| Pampas deer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male Pampas deer in Serra da Canastra National Park. | |

| |

| Female Pampas deer nursing fawn in the Pantanal, Brazil. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Cervidae |

| Subfamily: | Capreolinae |

| Genus: | Ozotoceros Ameghino, 1891 |

| Species: | O. bezoarticus |

| Binomial name | |

| Ozotoceros bezoarticus | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Cervus bezoarticus Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The Pampas deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus) is a species of deer that live in the grasslands of South America at low elevations.[3] They are known as veado-campeiro in Portuguese and as venado or gama in Spanish. It is the only species in the genus Ozotoceros.

Their habitat includes water and hills, often with winter drought, and grass that is high enough to cover a standing deer.[4] Many of them live on the Pantanal wetlands, where there are ongoing conservation efforts, and other areas of annual flooding cycles. Human activity has changed much of the original landscape.[5]

They are known to live up to 12 years in the wild, longer if captive, but are threatened due to over-hunting and habitat loss.[6] Many people are concerned over this loss, because a healthy deer population means a healthy grassland, and a healthy grassland is home to many species, some also threatened. Many North American birds migrate south to these areas, and if the Pampas deer habitat is lost, they are afraid these bird species will also decline.[7] There are approximately 80,000 Pampas deer total, with the majority of them living in Brazil.[8]

Taxonomy and evolution

Fossil records indicate that New World deer traveled to South America from North America as part of the Great American Interchange around 2.5 million years ago, following the formation of the Isthmus of Panama. They rapidly evolved into different species, with only a few surviving today. Due to the large continental glaciers and the high soil acidity in areas where there were no glaciers, a huge part of the fossil record has been destroyed, so there is no indication of what these early New World deer looked like. Fossil records begin with clear differentiation and are close to what they look like now. The Pampas deer evolved as plains dwellers; their direct ancestor first appeared during the Pleistocene epoch.[9][10]

The deer may have evolved without culling predators because when alarmed, they stamp their feet, have a particular trot and whistle, and deposit odor.[3] Pampas deer have a similar gene pattern to the related marsh deer of the genus Blastocerus, having two fused chromosomes.[3]

There are five recognised subspecies:[11]

- O. b. bezoarticus - eastern and central Brazil, south of the Amazon river into Uruguay

- O. b. arerunguaensis - northwestern Uruguay

- O. b. celer - southern Argentina

- O. b. leucogaster - southwestern Brazil, southeastern Bolivia, Paraguay, and northern Argentina

- O. b. uruguayensis - eastern Uruguay

Pampas deer are among the most genetically polymorphic mammals. Their current high nucleotide diversity shows that they had very large numbers in the recent past.[9]

Physical characteristics

Pampas deer have tan fur, lighter on their undersides and insides of legs. Their coats do not change with the seasons. They have white spots above their lips and white patches on their throats.[3] Their shoulder height is 60–65 cm (24–26 in) in females and 65–70 cm (26–28 in) in males.[12] Their tails are short and bushy, 10 cm to 15 cm long, and when they run, they lift their tail to reveal a white patch, just like white-tailed deer.[3]

Adult males typically weigh 24–34 kg (53–75 lb), but have been documented up to 40 kg (88 lb), and females typically weigh 22–29 kg (49–64 lb).[12] They are a small species of deer, with relatively little sexual dimorphism. Males have small, lightweight antlers that are 3-pronged, which go through a yearly cycle of shedding in August or September, with a new grown set by December. The lower front main prong of the antlers is not divided, but the upper prong is. Females have hair whorls that look like tiny antlers stubs. Females and males have different stances during urination.[3][13] Males have a strong smell secreted from glands in their back hooves that can be detected up to 1.5 km away.[4] Compared to other small ruminants, the males have small testicles relative to their body size.[14]

Biology and behavior

In Argentina, the mating season is December to February. In Uruguay, the mating season is February to April. Courtship behavior is submissive, such as low stretching, crouching, and turning away.[15] The male initiates courtship with a low stretch. He makes a soft buzzing sound. He nuzzles the female and may flick his tongue at her, and averts his eyes. He stays near her, and may follow her for a long time, smelling her urine. Sometimes the female responds to courtship by lying on the ground.[3]

Pampas deer do not defend territory or mates, but do have displays of dominance. They show dominance by keeping their heads up and trying to keep their side forward, and use slow, deliberate movements. When bucks are challenging each other, they rub their horns into vegetation and scrape them on the ground. They may urinate into the scrape they've made, and sometimes defecate. They rub the scent glands on their heads and faces into plants and objects. They usually do not fight, but just spar with each other, and they do commonly bite. Sparring is initiated by the smaller buck touching noses with the larger buck.[3] Groups are not separated by sex, and bucks will drift between groups. There are usually only 2-6 deer in a group, but there can be many more in good feeding areas. They do not have monogamous pairs, nor are there harems.[3][4]

When they feel they may be in danger, they hide low in the foliage and hold, and then bound off about 100–200 meters, often looking back at the disturbance. Because they bound in long flat jumps and have not been observed to run, they are not thought to be endurance runners. If they are alone, they may just quietly slip away. Females with a fawn will fake a limp to distract a predator, or if they are unsure of a situation, such as if a human appears.[3]

They will often stand on their hind legs to reach food or see over something. They are sedentary, with no seasonal or even daily movements. They usually feed regularly during the day, but sometimes have nocturnal activity.[4] The Pampas deer are very curious and like to explore. Although this is endearing to observers, their lack of fleeing at the sight of humans makes them easier for poachers to kill.[3]

Diet

Pampas deer have been seen eating new green growth, shrubs, and herbs. Most of the plant life they consume grows in moist soils. To see if Pampas deer compete with cattle for food, their feces were studied and compared to cattle feces. They do in fact eat the same plants, but in different proportions. The pampas deer eat less grass and more forbs (flowering broad leafed plants with soft stems) and browse (shoots, leaves, and twigs), respectively. During the rainy season, 20% of their diet consists of new grasses. They will move with the availability of food, particularly the flowering plants. The presence of cattle increases the amount of sprouting grass, which is preferred by Pampas deer, furthering the idea that the deer do not compete with cattle for food.[16] Opposing research shows that Pampas deer avoid areas inhabited by cattle, and when cattle are absent have much larger home ranges.[7]

Reproduction/calves

Fawns can be seen at any time of year, but there is a peak in September and November. Females separate themselves from the group to give birth, and keep the fawn hidden away. After giving birth, the female goes into heat and usually mates within the next 48 hours. The fawns are small and spotted, and lose their spots at about 2 months old. Usually only one fawn weighing about 2.2 kg is born after a gestation period lasting over 7 months. At 6 weeks, they can eat solid food and begin to follow their mother. They stay with their mothers for at least a year, and also reach sexual maturity at about a year.[4]

Threat of extinction

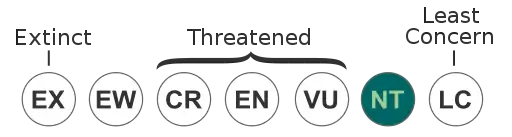

The Pampas deer of southern Argentina, once very abundant, are now considered a threatened species by the IUCN. The IUCN separates the subspecies O. b. celer in southern Argentina as endangered. The diseases that particularly plague O. b. celer are gut parasites and foot and mouth diseases. Their overall decline is also due (in part) from hunting and poaching, but also from agricultural habitat loss (thus exposing deer to diseases from domesticated and feral livestock), competition from more recently-introduced wildlife, and general over-exploitation. There is less than 1% of their natural habitat left that was present in 1900.[9] The deer in Argentina and Uruguay have fewer natural predators. They used to be the prey of cougars and many more jaguars. Those in Brazil still have the felines to fear. Some areas with low population are easily attributed to poaching, due to a sudden lower number of deer in an area. In the mid-1970s, ten individuals, out of a group of 16 located in Punta Medanos, were killed by poachers. The rest were extirpated by extensive human activity. Lack of funding and technology have made it difficult for biologists to track and aid the deer population, while donations and grants from organizations and universities in the United States have helped immensely with the situation. In 1975, there were less than 100 of the subspecies O. b. celer, but by 1980, there were around 400. The population has been continuing to increase, although not at an incredibly fast pace. One of the discrepancies is simply the fact that, later on, previously unknown subspecies and groups were discovered.[8]

Local people often blame the deer for outbreaks of disease in their livestock, particularly Brucellosis in cattle. In one instance, the Uruguayan government was going to cull some of their Pampas deer population, until research by field veterinarians had shown that Pampas deer rarely carry the disease. Only then did the government give them time to assess the deer’s health. Funded by the Disney Conservation Fund, they were able to prove that the deer pose no threat of spreading disease to livestock.[7]

Trade for commercial purposes is banned. They are legally protected in Argentina, where there is a private and federal reserve set aside for the deer. In some areas, strict regulations on poaching is all that was necessary to quickly increase the population size. Increasing public knowledge, and monitoring road construction operations, has also helped. They reproduce well in captivity, and are sometimes reintroduced into the wild.[9]

In 2006, GPS trackers were placed on 19 Pampas deer, although 8 of those did not record data. The individuals were monitored over a period of 4–18 days, for researchers to collect data on their movements, and thus understand how to better help them.[17]

Relations with humans and culture

The Pampas deer have been harvested into the millions. Between 1860 and 1870, documents for the port of Buenos Aires alone show that two million Pampas deer pelts were sent to Europe. Many years later, as roads were built through the pampas, cars made it even easier for poachers to get to the deer. They were also killed for food, medicinal purposes, and for sport. As of 2003, there are fewer than 2,000 of them in Argentina and Uruguay. Both Argentina and Uruguay have declared the Pampas deer "natural monuments" but the hunting continues, although much less frequently now. The decimation of the Pampas deer has been likened to that of the bison of North America. Also similar to the bison, is the role they played in the life of the Native Americans of Uruguay and Argentina, being used for food, hides, and medicine. The Native Americans at first participated in the harvesting of the Pampas deer pelts for sale, and in spite of that, the deer population stayed strong until the Native Americans of those countries were defeated by European settlers. The settlers brought large agricultural expansion, uncontrolled hunting, and new diseases to the deer with the introduction of new domestic and feral animals.[4]

Some landowners have set aside some of their property as a reserve for the deer, as well as keeping cattle instead of sheep. Sheep graze much more on the land and are more of a threat to the deer. The owners that choose cattle are doing it as a service, because more money is made from raising sheep than cattle. Conservationists encourage this trend by sharing research that more edible vegetation is available on ranches with cattle and deer during times of drought than on ranches with cattle and sheep.[7]

References

- ↑ González, S.; Jackson, III, J.J.; Merino, M.L. (2016). "Ozotoceros bezoarticus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T15803A22160030. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T15803A22160030.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Geist, Valerius. Deer of the world their evolution, behaviour, and ecology. Mechanicsburg, Pa: Stackpole Books, 1998

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 P., Walker, Ernest. Walker's Mammals of the world. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1991

- ↑ Harris, Monica B.; Tomas, Walfrido; Mourao, Guilherme; Da Silva, Carolina J.; Guimaraes, Erika; Sonoda, Fatima; Fachim, Eliani (2005). "Safeguarding the Pantanal Wetlands: Threats and Conservation Initiatives". Conservation Biology. 19 (3): 714–20. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00708.x. S2CID 85322187.

- ↑ Moore, Don (2003). "A Delicate Deer". Wildlife Conservation. 106: 6–7.

- 1 2 3 4 Villa, A. R.; Beade, M. S.; Lamuniere, D. Barrios (2008). "Home range and habitat selection of pampas deer". Journal of Zoology. 276: 95–102. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2008.00468.x.

- 1 2 IUCN Mammal Red Data Book. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN, 1982

- 1 2 3 4 Gonzales, S.; Maldonado, J. E.; Leonard, J. A.; Vila, C.; Duarte, J. M. Barbanti; Merino, M.; Brum-Zorilla, N.; Wayne, R. K. (1998). "Conservation genetics of the endangered Pampas deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus)". Molecular Ecology. 7 (1): 47–56. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00303.x. PMID 9465416. S2CID 21330270.

- ↑ Grzimeks Animal Life Encyclopedia Mammals (Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia). Vol. 15. Detroit: Gale Cengage, 2003

- ↑ Ungerfield, Rodolfo; González-Pensado, Solana; et al. (June 2008). "Reproductive biology of the pampas deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus): a review". Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica. 50 (1): 16. doi:10.1186/1751-0147-50-16. PMC 2430702. PMID 18534014.

- 1 2 Mattioli, S. (2011). Pampas Deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus), p. 437 in: Wilson, D.E., & Mittermeier, R.A., eds. (2011). Handbook of the Mammals of the World, Hoofed Mammals, Vol. 2. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. ISBN 978-84-96553-77-4

- ↑ Jackson, J. "Behavioural observations on the argentinian pampas deer." Ozotoceros bezoarticus celer (1943): 107-116.

- ↑ Pérez, William, Noelia Vazquez, and Rodolfo Ungerfeld. "Gross anatomy of the male genital organs of the pampas deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus, Linnaeus 1758)." Anatomical science international 88.3 (2013): 123-129.

- ↑ Morales-Piñeyrúa, Jéssica T., and Rodolfo Ungerfeld. "Pampas deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus) courtship and mating behavior." Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 54.1 (2012): 1.

- ↑ People In Nature Wildlife Conservation in South and Central America. New York: Columbia UP, 2005

- ↑ Zucco, Carlos; Mourao, Guilherme (2009). "Low-Cost Global Positioning System Harness for Pampas Deer". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 73 (3): 452–57. doi:10.2193/2007-492. S2CID 86182493.

Further reading

- Ungerfeld, R; González-Pensado, S; Bielli, A; Villagrán, M; Olazabal, D; Pérez, W (2008). "Reproductive biology of the pampas deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus): a review". Acta Vet Scand. 50 (1): 16. doi:10.1186/1751-0147-50-16. PMC 2430702. PMID 18534014.

- Pérez, W; Clauss, M; Ungerfeld, R (Aug 2008). "Observations on the macroscopic anatomy of the intestinal tract and its mesenteric folds in the pampas deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus, Linnaeus 1758)". Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia. 37 (4): 317–21. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0264.2008.00855.x. PMID 18400045. S2CID 20426966. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05.