Oxen, cows, beef cattle, buffalo and so on are an important motif in Chinese mythology. There are many myths about the oxen or ox-like beings, including both celestial and earthly varieties. The myths range from ones which include oxen or composite beings with ox characteristics as major actors to ones which focus on human or divine actors, in which the role of the oxen are more subsidiary. In some cases, Chinese myths focus on oxen-related subjects, such as plowing and agriculture or ox-powered carriage. Another important role for beef cattle is in the religious capacity of sacrificial offerings.

Terminology

The Chinese character 牛 (pinyin: niú) used for "ox" is rather non-specific. It can refer to a male, castrate or not, or to a female, young or old, of various species of the bovine family which have been domesticated for use as draft animals, with their strength being harnessed for various purposes, especially carting loads and various types of farm work, such as plowing. Niú also can be construed as singular or plural. However, male cattle used for hard labor are often castrated in order to make them more tractable, as well as providing better quality meat when finally consumed.

Background

Myth versus history

In the study of historical Chinese culture and other ethnic cultures in the area of what is now China, many of the stories that have been or are told regarding various characters and events have a double tradition: one of which traditions presents a more historicized version and a more rationalized account, and, another version which presents a more mythological and perhaps fantastic account (Yang 2005:12–13). This is also true of the accounts involving to mythological bovids.

Bovids

Oxen, in some cases, are real creatures, of the bovine subfamily. Some have been domesticated, and used in China (or what is now China), for several millennia, doing such tasks as related to agriculture, hauling, or other applications requiring great strength. Despite the use of mechanical innovations such tractors and other modern machinery, the ox has not been totally replaced, and many areas still follow traditional methods, and tell variations of traditional myths involving oxen.

Taxonomy

The family Bovidae includes almost 140 species of cloven-hoofed, ruminant mammals with characteristic unbranching horns covered in a permanent sheath of keratin in at least the males, but in terms of domestic cattle in China, this widespread family tends to be represented by the genus Bos in the north, similar to the familiar European and American domestic cattle; the Bubalus ("water buffalo"), generally in the warmer and wetter areas of the south, such as the Yangzi River valley; and, the yak (also in the genus Bos), in the higher and colder elevations of the more westward regions. There were many crosses between the various types, including with the zebu (taxonomically another Bos), and many specialized breeds developed over the millennia.

Agriculture

.jpg.webp)

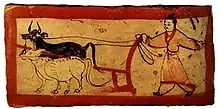

Various types of oxen have been domesticated in the area of what is now modern China for thousands of years, used for agriculture, transportation, for food, and other purposes. These generally powerful creatures have had a significant roles in turning and tilling the soil with the plow, hauling loads by pulling an oxcart, turning millstones and waterwheels, and in the case of the yak, being saddled and ridden by humans or carrying loads mounted on their backs. The water buffalo also is ridden, though in a more bareback style. Sometimes the animals are raced for sport, or otherwise used for entertainment. The use of ox dung has had an important role both as a fertilizer and as fuel. Horns, bones, and hides of oxen have been employed for many purposes. Horns to make spoons and cups, bones for various purposes, and hides for leather. Many myths and religious beliefs have arisen around these various types of oxen during this multimillennial interaction between humans and oxen.

Chinese mythology

Chinese mythology refers to those myths found in the historical geographic area of China.[note 1] This includes myths in Chinese and other languages, as transmitted by Han Chinese as well as other ethnic groups (of which fifty-six are officially recognized by the current administration of China) (Yang 2005:4). Various motifs of oxen exist in Chinese mythology. In some cases the focus of the motif is on an ox or oxen as the protagonist of the action, in other cases they appear in a supporting role, sometimes as the locomotive power propelling a cart, wagon, a plow, or providing the rotary power to turn a grindstone or millwheel.

Ox star(s)

The Chinese ox star (or constellation) corresponds more-or-less with the constellation Capricornus. The Ox mansion (牛宿, pinyin: Niú Xiù) is one of the Twenty-eight mansions of the Chinese constellations. It is one of the northern mansions of the Black Tortoise. The determinative star is beta Capricorni (β Capricorni), known as 牛宿一 (Niú Su yī, literally, the First Star of Ox); or, rather, β Capricorni appears to be a star, to the naked eye, but actually resolves into double star systems, according to modern astronomy, and even with just slight magnification appears to be a double star.

Ox-Herd and Weaver-Girl

One of the myths involving the interaction of humans or divine beings and oxen is related to a popular holiday held on the 7th day of the 7th lunar month. In Chinese mythology, there is a love story of Qi Xi (七夕 literally, "the Seventh Night"), in which Niulang (the Cow-Herd) (牛郎, Altair) and his two children (β and γ Aquilae) are separated from their mother Zhinü (the Weaver-Girl) (織女, lit. "Weaving Girl", Vega) who is on the far side of the river, the Milky Way. Niulang was very upset when he found his wife was taken back to heaven. Upset by the separation, the ox saw this happens and became a boat for Niulang to carry his children up to Heaven. The ox actually was once the god of cattle, but downgraded as he had violated the law of Heaven. Niulang once saved the ox when it was sick.

However, one day per year, on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month, magpies make a bridge so that Niu Lang and Zhi Nü can be together again for a brief encounter. This is the explanatory myth behind one of the major Chinese holiday festivals, sometimes known as "Chinese Valentines Day" or Qixi Festival - two of its many names.

Zodiacal ox

The "Chinese zodiac" consists of a twelve-year cycle, each year being associated with a certain creature. The second in the cycle is the Ox. One account is that the order of the beings-of-the-year is due to their order in completing a contest of racing across a river, in the so-called Great Race: the race being to determine which creatures, in which order, would be the namesakes of the twelve-year cycle. The race was run, and swum, the finishing line being across a great river. The Rat and the Ox crossed easily enough, the Ox due to being large and powerful and adept both on land and in water: the Rat asked the good-natured Ox for a ride on its back, but then ungratefully jumped off at the last minute to cross the finish line first. This is told to explain why the Rat and the Ox do not get along together.

List of ox years, with accompanying signs

The Year of the Ox is denoted by the Earthly Branch character 丑. In the Vietnamese zodiac, the water buffalo occupies the position of the Ox. The 12 animal years vary according to a biquinary year change cycle, which varies according to the 5 elemental changes as well as varying by the 2 yin and yang states. The 1961 – 1962 Year of the Ox is a Yin Metal Ox Year: as the cycle repeats itself every 60 years, so is the 2021 – 2022 Year.

- 31 January 1889 – 20 January 1890: Earth Ox

- 19 February 1901 – 7 February 1902: Metal Ox

- 6 February 1913 – 25 January 1914: Water Ox

- 24 January 1925 – 12 February 1926: Wood Ox

- 11 February 1937 – 30 January 1938: Fire Ox

- 29 January 1949 – 16 February 1950: Earth Ox

- 15 February 1961 – 4 February 1962: Metal Ox

- 3 February 1973 – 22 January 1974: Water Ox

- 20 February 1985 – 8 February 1986: Wood Ox

- 7 February 1997 – 27 January 1998: Fire Ox

- 26 January 2009 – 13 February 2010: Earth Ox

- 12 February 2021 – 31 January 2022: Metal Ox

- 31 January 2033 – 18 February 2034: Water Ox

How the Heavenly Oxen came to Earth

According to a myth told by Chinese peasants, the original plow-oxen lived in Heaven, as the Ox stars. However, the Emperor of Heaven, taking pity on the starving people of the Earth, and wishing to help them, sent the Oxen with the message that if they worked hard, they would starve no more, and that they could be sure to have a meal at least every three days. The Oxen got the message mixed-up, and instead told the people that the Emperor of Heaven promised them that if they worked hard, that they would be able to eat three times a day. This put the Emperor of Heaven in a bit of a predicament, since the people on their own would not be able to accomplish this. Therefore, to punish the oxen for getting the message wrong, and not to appear himself to be a liar, he restricted the Oxen to the Earth, where they became regular oxen, working the farms helping the people of Earth with their farm work.[1]

Shujun

Shujun is a Chinese god of farming and cultivation, also known as Yijun and Shangjun. Alternatively he is a legendary culture hero of ancient times, who was in the family tree of ancient Chinese emperors descended from the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi). Either way, Shujun is considered to be a relative of Di Jun and Houji, and a minister of Yellow Emperor. Shujun is specially credited with inventing the agricultural practice of using a draft animal of the bovine family to pull a plow to cultivate the soil prior to planting, loosening and turning it, thus greatly enhancing agricultural productivity, and then teaching this skill to others (Yang, 2005: p. 201).

Hai

Hai is also said to have been the first to have domesticated the cow and invented the oxcart. (Yang (2005), p. 70).

Composite ox beings

Various creatures, including legendary people and mythical creatures have some ox features which contribute to the parts out of which they are constituted. These include the Ox-Head guardians of Hell, the partially ox-featured god and mythological figure Chiyou, and others.

Ox-Heads

Ox-Head (simplified Chinese: 牛头; traditional Chinese: 牛頭; pinyin: niú tóu) and Horse-Face (simplified Chinese: 马面; traditional Chinese: 馬面; pinyin: mǎ miàn) are two fearsome guardians or types guardian of the Underworld in Chinese mythology, where the dead face suffering prior to reincarnation. As indicated by their names, Ox-head has the head of an ox, and Horse-face has the face of a horse. They are the first people a dead soul meets upon arriving in the Underworld; in many stories they directly escort the newly dead to the Underworld.

Chiyou

Chiyou was a war god and inventor of weapons, descended from Yan Di. Some sources describe him as being ox-headed. Lihui Yang describes Chiyou as having a six-handed human body, horned, four-eyed head with swords and spears for ears and temples, and ox hooves (2005: p. 92).

Taiyuan

In the villages of Taiyuan, sacrificing the head of an ox to Chiyou is considered improper, because he was ox-headed himself (Yang, 2005: p. 93).

Miao

Some Miao people consider Chiyou to be their ancestor. They worship oxen, which they consider to be lucky and heroic, and protective bringers of prosperity, and they wear ox horn motifs embroidered on their clothes or decorated on silver ornaments (Yang, 2005: p. 93).

Totemic ancestors

According to their mythology, as recorded in Chinese sources, the Kyrgyz people[note 2] who were red-haired and had white faces claimed to be the descendants of a mating in a mountain cave between a cow and a god (Schafer, 1963: p. 73).

Religious Sacrifice

An important role of cattle was in the capacity of serving as a religious sacrifice. An animal or animals would be ceremoniously slaughtered as a presentation to one or more deities or ancestral spirits. A portion of the sacrificial remains would be dedicated to these, and the rest generally would be distributed to the human participants of the ceremony, and eaten. Special dwarf breeds specially for this purpose seem to have existed during the Zhou dynasty: one type being the "millet ox", 稷牛 (Schafer, 1963: pp. 73, 298, 376).

Sacrificial tradition was probably the root of the Chinese New Year ceremony of "beating the Spring Ox" 打春牛. The last, together with its spirit driver Mangshen 芒神, was made of clay and consequentially whipped and smashed to pieces, as a symbol of instigation of the spring agricultural growth. Spring Ox is one of the usual motifs of the New Year pictures and agricultural almanacs.

Tang exotica

During the Tang dynasty, it was reported that the natives of Kucha (now part of Xinjiang), as part of their New Years ceremonies, would utilize fighting oxen (and other fighting animals) in order to foretell whether and how much their herds would increase or decrease during the course of the ensuing year (Schafer, 1963: p. 73–74).

Origin of earthquakes

According to a widespread Gansu province myth, earthquakes have their origin in the annoyed shrugging of the ox which bears the earth on its back (Yang, 2005: 178).

Symbolism in art

Ox herdboys riding oxen have been used as a motif in painting and graphic arts to symbolize the ability of the mind to control the body. That is, philosophically, symbolizing the ability of intellectual will to rule bodily strength and its physical urges.

Quotes

- "Since antiquity the Chinese had had many varieties of oxen, including fantastic races with motley hides, developed for the manifold sacrifices to the archaic gods" — Edward H. Schafer (1963), p. 73.

See also

- More General

- More specific

- Agriculture in Chinese mythology

- Fangfeng: ox-eared

Notes

- ↑ The geographic area of "China" is a concept which has evolved or changed though history.

- ↑ See also: Yenisei Kyrgyz

References

Citations

- ↑ Christie, 1968: pp. 91–92

Sources

- Christie, Anthony (1968). Chinese Mythology. Feltham: Hamlyn Publishing. ISBN 0600006379.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1963) The Golden Peaches of Samarkand. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05462-2.

- Yang, Lihui, et al. (2005). Handbook of Chinese Mythology. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533263-6