Panzós | |

|---|---|

Municipality of Guatemala | |

Port of Panzos in the 1900s | |

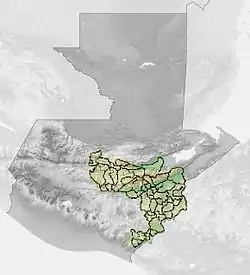

Panzós Location in Alta Verapaz  Panzós Panzós (Guatemala) | |

| Coordinates: 15°24′N 89°40′W / 15.400°N 89.667°W | |

| Country | |

| Department | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jaime León (LIDER) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 354 sq mi (917 km2) |

| Population (2018 census)[1] | |

| • Total | 71,846 |

| • Density | 200/sq mi (78/km2) |

| Climate | Am |

Panzós (Spanish pronunciation: [panˈsos]) is a town with a population of 22,068 (2018 census)[2] and a municipality in the Guatemalan department of Alta Verapaz.

On 29 May 1978, the village of Panzós was the site of a massacre in which between 30 and 106 local inhabitants (figures vary) were killed by the army.[3][4][5]

The name Panzós means "place of the green waters" in reference to the nearby Polochic River and swamps full of alligators and birds.[6]

History

In late 19th century Alta Verapaz, German settlers owned almost 75% of the region's total land. It got to a point that the Germans were taking over land and people and a governor reported that there were peasants who vanished, fleeing from the landowners.

Julio Castellanos Cambranes[7]

The Polochic river valley was originally inhabited by Q'eqchi' and Poqomchi' peoples. The first Spanish settlement, according to Domingo Juárez, was founded there on 11 October 1825; however, other historians[8] specify 11 October 1861 as its foundation date. Later on, government decree #38 of 1871, in which all Guatemalan municipalities were asked to elect representatives to the National Assembly, shows Panzós a town in District 35. In 1891, Panzós became part of Alta Verapaz Department.

After the Liberal revolution of 1871, president Justo Rufino Barrios (1873-1885) started granting land to German settlers in the area.[9] By Decree #170 (or Census Decree), the government allowed confiscation of Indigenous land that had remained protected up to that point to make it easier for the Germans and liberal military officers to get land of their own.[10] Since then, the main commercial and agricultural activity in the region has been coffee, cardamom, and bananas.[11] The main characteristics of the productive system of those years was the accumulation of land by a few owners[12] and a sort of "hacienda servitude" based on the legal exploitation of the natives.[7]

In the 1880s, Panzós had become a very important commercial river port heavily used for coffee exports.[13] The finished product was carried by oxen carts over poorly kept roads or on small boats through creeks to the port, and from there it was loaded into larger ships and sent to the Caribbean Sea and then on to Europe or other destinations.[13] This archaic system changed drastically in the 1890s, once the Verapaz Railroad was built.

Verapaz Railroad

The construction of the Verapaz Railroad began on 15 January 1894 with a contract for 99 years between Guatemala, then ruled by president José María Reina Barrios, and Walter Dauch, representative of the Verapaz Railroad & Northern Agency Ltd. The contract settled the rules for the construction, maintenance, and exploitation of a 30-mile railroad line between Panzós and Pancajché. Passenger service travelled twice a week on Mondays and Thursdays, mail arrived by ship every Wednesday and cargo came from Livingston, Izabal. Besides, there were train stops in Santa Rosita, Santa Catalina La Tinta, and Papalhá.[14]

In 1898, it was reported that given the coffee prosperity in Cobán, which was the third largest city in Guatemala, the railroad was to be extended to that city.[14] The railroad was in operation until 1965, when it was superseded by truck and highways.

Verapaz Railroad maiden voyage in 1894.

Verapaz Railroad maiden voyage in 1894. Verapaz Railroad steamboat sailing the Polochic river.[15]

Verapaz Railroad steamboat sailing the Polochic river.[15] Coffee transport.[15]

Coffee transport.[15] Verapaz Railroad engine in the 1900s.

Verapaz Railroad engine in the 1900s.

Franja Transversal del Norte and Panzós massacre

The Northern Transversal Strip was officially created during the government of General Carlos Arana Osorio in 1970 by Legislative Decree 60-70 for agricultural development.[16] The decree stated: "It is of public interest and national emergency, the establishment of Agrarian Development Zones in the area included within the municipalities: Santa Ana Huista, San Antonio Huista, Nentón, Jacaltenango, San Mateo Ixtatán, and Santa Cruz Barillas in Huehuetenango; Chajul and San Miguel Uspantán in Quiché; Cobán, Chisec, San Pedro Carchá, Lanquín, Senahú, Cahabón and Chahal, in Alta Verapaz and the entire department of Izabal."[17]

On 27 May 1978, when natives from San Vicente (in Panzós) went to work the land on the shores of the Polochic river, the sons of a local landlord showed up with several armed soldiers and intimidated the natives to stop demanding land for themselves.[18] The same day, the military detained two peasants in La Soledad and roughed up several more.[18][lower-alpha 1] There was a small disturbance and one of the peasants was killed.[18]

On 28 May, peasants from La Soledad and Cahaboncito presented a document previously prepared by FASGUA to mayor Walter Overdick Garcia in order for him to read it out loud.[19] In that document, FASGUA asked the mayor to mediate "for the peasants' sake and try to solve the problems they had".[20]

On 29 May 1978, to pressure the authorities for their land demands and to protest against the abuses of landlords and military and civil authorities, peasants from the settlements of Cahaboncito, Semococh, Rubetzul, Canguachá, Sepacay, Moyagua, and La Soledad decided to protest in downtown Panzós. Hundreds of native men, women, and children went to the central square, bringing along their machetes and other agricultural instruments. One of those who participated in the demonstration later recalled: "the idea was not to fight anybody, we only wanted to clarify the land situation. People came from various locations and they did not have firearms with them". [21] That same day, after an unclear provation, the army massacred the peasants who had gathered peacefully.[22] An unclear number of people died under the fire of machine guns.[23]

Climate

Panzós has a tropical monsoon climate (Köppen: Am).

| Climate data for Panzós | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.4 (86.7) |

32.0 (89.6) |

33.6 (92.5) |

34.8 (94.6) |

34.6 (94.3) |

34.1 (93.4) |

33.2 (91.8) |

33.2 (91.8) |

33.2 (91.8) |

32.4 (90.3) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.3 (86.5) |

32.7 (90.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.0 (78.8) |

26.7 (80.1) |

28.1 (82.6) |

29.1 (84.4) |

29.4 (84.9) |

29.2 (84.6) |

28.8 (83.8) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.0 (82.4) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.9 (82.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 21.7 (71.1) |

21.4 (70.5) |

22.6 (72.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.6 (74.5) |

22.6 (72.7) |

21.8 (71.2) |

23.2 (73.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 85 (3.3) |

54 (2.1) |

66 (2.6) |

70 (2.8) |

216 (8.5) |

503 (19.8) |

525 (20.7) |

381 (15.0) |

380 (15.0) |

244 (9.6) |

124 (4.9) |

101 (4.0) |

2,749 (108.3) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org[24] | |||||||||||||

Geographic location

See also

Notes and references

Notes

References

- ↑ Citypopulation.de Population of departments and municipalities in Guatemala

- ↑ Citypopulation.de Population of cities & towns in Guatemala

- ↑ Brockett, Charles. "Political Movements and Violence in Central America". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- ↑ Peters, Moira (2008-05-04). "Portraits of Strength : The women of Panzós". The Dominion. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- ↑ Kobrak n.d.

- ↑ Iain Stewart; Mark Whatmore; Peter Eltringham (2002). The Rough Guide to Guatemala. Rough Guides. p. 315. ISBN 978-1-85828-848-2.

- 1 2 Castellanos Cambranes 1992, p. 327.

- ↑ Morales Urrutia 1961.

- ↑ Castellanos Cambranes 1992, p. 305.

- ↑ Castellanos Cambranes 1992, p. 316.

- ↑ Testimony, in the Center of Social History Research. Panzós: CEIHS, 1979.

- ↑ Mendizábal P. 1978, p. 76.

- 1 2 Maudslay & Maudslay 1899, pp. 90, 105, 241.

- 1 2 La Ilustración del Pacífico & 15 March 1898, p. 206

- 1 2 La Ilustración del Pacífico & 15 March 1898, pp. 203–204

- ↑ "Franja Transversal del Norte". Wikiguate. Guatemala. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ↑ Solano 2012, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico: Agudización 1999, p. Reference witness

- ↑ Impacto & 19 July 1978, p. 7.

- ↑ Comisión de Solidaridad con Panzós memorandum, 12 July 1978.

- ↑ Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico: Agudización 1999, p. Direct witness (peasant leader).

- ↑ La masacre de Panzós, artículo de M. Escalante Herrera en el sitio web PBase.

- ↑ Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico: No.9 1999

- ↑ "Climate: Panzós". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- 1 2 SEGEPLAN n.d.

Bibliography

- Albizures, Arturo; Hernández, Boris (2013). "Morir para ganar la vida". Noticias Comunicarte, Asociación guatemalteca para la comunicación del arte y cultura (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- Álvarez S., Benigno; Monzón, Flavio; Monzón, Héctor; Ayala, Raúl Aníbal; González, Joaquín; Cazs, Mario; Borges, José María (1978). "Acta de audiencia de fecha 5 May 1978" (in Spanish). Cobán, Alta Verapaz: Gobernación Departamental de Alta Verapaz.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Castellanos Cambranes, Julio (1992). "Tendencias del desarrollo agrario, en 500 años de lucha por la tierra" (in Spanish). 1. Guatemala: FLACSO.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico: Agudización (1999). "Agudización de la Violencia y Militarización del Estado (1979-1985)". Guatemala: Memoria del Silencio (in Spanish). Programa de Ciencia y Derechos Humanos, Asociación Americana del Avance de la Ciencia. Archived from the original (Online edition) on 6 May 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- — (1999). "Caso ilustrativo n.º 9: La masacre de Panzós". Guatemala: Memoria del Silencio. Programa de Ciencia y Derechos Humanos, Asociación Americana del Avance de la Ciencia. Archived from the original (Online edition) on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Diario de Centro América (1978). "Entrevista a Walter Overdick, alcalde de Panzós". Diario de Centro América, Periódico Oficial de la República de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala.

- Diario La Tarde (31 May 1978). "Situación en Panzós". Diario La Tarde (in Spanish). Guatemala. p. 4.

- Díaz Molina, Carlos Leonidas (1998). "Que fluya la verdad". Revista Crónica (in Spanish). Guatemala.

- García Arriaga, Marlon (2011). Panzós, 33 años después (1978-2011) (PDF) (in Spanish). Guatemala: FLACSO y Rights action.

- Impacto (19 July 1978). "Aumenta la tensión en Panzós". Impacto (in Spanish). Guatemala. p. 7.

- Kobrak, Paul (n.d.). "Organizing and Repression: 1978: The popular movement". Organizing and Repression in the University of San Carlos, Guatemala, 1944 to 1996. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- La Ilustración del Pacífico (15 March 1898). "La revolución de septiembre". La Ilustración del Pacífico (in Spanish). Guatemala: Siguere, Guirola y Cía. II (38).

- Maudslay, Alfred Percival; Maudslay, Anne Cary (1899). "A glimpse at Guatemala, and some notes on the ancient mmonuments of Central America" (PDF) (in Spanish). Londres: John Murray.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Mendizábal P., Ana Beatriz (1978). "Estado y Políticas de Desarrollo Agrario. La Masacre Campesina de Panzós" (PDF). Escuela de Ciencia Política (in Spanish). Guatemala: Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala.

- Morales Urrutia, Mateo (1961). Política administrativa, la división de la República (in Spanish). Vol. 2. Guatemala: Iberia-Gutenberg.

- SEGEPLAN (n.d.). "Municipios de Alta Verapaz, Guatemala". Secretaría General de Planificación y Programación de la Presidencia de la República (in Spanish). Guatemala. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Solano, Luis (2012). Contextualización histórica de la Franja Transversal del Norte (FTN) (PDF) (in Spanish). Centro de Estudios y Documentación de la Frontera Occidental de Guatemala, CEDFOG. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.