白族 | |

|---|---|

Women dressed in Bai clothing | |

| Total population | |

| 1,858,063[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| China, mostly in the Yunnan Province (Dali area), Guizhou Province (Bijie area) and Hunan Province (Sangzhi area) | |

| Languages | |

| Bai, Chinese | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism, Benzhuism and Taoism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Han Chinese • Hui Other Sino-Tibetan peoples |

| Bai people | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 白族 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The Bai, or Pai (Bai: Baipho, /pɛ̰˦˨xo̰˦/ (白和); Chinese: 白族; pinyin: Báizú; Wade–Giles: Pai-tsu; endonym pronounced [pɛ̀tsī]), are an East Asian ethnic group native to the Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture of Yunnan Province, Bijie area of Guizhou Province, and Sangzhi area of Hunan Province. They constitute one of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognized by China. They numbered 1,933,510 as of 2010.[2]

Names

The Bai people hold the colour white in high esteem and call themselves "Baipzix" (pɛ˦˨ tsi˧, Baizi, 白子), "Bai'ho" (pɛ˦˨ xo˦, Baihuo, 白伙), "Bai yinl" (pɛ˦˨ ji˨˩, Baini, 白尼) or "Miep jiax". Bai literally means "white" in Chinese. In 1956, the Chinese authorities named them the Bai nationality according to their preference.

Historically, the Bai had also been called Minjia (民家) by the Chinese from the 14th century to 1949.[3]

The origin of the name Bai is not clear, but scholars believe that it has a strong connection to the first state Bai people built in roughly the 3rd century AD. This state, called Baizi Guo (白子國, State of Bai), was not documented in Chinese orthodox history but was frequently mentioned in the oral history of Yunnan Province. It was believed to be built by the first king, Longyouna (龍佑那), who was given the family name "Zhang" (張) by Zhuge Liang, the chancellor of the state of Shu Han (221–263 CE). Zhuge Liang conquered the Dali region at that time and picked up Longyouna and assisted him in building the State of Bai. The State of Bai was located in present-day Midu County, Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan Province.[4]

Modern identity

The Bai people are one of the most sinicized minorities in China. Although technically one of China's 55 official ethnic groups, it is difficult to qualify them as a distinct ethnic minority. As early as the 1940s, some rejected their non-Chinese origin and preferred to identify themselves solely as Chinese. The Bai ethnic label was not widely used or known until 1958. Today the Bai people accept minority status for pragmatic reasons but are culturally nearly indistinguishable from Han Chinese.[5][6]

One prerequisite for creating a hybrid form of Chinese would be a unique cultural identity, distinct from the Han, but the Bai people have been said by the sinologist Charles Patrick Fitzgerald to have held no ‘strong national feeling’ even before 1949. Hence, Fitzgerald, author of an authoritative study on Bai (whom he called by their former Chinese name, the Min-kia [minjia 民家]), said that many travellers regarded them as an ‘absorbed people hardly to be distinguished from Han Chinese.[7]

— Duncan Poupard

Location

Bai people live mostly in the provinces of Yunnan (Dali area), and in neighboring Guizhou (Bijie area) and Hunan (Sangzhi area) provinces. Of the 2 million Bai people, eighty percent live in concentrated communities in the Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan Province.[8]

History

The origin of Bai was heavily debated over roughly the past century. Ironically those debates were of the groups of people who were assimilated into Bai, rather than the issue per se. According to archaeological excavations around the Lake Erhai, Bai people could have originated in the lake area. The earliest human site was discovered in the early 20th century, which was called the paleolithic Malong relics of Mt. Cangshan (苍山马龙遗址), dated circa 4000 bp. The late sites include Haimenkou of Jianchuan (剑川海门口, 3000 bp), Baiyangcun of Binchuan (宾川白羊村, 3500 bp), and Dabona of Xiangyun(祥云大波那, 2350 bp).

The Bai are mentioned in Tang dynasty texts as the 'Bo (or Bai) People'. If the Bo transcription is correct then it would mean the earliest mention of the Bai was in the third century BCE in a text called Lüshi Chunqiu (Spring and Autumn Annals of Master Lü Buwei). It was then mentioned again in Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian in the first century BCE.[9]

The Bai made up one of the tribes who helped establish the Nanzhao Kingdom (649-902). The Dali Kingdom (937-1253) was founded by a Bai named Duan Siping whose family had played major roles in the Nanzhao Kingdom. It's likely that the Bai were one of the elite ethnic groups that ruled and composed the population of the two kingdoms. After the collapse of the Dali Kingdom by the Mongols, the Bai never again enjoyed full political independence.

Language

An estimated 1,240,000 (as of 2003) of the Bai speak the Bai language in all its varieties. As of 2004, only Bai people who lived in mountains spoke Bai as their only language, but some Han Chinese in Dali also spoke Bai due to local influence. Among modern Bai people, Chinese is usually used for popular media such as radio, television, and news, while Bai is relegated to folk-arts related activities.[10] No book in the Bai language has been published as of 2005.[9]

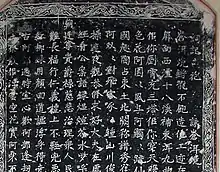

The origins of the language have been obscured by intensive Chinese influence over an extended period. Several theories have been proposed, including categorizing it as a sister language of Chinese, a separate group within the Sino-Tibetan family, or in a category more related to the Thai language or Hmong language.[11] Superficially, the Bai lexicon and grammar is closer to Chinese languages but it is also shares common vocabulary items with the Lolo-Burmese languages.[9] According to the Manshu (Book of Barbarians) by Fan Chuo (9th century), the Baiman's pronunciation of Chinese was the most accurate out of all the tribes in the area.[12] Scriptures from Nanzhao unearthed in 1950s show that they were written in the Bai language (similar to Chữ Nôm and the Old Zhuang script) but it does not seem Nanzhao ever attempted to standardize or popularize the script. The same was true for its successor, the Dali Kingdom. During the Ming dynasty, the government began offering state examinations in Yunnan, which solidified Classical Chinese as the official language.[13]

Religion

Although most Bai people adhere to Azhaliism, a form of Buddhism that traces its history back to the Nanzhao Kingdom,[9][14][15] they also have a native religion of Benzhuism: the worship of ngel zex (本主; běnzhǔ), local gods and ancestors. Ngel zex could be any heroes in history, the prince of the Nanzhao regime, a hero of folklore or even a tiger (for instance, Laojun Jingdi 老君景帝 is a tiger).

Most Bai people don't belong to any religion. There are minorities practicing Taoism and Christianity. George Clarke, arrived in 1881, was the first Protestant missionary to Bai population. The recent estimation of Bai Christian population is 50,000.[16]

There are a few villages in Yunnan where residents are Muslims, but speak Bai as their first language. These people are officially classified by Chinese authorities as belonging to the Hui nationality and call themselves Bai Hui ("Bai-speaking Muslims"). They usually say that their ancestors were Hui people, who came to Yunnan as followers of the Mongolian army in the 14th century.[17]

Culture

Gender

Gender roles were relatively equal in Bai society and women were not considered inferior to men. Having only daughters and no sons was not considered a tragedy.[18]

Agriculture

Most Bai were subsistence rice farmers, but also cultivated wheat, vegetables, and fruits. Unlike the Han and most other Chinese minority groups, the Bai ate cheese and made it from either cow or goat milk. The leftover whey from the process of cheese-making was fed to pigs. Those who lived around Erhai Lake fished.[19]

Clothing

The Bai people, as their name would suggest, favor white clothes and decorations. Women generally wear white dresses, sleeveless jackets of red, blue or black color, embroidered belts, loose trousers, embroidered shoes of white cloth, and jewelry made of gold or silver. Women in Dali traditionally wear a white coat trimmed with a black or purple collar, loose blue trousers; embroidered shoes, silver bracelets and earrings. Unmarried women wear a single pigtail on the top of the head, while married women roll their hair. The men wear white jackets, black-collared coats, and dark loose shorts. Their headwear and costume reflect the Bai symbols: the snow, the moon, the flower, and the wind.

The modern Bai are famous for their tie dyes and use them for wall hangings, table decorations, clothing, etc.

Many Bai women style their hair in a long braid wrapped in a headcloth. This style is called "the phoenix bows its head".[20]

Arts

The Bai have a traditional form of theater called Chuichuiqiang. However, this local tradition is endangered just as traditional Bai culture is in general.[9]

Festivals

Raosanlin

The three major Bai festivals are called the Raosanlin (Walking Around Three Souls). The most important one is the Third Month Fair, held annually at the foot of Mount Cang in Dali between the fifteenth and the twentieth day of the third lunar month. Originally it was a religious activity to rally and pay homage, but it gradually evolved into a fair including performances of traditional sports and dance, as well as the trade of merchandise from different regions. The second festival is the Shibaoshan Song Festival, and the third is the Torch Festival, held on the 25th day of the sixth lunar month to wish health and a good harvest. On that evening, the countryside is decorated with banners with auspicious words written upon them. Villagers then light torches in front of their gates and walk around the fields while holding yet more torches in order to catch pests.[18]

Tea ceremony

The Bai tea ceremony, San Dao Cha 三道茶 (Three Course Tea), is most popular among the Bai in the Dali area and is a common sight at festivals and marriages. It is both a cultural ceremony and method of honouring a guest.[21] The ceremony is often described in Mandarin as, 'Yiku, ertian, sanhuiwei' 一苦二甜三回味 (First is bitter, Second is sweet, Third brings reflection (aftertaste)).[22]

The first tea course starts with baking the tea leaves in a clay pot over a small flame, shaking the leaves often whilst they bake. When they turn slightly brown and give off a distinct fragrance, heated water is added to the pot. The water should immediately begin bubbling. When the bubbling ceases a small amount of bitterly fragrant, concentrated tea remains. Due to the sound the hot water makes when it enters the clay pot the first course tea was, in previous times, also known as Lei Xiang Cha 雷响茶 (Sound of Thunder Tea).[21]

The second course is sweet tea. Pieces of walnut kernel and roasted rushan (乳扇, lit. milk fan), a dried cheese specific to the Dali region,[23] are put into a tea cup with brown sugar and other ingredients. Boiling water is added and the tea is then offered to the guest. This tea is sweet without being oily, so the guest can easily drink it.[24]

The third tea is made by mixing honey, Sichuan pepper, slices of ginger and cassia together in a china cup with hot Cangshan Xue green tea.[24] The product is a tea that is sweet, coarse and spicy all at once. This Dali specialty has a noticeable aftertaste, which meant it was known as Hui Wei Cha 回味茶 (Reflection Tea).[21]

The 18 procedures of the tea ceremony are governed by strict etiquette, which follows the principles of etiquette, honesty and beauty. As such, the tea ceremony is considered by some to perfectly embody the hospitable Bai people's current customs.[22]

Livelihood

Primary occupations

Most Bai are agriculturalists. They cultivate many crops like rice, wheat, rapeseed, sugar, millet, cotton, cane, corn, and tobacco. However, some Bai also engage in fishing and selling local handicrafts to tourists.[20]

Cormorant fishing

Bai fishermen have trained cormorants to fish since the 9th century. Decreases in water quality and the high costs of cormorant training have resulted in recent disuse of the practice, though cormorant fishing is still done by local fishers today for tourists.[25]

Architecture

The Bai architecture is characterized by three buildings forming a U and a fourth wall as a screen. The middle has a courtyard. The houses are usually built out of brick and wood, and the main room is in the middle (opposite the screen wall). The screen wall is built with brick and stone. The house is painted in white with black tile paintings depicting animals and other natural images. The detailing usually is made of clay sculpture, woodcarving, colored drawing, stone inscription, marble screens and dark brink. It produces a very striking and elegant effect.

Dali is well known for its marble. The name for marble is 'Dali marble' in Chinese. It is used in modern architecture by the Bai.

Notable Bai

- Duan Siping (段思平) - founder of the Kingdom of Dali

- Shen Yiqin (谌贻琴) - Communist Party Secretary of Guizhou

- Wang Xiji (王希季) - aerospace engineer, designer of the Long March 1 rocket

- Xu Lin (徐琳) - linguist, one of two founders of modern grammar of Bai language.

- Yang Chaoyue (杨超越) - singer, former member of Rocket Girls 101

- Yang Liping (杨丽萍) - dancer

- Yang Rong (楊蓉) - actress

- Yang Yuntao (楊雲濤) - dancer

- Zhang Le Jin Qiu (张乐进求) - legendary ancestor of the Bai

- Zhang Lizhu (张丽珠) - gynecologist

- Zhang Jiebao (张结宝) - a famous bandit leader, active in the 1920s in northwestern Yunnan.

- Zhao Fan (趙藩) - scholar, calligrapher and poet

- Zhao Shiming (赵式铭) - scholar, the first one who studied the Bai language the most systematically.

- Zhao Yansun (赵衍荪) - linguist, one of two founders of modern grammar of Bai language.

- Zhou Baozhong (周保中) - military general, who led the battles against the Japanese invasion in Northeastern China.

- Fiona Ma (馬世雲) - American Politician.

- Dianxi Xiaoge (滇西小哥) - Youtuber

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ "The Bai Ethnic Group". China.org.cn. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "Tabulation on the 2010 Population Census of the People's Republic of China".

- ↑ "Voice quality" (PDF). Sealang.net. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ↑ 释, 同揆 (c. 1681). 洱海丛谈(Erhai Congtan). p. 3.

- ↑ Wu, David Y. H. (1990). "Chinese Minority Policy and the Meaning of Minority Culture: The Example of Bai in Yunnan, China". Human Organization. 49 (1): 1–13. doi:10.17730/humo.49.1.h1m8642ln1843n45. JSTOR 44125990.

- ↑ "Bai, Southern in China".

- ↑ Poupard, Duncan James (2019). "Translation as hybridity in Sinophone Bai writing". Asian Ethnicity. 20 (2): 210–227. doi:10.1080/14631369.2018.1524286. S2CID 149581116.

- ↑ "Ethnic Groups". China.org.cn. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Skutsch, Carl, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. New York: Routledge. pp. 175–176. ISBN 1-57958-468-3.

- ↑ Wang 2004, p. 278.

- ↑ Wang, Feng (2005). "On the genetic position of the Bai language". Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale. 34 (1): 101–127. doi:10.3406/clao.2005.1728.

- ↑ Wang 2004, pp. 279.

- ↑ Wang 2004, pp. 280.

- ↑ "Ethnic Groups - china.org.cn". China.org.cn. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ↑ "Ethnic Groups - china.org.cn". China.org.cn. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ↑ Hattaway, Paul (2004). Peoples of the Buddhist world : a Christian prayer diary. GMI (Global Mapping International). p. 7. ISBN 1903689422. OCLC 83780996.

- ↑ Gladney, Dru C. (1996). Muslim Chinese: Ethnic Nationalism in the People's Republic (2 ed.). Harvard Univ Asia Center. p. 33. ISBN 0-674-59497-5. (1st edition appeared in 1991)

- 1 2 West 2009, p. 80.

- ↑ West 2009, p. 79.

- 1 2 Winston, Robert, ed. (2004). Human: The Definitive Visual Guide. Dorling Kindersley. p. 449. ISBN 0-7566-0520-2.

- 1 2 3 "大理白族"三道茶"(民俗风情)". People.com.cn. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- 1 2 "大连日报". Daliandaily.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "100道 云南美食 图文版 大理乳扇 大理名菜 大理小吃-大理-昆明中国国际旅行社有限公司". 7c6u.cn. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- 1 2 "腾讯. 文学 - 文字之美,感动心灵". Book.qq.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Larson-Wang, Jessica. "The History Behind the Cormorant Fishermen of Erhai Lake". Culture Trip. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

Sources

- Travel China Guide - Bai minority ethnic group

- Wang, Feng (2004). "Language policy for Bai". In Zhou, Minglang (ed.). Language policy in the People's Republic of China: Theory and practice since 1949. Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 278–287. ISBN 978-1-4020-8038-8.

- West, Barbara A. (2009), Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania