| Patrol Forces Southwest Asia | |

|---|---|

PATFORSWA Unit Crest | |

| Active |

|

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Part of |

|

| Main Operating Base | Naval Support Activity Bahrain, Bahrain |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | Commodore John McTamney IV |

| Command Master Chief | CMDCM James Murray |

Patrol Forces Southwest Asia (PATFORSWA) is a United States Coast Guard command based in Manama, Bahrain. PATFORSWA was created in November 2002 as a contingency operation to support the U.S. Navy with patrol boats. The command's mission is to train, equip, deploy, and support combat-ready Coast Guard forces conducting operations in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) in the Naval Forces Central Command's area of responsibility.[1] It was commissioned as a permanent duty station in June 2004.[2] In July 2003, PATFORSWA moved from its own compound to facilities at Naval Support Activity Bahrain.[3][4]

Elements

PATFORSWA consists of three distinct elements: six 154-foot Sentinel-class cutters, Shoreside Support, and the Maritime Engagement Team.[5]

Mission

- Deter Iran

- Building partnerships

- Deter smuggling

- Counter piracy

Cutters

The six Sentinel-class cutters, CGC Charles Moulthrope, CGC Robert Goldman, CGC Glen Harris, CGC Emlen Tunnell, CGC John Scheuerman, and CGC Clarence Sutphin Jr are homeported in Bahrain and rely on Shoreside Support for maintenance, logistics, and more.

Shoreside Support

The Shoreside Support comprises a headquarters element, logistics/supply, maintenance/repair, information/electronics, and armory staff. Today, the shoreside staff numbers roughly 125 enlisted and 14 officers and is headed by an O-6 Commodore. Members aid the cutters in routine maintenance, support critical repairs, facilitate the shipping and receiving of parts, enable the movement of personnel, and liaise with Navy leadership. The diverse requirements of the unit make it unique within the Coast Guard, fulfilling elements of a CG Sector, a CG Base, and other CG staff elements.

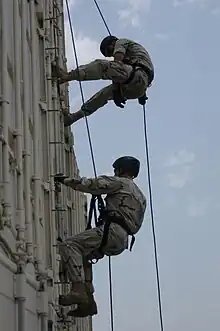

Maritime Engagement Team

The Maritime Engagement Team (MET) is responsible for providing specialized law enforcement training to all cutters in theater and certifying their Level II Non-Compliant Boarding Teams. PATFORSWA operates under Title 10 authorities; personnel maintain standard law enforcement qualifications with additional training tailored to the region.

The MET supports shipboard Visit, Board, Search, and Seizure (VBSS) training at their state-of-the-art training center and conducts subject matter expert exchanges with U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and international partners. The MET travels to participate in broader exercises with regional partners and is the VBSS training center in the Middle East. The interactions with DoD and international partners are key to the MET’s mission to build maritime enforcement capacity while strengthening international relations.[2]

Unit History

2002 Establishment

Initial preparations for naval operations supporting OIF began with the U.S. Navy in the summer and fall of 2002. The navy drew upon its standing contingency plans for combat operations involving Iraq and, in September 2002, United States Naval Forces Central Command (NAVCENT) requested U.S. Coast Guard support for a mission termed “Operation Iraqi Freedom.” The Navy saw the Coast Guard's cutters and skilled personnel as ideally suited to naval operations supporting Operation Iraqi Freedom. The shallow coastal areas and waterways of Iraq are subject to heavy silting and strategists believed that Iraq's primary threat to American naval units came from small boats, patrol craft and mine laying vessels. The Coast Guard's patrol boats would expand the naval presence to shallow littoral areas where larger naval combatants could not navigate and Coast Guard cutters could remain on station for days as opposed to only a few hours typical of the Navy's Special Forces boats. In addition, the law enforcement background of Coast Guard personnel would expand the Navy's ability to intercept and board Iraqi vessels and Coast Guard cutters could serve in force protection and escort duty, thereby freeing naval assets to conduct offensive combat operations.[6] Such naval integration of Coast Guard forces relied upon lessons learned during Vietnam with the deployment of Coast Guard Squadron One and the end of the Cold War with Patrol Boat Squadrons Two and Four.[7]

The Navy called on the Coast Guard to perform missions that have always formed part of the service's peace-time mission. The Navy had very limited capability in boarding, maritime interdiction and even environmental protection and yet operations in Iraq would require units trained in these operations. As a result, the Coast Guard's Port Security Units (PSUs), Law Enforcement Detachments (LEDETs), National Strike Force (NSF), cutters and a variety of other units and personnel deployed overseas to support military operations in OIF. These units included cutters assigned to provide escort and force protection to battle groups and Military Sealift Command (MSC) convoys passing from the Strait of Gibraltar to the eastern Mediterranean.

As it had in previous American combat operations, the Coast Guard conducted operations well suited to cutters and their crews. The maritime conditions of Iraq and the Persian Gulf can greatly limit the operations of most naval vessels and warships. U.S.-led coalition forces that allied against the Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein included Gulf-based nations that had their own coast guard forces. However, these particular coalition forces dedicated the use of their smaller vessels to protecting Kuwait, rather than operations in Iraqi territorial waters. Due to this and the Coast Guard's expertise in littoral and shallow-water operations, a large part of the request by United States Central Command (CENTCOM) centered on the Coast Guard's smaller patrol boats. Although various Coast Guard units and personnel had served in Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm in the 1990s, deployment of the service's Island-class patrol boats overseas would represent the first combat deployment of Coast Guard patrol boats since the Vietnam War.[8][9]

Even though the Coast Guard served a similar mission in Vietnam, there existed no operational plan to provide guidance for OIF planning and preparations. The Coast Guard began its earliest preparations in the final months of 2002 and the lack of any pre-existing plan or blueprint for this sort of mission proved the Coast Guard's greatest challenge. The service's Atlantic Area Command (LANTAREA), headquartered in Portsmouth, Virginia, created a shore detachment to support its cutter operations overseas. These patrol forces detachments would oversee all aspects of operational support, including cutter maintenance and crew rotation. In October, LANTAREA created a shore detachment to oversee personnel, supply and maintenance requirements for patrol boat operations in the Persian Gulf. It designated this detachment as Patrol Forces, Southwest Asia (PATFORSWA). LANTAREA assigned a commanding officer of PATFORSWA and selected four 110-foot Island-class patrol boats (WPBs) for the mission based on their superior maintenance records. These WPBs included Adak, Aquidneck, Baranof, and Wrangell.[10] LANTAREA created a second shore detachment for patrol boat operations in the Mediterranean; designated it Patrol Forces, Mediterranean (PATFORMED); and selected four more patrol boats for Mediterranean service. These WPBs included Bainbridge Island, Grand Isle, Knight Island and Pea Island.[7]

2003 Lieutenant Holly Harrison

In the evening of Thursday, March 20, OIF combat operations began as coalition warships launched Tomahawk missiles toward Baghdad. Aquidneck patrolled around the Naval vessels during launch operations to screen them from intruders. The missile launches proved an awesome sight and none of the off-watch crew could sleep. Harrison was unaware of the fact that, as captain of Aquidneck, she had become the first woman to command a Coast Guard cutter in a combat zone.[11] [12] [13] Aquidneck joined an escort detailed to protect coalition minesweeping vessels clearing the channel to the Iraqi port of Umm Qasr. To do this, Aquidneck and the other escorts had to navigate upstream of the minesweepers. This mission proved to be a stressful one because Harrison’s crew knew they were sailing through unswept waters and that their thin-skinned cutter would be torn apart by a floating mine. This mission concluded successfully with no casualties to the minesweepers or their escorts, but later analysis indicated that Aquidneck had passed through waters holding active mines.

Aquidneck performed numerous patrol missions to safeguard Iraqi oil platforms. On several of these patrols, Iranian gunboats would appear, test Harrison and her crew’s reactions, and gauge the capabilities of Aquidneck. Harrison drew a fine line between responding assertively and avoiding hostilities. She chose the middle ground of having the crew ready to man the cutter’s loaded guns without aiming weapons at the Iranians. Whenever Iranian vessels appeared in the cutter's patrol area, Harrison paralleled their course and matched their speed, sometimes exceeding 35 miles per hour to do so. Harrison made sure her cutter did not present a threatening posture, but she never backed down and the Iranians routinely broke off the encounters and retreated to their territorial waters. During these operations, a boarding team from Aquidneck discovered military supplies within the hulk of a tanker, including Iraqi military uniforms, money, AK-47s, fresh food and drawings of coalition naval vessels. Aquidneck's shore parties also secured several coastal bunkers that proved inaccessible to land forces.

Under Harrison’s command, Aquidneck and her dedicated crew conducted innumerable maritime interdiction, search and rescue, escort, and combat-related operations in the Northern Persian Gulf. In 2003, Harrison received recognition for these achievements, becoming the first woman in service history to receive the Bronze Star Medal in addition to her record as the first woman to command a Coast Guard cutter in combat. [14]

2003 USCGC Walnut deployment

USCGC Walnut deployed to the Arabian Gulf from Dec 2002 to Jun 2003 in support of U.S. and Coalition forces in Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. During their six month deployment, Walnut crewmembers enforced UN sanctions against Iraq, provided logistical support for captured off-shore oil platforms, and, most importantly, established a navigational channel in Khawr Abd Allah waterway leading to the port of Umm Qasr in Iraq. Walnut surveyed 40 miles of recently mine-swept waterway and removed decrepit and off-station aids to navigation. Using 35 warehoused Iraqi buoys, Walnut placed aids to mark the important channel, allowing the large amounts of military and humanitarian supplies needed to pass through to Iraq.[15]

In 2004, two additional WPBs, Monomoy and Maui, were brought to the PATFORSWA fleet for a total number of six Coast Guard Patrol Boats in the Persian Gulf.[16]

2003 Redeployment Assistance Inspection Detachments

Redeployment Assistance Inspection Detachments (RAID) consisted of Coast Guardsmen deployed with the U.S Army to support the shipment of materials in and out of war zones. Their mission was to assist the Department of Defense with the safe re-deployment of containerized cargo as well as the storage and segregation of hazardous materials. The Coast Guard's goal was to ensure that hazardous material was properly prepared for shipment and re-entry to U.S. ports. The team moved between Forward Operating Bases, making them among the few Coast Guardsmen to have been so far forward with the U.S. Army in a combat zone.[17][18]

The first RAID was deployed in 2003 and they were brought under the PATFORSWA command structure in 2010. The RAID was demobilized in May 2015.[19]

2003 PATFORMED

2003 - The Coast Guard deployed its PATFORMED patrol boats in similar fashion to the PATFORSWA 110s. WPBs Bainbridge Island, Grand Isle, Knight Island and Pea Island arrived at Augusta Bay, Sicily, after a one-month transit on board BBC Spain. It took a monumental effort by PATFORMED support staff to prepare for patrol boat operations in the Mediterranean because no Coast Guard infrastructure existed in the region.[7]

In the Mediterranean, Coast Guard operations supported naval and Military Sealift Command operations in the region. During combat operations in the Persian Gulf, PATFORMED patrol boats supported naval operations in the Mediterranean. The WPB's primary mission had been to escort U.S. Navy supply vessels and Military Sealift Command ships out of Souda Bay, Crete, the eastern Mediterranean's logistics port for American and NATO forces. The naval command cancelled this mission when Turkey would not support the use of its territory for supplying a northern front in Iraq. The four cutters then came under the operational command of the Navy's Task Force 60 for Leadership Interdiction Operations (LIO) in the eastern Mediterranean. This mission required the cutters to cut off a waterborne escape route for Iraqi leaders fleeing through Syria and into the Mediterranean. Syria, however, agreed to seal its borders, cutting off the escape route through its territory to the Mediterranean coast. Shortly after Syria closed its borders, the Sixth Fleet released the PATFORMED cutters from operations in the Mediterranean, the cutters then returned to United States by 2004.

2004 DC3 Bruckenthal

.jpg.webp)

On 24 April 2004, Damage Controlman Third Class Nathan Bruckenthal, USCG, and two U.S. Navy Sailors - Petty Officer 1st Class Michael Pernaselli and Petty Officer 2nd Class Christopher Watts, were killed while boarding a dhow that was approaching the Khawr Al Amaya oil terminal.

The service members were part of a seven-man visit, board, search and seizure (VBSS) team from USS Firebolt, a 174-foot Cyclone-class coastal patrol boat conducting missions in the Northern Arabian Gulf in support of OIF. Other members of the team, three Navy Sailors and one Coast Guardsman, were injured but survived the attack.

Bruckenthal is the first Coast Guardsman to be killed in combat since the Vietnam War and the only to die in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom.

As the Firebolt's rigid -hulled inflatable boat (RHIB) pulled alongside the dhow, a suicide bomber onboard the dhow set off explosives. The blast flipped the RHIB and threw its team into the water. The attack alerted other forces in the area to what was a coordinated attack on Iraq's oil terminals in the Gulf and prevented further loss of life and irreparable damages.

Petty Officer Pernaselli, from Monroe, New York, was 27 when he died. He is survived by his two daughters, Nicole and Dominique, his father John and mother Kathy.

Petty Officer Watts, from Knoxville, Tennessee, was 28. He is survived by his son Jacob, his father Bill and mother Brenda.

Petty Officer Bruckenthal, from Smithtown, New York, the youngest of the three, was 24. His wife of two years was pregnant with their first child when he was killed. He is survived by his daughter Natalie, his wife Pattie, his father Eric, his mother Laurie Bullock, his sister Noabeth, and his brothers Matthew and Michael.

Upon the family's request, PATFORSWA hosts a memorial service to honor and remember the fallen shipmates and the sacrifice they made every year since.[20][21]

July 25, 2018 - The Coast Guard commissioned the 28th fast response cutter (FRC) (Sentinel-class cutter), USCGC Nathan Bruckenthal, in Alexandria, Virginia in honor of Bruckenthal.[22]

February 23, 2022 - USS Firebolt decommissioned. The nearly 27-year-old ship was one of 10 patrol craft currently forward-deployed to the Middle East in support of regional maritime security operations. Firebolt commissioned in June 1995 and began conducting routine coastal patrol operations under U.S. 5th Fleet in 2003.[23]

2016 U.S. Iran Naval Incident

Referred to as the 2016 U.S.–Iran naval incident. PATFORSWA played an integral role in the rescue of the U.S. Navy Sailors. On 12 January 2016, two United States Navy riverine command boats (RCBs) cruising from Kuwait to Bahrain with a combined crew of nine men and one woman on board strayed into Iranian territorial waters[24] which extend three nautical miles around Farsi Island in the Persian Gulf. Patrol craft of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Navy seized the craft and detained the crew at a military base on Farsi Island.

According to military sources, the two RCBs were on a routine transit from Kuwait to Bahrain, which serves as the home port for Task Force 56 under the Fifth Fleet. They left Kuwait at 12:23 p.m local time and were scheduled to refuel with the U.S. Coast Guard Island Class Patrol Cutter MONOMOY at 5 p.m. During the transit one RCB developed an engine problem, and both boats stopped to solve the mechanical issue. During this time they drifted into Iranian waters. At 5:10 p.m. the boats were approached by the two small Iranian center-console craft followed by two more boats. There was a verbal exchange between the Iranian and U.S personnel and the officer commanding the RCBs allowed the Iranian sailors to come aboard and take control. The Iranian forces made the sailors kneel with their hands behind their heads. The RCBs reported their engine failure to Task Force 56, and all communications were terminated after the report. A U.S. search-and-rescue effort was launched leading to "robust bridge-to-bridge communications" with Iranian military vessels, wherein the Iranians informed U.S. Navy cruiser Anzio at 5:15 p.m that “the RCBs and their crew were in Iranian custody at Farsi Island and were safe and healthy.” By the time a search-and-rescue effort got under way (it included sending a U.S. Navy and U.S. Coast Guard vessel inside Iranian territorial waters over concern U.S. sailors could have been lost overboard), the sailors were already ashore.[25]

Secretary of State John Kerry, spoke with Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif at least five times by telephone. Kerry stated that in his other phone calls about the situation he "made it crystal clear" how serious it was and that "it was imperative to get it resolved." The sailors had a brief verbal exchange with the Iranian military and were released unharmed along with all their equipment the next day on 13 January after 15 hours, and they departed the island at 08:43 GMT on their boats. They later were escorted by a U.S. Coast Guard patrol cutter, while the U.S. Navy overwatched and supported. The Pentagon oversaw the escort on high alert.

The IRGC stated that they released the sailors after their investigation concluded the “illegal entry into Iranian water was not the result of a purposeful act.”[26]

United States Central Command stated, "A post-recovery inventory of the boats found that all weapons, ammunition and communication gear are accounted for minus two SIM Cards that appear to have been removed from two handheld satellite phones." The statement did not account for navigation equipment. A Navy command investigation continues and more details will be provided when it is completed.[25]

The U.S. Navy disciplined and/or reprimanded nine of the sailors involved in the incident, ranging from higher commanders to sailors present on the boats.[27][28]

2018 Syrian missile strike

During the 2018 Syrian missile strike, Patrol Forces Southwest Asia supported the action with the deployment of Adak and Aquidneck. The two patrol boats joined the HIGGINS Surface Action Group, that subsequently launched 23 Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles against chemical weapons sites in Syria. Higgins, Adak, and Aquidneck previously worked together at the beginning of Operation Iraqi Freedom—also for TLAM strikes.[29]

2020 Suleimani Strike

During the 2020 strike which killed IRGC Quds Force General Suleimani, PATFORSWA cutters took station in the Arabian Gulf while the shoreside and headquarters elements relocated pending the Iranian response. The unit remained on stand-by for whatever duties might prove necessary throughout the weeks following the strike.

2021 Cutter Change

In 2021 the squadron commenced the most drastic change since the unit’s conception, decommissioning the aging 110’ WPBs and bringing in the 154’ WPC Fast Response Cutters. The first two replacement cutters, Charles Moulthrope and Robert Goldman arrived at their new homeport on 25 May 2021 to replace the cutters Adak and Aquidneck, which were subsequently decommissioned on 15 June 2021.The next two replacement cutters Glen Harris and Emlen Tunnell sailed for Bahrain before the end of 2021, arriving in March of 2022, shortly before the cutters Maui, Monomoy and Wrangell were decommissioned on 22 March 2022.The cutters John Scheuerman and Clarence Sutphin Jr arrived in Bahrain on 23 August 2022 and the final 110’ WPB in theater, Baranof, was decommissioned on 26 September 2022.[30][31][32]

The swap, renewing the USCG investment in the region and America’s commitment to support regional allies, coincided with a new mission focus on counter smuggling stretching beyond the Arabian Gulf. The new cutters brought new capabilities which the Navy was quick to recognize and employ. Cutters patrol the waters of the Gulf of Oman and Northern Arabian Sea, remaining on patrol of weeks and covering thousands of miles. Their crews quickly saw success, leveraging their experience in fisheries and counter drug enforcement to interdict numerous shipments of narcotics including hashish, heroin, methamphetamine, and captagon, as well as 170 tons of explosive precursor material.[33][34][35][36][37]

Concurrently, the cutters participate in multinational exercises and engagements, building relationships and interoperability with regional partners. The cutters routinely sail alongside ships from The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and more. In fall of 2022, cutters Charles Moulthrope and Emlen Tunnell conducted a port visit and engagement in Karachi, Pakistan. Later that year cutters operated as part of the multi-national maritime force operating off Qatar during the World Cup. In spring of 2023 the cutters participated in the International Maritime Exercise 23, the largest exercise in the region.

2021 Afghanistan Withdrawal / Operation Allies Refuge

During the 2021 withdrawal from Afghanistan and subsequent humanitarian evacuation, PATFORSWA personnel integrated in the crisis response system. Shoreside Support assisted individuals being evacuated from Afghanistan.[38][39]

2023 Technological Forefront

In 2023 PATFORSWA cutters have been on the cutting edge of technological progress, working alongside Fifth Fleet’s Task Force 59 developing unmanned and artificial intelligence (AI)-powered systems. During Digital Horizon 22 the cutters successfully integrated key hardware, including employment of the Flexrotor vertical take-off and landing drone aircraft. In April of 2023, cutters sailed the Strait of Hormuz alongside the Arabian Fox unmanned surface vessel, demonstrating capability and developing operational employment models for the new technology. PATFORSWA continues to maintain a close working relationship with Task Force 59.[40][41][42]

Evolving mission

Throughout the 20 years since PATFORSWA establishment, the cutters performed a variety of missions in and around the Arabian Gulf. As the war in Iraq ebbed and shifted, the cutter mission expanded from a focus on protecting maritime infrastructure in Iraq to more broadly protecting free commerce in the Arabian Gulf, countering malign actors in the region, and building regional partnerships. Cutters routinely patrolled the entire Arabian Gulf and participating in international exercises in the area. Recognized for their adept ability to counter small combatants, they were the ideal platform to escort vessels through the Strait of Hormuz. Throughout this period the cutters worked closely with the Navy Coastal Patrol Craft (PCs) also stationed in Bahrain. This force of small combatants was routinely on the frontline against the unsafe and unprofessional interactions with the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy.[43][44][45]

See also

References

- ↑ "Patrol Forces Southwest Asia". www.atlanticarea.uscg.mil. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

The Mission of PATFORSWA is to train, organize, equip, support and deploy combat-ready Coast Guard Forces in support of CENTCOM and national security objectives.

- 1 2 http://www.uscg.mil/psc/epm/PATFORSWA.asp PSC: Enlisted Personnel Management

- ↑ DHS, USCG (26 December 2023). "Department of Homeland Security U.S. Coast Guard Budget Overview Fiscal Year 2021 Congressional Justification" (PDF). DHS.gov. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ↑ "The mission of Coast Guard Patrol Forces Southwest Asia". DVIDS. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ↑ "Departments". www.atlanticarea.uscg.mil. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ "Patrol Forces Southwest Asia (PATFORSWA)". www.atlanticarea.uscg.mil. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- 1 2 3 Thiesen, William H. (11 June 2009). "Guardians of the Gulf: A History of Coast Guard Combat Operations in Support of Operation Iraqi Freedom, 2002-2004" (PDF). media.defense.gov. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ↑ vietnamwar50th.com (26 December 2023). "The Coast Guard in the Vietnam War Part 1 of 3" (PDF). vietnamwar50th.com. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "The Long Blue Line: The Coast Guard in Vietnam-a remembrance". United States Coast Guard. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ↑ "The Long Blue Line - 20 Years OIF: "Tip of the Spear" Coast Guard Cutter Adak combat opera". United States Coast Guard. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ "The Long Blue Line - 20 Years OIF: Holly Harrison—Operation Iraqi Freedom Combat Veteran a". United States Coast Guard. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ Oviedo de Valeria, Jenny (2 August 1994). "chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/http://www.revista-educacion-matematica.org.mx/descargas/vol6/vol6-2/vol6-2-5.pdf". Educación matemática. 6 (2): 73–86. doi:10.24844/em0602.06. ISSN 2448-8089.

- ↑ "Holly R. Harrison Collection". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ "Women in Coast Guard: Historical Chronology". www.history.uscg.mil. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ "United States Coast Guard Atlantic Area > Our Organization > District 8 > District Units > Cutters > CGC WALNUT > History". www.atlanticarea.uscg.mil. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ "The Long Blue Line - 20 Years OIF: PATFORSWA—largest USCG unit outside U.S. territory". United States Coast Guard. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ "RAID Team - Coast Guard". afghanwarnews.info. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ↑ "The Coast Guard raids Afghanistan: a look at the RAID Team and what it does". DVIDS. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ Myers, Meghann (30 May 2015). "Last Coastie RAID team returns from Afghanistan". Navy Times. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ↑ "170424-N-WN521-002". www.cusnc.navy.mil. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ Roth, Dawson (24 April 2019). "www.cusnc.navy.mil/Media/Photos/igphoto/2002120059/". cusnc.navy.mil. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ "Coast Guard Commissions 28th Fast Response Cutter". www.dcms.uscg.mil. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ "Firebolt Crew Marks End of Ship's U.S. Navy Service at Decommissioning". United States Navy. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ Browne, Barbara Starr,Ryan (14 January 2016). "Ash Carter: 'Navigational error' behind U.S. sailors ending up in Iran | CNN Politics". CNN. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 "Jan. 18: U.S. Central Command statement on events surrounding Iranian detainment of 10 U.S". U.S. Central Command. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ↑ Barbash, Fred; Ryan, Missy; Gibbons-Neff, Thomas (25 October 2021). "Iran releases captured U.S. Navy crew members". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ↑ Browne, Tom LoBianco,Ryan (30 June 2016). "Navy report: Failure at every level for US ships captured by Iran | CNN Politics". CNN.com. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ AFP (30 June 2016). "Nine US navy personnel disciplined over Iranian capture of 10 sailors". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ↑ Trevithick, Tyler Rogoway and Joseph (14 April 2018). "Here Are All The Details The Pentagon Just Released Regarding Its Missile Attack On Syria (Updated)". The Drive. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ↑ "PATFORSWA Receives Two New Sentinel-Class U.S. Coast Guard Fast Response Cutters". DVIDS. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ↑ Burgess, Richard R. (10 December 2019). "Schultz: FRCs Expanding Coast Guard Reach in Pacific; Six Set for Persian Gulf". Seapower. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ↑ "Bahrain". Chuck Hill's CG Blog. 23 August 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ↑ "U.S. Ship Seizes Illegal Narcotics in Gulf of Oman". U.S. Central Command. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ↑ "U.S. Coast Guard in Middle East Seizes $85 Million in Heroin". U.S. Central Command. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ↑ "U.S. Coast Guard Ship Seizes $48 Million in Drugs in Middle East". U.S. Central Command. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ↑ "U.S. Naval Forces Intercept Explosive Material Bound for Yemen". U.S. Central Command. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ↑ "U.S. Seizes $80 Million Heroin Shipment in Gulf of Oman". U.S. Central Command. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ↑ Armed Forces Dispatch (13 July 2023). "Armed Forces Dispatch Sixty-Third Year No.8" (PDF). www.navydispatch.com. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ↑ "Coast Guard supports Operation Allies Welcome". United States Coast Guard. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ↑ "Task Force 59 Launches Aerial Drone from Coast Guard Ship in Middle East". U.S. Central Command. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ↑ "Task Force 59 Completes Digital Horizon Event". U.S. Central Command. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ↑ "U.S. Navy Sends First Unmanned Vessel Through Strait of Hormuz". The Maritime Executive. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ↑ "The Long Blue Line - 20 Years OIF: Coast Guard combat operations in Operation Iraqi Freedo". United States Coast Guard. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ↑ RFE/RL. "Iranian Ships, U.S. Coast Guard Vessels Meet In Tense Gulf Encounter". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ↑ Liebermann, Oren (27 April 2021). "Iranian attack boats harassed US warships in Persian Gulf again on Monday, Navy says | CNN Politics". CNN. Retrieved 23 December 2023.