 sq mi (20.81 km2) |

| • Land | 8.02 sq mi (20.77 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.04 km2) |

| Elevation | 846 ft (258 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 11,558 |

| • Density | 1,440.97/sq mi (556.38/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 52577 |

| Area code | 641 |

| FIPS code | 19-59925 |

| GNIS feature ID | 468480[3] |

| Website | www |

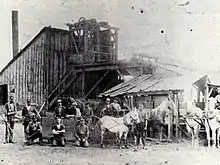

Oskaloosa is a city in, and the county seat of, Mahaska County, Iowa, United States.[4] In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Oskaloosa was a national center of bituminous coal mining. The population was 11,558 in the 2020 U.S. census.[5]

History

.jpg.webp)

Oskaloosa derives its name from Ouscaloosa who, according to town lore, was a Creek princess who married Seminole chief Osceola. A local tradition was that her name meant "last of the beautiful." (This interpretation of "last of the beautiful" is not correct. "Oskaloosa" in the Mvskoke-Creek language means "black rain," from the Mvskoke words "oske" (rain) and "lvste" (black). "loosa" is an English corruption of the Mvskoke word "lvste". See for example the Wikipedia entry for Tuskaloosa, eponym of the town of Tuscaloosa, Alabama. In addition the Mvskoke word "Ouscaloosa" means "Black Water").[6] The first European-American settlers arrived in 1835, led by Nathan Boone, youngest son of frontiersman Daniel Boone. Acting on instructions from Stephen W. Kearny, he selected this as the first site of Fort Des Moines, located on a high ridge between the Skunk and Des Moines rivers. The ridge was originally called the Narrows.

The town was formally platted in 1844 when William Canfield moved his trading post from the Des Moines River to Oskaloosa. The town was designated by the legislature as the county seat in the same year.[6]

The Des Moines Valley Railroad built north from Eddyville, Iowa through Oskaloosa to Pella, Iowa in 1864. In 1873, this became the Keokuk and Des Moines Railroad, and in 1887, it was leased by the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad.[7] The Central Iowa Railway followed, which became the Iowa Central Railway in 1888 and was absorbed by the Minneapolis and St. Louis Railway in 1901. In 1883, the Burlington and Western Railway reached Oskaloosa; this was a narrow gauge line that was widened to Standard Gauge in 1902 and then merged with the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad.[8]

On January 6, 1882, most of the buildings in the north half of Oskaloosa were severely damaged and most of the plate glass windows in the area were broken by an explosion. Three boys were killed in the explosion. The boys had been seen shooting at the A. L. Spencer gunpowder magazine half a mile north of the town center.[9]

The first bituminous coal mine in the area was opened shortly after 1853 by Robert Seevers, who drove a drift into a four-foot coalbed in an exposed creek bank east of town.[10] Initially, coal was mined entirely for local consumption, but with the arrival of the railroads, coal from the region was shipped widely. In the 1880s, more than one million tons of coal was mined in the county from 38 mines. By 1887, the report of the state mine inspector listed 11 coal mines in or very close to Oskaloosa.[11] By 1895, the coal output of Mahaska County surpassed that of all other Iowa counties, and production had reached more than one million tons per year.[12] In 1911, coal mining was reported to be the primary industry in the region.[13] In 1914, the Carbon Block Coal Company of Centerville produced more than 100,000 tons of coal, ranking among the top 24 coal producers in the state.[14]

Several major coal-mining camps were located in the Oskaloosa area. Muchakinock was approximately five miles south of town, on the banks of the Muchakinock Creek. Lost Creek was a company town and post office with a population of about 500 in 1905, located about 10 miles south of town.[15] On January 24, 1902, there was a mine explosion in the Lost Creek No. 2 mine. This was one of only two major mine disasters in Iowa between 1888 and 1913. A miner setting shots to blast coal from the coal face re-used a hole left over from a previous failed shot, and the result was a coal dust explosion that detonated barrels of gunpowder stored in the mine. Twenty men died on the site and 14 more were badly injured. The explosion sparked a statewide miner's strike. As a result, in April 1903, the legislature enacted a law to regulate blasting in coal mines.[16][17]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 7.45 square miles (19.30 km2), of which 7.43 square miles (19.24 km2) is land and 0.02 square miles (0.05 km2) is water.[18]

Climate

According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Oskaloosa has a hot-summer humid continental climate, abbreviated "Dfa" on climate maps.

| Climate data for Oskaloosa, Iowa, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 69 (21) |

78 (26) |

88 (31) |

92 (33) |

106 (41) |

104 (40) |

112 (44) |

112 (44) |

101 (38) |

96 (36) |

82 (28) |

75 (24) |

112 (44) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 53.1 (11.7) |

58.3 (14.6) |

73.1 (22.8) |

81.5 (27.5) |

86.9 (30.5) |

90.9 (32.7) |

94.5 (34.7) |

93.4 (34.1) |

90.1 (32.3) |

83.6 (28.7) |

69.2 (20.7) |

57.7 (14.3) |

96.4 (35.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 30.7 (−0.7) |

35.9 (2.2) |

49.3 (9.6) |

62.2 (16.8) |

72.2 (22.3) |

81.5 (27.5) |

85.5 (29.7) |

83.8 (28.8) |

77.4 (25.2) |

64.5 (18.1) |

49.3 (9.6) |

36.2 (2.3) |

60.7 (16.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 21.5 (−5.8) |

25.9 (−3.4) |

38.3 (3.5) |

50.1 (10.1) |

61.5 (16.4) |

71.2 (21.8) |

75.2 (24.0) |

72.9 (22.7) |

65.2 (18.4) |

52.8 (11.6) |

38.9 (3.8) |

27.2 (−2.7) |

50.1 (10.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 12.2 (−11.0) |

15.9 (−8.9) |

27.3 (−2.6) |

38.1 (3.4) |

50.8 (10.4) |

60.8 (16.0) |

64.8 (18.2) |

62.0 (16.7) |

53.0 (11.7) |

41.2 (5.1) |

28.5 (−1.9) |

18.2 (−7.7) |

39.4 (4.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −10.0 (−23.3) |

−4.4 (−20.2) |

6.7 (−14.1) |

23.0 (−5.0) |

36.0 (2.2) |

48.0 (8.9) |

54.1 (12.3) |

51.5 (10.8) |

38.0 (3.3) |

25.6 (−3.6) |

11.5 (−11.4) |

−2.4 (−19.1) |

−13.7 (−25.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −31 (−35) |

−31 (−35) |

−30 (−34) |

6 (−14) |

24 (−4) |

36 (2) |

44 (7) |

36 (2) |

20 (−7) |

3 (−16) |

−7 (−22) |

−30 (−34) |

−31 (−35) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.75 (44) |

1.74 (44) |

2.15 (55) |

3.92 (100) |

4.71 (120) |

5.18 (132) |

4.40 (112) |

5.08 (129) |

3.56 (90) |

2.68 (68) |

2.20 (56) |

1.35 (34) |

38.72 (984) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 5.6 (14) |

8.6 (22) |

3.8 (9.7) |

0.6 (1.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.8 (2.0) |

5.7 (14) |

25.1 (63.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 5.6 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 10.0 | 11.5 | 10.2 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 7.2 | 7.4 | 6.3 | 6.1 | 94.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.3 | 3.5 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 2.8 | 11.8 |

| Source 1: NOAA (average snowfall/snow days 1981–2010)[19][20] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[21] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 625 | — | |

| 1860 | 4,393 | 602.9% | |

| 1870 | 3,204 | −27.1% | |

| 1880 | 4,598 | 43.5% | |

| 1890 | 6,558 | 42.6% | |

| 1900 | 9,212 | 40.5% | |

| 1910 | 9,466 | 2.8% | |

| 1920 | 9,427 | −0.4% | |

| 1930 | 10,123 | 7.4% | |

| 1940 | 11,024 | 8.9% | |

| 1950 | 11,124 | 0.9% | |

| 1960 | 11,053 | −0.6% | |

| 1970 | 11,224 | 1.5% | |

| 1980 | 10,989 | −2.1% | |

| 1990 | 10,632 | −3.2% | |

| 2000 | 10,938 | 2.9% | |

| 2010 | 11,463 | 4.8% | |

| 2020 | 11,558 | 0.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[22][5] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[23] of 2010, there were 11,463 people, 4,715 households, and 2,842 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,542.8 inhabitants per square mile (595.7/km2). There were 5,144 housing units at an average density of 692.3 per square mile (267.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 94% White, 1.5% African American, 0.3% Native American, 1.5% Asian, 0.9% from other races, and 1.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.4% of the population.

There were 4,715 households, of which 29.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.0% were married couples living together, 12.2% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.1% had a male householder with no wife present, and 39.7% were non-families. 33.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.30 and the average family size was 2.92.

The median age in the city was 35.8 years. 23.4% of residents were under the age of 18; 13.1% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 23.3% were from 25 to 44; 23.2% were from 45 to 64; and 17.1% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.8% male and 51.2% female.

2000 census

As of the census[24] of 2000, there were 10,938 people, 4,603 households, and 2,863 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,593.8 inhabitants per square mile (615.4/km2). There were 4,945 housing units at an average density of 720.5 per square mile (278.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 96.00% White, 1.04% African American, 0.25% Native American, 1.32% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.41% from other races, and 0.94% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.26% of the population.

There were 4,603 households, out of which 29.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.2% were married couples living together, 10.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.8% were non-families. 32.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.28 and the average family size was 2.89.

Population spread: 24.1% under the age of 18, 11.2% from 18 to 24, 26.2% from 25 to 44, 19.9% from 45 to 64, and 18.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $34,490, and the median income for a family was $42,138. Males had a median income of $33,830 versus $23,698 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,721. About 10.6% of families and 13.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.0% of those under age 18 and 11.6% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Top Ten Companies

| Employer | Date Founded | Type of Business | Approximate Number of Employees | Description of Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Musco Lighting | 1976 | Sports Lighting | 450 | Provides permanent and temporary lighting for major sports venues around the world. |

| Oskaloosa Community Schools | Education | 375 | Includes a high school, middle school, elementary school, preschool and alternative school. | |

| Mahaska Health Partnership | 1907 | Healthcare Services | 450 | Offers surgical services, inpatient services, a birthing Center, and emergency services. |

| Clow Valve Company | 1878 | Manufacturing | 350 | The Oskaloosa plants include iron and brass foundries, a machine shop, assembly, finished goods warehousing, shipping and administrative offices. Their primary products include fire hydrants and a variety of valves. |

| Wal-Mart | 1962 | Retail Department Store | 265 | |

| William Penn University | 1873 | Education | 300 | A private, liberal arts university. |

| City of Oskaloosa | 1844 | Municipal Government | 199 | |

| Hy-Vee | 1930 | Retail Food Store | 155 | An employee-owned chain of supermarkets located in the Midwestern United States. |

| Cunningham Incorporated | 1969 | Mechanical Contractor-Commercial, Industrial | 100 | Sheetmetal manufacturing, HVAC, geo-thermal, plumbing-piping, architectural metal-roofing, industrial services, and duct cleaning. |

| Mahaska Bottling Company | Soft Drinks | 97 | Pepsi-Cola bottling company. |

- Source: LocationOne Information Systems website and telephone survey conducted February 2010

Oskaloosa is also the headquarters of the music publisher C.L. Barnhouse Company.

Arts and culture

Annual events

The Southern Iowa Fair is one of the largest traditional county fairs in Iowa and is held each July.

Art on the Square is held each June on the city square. This event features local and regional artists.

Sweet Corn Serenade is held each July on the city square. A concert by the municipal band is the highlight of the corn-on-the-cob and pork burger feast.

Each December, the Lighted Christmas Parade travels through the downtown area on two consecutive nights. The floats in the parade are adorned with lights for the after-dark event.

Government and politics

The City of Oskaloosa has a mayor-city council-city manager form of government under a home rule charter. The mayor and city council are elected. The city council is composed of seven members who make decisions regarding rules and regulations pertaining to Oskaloosa. The mayor is elected for a two-year term and council members are elected to serve for four years. The city manager is appointed by the city council.

Oskaloosa is a sister city with Shpola, Ukraine.

In July 2015, presidential candidate Donald Trump held a campaign event, a family picnic, at Oskaloosa's George Daily Community Auditorium. He did not give press credentials to the Des Moines Register for the event, due to its having had an editorial urging him to drop out of the race.[25]

In November 2019, presidential candidate Joe Biden held a campaign event at William Penn University.

Education

Oskaloosa is the home of William Penn University, a private, liberal arts college. It was founded by members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in 1873 as Penn College. In 1933, the name was changed to William Penn College, and finally to William Penn University in 2000.

Oskaloosa was the home of the now-defunct Oskaloosa College.

The city's public system, Oskaloosa Community School District, operates a high school, middle school, elementary school, and an alternative school. Oskaloosa Elementary opened in January 2005, merging five smaller buildings scattered across the city. The building is the largest elementary school in Iowa.

Also in Oskaloosa is Oskaloosa Christian Grade School, which was founded in 1946. SonShine Preschool was started later on and is in the same building.

Transportation

Transit services in the city are provided by Oskaloosa Rides. Free bus service is provided along one fixed-route loop in the city, on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays from 9:00 AM to 5:30 PM. Paratransit services operated by 10-15 Transit are provided daily.[26]

Distinctions

In the city's town square is a bronze statue of Chief Mahaska, the 19th-century leader of a Native American tribe called the Ioway; he was memorialized by the name of Mahaska County. Restored in the 21st century, the statue was completed in 1907 by an Iowa-born sculptor named Sherry Edmundson Fry (1879–1966). At the time it was commissioned, Fry was living in Paris. He returned to Iowa the following summer to make preparatory drawings of Meskwaki at the nearby Settlement at Tama, Iowa, and to collect Indian artifacts and other reference materials. Returning to Paris, he began on a clay scale model, which he first showed at the Paris Salon in 1907. A year later, Fry exhibited the final full-sized sculpture, for which he won the Prix de Rome. Soon after, it was shipped to the US, and arrived in Oskaloosa by railroad in September. The formal dedication of the statue was held on May 12, 1909, and attended by a crowd of about 12,000 people.

Oskaloosa boasts two private homes designed in 1948–51 by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Typical of his Usonian homes, these are the Carroll Alsop House at 1907 A Ave E and the Jack Lamberson House at 511 North Park Avenue.

Oskaloosa hosted the Iowa State Fair in 1858 and 1859, prior to the Civil War.

In 1934, Oskaloosa became the first city in the United States to fingerprint all of its citizens, including children.

Municipal Band and historic bandstand

The first settlers in the area brought along their instruments and a deep love of music. Residents organized a town band in 1864. In 1880 the band was called the K. T. Band (for Knight Templars). About 1882 the city erected a double-deck bandstand in the center of the city park. The band had started playing in the city park when it was just a field. A brick walk through the park was constructed with money raised from a local talent minstrel show. In 1886 the Knee Gahh Band went to St. Louis for their national conclave and was a tremendous hit. That marked the beginning of the band's prominence in the Midwest.

Charles L. Barnhouse developed the band "atmosphere" from the time he came to Oskaloosa in 1891. He exerted a creative influence to build up a musical organization that would become the pride of the city. His band garnered statewide acclaim, becoming the official band of the Iowa State Fair for four years. In 1904 the band played at the annual National Encampment of the Grand Army of the Republic in Louisville, Kentucky. En route, it played by invitation at the World's Fair in Saint Louis, Missouri. In the ensuing years the band became popular throughout Iowa and other states.

In 1907 and 1908 Oskaloosa had two bands playing concerts – the Iowa Brigade Band and LaRue's Band. The merchants on High Avenue West employed their own band to compete with the Iowa Brigade Band in the park on Saturday evenings.

In 1911 the citizens decided to beautify the city and voted to fund improvements for the city park. The citizens recommended a new bandstand be erected in the center of the park. The old double-deck frame bandstand was moved to one side to be used while the new bandstand was being built. The first concert in the new bandstand was played on June 1, 1912, and the bandstand was dedicated on July 25, 1912.

Notable people

- Eddie Anderson, football head coach at University of Iowa 1939–42, 1946–49

- Alfred Balk, magazine editor

- Bill S. Ballinger, author and screenwriter

- Steve Bell, former ABC News anchor

- Max Bennett, jazz musician

- Charles Brookins, track and field athlete

- Elaine Christy, harpist

- Bernard A. Clarey, Admiral, among most decorated U.S. Navy officers; Admiral Clarey Bridge in Pearl Harbor named after him

- Chester Conklin, comedian and actor

- Marsena E. Cutts, politician

- Lisa Eagen, athlete, 1996 Atlanta Summer Olympics, team handball[27]

- Dulah Marie Evans, painter, photographer, etcher

- Frank Friday Fletcher, Admiral, Medal of Honor recipient and namesake of the Fletcher-class destroyer

- Cliff Knox, Major League Baseball player

- John F. Lacey, U.S. Representative

- Tip Lamberson, flute maker

- Harry Hamilton Laughlin, eugenicist

- Lillian Miles, actress best known for her performance in the anti-marijuana film Reefer Madness

- Patrick O'Bryant, National Basketball Association player

- Arthur Russell, modern music composer

- Tyler Sash, defensive back for Iowa Hawkeyes and Super Bowl champion with the NFL's New York Giants

- Emma Steghagen, labor organizer and suffragist

- John H. Stek, translator of New International Version Bible

- Cecil W. Stoughton, Kennedy presidential photographer

- Al Swearengen, proprietor of Gem Saloon in Deadwood, South Dakota, 1877–1899 (featured in HBO series Deadwood)

- Ed Thomas, football coach[28]

- Guy Vander Linden, Iowa state representative, U.S. Marines Brigadier General

- Thomas Eugene Watson, U.S. Marines lieutenant general

- Clarence C. Wiley, ragtime music composer

- Roscoe B. Woodruff, U.S. Army general of World War II

See also

References

- ↑ "Oskaloosa, Iowa". City-Data. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ↑ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Oskaloosa, Iowa

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- 1 2 "2020 Census State Redistricting Data". census.gov. United states Census Bureau. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- 1 2 "Oskaloosa History". Community Profile Network, Inc. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ↑ Bruce Boertje, Des Moines Valley Railroad, Historic Pella Trust, April 8, 2019.

- ↑ David Lotz and Charles Franzen, 'Rails to a County Seat', The Print Shop, Washington Iowa, 1989; pages 37, 47-52.

- ↑ "The Explosion at Oskaloosa", New York Times, 7 January 1882

- ↑ Iowa Geological Survey Annual Report for 1908. Published for the Iowa Geological Survey. 1909. p. 556.

- ↑ George E., Roberts (1888). Third Biennial Report of the State Mine Inspectors to the Governor of Iowa for the years 1886 and 1887. p. 87.

- ↑ Conaway, Des Moines, 1895, Seventh Biennial Report of the State Mine Inspectors to the Governor of the State of Iowa for the two years ending June 30, 1895, page 50.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 351.

- ↑ Saward, Frederick E. (1915). The Coal Trade. p. 65.

- ↑ Iowa State Gazetteer and Business Directory, 1905-1906, Vol XIII, R. L. Polk & Co., 1905; page 893, column 2 center.

- ↑ Albert H. Fay, Coal-Mine Fatalities in the United States 1870–1914, Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines, Washington DC, 1916, page 190.

- ↑ Paul Garvin, Iowa's Minerals, Burr Oak Books, 1998, pages 198–199.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ↑ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access (1991–2020)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ↑ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access (1981–2010)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 31, 2022.

- ↑ "NOAA Online Weather Data". National Weather Service. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ Noble, Jason (July 24, 2015). "Trump barring Des Moines Register from campaign event". Des Moines Register. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Oskaloosa Rides". Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ↑ "Eagen A Humble Hero". Oskaloosa Herald. June 29, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ↑ "2,500 give final salute to coach Ed Thomas". Des Moines Register. February 10, 2010. Archived from the original on January 15, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2014.